I’ve been to the Louvre in Paris a number of times, but no matter how long I spend there, I never feel as if I’ve seen more than two percent of it. It is vast. It is the largest museum in the world, with 782,910 square feet of floor space (topping the No. 2 museum, St. Petersburg’s Hermitage, by more than 60,000 sq. feet) and a collection of more than 600,000 pieces.

It’s where you go to find the Mona Lisa, the Winged Victory of Samothrace and the Venus de Milo.

It’s one of the oldest museums around, but never seems quite finished. It began as a royal palace in the 12th century, and has been added on to, parts burned down, parts replaced, and even a glass pyramid added to the top.

When Louis XIV moved the court from the Louvre to Versailles in 1682, the building became a warehouse for kingly treasures and much of his art collection. in 1699, the first “open house,” or salon was held, and for a century, the royal academy of art was located there.

The French Revolution ended the monarchy, and all the art once owned by the king became public property, and in 1793, the new government decreed that the Louvre should be open to the citizens as a free art museum.

But soon after, the collection expanded exponentially, as Napoleon Bonaparte conquered half of the continent, and sent back to Paris a good deal of the art from conquered lands. He even had the museum renamed Musée Napoléon. That didn’t last, but neither did Napoleon.

Over the 19th century, the museum collection grew, from bequests, purchases and colonial expropriations. For a while, it included a whole section of Pre-Columbian art from the New World, but that spun out into its own museum, leaving the Louvre for the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in 1887; in 1945, the Louvre’s extensive collections of Asian art were moved to the Guimet Museum; and by 1986, all the museum’s art made after 1848, including Impressionist and Modernist work, was transferred to the Musée d’Orsay, a refurbished railways station. It seemed the Louvre kept bursting its seams.

Then came François Mitterrand. Serving as French president from 1981-1995, Mitterrand conjured up the Grand Project to transform the cultural profile of Paris, with additional monuments, buildings, museums, and refurbishment of existing locations. Taxes were raised to accomplish this project, said to be on a scale that only Louis XIV had attempted.

Part of this plan was the Grand Louvre, to remodel and expand the museum, and to regularize (as much as possible) the maze and warren of galleries in the old accretion of palace rooms. The most visible of the changes was the addition of the glass pyramid in the center courtyard of the palace. It was designed by architect I.M. Pei and although it has long become part of the landscape of the museum, it still angers many of the country’s more conservative grouches. In 2017, The American Institute of Architects noted that the pyramid “now rivals the Eiffel Tower as one of France’s most recognizable architectural icons.”

The entire central underground of the courtyard was remodeled to create a new entrance, and to attempt to make sense of the confusion of corridors, rooms, staircases and doorways. It was completed in 1989.

Now, one cannot think of the Louvre without its pyramid, but speaking as a visitor, while the Hall Napoléon (the underground foyer) has made some sense of the confusion, I cannot honestly claim the chaos has been tamed. The museum remains a labyrinth and you can be easily lost.

And, unless you have budgeted a month or more to spelunk the entire museum, you will need to prioritize what you want to see in a visit — or two, or three.

Quick word: Forget the Mona Lisa. It’s a tiny little painting of little artistic note, buried under a Times Square-size crowd of tourists all wanting to see the “most famous painting in the world.” It is what good PR will get you. It may be a historically noteworthy piece as one of the very few paintings Leonardo completed, but there is much better to be seen in the museum. Don’t exhaust yourself in the mêlée.

Seek out the unusual, like Jan Provost’s Sacred Allegory, from about 1490, which I like to call “God’s Bowling Ball;” or The Ascension, by Hans Memling, from the same time, which shows Christ rising into heaven, but shows only his feet dangling from the clouds. There’s some quirky stuff on the walls of the Louvre.

One of the goals of the museum is to collect, preserve, and display the cultural history of the Western world. This is our art, the stuff we have made for more than 3,000 years, from Ancient Sumer and Egypt, through classical Greece and Rome, wizzing past the Middle Ages and brightening with the Renaissance and the centuries that followed. You get the whole panoply and see what tropes have persisted, the ideas that have evolved, the stuff of our psychic landscape.

