“There’s no such thing as bad art.” This was a dictum of the late classical music critic Dimitri Drobatschewsky. He explained: “If it’s bad, it’s not art.” But I have to take exception. There are examples of works that are deeply flawed, yet they stick in our psyches in just the same way as a masterpiece.

To take an extreme: Ed Wood’s Plan 9 From Outer Space is often nominated as the “worst movie ever made,” yet, there are piles of other bad movies that have fallen into justified oblivion. Something about Plan 9 wheedles into our brains and lodges there, despite dialog such as, “We are all interested in the future, for that is where you and I are going to spend the rest of our lives. And remember my friend, future events such as these will affect you in the future.”

The movie is a peculiar kind of classic and draws viewers every time it is screened.

And speaking of tin-eared dialog, the 1933 King Kong is full of stuff such as, “It never fails. Some big hard-boiled egg goes goofy over a pretty face, and bingo! He cracks up and gets sappy.” And the acting is often wooden (Bruce Cabot especially; and even Robert Armstrong can’t make this dialog work) and the story line is racist in a way common to its era, but Kong is as much part of our cultural landscape as George Washington’s cherry tree or the Gettysburg Address.

There is something about these films that buries into our unconscious and lives there like a dream. There is a logic to real life, a cause and effect, but there is an alternate logic to dreams, and that is where Plan 9 or King Kong comes to life. Ordinary rules don’t apply.

There are many better-made movies that are completely forgettable. Shakespeare in Love won an Oscar, but can you remember anything about it? I can’t. But Kong is buried there, in the neurons, permanently, mythically.

Which brings us to one of the greatest movies ever made, or at least one of the most memorable. in a 2012 Sight & Sound poll of critics, Metropolis was voted as the 35th greatest film of all time, tied with Hitchcocks Psycho and just ahead of Truffaut’s 400 Blows. It also ranked 12th in the film magazine Empire’s “The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema” in 2010 and second in a list of the “100 greatest films of the Silent Era.”

It didn’t achieve such eminence through its plot or acting. The plot is silly and preposterous and the acting is often so over the top as to be laughable.

All built on a silly and sentimental bromide.

The film’s director, Fritz Lang, agreed about the moral, telling Peter Bogdanovich in an interview, “You cannot make a social-conscious picture in which you say that the intermediary between the hand and the brain is the heart. I mean, that’s a fairy tale — definitely.”

It looks like science fiction, but there’s no science in it. It could be a dystopian future, but it’s not set in any particular time. It is mostly a fever-dream of capitalism, except there are no economics in it.

Yet, the film has a power that many arguably better films simply can’t muster. Scene after scene in Metropolis bores deep into the subconscious.

Right from the opening scene, when the factory shift changes and one phalanx of exhausted workers exit the giant elevators, shuffling at half-speed, while the fresh phalanx marches, in step in the opposite direction at full speed. It is a striking bit of choreography, worthy of Pina Bausch, and a clue to how the rest of the movie will unfold.

In the next segment, we find our hero, Freder, cavorting with a bevy of nymphs in the “Eternal Gardens,” in a set that is actually unnerving.

Scene after scene is unreal but unforgettable.

While the plot is tangled and confused, the set-up is simple. The city is divided into an upper part, where the rich live in luxury, and an underground inhabited by the workers and the machines that keep the city running. A Romeo and Juliet story intervenes and so does a mad scientist, who makes a robot in the image of our Juliet. Chaos ensues.

Don’t look for it to make any sense. It doesn’t.

The film was conceived by director Lang when visiting New York City in 1924. “I looked into the streets — the glaring lights and the tall buildings — and there I conceived Metropolis,” he told an interviewer. He said that “the buildings seemed to be a vertical sail, scintillating and very light, a luxurious backdrop, suspended in the dark sky to dazzle, distract and hypnotize.”

At the time, Lang was married to novelist Thea von Harbou (who already had published more than 40 books) and they worked out a story, which she turned into a novel. Later, Lang and Harbou translated the book into a script.

Thea von Harbou and first edition hardcover (l.) and paperback (r.)

(I’ve just read the original novel and it is terrible, grossly overwritten and both silly and sentimental. And it used enough exclamation points to fill an oil tanker. Here is a sample: “Ah! The intoxication of the lights. Ecstasy of Brightness! — Ah! Thousand-limbed city, built up of blocks of light. Towers of Brilliance! Steep mountains of splendour! From the velvety sky above you showers golden rain, inexhaustibly, as into the open lap of the Danae. Ah — Metropolis! Metropolis!”)

Lang and Harbou working on script

Lang began filming Metropolis in 1926 at the Ufa studios in Berlin. It took 17 months to film, with 310 shooting days and 60 shooting nights and went over budget by 310 percent, costing 5.3 Reichsmarks (something like $23 million in today’s money) and nearly sent the studio into bankruptcy.

