Early years in Dodge City

It began when I was watching syndicated reruns of old Gunsmoke episodes and I couldn’t help, as an adult, but wonder, “Where do all these people live?” I mean, there didn’t seem to be any houses in Dodge City.

Yes, we saw that Marshall Dillon slept on a cot in his office and that Miss Kitty had a room at the back of the saloon, and Doc Adams had an apartment attached to his surgery. And perhaps Sam the bartender had a room upstairs at the Long Branch and perhaps Jonas had a second-floor apartment above his general store. But the town was fully populated with people and the only street we ever see on Gunsmoke is lined with shops and businesses — at least two saloons, the Dodge House hotel and a restaurant where the gang often dined. Where were the houses?

I know it’s not really important. Westerns are America’s foundational myth, and like myths from the time of Gilgamesh through Ancient Greece and up to Gunsmoke, we don’t ask realism of the stories. They are moral tales, parables, etiologies, and euhemeristic histories. Unnecessary detail just clutters up the telling of the tale. As I said before, no one asks if Hercules had a mortgage.

But the issue of Dodge City housing interested me nonetheless.

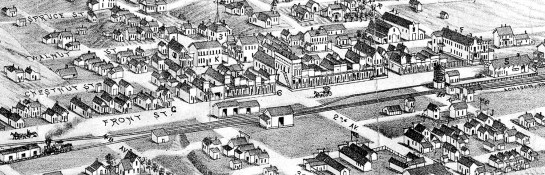

I found an old map of Dodge City from 1882 and there were plenty of houses along the side streets that led off from Front Street, the main road of the town. There were four churches, a courthouse, a school, a grist mill, an Odd Fellows Hall, a railroad depot, a newspaper office and at least four hotels, including the Dodge House, Cox & Boyd, proprietors.

Admittedly, 1882 is about five or six years later than the fictional Gunsmoke Dodge was supposedly set (according to its creators), but it should tell us something about Western settlements of the era. Yet, except for a few episodes of rowdy trail hands shooting up the place, Gunsmoke rarely mentions either the railroad or the cattle business. Where are the cattle pens? Why does no one ever mention the stink?

Then I discovered a trove of historical photographs from the Gunsmoke era and pored over them for what they might tell me.

Gunsmoke, first on radio and then on TV for 20 years was intended as an “adult” Western, with more grown-up plots and themes than the standard cowboy movie. And in the early years, largely succeeds, with some quite grim stories about the difficulties of life on the prairie. But even given that, the series relies on many of the Western movie tropes, including its sense of how a Western town is built and functions: one main street lined with storefronts and saloons.

As I have said, I am not asking a television entertainment to be a documentary, and I am not complaining that Matt Dillon’s town had little to do with the historical Dodge City. But I couldn’t help but want to find out what the reality might have been.

Ruts still visible from the Santa Fe Trail, near Dodge City

A little background: Once, there was a piece of land in the middle of the continent halfway between another piece of land controlled by people speaking English and another piece of land controlled by people speaking Spanish. And the English- and Spanish- speaking peoples wanted to do business together and so wagons of goods moved from one side of America to the other side along familiar routes that eventually became well-worn trails. The one we’re concerned with was called the Santa Fe Trail.

Of course, the parcel of land between them was not empty, but occupied by native peoples, who sometimes took exception to the Europeans who trespassed over their land, and so, the English-speaking peoples sent out their army to build forts along the trails to protect the merchants and their teamsters, and later to protect the European immigrants who wanted to live in the middle of the continent or travel across it to get to the parts further west.

Fort Dodge in 1879 and General Grenville Dodge

And so, on April 10, 1865, a company of soldiers from the Eleventh Cavalry Regiment under orders from General Grenville M. Dodge established a camp on the Arkansas River along the Santa Fe Trail. Lacking building materials, they made dug-outs into the river banks for shelter. Dodge later wrote in his autobiography that the soldiers sarcastically named the place after him because they “were so mad at being sent there .. with so little accommodations that they named the place Camp Dodge.”

Arkansas River near Fort Dodge

Sidenote No. 1

Researching history can be a nightmare. There are ambiguous and conflicting sources everywhere. Dates are in question, name spellings are helter skelter, tall tales sometimes intrude with frequently told-fictions. First-hand accounts often appear to glorify their authors. I have tried to relate the most dependable version of Dodge City’s history, but there are sometimes smudgy areas.

