Kitao Shigemasa “Birds in Yellow Plum”

Recently I posted a piece about the history of naturalist illustration. It was a subject so huge — and with so many gorgeous images, that I could not begin to include some of my favorite things from the thousands of images I collected.

For instance, I had to rule out all of the non-Western art, and some of my favorite non-scientific animal art. And so, I felt I should write a follow-up piece for a few of the leftovers.

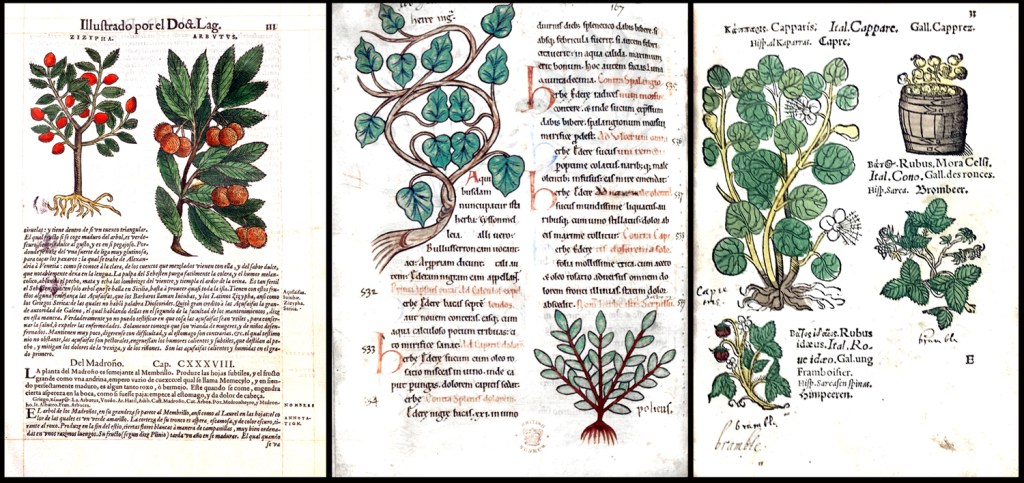

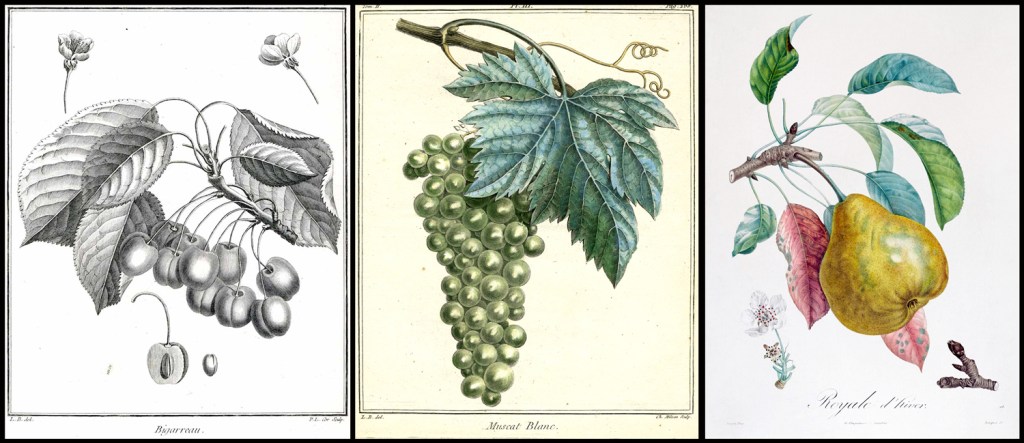

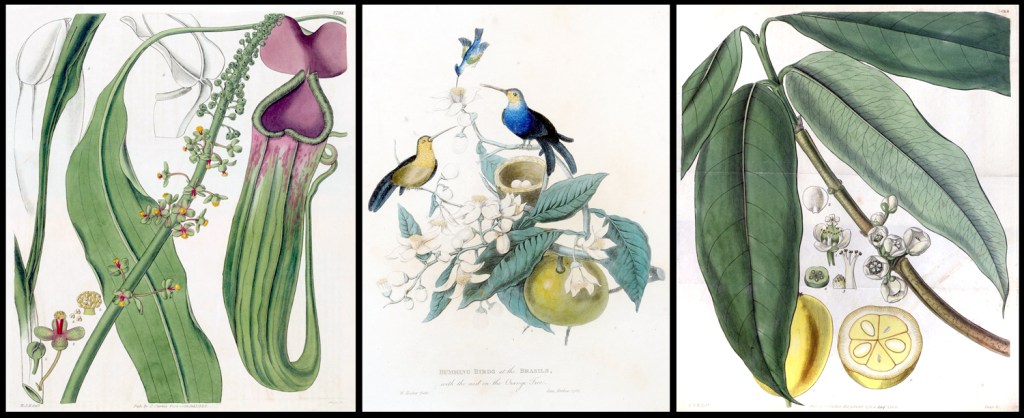

Most of the art I covered was meant to illustrate botanical collections in an era when new plants were constantly being added to the list of recognized species, and were meant to accompany scientific books written by specialists.