Brigitte Helm, who played the lead, and the robot Maria, said “the night shots lasted three weeks, and even if they did lead to the greatest dramatic moments — even if we did follow Fritz Lang’s directions as though in a trance, enthusiastic and enraptured at the same time — I can’t forget the incredible strain that they put us under. The work wasn’t easy, and the authenticity in the portrayal ended up testing our nerves now and then. For instance, it wasn’t fun at all when Grot drags me by the hair, to have me burned at the stake. Once I even fainted: during the transformation scene, Maria, as the android, is clamped in a kind of wooden armament, and because the shot took so long, I didn’t get enough air.”

Lang brought in 500 children from the poorest districts of Berlin to play the Workers’ children and had them in ice-cold water for two weeks, as the Workers’ City was flooded.

The film was a financial failure on its initial release, but has become one of the great classics of all time. Its afterlife, though, was inauspicious. The movie was first released at a length of two and a half hours. The studio then cut it down to about two hours, and in the U.S., it was hacked down further, and in 1936, Nazi objections to its supposed Communist subtext, it was reduced to 90 minutes. Since its rediscovery in the 1960s, there have been many restoration attempts, but even today, with 95 percent of the film rediscovered and re-edited, it is still short of the director’s cut.

And speaking of Nazis, Lang and Harbou divorced as her Nazi leanings became clear (she became a party member in 1933 and worked for the studio under Nazi rule during the war), and as for Lang, it was his bad luck that Joseph Goebbels and Adolf Hitler both liked the film and offered Lang the job as boss of all Nazi film production. Lang took the hint and fled Germany (by his own account, the very next day).

(An early scene in the movie shows a race in the Club of Sons in which the stadium architecture is astonishingly prescient of Albert Speer’s fascist architecture.)

So, why is this movie, with all its faults, such a memorable film? Unlike most, it doesn’t count on story to carry us through, and certainly not the acting. Rather, it burrows into our unconscious like a dream, with image after image that cannot be forgotten. One after the other, they pile on, right from that opening bit with the workers’ choreography.

The city is the kind of future the past used to project, with its biplanes circling the buildings and the elevated roadways around skyscrapers so tall, we cannot see their tops. In the center is the giant tower called the “New Babylon

Then, there is the Workers’ City, hidden below ground, with its Soviet-style faceless apartment buildings. The social structure of Lang’s Metropolis is a parody of the rich-poor division manifesting itself in the between-wars Weimar Republic — and echoed today. Between the upper and lower levels is the Machine Level, where the workers put in their toilsome hours.

Our hero, Freder, wanders into this level, where he sees the great machine overheat and explode, scalding and killing scores of workers. He is horrified and hallucinates the machine turning into “Moloch,” devouring its human sacrifices.

He comes across Worker 11811, working a mysterious machine, who collapses from overwork and Freder takes his place. The scene recalls the famous Leonardo drawing of the “Vitruvian Man.”

The whole underworld is a purgatory, and below the Workers’ City there are the catacombs, where the virtuous Maria lectures the workers about justice — and the importance of waiting for a “mediator.”

This is not a movie about people, but about archetypes. There is father, son, city, death, all presented almost naked, with little attempt to disguise them as anything real.

The world is divided, in Nordic and Wagnerian style into an underworld, a middle world and an upper world. The catacombs are deep caves, and the home of religion and myth.

The Workers’ City and their machines are in the middle.

And the privileged world of the elite rides above it all, and depends on all that resides — like a subconscious — below, normally unseen and unthought of.

The architecture is a strange mix of the Moderne (Art Deco and German Expressionist); the dull efficiency of a Socialist utilitarian greyness; and relics of the Gothic; and prehistoric caverns.

The main characters are the father, Joh Fredersen, who is master of the city; his son, Freder; the mad scientist Rotwang; and, most central of all, the woman, Maria.

