I love long sentences. I’m tired of all the short ones. Hemingway can keep them. Newspapers can urge them. Twitter can mandate them. To hell with them.

My ideal can be found in the long serpentine railways of words shunted hither and thither over dependent clauses, parenthetical remarks, explanatory discursions and descriptive ambiguities; sentences such as those found in the word-rich 18th century publishing world of Fielding, Sterne, Addison, Steele, or Boswell, and perhaps most gratifyingly in the grand, gravid, orotund sentences of Edward Gibbon, whose work I turn to not so much for information about the grandeur that was Rome, but for the pure sensuous pleasure to be had from those accretive tunes built from the pile of ideas and imagery (to say nothing of ironic asides), and peppered liberally with the notations of colons, semicolons, dashes and inverted commas.

Needless to say, my love of such sentences caused me some embarrassment during my years as a practicing journalist, where I was encouraged to keep my sentences simple and clear. I am sure I must have tested the patience of many an editor over those years. I did pick up one countervailing habit: My paragraphs tend to be short. Often a single sentence per.

Needless to say, my love of such sentences caused me some embarrassment during my years as a practicing journalist, where I was encouraged to keep my sentences simple and clear. I am sure I must have tested the patience of many an editor over those years. I did pick up one countervailing habit: My paragraphs tend to be short. Often a single sentence per.

It is not only 18th century writing I enjoy. The same love of the trailing, dawdling sentence gives me pleasure in William Faulkner, James Agee and Lawrence Durrell. I want to settle into each sentence as if it were a good book.

I remember in the second or third grade learning to diagram sentences. Noun, verb, object; subject, predicate. This was the armature upon which was built increasingly baroque structures. (When we had assignments to use our newly learned vocabulary words in sentences, I always tried my best to use the entire list in a single sentence.)

What kind of sentence am I talking about? When Gibbon talks ironically about how the spiritual “gifts” of early Christians as well feathered their own nests as proved their piety, he follows with: “Besides the occasional prodigies, which might sometimes be effected by the immediate interposition of the deity when he suspended the laws of nature for the service of religion, the Christian church, from the time of the apostles and their first disciples, has claimed an uninterrupted succession of miraculous powers, the gift of tongues, of vision, and of prophecy, the power of expelling daemons, of healing the sick and of raising the dead.” I like that: “suspending the laws of nature for the service of religion.” Gibbon has a way of making clear his own skepticism through irony while at the same time never crossing the line into a simple “Nya-nya.” It is a performance of extreme delicacy.

Tristram Shandy lays the (comic) misfortune of his life to the interrupted coitus of his conception, explaining in one grand run-on sentence: “Believe me, good folks, this is not so inconsiderable a thing as many of you may think it; — you have all, I dare say, heard of the animal spirits, as how they are transfused from father to son, etc., etc. — and a great deal to that purpose: — Well, you may take my word, that nine parts in ten of a man’s sense or his nonsense, his successes and miscarriages in this world, depend upon their motions and activity, and the different tracts and trains you put them into, so that when they are once set a-going, whether right or wrong, ’tis not a half penny matter, — away they go cluttering like hey-go mad; and by treading the same steps over and over again, they presently make a road of it, as plain and as smooth as a garden-walk, which, when they are once used to it, the Devil himself sometimes shall not be able to drive them off it.”

The extreme pleasure of the book is as much linguistic as it narrative.

Or from The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling: “For the reasons mentioned in the preceding chapter, and from some other matrimonial concessions, well known to most husbands, and which, like the secrets of freemasonry, should be divulged to none who are not members of that honourable fraternity, Mrs. Partridge was pretty well satisfied that she had condemned her husband without cause, and endeavored by acts of kindness to make him amends for her false suspicion.”

Simple thoughts may be satisfied with simple sentences, but knotty thoughts, thoughts of subtlety and complexity, require longer compound and compound-complex sentences; sentences in which ideas are parsed, turned over, elucidated, tested and rubbed up against themselves.

(I am reminded that in The Bear, a portion of Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses, a single sentence continues for 11 pages. To say nothing of Molly Bloom’s soliloquy. Hurrah.)