From “Plantae Asiaticae Rariores” of Nathaniel Wallich

For instance, there was Nathaniel Wallich, the Danish-born botanist who collected plants in India and published his Plantae Asiaticae Rariores in three volumes from 1830 to 1833, with illustrations by a half-dozen artists, both Indian and European.

From “Treasury of Nature,” Albertus Seba

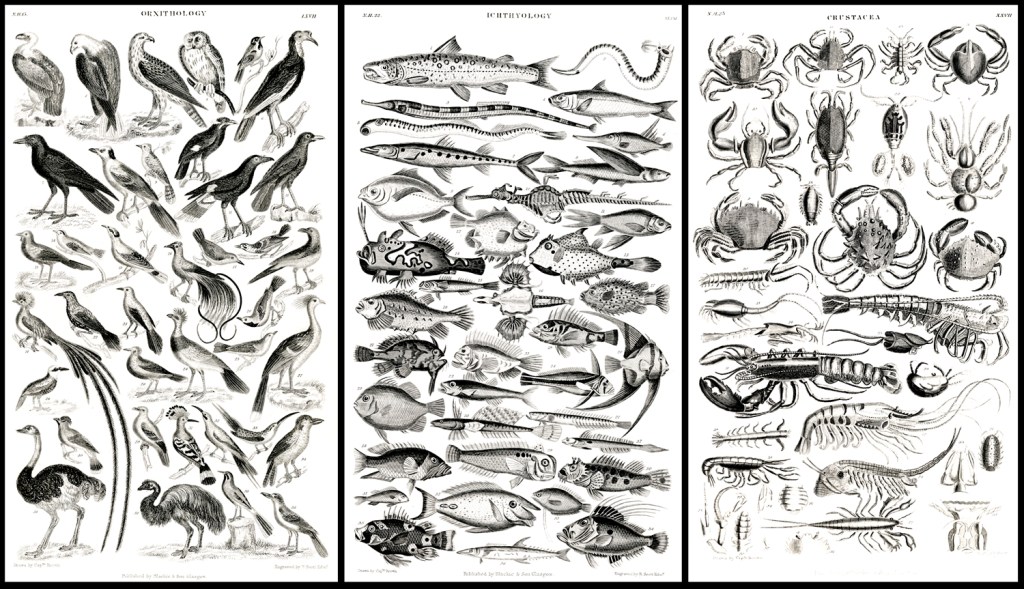

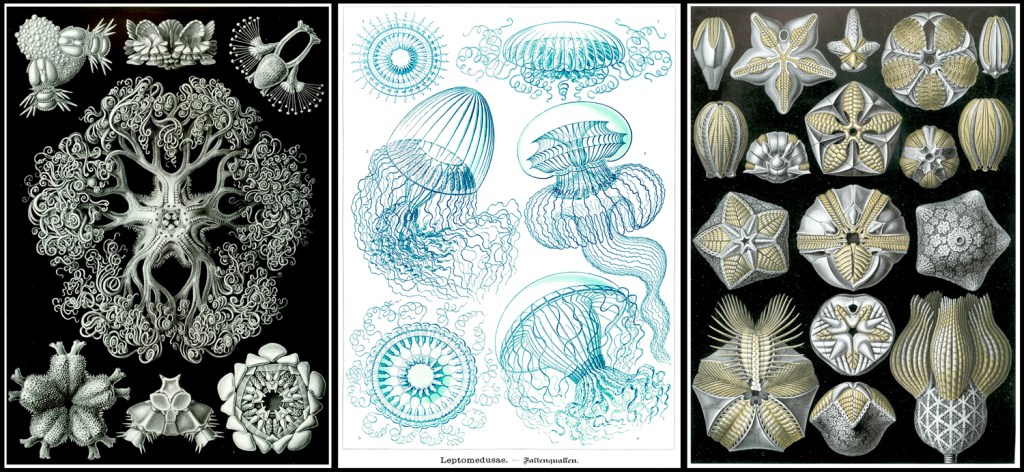

The collection I missed most in the earlier essay was Albertus Seba (1665-1736). His interest was less scientific and more one of abject curiosity. He collected tons of oddities from around the world in his “curiosity cabinet,” and in 1734 published his Locupletissimi Rerum Naturalium Thesauri Accurata Descriptio et Iconibus Artificiosissimus Expressio per Universam Physices Historiam (“A Careful Description and Exceedingly Artistic Expression in Pictures of the Exceedingly Rich Treasury of Nature Throughout the Entire History of Natural Science,” illustrated from beginning to end with engraved plates.

