I recently discovered Glazunov.

Discoveries are what keeps life interesting. Some are life-changing, like when you first discover the opposite sex, or late in life encounter the music of Bruckner. Others are just a pleasure you hadn’t known the universe afforded, such as chipotle chiles or books by David Sedaris.

Glazunov is one of the latter. I don’t want to make too big a case for him, but his music is effortless enjoyment.

Alexander Glazunov was a Russian composer, born in 1865, the same year as Sibelius and five years after Mahler. He grew up in a Russian musical world split between nationalists and internationalists. On one side, you had “the Mighty Handful,” of largely self-taught composers, such as Glinka, Borodin, Balakirev, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov (the last distinctly well-trained), all of whom wanted to create a genuinely Russian brand of music. On the other side were Tchaikovsky, Anton Rubinstein and others, who looked to Germany and western Europe for their influence. It was isolationism vs. assimilation.

Glazunov, born into this world, was a prodigy and he was taken on as a student by Rimsky-Korsakov when little Alexander was still a high school student. “His musical development progressed not by the day, but literally by the hour,” Rimsky-Korsakov wrote. Young Glazunov excelled in counterpoint, harmony, orchestration and large-scale form. It seemed he could do anything.

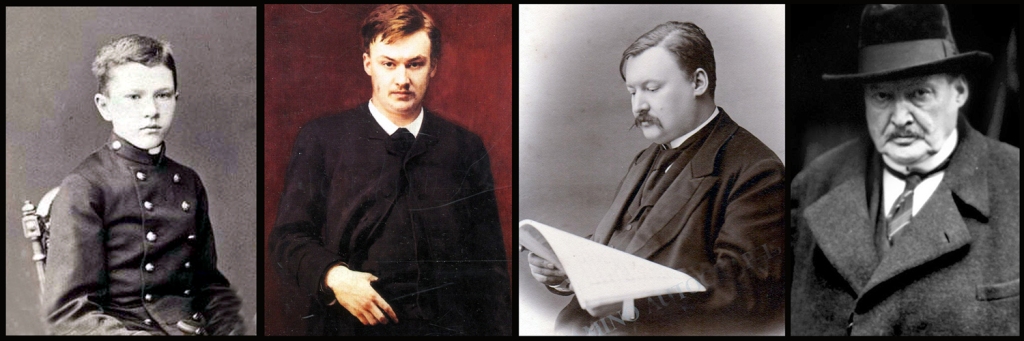

His first symphony was performed when he was just 16, and was a huge success — the audience was astonished when the composer came onstage to accept their applause and turned out to be a kid in his school uniform. It was unofficially titled, “The Slavic Symphony,” for its use of Russian and Russian-style melodies, and it would have seemed as if the young composer was going to launch a new generation of nationalist composers. (To put the symphony in context, when it was written, Tchaikovsky had only written four of his six symphonies.) It joins Bizet’s Symphony in C and Shostakovich’s First Symphony as prodigies of teenage composers.

Glazunov as student, young man, middle aged and old

But Glazunov’s second symphony, written only five years later, was “dedicated to Franz Liszt,” and clearly showed Glazunov gazing westward to more modern musical influences.

In all, Glazunov wrote eight symphonies and part of a ninth. Every one of them is a joy to hear, full of great tunes, rich harmonies, fresh orchestration. His style is seen now as conservative and old fashioned, but while it is always familiar, it is never clichéd. He finds new ways of using the old composing tools.

His music also never attempts to move heaven and earth, like Bruckner or later, Mahler, but rather attempts to please, to keep his listeners entertained. For this, he has sometimes been belittled and, as the 20th century progressed, largely forgotten.

But you need to remember that most of Mozart’s output was simply meant to entertain, also, and it is a worthy goal. Glazunov’s music is a delight. Beethoven may churn our souls, but Glazzy just wanted to show us something of beauty and craftsmanship.