These sentences I admire and enjoy, are not mere coagulations of verbiage, but rather like puzzle pieces that fit together ultimately to make a perfect construction. Or the worms and gears of an intricate machine turning smoothly. They might be compared to their advantage to the miserable word salad of unfinished thoughts and undefined terms of the blather of Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump: long empty strings of cliches and bigotry, and cliched bigotry, in a never-ending stream of inanities and incoherencies that never reach that concluding peroration that brings all the eggs into a single meaningful basket. It is language spewed, not built. My heroes learned their lessons from the classical languages, whence Aeschylus can have his opening speaker in The Agamemnon go on for a full page before punctuating his speech with the single concluding verb that ties the whole performance up in a word that makes sense of all that came before. Grammar can be used to effect: Trump hardly knows there is such a thing as grammar. He is a bilge pump.

But all this is only prolog to my actual subject for today: The odd and magical concatenation of entries, definitions, etymologies and examples found in the famous dictionary of Dr. Johnson. Johnson has his many prejudices that today strike the reader as comical, as when he defines “oats” as “A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.” Or defines “stateswoman” as: “A woman who meddles with publick affairs. In contempt.”

Nevertheless, if you consider the immensity of the task he set himself in 1746 — a task that wound up taking away nine years of his life — you must admire his profound sincerity and deep devotion. He put together the first comprehensive English dictionary, and in doing so, pretty well had to come up with the plan for it ab ovum. (There were glossaries and word lists, and a few dictionaries before him, but none complete or even attempting to be so). If his definitions sometime seem a trifle punctilious, it must be remembered he was pretty much inventing the whole idea. The definitions range from those that hardly convey what we would consider sufficient information (“Rhinoceros: A vast beast of the East Indies armed with a horn on his front”) to those that seem to do verbal somersaults to convey their meaning (“Network: Anything reticulated or decussated, at equal distances, with interstices between the intersections.” By the way: “To Decussate: To intersect at acute angles” and: “Reticulated: Made of network; formed with interstitial vacuities.”)

Nevertheless, if you consider the immensity of the task he set himself in 1746 — a task that wound up taking away nine years of his life — you must admire his profound sincerity and deep devotion. He put together the first comprehensive English dictionary, and in doing so, pretty well had to come up with the plan for it ab ovum. (There were glossaries and word lists, and a few dictionaries before him, but none complete or even attempting to be so). If his definitions sometime seem a trifle punctilious, it must be remembered he was pretty much inventing the whole idea. The definitions range from those that hardly convey what we would consider sufficient information (“Rhinoceros: A vast beast of the East Indies armed with a horn on his front”) to those that seem to do verbal somersaults to convey their meaning (“Network: Anything reticulated or decussated, at equal distances, with interstices between the intersections.” By the way: “To Decussate: To intersect at acute angles” and: “Reticulated: Made of network; formed with interstitial vacuities.”)

We are so used to a more casual and informal speech these days, that it is a pleasure to see these words in their after-five formal dress. (“Rosin: Inspissated turpentine; a juice of the pine.”) Remember, Johnson had to invent his definitions from sheer air. How would you do if you were faced with defining several thousand words from scratch? How would you define “lard,” for instance. For Johnson, it was “the grease of swine.” There is both an elegance to that terse explanation, but also, to our ears, a kind of humor. We don’t speak that way anymore.

Or how would you explain “smoke?” Johnson: “ The visible effluvium, or sooty exhalation from anything burning.” “Sun?” “The luminary that makes the day.”

Den? “A cavern or hollow running horizontally, or with a small obliquity, under ground; distinct from a hole, which runs down perpendicularly.” The nicety of the distinction is deeply felt for someone who cares about language.

“Mouth: The aperture in the head of any animal at which the food is received.”

“Tree: A large vegetable rising, with one woody stem, to a considerable height.”

“Wolf: A kind of wild dog that devours sheep.”

“Orgasm: Sudden vehemence.”