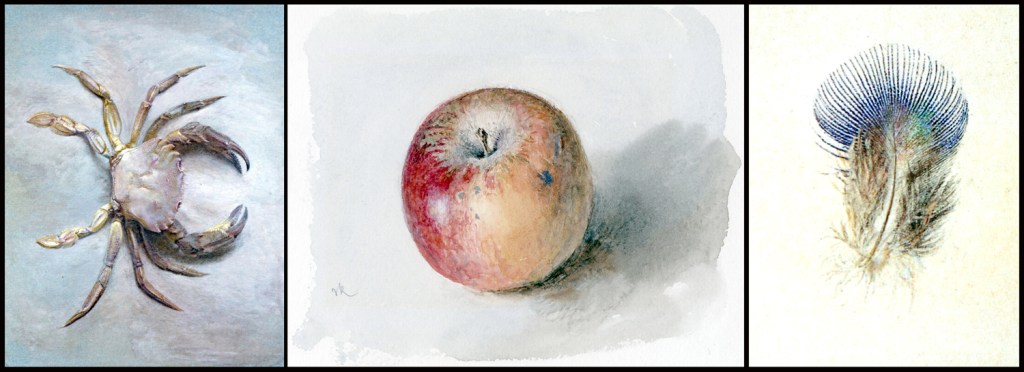

Crab from Albertus Seba

The original 4-volume publication included 445 illustrations and Seba’s collecting helped Carl von Linne in his binomial classification system.

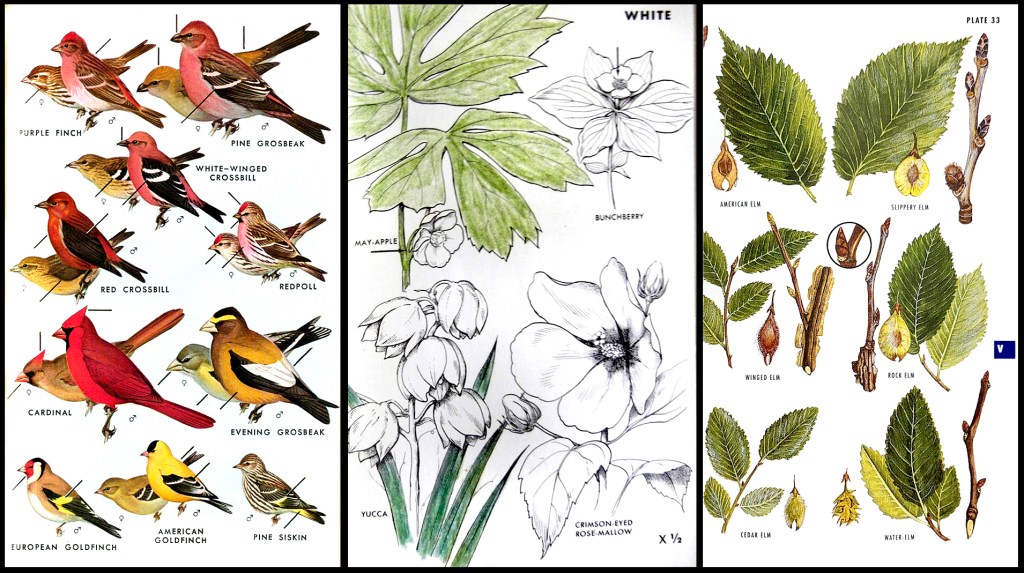

But, there are tons of bird, plant, and animal pictures meant for the general public, mostly throughout the 19th century.