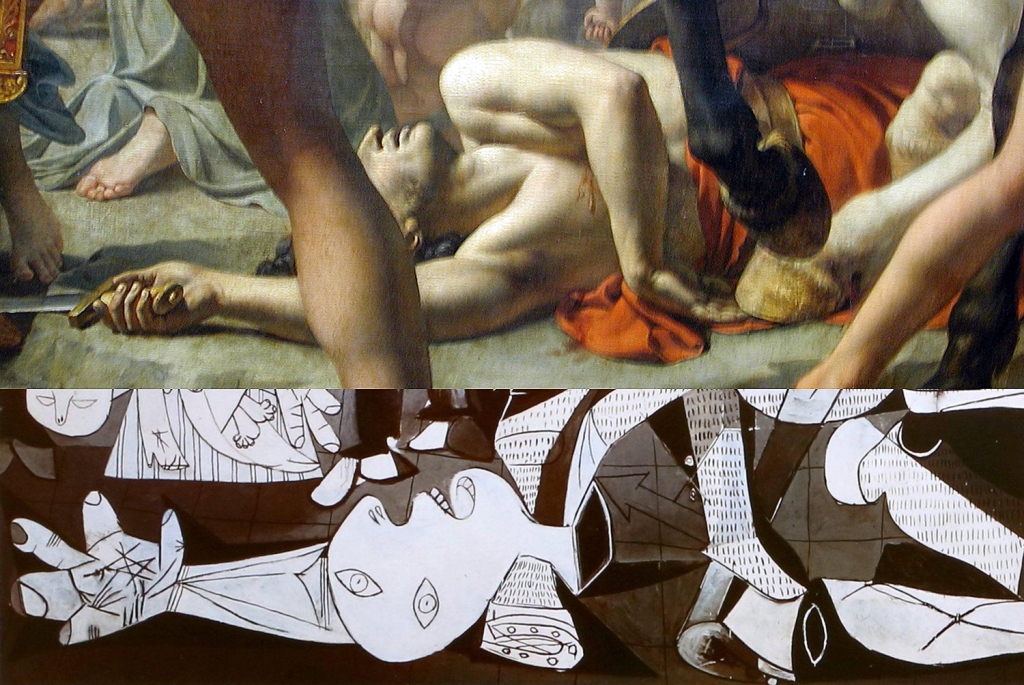

(See how the fallen soldier in Jacques-Louis David’s Intervention of the Sabine Women echoes in Picasso’s Guernica. One way of looking at all cultural history is as an extended conversation between the present and the past. The reverberations are loud and clear.)

You can look at the paintings on the wall and see them for the beauty of their colors and brushwork, or the familiar (or not-so-familiar) stories they depict; or you can see them as the physical embodiment of the collective unconscious.

I have always been a museum-goer. From my earliest times as a boy going to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, through my days as an art critic, rambling through the art museums of the U.S. and abroad. There is little I get more pleasure from.

One soaks up the visual patterns, makes connections, recognizes the habits of humankind. Recognizes the shared humanity. The differences between me and Gilgamesh are merely surface tics. When I see the hand of the Roman emperor, it is my hand. I feel kinship with all those whose works and images appear in the galleries.

And so, if it is two percent of the Louvre I have managed to absorb, I know the rest is there, and that it is me, also.

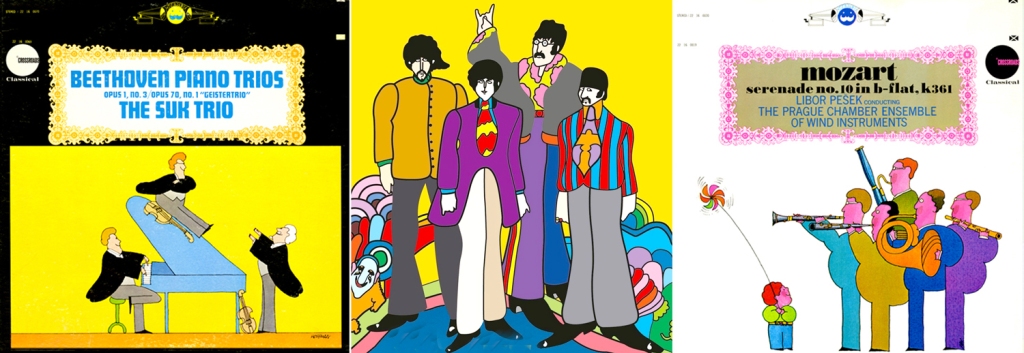

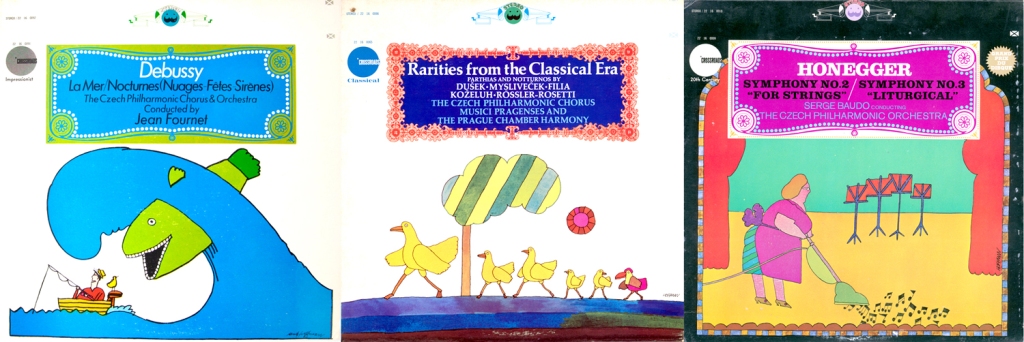

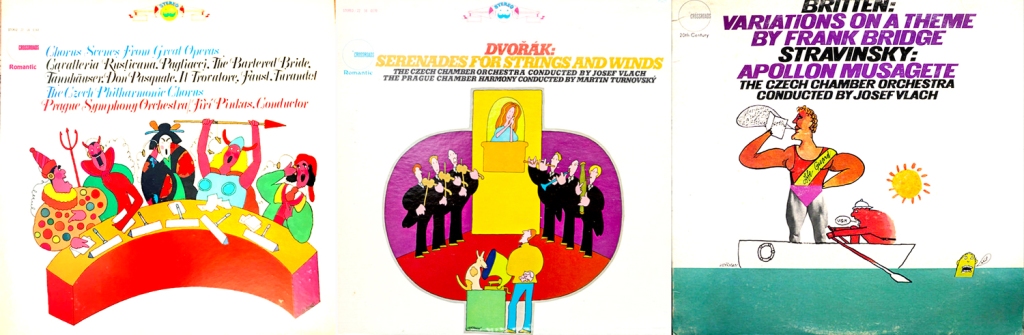

Click on any image to enlarge