Lion-tail macaques, Woodland Park Zoo, Seattle

Woodland Park Zoo, Seattle 1978

When I finally got a job, it was at the zoo. I was hired as a peon to sell popcorn. A week later, I had been promoted to manager and had the safe combination. The concessions stand at the zoo became my little kingdom; I ran it just as I wanted to. I hired the people I wanted and ignored company regulations when they seemed stupid. As a result, our zoo business made money even when the tourist season was over and all the other “restaurants” in the company were losing money down at the Puget Sound docks.

I worked in an iron box maybe 11 feet by six feet deep surrounded by Rube Goldberg steaming, fuming machines.

The concessions stand is a trailer, like those seen at little league games of county fairs, and at lunchtime, the lines for wieners and Pepsi stretch around the children’s zoo. I felt like some zoo animal myself, people staring as they walked past at this six-foot simian with a white snapper cap and striped vest smiling through his beard. But the real zoo was outside my steel cage:

“What do you have to drink?”

“Pepsi, 7-Up, Orange, Diet Pepsi and milk.”

“No grape?”

“No grape.”

“I’ll have root beer, then.”

One woman whose root beer thirst couldn’t be satisfied elsewise asked my to mix half orange and half Pepsi. (I tried it after she left to see if it was as vile as it sounds and it is.)

“You have peanuts?”

“No peanuts. We have popcorn.”

“I never heard of a zoo without peanuts. What do we feed the animals?”

(Under my breath: “That’s WHY we don’t have the damn peanuts, idiot.”)

One sweet motherly woman took us for an information booth and asked, “Do they mate the gorillas every day?”

“I think they pretty much let the gorillas do what they want.”

Early on one day, a young woman in a zookeepers uniform wandered by carrying a baby gorilla like a two-year-old in her arms. He must have weighed nearly 100 pounds. Around lunchtime, an elephant walked past, guided by two men who had to whip his trunk to prevent him from turning at us and snaffling popcorn. In the afternoon, the gorilla woman went by in the other direction with the gorilla twitching one hand on her breasts.

Bobo all grown up

We sold only a few items. There were the aforementioned drinks, hot dogs, potato chips, popcorn, coffee, crackerjacks, Cheez-twirlz and an abominable nougat candy called Big Hunk. It was our only candy bar and no one seemed to want it, and considering the crap that they were willing to eat, that was surprising.

“What kind of candy you got?”

“Big Hunk,” I said, grinning and holding out a bar.

“Izatall? No thanks.”

And considering what we sold, I was amazed at the naivete of another with-it mother, who asked, “Do your hot dogs have any nitrates? We don’t want any nitrates.”

“Nitrates? I don’t know, but there are some mighty tasty fly legs, and if you look close, you can see the coagulated sputum.”

She also asked if the orange pop was carbonated, apparently wanting to protect her urchin from carbonic acid. She settled on a bag of barbecue potato chips “with no preservatives.”

The hot dogs were made of turkey and spices and anything else, and they sat all day bloating in a steel box of simmering water. When I picked up the little suckers with the tongs, they sometimes disintegrated. But they were better than the buns.

The buns sat in a steamer that hissed and sputtered all day, acting like some volcanic fumerole. If they remained too long, they turned into a finger of wallpaper paste and were as appetizing as jellied snot.

And with the bun steamer blasting, the pup steamer simmering, the coffee machine blustering and the tea pot heating that little trailer was one large Vicks Vaporizer. Steam condensed everywhere and the bottoms of all the shelves dripped, leaving the floor eternally sopping. I enjoyed that. I enjoyed the infernal, brimstone appearance of all that venting steam. At least I enjoyed it the first day.

Meanwhile, I just had to enjoy watching people like the couple who walked toward us from the children’s zoo talking about how cute all the loose animals were. There were peacocks, guinea fowl, mallards, cocks and hens. Then a squirrel jumped out of the bushes and ran right up to the woman stopping just short of hopping on her leg. They stood there, startled, not knowing what to expect. The squirrel twitched his nose suddenly and the wife jumped behind her hubby, screaming and he, no John Wayne, couldn’t think of anything to do. The squirrel had made his point, and feeling reasonably superior, he dived back into the geraniums, looking for another victim.

And yes, I got to eat hot dogs free for lunch.

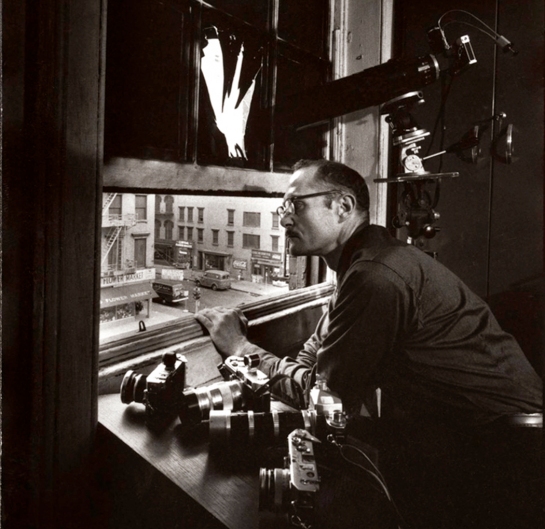

Woodland Park and Green Lake, 4 decades ago

Of course, the zoo had its share of misfits, people who may well have belonged on the other side of the bars.