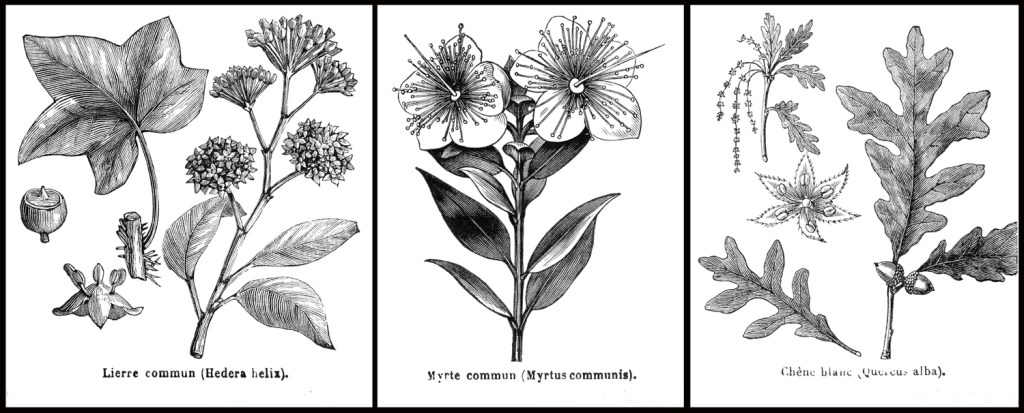

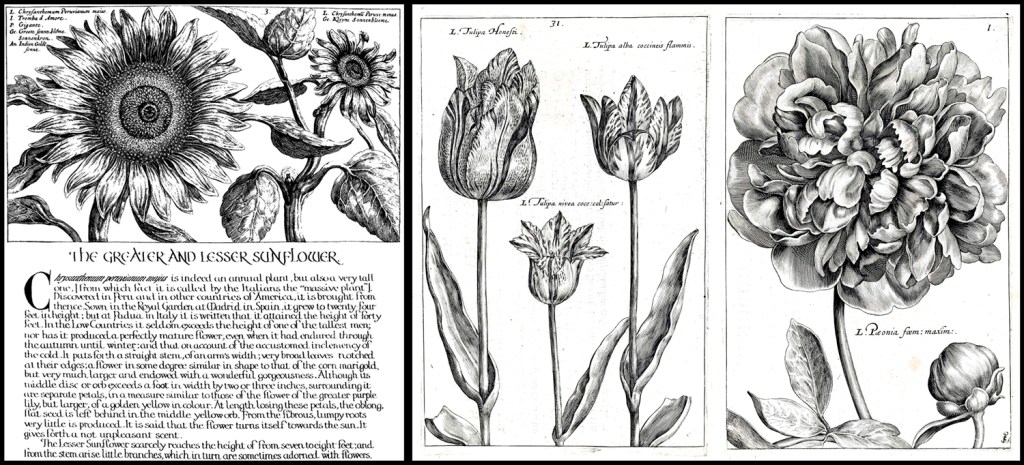

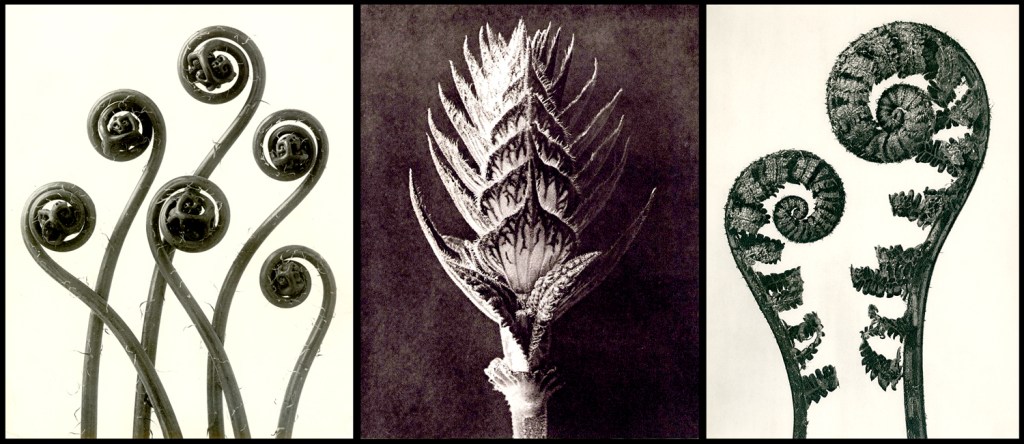

Wood engravings of plants

Unfortunately, most of those artists worked anonymously, pumping out pictures for books, magazines and posters. Animals, especially those of exotic locales, were always popular pictures with the public. And most of those were made in the process called wood engraving — a bit like woodcuts, but made with a burin on the end-grain of dense hardwoods and printed very like a copper plate engraving.