Fredersen (looking suitably Napoleonic); Freder; Rotwang; Maria

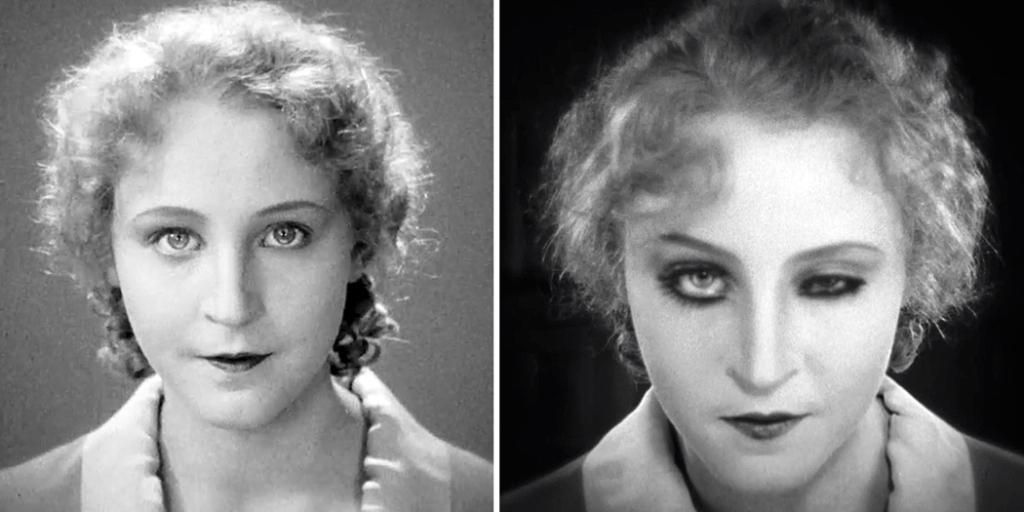

Maria, played by Brigitte Helm, is the central and most interesting character. She is really two characters, and the embodiment of two archetypes: virgin and whore. Rotwang creates a robot in the form of Maria and programs her to undo everything the good Maria has done. Helm differentiates the two personae in a way that they cannot be confused.

The two Marias separate in the very Frankentsteinian laboratory of Rotwang, in one of the most hypnotic sections of the movie, with rings of light rising and falling around the body of the robot,

until it takes on the visage of the good Maria.

This Bad Maria, or False Maria, is sent to the workers to foment rebellion (why is never really made clear — it doesn’t make any sense, economically, to destroy the whole city), and she turns up in a nightmare hallucination of Freder as the Whore of Babylon, dancing at the Yoshiwara cabaret, doing a provocative dance.

And morphing into a Medieval vision of Die Grosse Babylon — the Great Babylon, from a verse in the biblical Apocalypse.

Which drives the men at the cabaret crazy with desire.

When the film was released in the U.S., Variety magazine’s reviewer commented: “Some sex stuff here and there, and a cooch dancer! Yes, sir, a coocher, in the revigorated mechanical figure, and a pretty good coocher, too, but not so thick around the hips as German coochers generally are. But then you must remember that this young lady was made to order.”

This False Maria persuades the workers to destroy the machines, which automatically floods the Workers’ City (don’t ask why), threatening all the children, and the workers, horrified, burn the False Maria at the stake, where, of course, she turns back into the robot.

Not to worry, Freder and the Good Maria save the children.

The film is shot through with biblical references, not for theological reasons — there is no actual religion in the movie — but as cultural markers, symbols that will resonate with an audience familiar with the Bible.

In the catacombs, the Good Maria teaches a lesson about the Tower of Babel, and how the conceivers of the tower failed to teach the workers who made the tower why they should do so, and a rebellion ensues and the tower is destroyed.

In Freder’s fever-hallucinations, the figures of the Seven Deadly Sins, from the cathedral, step down from their pedestals and the figure of Death comes to life.

And Death approaches Freder with his scythe.

There’s Freder’s vision of the exploding machine as the biblical Moloch

And the movie comes to its climax when Rotwang abducts the Good Maria and chases her to the top of the cathedral, among the gargoyles.

And drags her to the very rooftop, where he fights it out with Freder.

While his father (remember him?) falls to his knees in fear among the crowds in the parvis.

But Rotwang falls to his death and Freder saves the Good Maria, leading to the point where Maria gets the heart (Freder) to mediate (shake hands) between the hands (the worker) and the head (Joh Fredersen) and therefore satisfying the prediction of the opening epigram of the movie.

It’s rather a sappy ending for so visionary a movie. But then, the plot has never been the point.

Which is something novelist H.G. Wells didn’t seem to understand when he reviewed the film on its release in 1927. In his piece for The New York Times, he wrote, “I have recently seen the silliest film. I do not believe it would be possible to make one sillier.”

His beef was that the film didn’t realistically portray the future.

How can it, when Rotwang’s Medieval house in the middle of the city is, like the Tardis, bigger on the inside than on the outside?

Its economics didn’t make sense, Wells wrote. “The machines make wealth. How, is not stated. … One is asked to believe that these machines are engaged quite furiously in the mass production of nothing that is ever used, and that [Fredersen] grows richer and richer in the process. This is the essential nonsense of it all.”

Where are the suburbs? Wells asks. Why, in the future, do all the cars look like the Model T? Where in the catacombs under the city are all the gas mains, sewer conduits and electrical infrastructure? His literal-mindedness is comic.

How can you be literal when the clocks in the film cannot even agree on how to measure time — Salvador Dali must have been their clocksmith.

Wells goes on and on, completely missing the point. Obviously, Metropolis was never intended to be realistic. It is not even meant to be the future. It exists in no time, according to both Lang and Harbou. It is a fever dream, an oneiric fantasy, and the glories of the film are all to be found in its visuals, not in its story.

You can watch the film on YouTube in decent resolution, and it is available on DVD and Blu-Ray. It is one of the great films of all times, and one of the most memorable.

Lang went on to make such great films as Woman in the Moon, also with Helm; M, with Peter Lorre; The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, with Rudolf Klein-Rogge (Rotwang from Metropolis); then, in Hollywood: Fury, with Spencer Tracy; Rancho Notorious, with Marlene Dietrich; and Clash by Night with Barbara Stanwyck. And many other great films. But none burrows into the brain in quite the same way as Metropolis.

Click on any image to enlarge