There was Bill Cowell, the old relief keeper. He had seniority and could vary his routine, taking care of whatever animals needed help while their regular keeper was sick or on vacation. Bill was getting on and had lost some of his former sharpness, but he still talked over the speed limit.

One day, he brought in a newspaper story about Johnny Weismuller, ex-Tarzan and faded Olympic star. Johnny was in a sanitarium and apparently senile, running through the halls, scaring the other geriatrics with his Tarzan yells. Bill brought out this piece of paper clipped from the Post-Intelligencer and started telling me, “You are too young to remember this guy, but maybe you’ve read about him. Johnny Weismuller, he used to swim in the Olympics. You ever heard of him?”

“Yeah,” I said. “He was Tarzan.”

“Uh-huh. He starred with, uh, Muriel O’Sullivan, I think it was. But you’re too young to know those movies.”

“I saw them all on television.”

“Oh, yeah. I guess they have been on TV. Well, read this. It’s real sad. I guess I’m next. But I really think someone’s trying to make him look crazy to get at his money, you know, like they did with Groucho Marx. I bet he ain’t crazy at all.”

Another time, he endeared himself to me when, on a busy Saturday, with crowds of kids screaming and spilling their popcorn and crying and parents at the end of their patience, he said, as he bought his daily hot dog, “These goddamn kids — Dont’cha just wanna run them over?”

As in any retail business, whether it’s a tavern or a hot dog stand, you got to know regular customers by their orders. One regular was Large Pepsi No Ice. He was on the maintenance crew and picked up the mess we caused by handing kids all the paper wrappings they loved to strew across the grounds. LPNI was about 50 with a permanent 5-O’clock shadow and a view of the world honed on his dedication to professional wrestling. He was married but professed to hate his wife, saying so in a tone of voice I understood to be the tenderest expression he was capable of. Or the next tenderest: I remember him saying as he took a break to go over and watch the orangutans, “I’ve got to go see my babies today.”

He loved sports and Seattle was a good city for it. He brought me all the news everyday of his beloved Sonics. He also kept up with the Mariners and Seahawks. He had tickets to the last playoff game between the Sonics and the Lakers, but was torn between going to watch the roundball and watching his favorite wrestler at the Arena. he had tickets to both and finally decided to watch Nasty McGurdle fight Big Anastasio for a while (“There should be lots of blood flowing tonight”) and then move over to the Coliseum to catch the last half of the Sonics game.

We talked about how good it was that the Sonics got rid of Marvin Webster and then how Bob McAdoo was hurting the Celtics by being a one-man team. LPNI Liked McAdoo a lot, however. He explained himself: “McAdoo is like me; I’m a great pig fucker.”

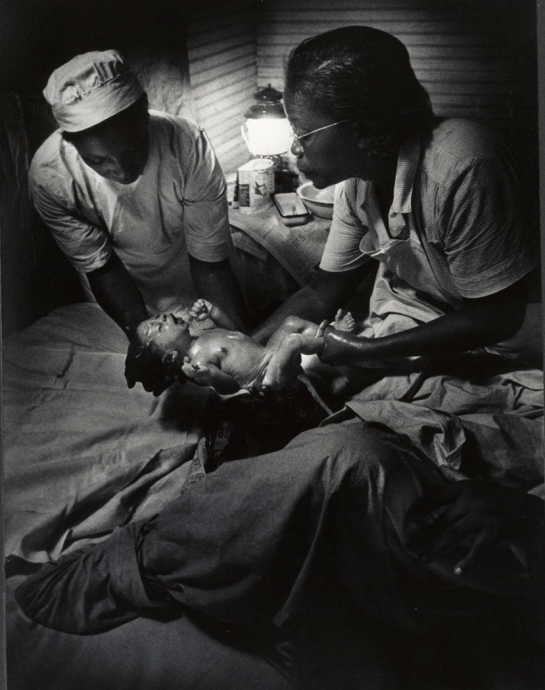

Then there was Eugene. He was also maintenance. He was about 60 and black. He talked about when he used to live in Oakland, but I could tell by his rural accent that he used to live on a farm somewhere before Oakland.

“Yes, yes. I comes from Arkansas.”

He drank five or six cups of coffee a day, paying for maybe two of them. (“How about a heatin’ up for this cup?”)

“I don’ believe in doin’ no work. I never worked in Oakland. I jus’ hustled the streets. Made a good livin’ at it, too. But when I gets to Seattle, I finds a good woman and she makes me get this here job. I don’ mind it much, I guess. It ain’t hard. But this rheumatiz in my neck is gettin’ me. I got to go see a doctor ’bout it. I thinks the bones in my neck is grinding themselves and the marrow is comin’ out, like you see on a hog when the bone is wearin’ and busted. You ever see the marrow of a hog’s bone?”