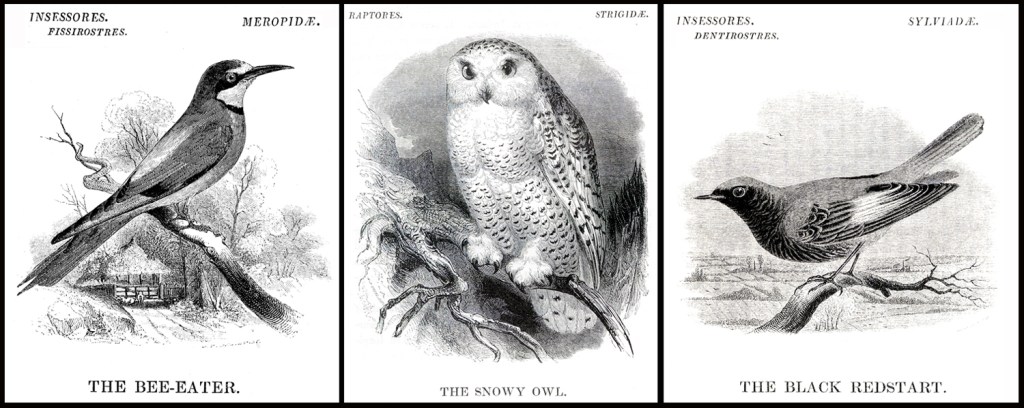

Wood engravings of animals

The best-known wood engravings were probably the book illustrations of Gustave Doré. But the technique was nearly ubiquitous in the Victorian era.

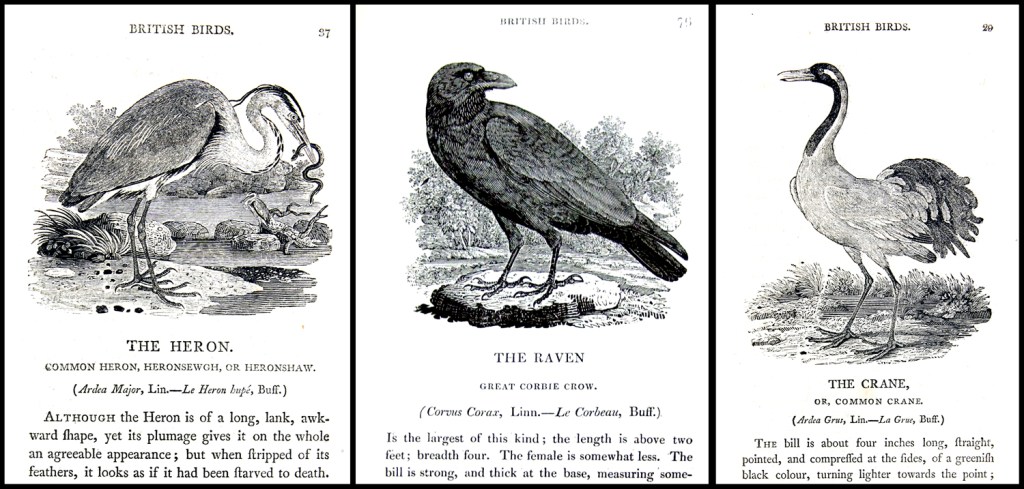

From “A History of British Birds” by William Yarrell

Wood engravings occasionally accompanied serious scientific work, also, such as those in A History of British Birds, published in 1843 by William Yarrell (1784-1856). Its wood-engraving illustrations were carried out by two artists, Alexander Fussell and John Thompson.