Can you do better? Well, in some cases, yes, but only because we have several hundred years worth of lexicography behind us (and less delicacy about sex). Remember, Johnson was inventing the thing, a first draft.

I like it when the language is wearing its white tie and waistcoat: “Cough: A convulsion of the lungs, vellicated by some sharp serosity. it is pronounced coff.” If you flip the pages, you find also: “To Vellicate: To twitch; to pluck; to act by stimulation.”

Or: “Whey: The thin or serous part of milk, from which the oleose or grumous part is separated.”

Some of the definitions bear the wisdom of Johnson’s worldview, giving us more than we may actually need to know: “Compliment: An act, or expression of civility, usually understood to include some hypocrisy, and to mean less than it declares.”

There are many words that no longer survive in any meaningful form: “Stirious: Resembling icicles.” And there are words where Johnson threw up his hands: “Stammel: Of this word, I know not the meaning.” (OED says, “A coarse woolen cloth,” and “a shade of red in which the cloth was commonly dyed”).

There are moments where the lexicographer simply got things wrong, or took a metaphorical use as a second definition. He defined “pastern” as “the knee of a horse.” It is rather, part of the foot of a horse. When a woman asked Johnson how he came to make such a mistake, he answered, “Ignorance, Madam, pure ignorance.”

But by and large, his work was an admirable thing, for which I thank him. And thank him for the pleasure I gain both from his formality, his erudition, and the not infrequent (and often unintended) humor. It is impossible to read through the dictionary and not sense the very particular and idiosyncratic man behind it. Most dictionaries feel distant, academic, objective. Not Johnson’s book: Who read it, hears the blood and bones behind it. Everything in it — and especially its preface — its intensely personal. Its triumphs and its failings are human and profoundly so.

This shows nowhere more than in his botany and zoology. There were many animals with which he clearly had no first-hand information. Some of these were merely legendary, and often a skepticism of such hippogryphs comes out in his entry. Sometimes not.

“Alligator: The crocodile. This name is chiefly used for the crocodile of America, between which, and that that of Africa, naturalists have laid down this difference, that one moves the upper and the other the lower jaw; but this is now known to be chimerical, the lower jaw being equally moved by both.”

“Alligator: The crocodile. This name is chiefly used for the crocodile of America, between which, and that that of Africa, naturalists have laid down this difference, that one moves the upper and the other the lower jaw; but this is now known to be chimerical, the lower jaw being equally moved by both.”

“Salamander: An animal supposed to live in the fire, and imagined to be very poisonous. Ambrose Parey has a picture of the salamander, with a receipt for her bite; but there is no such creature, the name being now given to a poor harmless insect.”

“Tarantula: An insect whose bite is only cured by musick.”

“Camelopard: An Abyssinian animal, taller than an elephant, but not so thick. He is so named because he has a neck and head like a camel; he is spotted like a pard, but his spots are white upon a red ground. The Italians call him giaraffa.”

“Camelopard: An Abyssinian animal, taller than an elephant, but not so thick. He is so named because he has a neck and head like a camel; he is spotted like a pard, but his spots are white upon a red ground. The Italians call him giaraffa.”

It is fun to read through the dictionary as a kind of bizarro-world view of 18th century natural science, punctuated by Johnson’s peculiar phraseology and word choice: “Tadpole: A young shapeless frog or toad, consisting only of a body and a tail; a porwiggle.” As for the tail: “That which terminates the animal behind; the continuation of the vertebrae of the back hanging loose behind.”

I wish I could go on with so many more entries, but I can only end with a few.

“Starfish: A fish branching out into several points.”

“Starfish: A fish branching out into several points.”

“Frog: A small animal with four feet, living both by land and water, and placed by naturalists among mixed animals, as partaking of beast and fish. There is likewise a small green frog that perches on trees, said to be venomous.”

“Toad: An animal resembling a frog; but the frog leaps, the toad crawls: the toad is accounted venomous, I believe truly.”

“Wasp: A brisk stinging insect, in form resembling a bee.”

“Serpent: An animal that moves by undulation without legs. They are often venomous. They are divided into two kinds; the viper, which brings young, and the snake, that lays eggs.”

