It was 1965, the year that ran from the last half of my junior year in high school through the beginning of my senior year. In between, I spent the summer traveling through Norway and Europe. I mention that last because it made that year quite distinct in my memory, and I can recall all the books I read that year. Or all I can remember; there may be a few I’ve forgotten.

It was a year of promiscuous reading. I picked up most anything. I have a list of them. I couldn’t get enough. Schoolwork suffered because I was largely bored by my classes, other than my English classes. I rebelled against doing homework — nothing worse than the questions at the end of a chapter, a tedious exercise. But reading on my own, outside curriculum, held me rapt.

That year marked a change in the direction of my reading. When I was younger, I buried myself in non-fiction. One subject after another would overtake me and I would immerse myself in it. When I was in the eighth grade, my mother got me a young-adult novel, thinking I would enjoy it. But I didn’t read fiction. I remember I told her, “I don’t want to read anything that isn’t true.” But history, biography, essays — even cookbooks — they were “true.” They wouldn’t clog my head with fictional effluvia.

For some reason, that changed in 1965. I picked up novel after novel. Not those assigned in school, of course. That was dry, tired, musty old fustian. I wanted to read what was current, new, on the biting edge. There was James Purdy, John Updike, Hubert Selby Jr., Thomas Pynchon. Needless to say, all of them were well above my meager level of understanding as a 16-year-old.

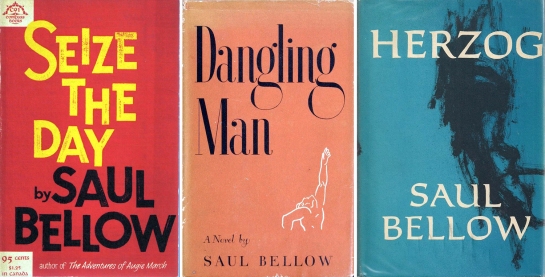

Some of the reading came in clumps. I read Saul Bellow’s Herzog when it came out, and followed that with Seize the Day and Dangling Man. To let you know how little I understood what I was reading, I reread Herzog earlier this year and was surprised — pleasantly — to discover it is a comedy. A very funny book. I’m afraid the thick layer of irony that makes the book such a delight was invisible to my adolescent mind. I think I saw it the first time as a window on the academic life I was planning to lead after I got out of college, after I got into college.

I had a Kerouac streak, soaking up first Big Sur then Dharma Bums. When I was in Oslo, I found a British paperback of Lonesome Traveler, a series of essays. For a kid my age, this was catnip. When I got home, I finished off On the Road — which I have managed to reread every decade or so, the last time in its original scroll version with all the names undisguised. No, it doesn’t hold up, but what an effect it had on me as a wimpy pimply-faced kid.

I had a Kerouac streak, soaking up first Big Sur then Dharma Bums. When I was in Oslo, I found a British paperback of Lonesome Traveler, a series of essays. For a kid my age, this was catnip. When I got home, I finished off On the Road — which I have managed to reread every decade or so, the last time in its original scroll version with all the names undisguised. No, it doesn’t hold up, but what an effect it had on me as a wimpy pimply-faced kid.

The series I probably read the most of was Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu. I ate them through like Mars bars. I can’t remember most of their actual titles, they were all sequels like “son of,” and “daughter of” or “return of,” and the plots were interchangeable, but I loved the adventure and the atmosphere of London’s Limehouse district, with its opium dens and insidious “Yellow Peril.” The racism of the books was not yet apparent to me, and when I tried rereading one of them a few years ago, I couldn’t wade through the Victorian-style prose.