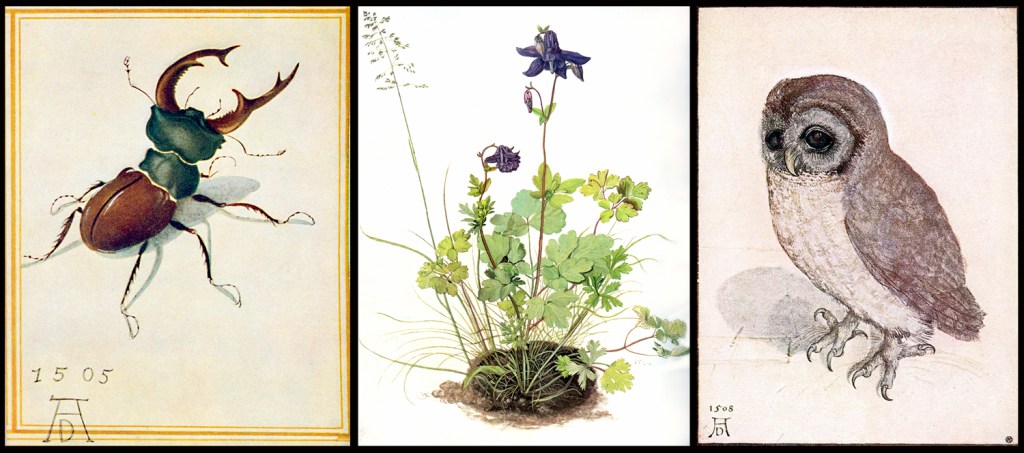

Such art is meant primarily to identify plants and animals, but sometimes an artist’s intent is merely to look closely at and study his subject. And, as with the botanical illustration, to separate the subject from its context to better see it on its own.

Drawings by Leonardo da Vinci

Artists have always done this, often in sketches, sometimes as studies for larger, more serious and integrated paintings, sometimes purely for its own sake. Leonardo drew lots of them.

Drawings by John Ruskin

And it was the very point that critic John Ruskin made in Victorian times for the art of drawing: He felt that sketching forced close observation and that essence was found in detail. He aimed his eye at plants, birds, even rock formations, to come to know them better.

Drawings by Ruskin

The most significant class of nature art left out of my original essay are the many kachō-e prints and paintings by Japanese artists, ranging from the 17th century to the 20th. I was sorry to leave them out.

Masayoshi, “Gray Thrush”

Kachō-e are so-called “bird and flower” pictures, although the subjects include fish and insects, too. Their ancestry runs back to huaniaochua (“bird and flower” paintings) popular in Chinese beginning in the Tang dynasty (AD 618-907).

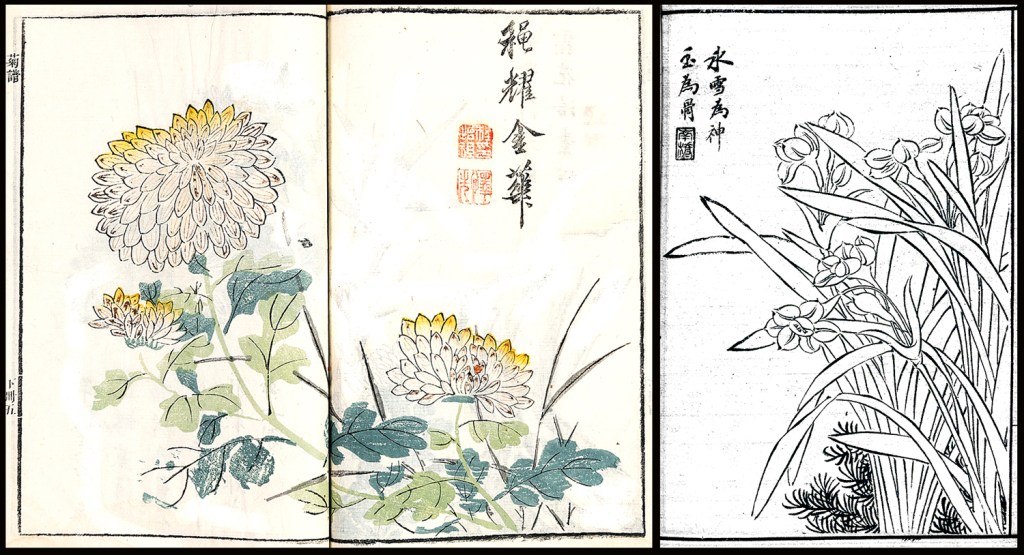

The work influenced much of art throughout Asia, and came to Japan, popularized by translations of the Chinese classic instruction book, Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, published in parts from 1679 to 1701. The final chapters instruct how to best paint huaniaochua-style art.

Pages from “Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden”

The Chinese influence was felt all through the continent, not only in Japan and Korea, but as far west as Persia, where it inspired the golomorgh (“Bird and Tree”) paintings popular in the Safavid period (1501-1736).

Golomorgh art

In Islamic art, the paintings take on an allegorical bent, with the birds (sometimes butterflies) standing in for the lover and the flower for the beloved.

But by far the biggest influence was in Japanese art, and the popular ukiyo-e style, mostly woodblock prints made from the 18th through the early 20th century. Ukiyo-e (“Pictures of the floating world”) were popular images of famous actors, courtesans, historical figures, landscapes, genre scenes — and nature. The nature genre was called kachō-e, or “bird and flower pictures.”