That doesn’t mean all his music is major-key bouncy and empty. There is plenty of introspective substance, and the occasional disruption to remind us that the world isn’t always placid. But it is all to the end of keeping our ears interested.

St. Petersburg Conservatory, ca. 1900

As his career developed, he became a respected member of the Russian art establishment, and eventually became head of the St. Petersburg Conservatory, where he trained many younger musicians, most importantly, Dimitri Shostakovich. His tenure was marked by a great improvement in the conservatory’s reputation and the quality of its instruction. Glazunov took his directorship seriously.

He ran the school from 1905 to 1930, and while the instruction remained rather conservative, built on the principles of 19th century romanticism, its students entered the new century with other ideas.

“Glazunov was ‘born in the middle,’ so to speak,” wrote critic Leo Eylar. “He was born a generation later than the initial great Russian composers such as Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, and was born a generation before the modernist revolutionaries such as Stravinsky, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich. As such, he was destined to occupy a rather difficult position in Russian music history.”

Glazunov continued writing music into the 1930s, and by then seemed like some musical dinosaur. But it is important to remember that he was 32 before Brahms died. His taste was formed before Modernism was even thought of.

St. Petersburg

He was born in czarist Russia and lived through the Communist revolution and into the Stalinist era. He held the conservatory together during some tumultuous years, and with considerable integrity. When he was offered honors (and extra pay) by the regime, he replied asking for some firewood instead, so the students could heat their classrooms. During the privations of the Revolution and civil war, many students were near starvation and would have died but that Glazunov ensured they were given scholarships and the food allowance that came with them.

“This was a period of terrible famine,” said Shostakovich. “The gist of the scholarship was that its possessor was able to receive some groceries. In a word, it was a question of life and death. If you’re on the list, you live. If you’re crossed off, it’s quite possible that you may die.”

Shostakovich was on the list.

And when an increasingly anti-Semitic government required he list the names of all the Jewish students, he sent back a message: “We don’t keep track of such things.”

He listened carefully to his students’ music, even if he was sometimes shocked by it. He attended all of the school’s recitals. If he didn’t like something, he would listen over and over until he understood what was being attempted. This quality made the young Shostakovich love his schoolmaster.

“After the Revolution, everything around Glazunov changed and he lived in a terrible world that he didn’t understand,” Shostakovich said. “But he thought that if he died, important work would perish. He felt responsible for the lives of hundreds of musicians, so he didn’t die himself.”

Shostakovich describes his perfect pitch, his ability to spot any mistakes in a student’s composition, like hidden “parallel fifths,” and his astounding memory. When Borodin died, leaving his opera, Prince Igor, unfinished, Glazunov reconstructed parts from memory, having heard Borodin play them on the piano years earlier.

He understood the instruments of the orchestra. He learned to play the violin well so he could write his violin concerto. Once, visiting London, a french horn player complained that a note in the score was “unplayable.” Glazunov picked up the horn and played the note for him.

“And Glazunov played the piano well,” said Shostakovich. “He didn’t have a real piano technique and he often played without removing his famous cigar from his right hand. Glazunov held the cigar between his third and fourth fingers. I’ve seen it myself. And yet he managed to play every note, absolutely everything, including the most difficult passages. It looked as though Glazunov’s fat fingers were melting in the keys, drowning in them.”

On the minus side, though, Glazunov was a lifelong alcoholic, who kept a hidden bottle of hooch in his office desk, with a tube running from the desk drawer to his mouth, so he could sip while discussing music with his students. His alcoholism is sometimes blamed for the disastrous premiere of Rachmaninov’s First Symphony, which Glazunov conducted in 1887. The performance was so disastrous that Rachmaninov stopped composing for three years.

During his life, Glazunov’s music was held in high esteem, especially in Russia. But as the 20th century began, his music was seen as more and more out-of-date. His efforts at the conservatory slowed his musical production, and by the time of his death in 1936, only his violin concerto remained in the active repertoire, helped mainly by the fact that virtuoso Jascha Heifetz played it frequently.