“Lizard: An animal resembling a serpent, with legs added to it.”

“Shrewmouse: A mouse of which the bite is generally supposed venomous, and to which vulgar tradition assigns such malignity, that she is said to lame the foot over which she runs. I am informed that all these reports are calumnious, and that her feet and teeth are equally harmless with the mouse. Our ancestors however looked on her with such terrour, that they are supposed to have given her name to a scolding woman, whom for her venom they call a shrew.” (vide: “Shrew: A peevish, malignant, clamorous, spiteful, vexatious, turbulent woman.”)

“Elephant: The largest of all quadrupeds, of whose sagacity, faithfulness, prudence , and even understanding, may surprising relations are given. This animal is not carnivorous, but feeds on hay, herbs and all sorts of pulse; and it is said to be extremely long lifed. It is naturally very gentle; but when enraged, no creature is more terrible. He is supplied with a trunk, or long hollow cartilage, like a large trumpet, which hangs between his teeth, and serves him for hands: by one blow with his trunk he will kill a camel or a horse, and will raise a prodigious weight with it. His teeth are the ivory so well known in Europe, some of which have been seen as large as a man’s thigh, and a fathom in length. Wild elephants are taken with the help of a female ready for the male: she is confined to a narrow place, round which pits are dug; and these being covered with a little earth scattered over hurdles, the male elephants easily fall into the snare. In copulation the female receives the male lying upon her back; and such is his pudicity, that he never covers the female so long as anyone appears in sight.”

“Elephant: The largest of all quadrupeds, of whose sagacity, faithfulness, prudence , and even understanding, may surprising relations are given. This animal is not carnivorous, but feeds on hay, herbs and all sorts of pulse; and it is said to be extremely long lifed. It is naturally very gentle; but when enraged, no creature is more terrible. He is supplied with a trunk, or long hollow cartilage, like a large trumpet, which hangs between his teeth, and serves him for hands: by one blow with his trunk he will kill a camel or a horse, and will raise a prodigious weight with it. His teeth are the ivory so well known in Europe, some of which have been seen as large as a man’s thigh, and a fathom in length. Wild elephants are taken with the help of a female ready for the male: she is confined to a narrow place, round which pits are dug; and these being covered with a little earth scattered over hurdles, the male elephants easily fall into the snare. In copulation the female receives the male lying upon her back; and such is his pudicity, that he never covers the female so long as anyone appears in sight.”

And the elephant also brings us back to the GOP and its excrescences: “Trumpery: Something fallaciously splendid; something of less value than it seems.”

As Minor White said of the Weston photographs: “Rarely are we shown the maturest work of men who have lived richly and whose spirit has grown all their lives … the last photographs of Edward Weston made at Point Lobos … may parallel in content the last quartets of Beethoven.”

As Minor White said of the Weston photographs: “Rarely are we shown the maturest work of men who have lived richly and whose spirit has grown all their lives … the last photographs of Edward Weston made at Point Lobos … may parallel in content the last quartets of Beethoven.”

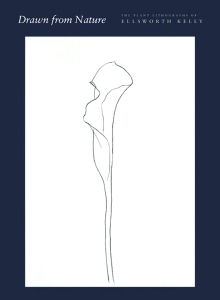

I was struck seeing some drawings by Ellsworth Kelly, who made his career with minimalist Color Field paintings — they might as well have been models for flags — but these drawings were of plants, in simple black line on simple white paper. They were elegant and expressive and nothing like the bland paintings. He has made them throughout his career, but they had been seen only once (in 1970) before they made a big splash, showing them in 2012 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Kelly clearly loved the plant forms he drew.

I was struck seeing some drawings by Ellsworth Kelly, who made his career with minimalist Color Field paintings — they might as well have been models for flags — but these drawings were of plants, in simple black line on simple white paper. They were elegant and expressive and nothing like the bland paintings. He has made them throughout his career, but they had been seen only once (in 1970) before they made a big splash, showing them in 2012 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Kelly clearly loved the plant forms he drew.