One of the early masters of the form was Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806). He published a Book of Birds ca. 1790 (the dating is often uncertain, as records were not always kept, and popular books were published and republished, often with new plates, or new cuttings of old designs — precise dating can be guesswork).

Each image was matched to poetry, written in elegant calligraphy on the empty parts of the image. For this one, named for the mejiro, or Japanese White-Eye (on the left) and the enaga or Long-Tailed Tit (on the right) has two poems. The first: “Pushed out of his honey-filled nest following a fight, the white-eyes bird seems not to mind at all,” while the other says “Come and let yourself be mine; For us the nights will be as long as the tit’s tail.”

Utamaro followed with a Picture Book of Selected Insects, about the same time, which showed dragonflies, beetles, bees, grasshoppers and other buggy life on beautifully drawn leaves and flowers. When Viking Press published a beautiful facsimile edition of the book in 1984, they must have worried about the title, so they renamed it Songs of the Garden. Much more attractive.

In the west, the two most famous ukiyo-e artists are Hokusai and Hiroshige, near contemporaries. They both made kachō-e prints.

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) called himself “Old Man Mad with Painting,” and worked in every conceivable genre. He was a one-man image factory. His curiosity spanned everything he could come in contact with. He even experimented with linear perspective after coming in contact with European art.

Hokusai manga

In his sketchbook, or manga, he made pictures of everything he saw. The black-and-white drawings were made into woodblock prints. He tried just about everything. (Most famous, of course, for his “Great Wave off Kanagawa,” which has been reproduced endlessly.)

There is a proverbial saying in Japan: “Hokusai is the greater artist, but I love Hiroshige more.” It is hard not to be entranced by the atmospheric and almost Impressionistic work of Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). Known for his landscape images, he also made a pile of bird-and-flower prints. Most often in the elongated vertical format known as hosoban.

There are so many of them, it is hard to choose just a few examples.

But he also published several books of fish and sea creatures, a “small” book of fish and a “large” book, each titled as such. I cannot help but post as many of Hiroshige’s images as I can. They are so seductive and beautiful.

It is usually said — by snooty connoisseurs — that ukiyo-e standards began to decline in the 19th century and the genre ended by the 20th. But instead, I believe it simply changed with the exposure of Japanese artists to the rest of the world with the Meiji Restoration (1868). Where once Japan’s culture was insulated from the outside, it now opened its arms to new influences.

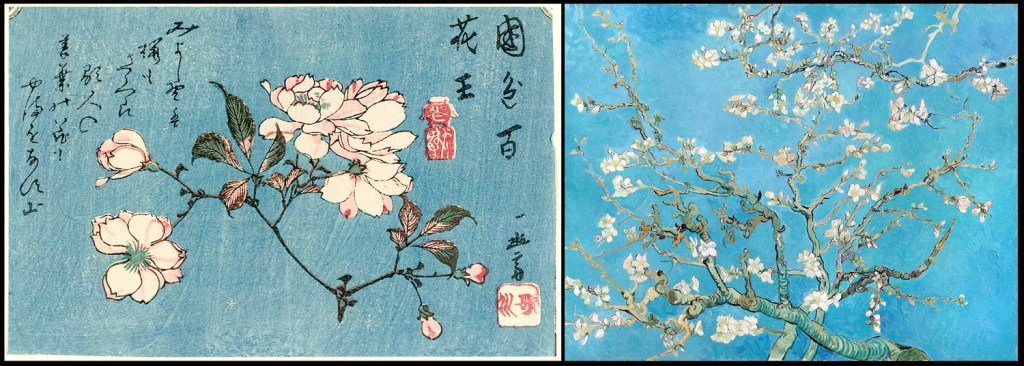

Hiroshige and Van Gogh

(The artistic fertilization went in both directions, as ukiyo-e art began arriving in Europe and artists such as Van Gogh were blown away by the freshness and style of the Japanese prints.)

And kachō-e changed from a popular and demotic art form to one created by new designers who saw themselves less as craftsmen and more as western-style “artists.” The esthetic, called shinsaku-hanga, became more refined, if less adventurous. It was a retrospective art, honoring the masters and styles of the past.

Birds by Kono Bairei

And artists such as Kono Bairei (1844-1895) continued the birds-and-flowers tradition, but with a turn to more naturalistic drawing, albeit in a stylized setting.

Bairei fish

He also took on fish.

The work of Imao Kainen (1845-1924) maintains that almost-western realism in highly decorative compositions.