Glazunov gave up active directorship of the conservatory in 1928 and left Russia. He never expressed any political concern, but it was clear that Stalinism was not going to put up with Glazunov’s independence of spirit, and so the composer moved to France, where he remained until his death.

In all, Glazunov composed eight symphonies, with a fragment of a ninth. He also wrote several multi-movement orchestral suites, which might as well be counted among his symphonies including From the Middle Ages and The Kremlin. He composed several successful ballets that continue to be staged even in the 21st century, most famously, Raymonda and The Seasons.

He was a master of orchestral color and orchestration, and handled the large forms admirably. Especially his inner movements — the slow movements and the scherzi — are memorable and moving. He was fond of unequal phrase lengths, which kept the melodies from being predictable or monotonous (a problem that often beset Robert Schumann, who too often fell into 8- or 16-bar patterns).

Glazunov wrote a handful of concertos, among them the popular violin concerto and, as his last major composition, a concerto for alto saxophone, which is quite forward-looking for the old master. There are a pair of piano concertos and some concertante works for cello.

But for me, his real masterpieces are his quartets. He wrote seven numbered quartets, a Suite for string quartet, and his Five Novelettes, a full-length Elegy, and a Quintet for strings. These works highlight what Glazunov was best at.

Quartet writing after Beethoven became a problem for many subsequent composers. The importance and depth of Beethoven’s quartets, especially the dense late quartets, tended to lead later composers to approach the form with such utter seriousness that they become clogged with polyphony (ahem: Reger) and the need to keep each string player occupied all the time. There are exceptions, like the quartets of Dvorak, but even Brahms gummed up his string quartets with thickness.

Glazunov, however, could write counterpoint with clarity and grace. Many of his quartets start with a fugal introduction, but you never get the feeling that he is writing an obligatory chunk of polyphony to prove his seriousness. Rather, his fugues flow like real music, charming and direct.

The quartets have almost orchestral color, as Glazunov alternates timbre with changes in register, double stops, muting, harmonics, and pizzicati. You never tire of the string tone, it is always varied.

He splits the melodic material among his players so that everyone gets a turn with the big tunes. Glazunov wrote his quartets primarily for his friends to play among themselves, and I think they must have been a joy to perform, even more than to listen to. It’s a mystery to me why they don’t show up more often on recital programs. Audiences would love them.

For his symphonies and concertos, there is an inexpensive box set on Warner Classics, conducted by Jose Serebrier that is, I think, the best currently available set. There are other versions with Vladimir Fedoseyev and the Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra of Moscow Radio, in somewhat lesser sound engineering; and Naxos has its series of Glazunov’s music, with the symphonies conducted by Alexander Anissimov and the Moscow Symphony Orchestra. Serebrier beats them all with sound, performance and price.

As for the quartets, there is a complete set box with the Utrecht String Quartet that is beautifully played and recorded, on MDG. You can get them individually played by the St. Petersburg String Quartet and several by the Shostakovich Quartet.

And, since everything — and I mean everything — is available on YouTube, you can find multiple versions of almost everything Glazunov wrote, often with the musical scores to read as the music plays.

I am not making the case that Glazunov should be seen as some forgotten Brahms or Dvorak. His music lacks the emotional and philosophical ambition to take on the deepest meanings you find in Beethoven, Wagner or Mahler, but none of the big names can claim supremacy in terms of technical proficiency or tunefulness. Glazunov wrote music, and seen in purely musical terms, he was a great master.

Much art and music from before the First World War fell out of favor with the rise of Modernism. Glazunov fell with them. But now that Modernism is old-fashioned, we can reappraise a good deal of work that was denigrated in the 20th century. Rachmaninov no longer has noses turned up at his music. Even academic painting from the second half of the 19th century is finding new audiences. Glazunov deserves to be among the rediscovered.