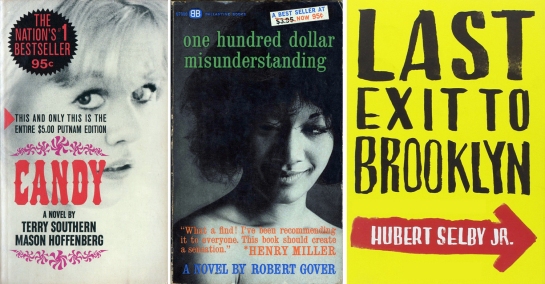

A few appealed to my burgeoning hormones and growing anti-bourgeois prejudices. Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg’s Candy was hot stuff to a teenager and so was Robert Gover’s One Hundred Dollar Misunderstanding. Hubert Selby Jr.’s Last Exit from Brooklyn was another one way above my pay grade in understanding, but I knew it was subversive.

A few appealed to my burgeoning hormones and growing anti-bourgeois prejudices. Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg’s Candy was hot stuff to a teenager and so was Robert Gover’s One Hundred Dollar Misunderstanding. Hubert Selby Jr.’s Last Exit from Brooklyn was another one way above my pay grade in understanding, but I knew it was subversive.

(In the same vein, among my other reading were two periodicals. I subscribed to both the Evergreen Review and Paul Krassner’s The Realist. Couldn’t wait for the next Phoebe Zeit-Geist. Such things were puerile, but then, I was a puer. A couple of years later, I was publishing a sophomoric underground newspaper at my college, called the K.M.R.I.A Journal. But then, I was a sophomore.)

There was literary fiction I read, beyond Saul Bellow. I tackled Thomas Pynchon’s V., although I have no recollection of what I might have made of it back then, but I knew the character names were clever. There was Louis Auchincloss and Walker Percy.

Not all of it was high-minded. In Norway, I found a copy of Pat Frank’s Mr. Adam, a post-apocalyptic lampoon, and Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim. At that age, I also thought John Lennon was not only clever, but profound. At that age.

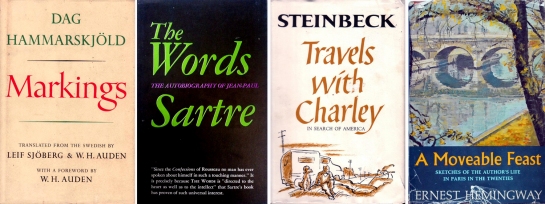

There were memoirs by Jean-Paul Sartre and Ernest Hemingway, and social and philosophic essays by Marshall McLuhan and Eric Hoffer. And something in-between: Dag Hammarskjöld’s Markings.

The film, Zorba the Greek, came out the year before, and so I picked up the book. It launched me into a series of books about Buddhism (Alan Watts, Christmas Humphreys, D.T. Suzuki) which kept me going in the spring of 1966. But it also dumped me deep into Kazantzakis’s The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, which I read in my stateroom on my transatlantic shipboard trip to Norway. There was a lot of time to kill and a very fat book to murder it with.

I imagine my teenage years were peculiar. I came from a quiet middle-class family. I doubt there were as many as a dozen books in the house, outside the grocery-store-premium Funk & Wagnalls. We lived on the New Jersey side of The Bridge (GW, that is — George Washington) and I spent as much time as I could on the non-Jersey side of that bridge, visiting art museums, concert halls and bookstores. In particular, I took the subway down to the Sheridan Square Paperback Corner, a tiny, crowded store with books piled high on all walls. (There was also the Hudson News at the 178th Street bus terminal, where I stopped every time before getting on the Public Service bus to go home to the benighted other side of the Hudson River.)

There was a time, many years later, when I was unemployed and nearly homeless (praise be to dear friends), that I dove back into the books and for a period of six months or so, read a book a day. I cannot say that such speed-reading provided the same depth of experience, but I soaked up a great deal that has served me well in the 40 years since. Reading has been my life, and has come out the other end as writing.

I suppose I mention all this Proustian self-absorption because I look around the house now that I have turned 71 and see my walls held up by floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, and know that a lifetime of constant reading began in those years that — at the time — I considered a complete waste. High school was a torture I absolutely hated. Books taught me a billion times more than those classrooms ever did. It must say something that I remember so many of the books I read in that one seminal year. And have reread so many of them as a grown-up.

These are the covers of the editions I read in 1965, click on any image to enlarge