By Imao Kainen

The most famous of the shinsaku-hanga artists was probably Ohara Koson (1877-1945). He was a teacher at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, and met American scholar Ernest Fenollosa, who encouraged him to export his bird prints to America. His work now sits in most American art museum collections.

By Ohara Koson

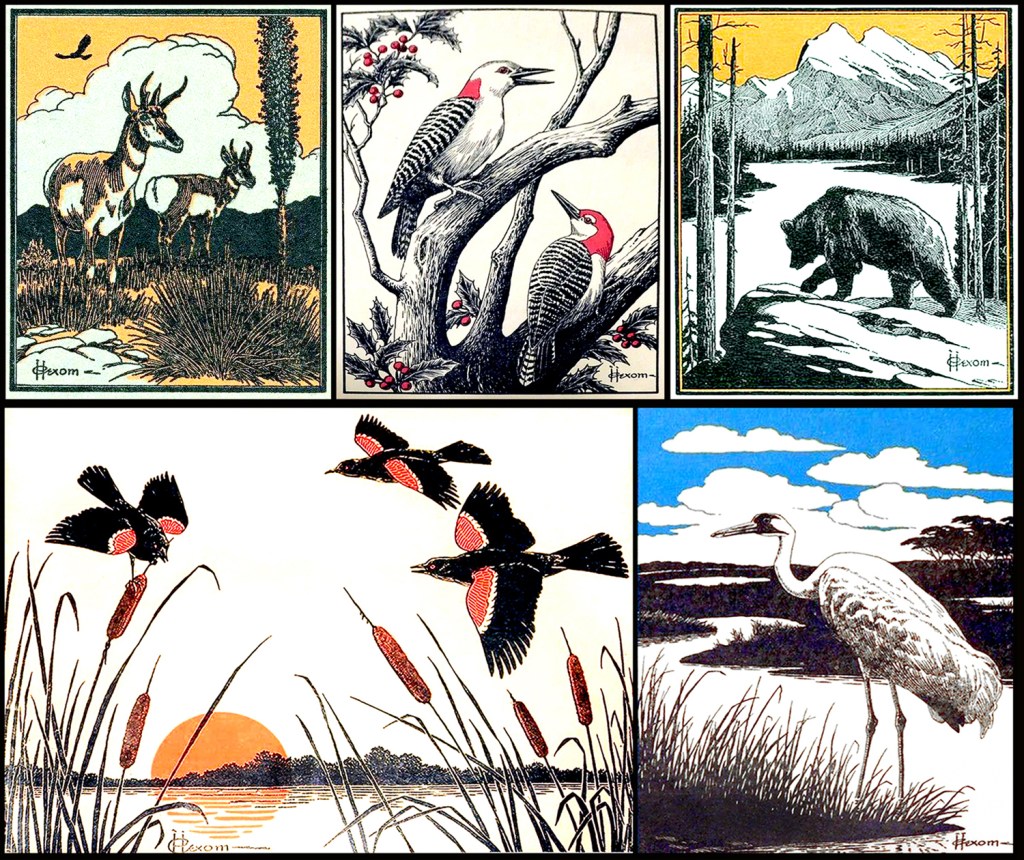

It wasn’t only Van Gogh who responded to the Japanese style. One of my favorite and largely unknown illustrators of natural history was Charles Philip Hexom (1884-1959). He was a teacher at Luther College in Dacorah, Iowa, and made many cover illustrations for Nature Magazine from the 1920s into the early ’50s.

The use of flat outlining and spot-color were common to both ukiyo-e and Hexom’s covers.

I don’t know why the work of Charles Hexom hasn’t been collected and published in a book. He seems to have been forgotten. He deserves to be remembered.

Beatrix Potter watercolors

Nature art may be a sub-genre in the world of fine art, but it is a fertile one. One finds captivating and beautiful illustration everywhere. Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) before she became a children’s author, used her drawing talent to study nature. She became an expert on mushrooms and fungi. One of her admirers was the Pre-Raphaelite artist Sir John Everett Millais, who told her: “Plenty of people can draw, but you have observation.”

Again, I have left out so much. So, just as a little P.S. to this tiny essay, I want to mention the early paintings of my brother-in-law Mel Steele, who could paint rings around anyone even as a boy and moved on to bigger things and a long career.

And my own minor essay into the field as a photographer. I found that I could put live flowers on my flatbed scanner and get beautiful prints that could be reproduced in fine detail at almost any size.

Friesia, iris and daffodils

I have made many photographs of flowers, birds and insects, not so much to create art as to focus my attention on the world around me. Paying attention is, I believe, the prime directive for life.

Click on any image to enlarge