And to anyone who hangs around them, the people working at the zoo are often just as exotic as the slow loris or Przewalski’s Wild Horse. There is the twitch-eyed monkey keeper who looks like his lion-tailed macaques, the avuncular bear keeper who likes to pitch day-old hot dogs down the bottomless maw of his grizzlies, the tropical-house keeper who has to dig down the throat of a questionably sedated crocodile to pull out the gobs of ingested pennies heedless zoogoers have tossed into his water.

But the oddest zookeeper of all is the night-keeper, who skulks around the grounds in the dark with his flashlight and walkie-talkie.

I met one one evening just before closing time. We were both leaning over the rail in front of the orangutans.

“Fascinating, aren’t they?,” I asked.

“Oh, hell, they ain’t too fascinating,” he answered in a growling voice of a 50-ish blue-collar man who knows what it is to be an alpha male.

I said I thought he must have been a zookeeper too long, if the animals had lost their appeal.

“Well, I used to think they were fascinating,” he said, “but then I got to know them pretty close. They are stupid.

“As far as evolution goes, the orangs are just hanging on. They aren’t adapted well. They need a specialized habitat and it’s disappearing.”

A staccato of static blasted from his intercom and he answered something back, then stuck it back in the leather holster on his belt.

Towan

“Now, I’ve known some pretty smart gorillas, and a lot of mediocre ones, and a few dumb gorillas. And the chimpanzees — I’ve known a whole lot of really smart chimps. There are some stupid chimps, too, but not many. But I’ve never known a smart orang.

“Once, when I was in Sumatra, I was walking out in the brush and this huge male orang came walking up to near where I was. He came to maybe 10 feet from me and I stood stock still so I wouldn’t disturb him. I thought he knew I was there, but wasn’t going to give an inch of his territory. He was the biggest orang I ever saw and he was standing around digging up grasses and roots. He finally walked on without so much as acknowledging my presence.

“That was the start of my fascination with orangs. It wasn’t until years later that I found out the ape got that close to me only because he was too dumb to know what I was and what a threat mankind posed for him.”

“You seem to like the apes,” I said. “Do you know why this zoo doesn’t have any chimpanzees?”

“Well, a few years ago, a political decision was made somewhere in the front office that we didn’t have enough money to support all three great apes, so they decided to get rid of the chimps. It’s always politics that runs things, never what the zoo needs or how we can solve a problem.

“Someone in the administration, who probably had never even been to the zoo, decided to get rid of the chimps. It’s like the new displays that are being built.”

Towan, the male orang in the cage, looked through the glass and offered us some chime from his outstretched lower lip. It’s an orang’s way of saying, “grab a seat, make yourself at home.”

We talked about the new gorilla exhibit, one of those open-ground enclosures that replaced the dingy old glass-front cages that used to be used.

“It’s all political,” the zookeeper said, with some bite in his tone. “These people think it will be better for the gorillas to be out in a more ‘natural habitat.’ But, hell, our gorillas were born in captivity. They’ve never known what it is to be out in the open. We don’t know what will happen; chances are, the gorillas will be freaked out by the change. We introduce stressors in their life, saying it will reduce them. But it is only our own conscience that is calmed. Five of our gorillas were born in captivity. For them the cage is the natural habitat. I’m sure the stress will kill at least one of them. But I was never asked. Someone up front decided it was politically better to give them trees and concrete mountains. At least one will die.

“I guess I’ve been around and I know about as much about departing as anyone on this earth and I know that you don’t die without giving up. That goes for apes and humans, too. No one ever died without giving up somehow. Even a wreck on the freeway means that someone gave up.

“Disease is just partial suicide. You give up part of your will to live and you get sick. The human body was designed to fight off disease. But when you give up, you let the germs and microbes into your system. I haven’t had so much as a cold in seven years. Not that I don’t take care of my body. I eat good foods and keep myself in shape. But I haven’t seen a doctor in a long time and I intend to keep it that way. Doctors are like mechanics. You keep your car healthy and you don’t need one. But if you have a wreck or it breaks down, the mechanic can fix it, but it’s never as good as it once was.

“People get sick because their will is worn down by stressors. Just like the apes will be worn by moving them; they can’t take the stressors.”

Towan tilted his red-haired simian head and began playing peek-a-boo with the remains of the burlap sack he is given daily.

“Like the IRS,” the nightkeeper went on. “Every year they take a little more out of your pay and they figure out some new way to make life harder.

“I wonder if the federal government knows how much disease it causes by not living within its budget.

“It’s not the money they take out. We can afford to pay it, but every year they take a little more and each increase is a stressor and someone gets sick, maybe dies because of the federal government. It’s all politics.”

And somewhere in the increasing dusk, a peacock screeched and it was time to close.

Towan reached his long arms side to side and embraced the glass. Then he climbed up the steel posts that made for trees in his cage and he sat in his roost next to Melati, one of the females.

Sleep well, Towan, I thought. Life could be worse. You could have to file a 1040.