For instance, Grenville Dodge isn’t the only Dodge involved, and sometimes one of the others gets credit for the fort’s name. In 1851 a Col. I Dodge established a fort to protect the Santa Fe Trail in Kansas. The fort proved temporary. Gen. Grenville Dodge ordered the construction of Fort Dodge near what is now Dodge City in 1865. Later, in 1872, the fort was commanded by Col. Richard Irving Dodge. Confusion seems inevitable.

Back to our story

The camp was soon refurbished with sod house buildings and then wood and stone buildings and officially became Fort Dodge and manned by up to four companies of soldiers.

Henry Sitler in later years, and his sod house in 1871

In 1871, rancher Henry L. Sitler built a sod house about five miles west of the fort, which became a stopping place for those traveling on the Santa Fe Trail, and a year later, a town was platted and George M. Hoover set up a tent to sell liquor to the soldiers at the fort. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway arrived in town later that year and things picked up quickly.

At first it was the trade in buffalo hides that built Dodge City, with the bones and skins of the buffalo sent by rail back to the east. Indeed, the settlement was first named Buffalo City.

Buffalo hides at Dodge City

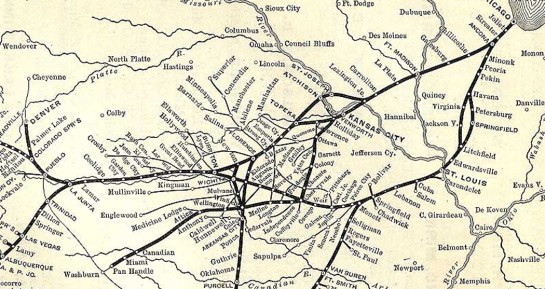

When cattle from Texas needed to be shipped to eastern markets, towns were established along the route of the railroad. In Kansas, first in Abilene, in 1867. An outbreak of cattle fever led to a quarantine line in the state, and the railhead moved further and further west, reaching Dodge City in 1876, roughly the years when fictional Marshal Dillon ruled the town.

From 1875 to 1886, some 5 million beeves were herded up the trail from Texas to Kansas railheads. In 1877 alone, Dodge City was the largest of the cattle-shipping boom towns, loading up and shipping out 500,000 head of cattle.

Route of the AT&SF Railway that got the beef to the slaughterhouses and meatpacking industry of Chicago

As Dodge City grew, and Kansas became more populated, the need for a fort on the Santa Fe Trail became less important, and by the end, when the fort closed in 1882, it was garrisoned by only about a dozen soldiers. The remaining buildings were later turned into a home for retired soldiers.

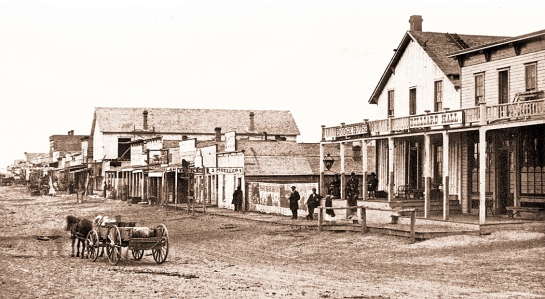

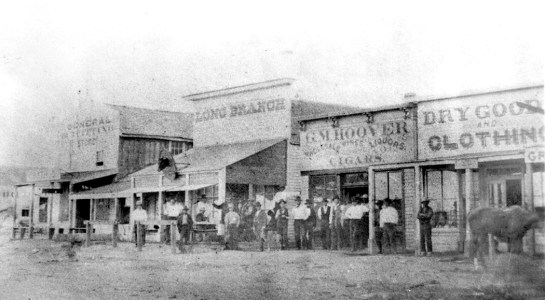

Dodge City, 1872

This was the milieu that the fictional Dodge City supposedly took place in.

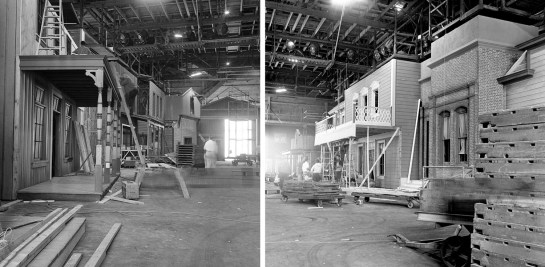

Gunsmoke remained on TV for 20 years and the town barely changed, despite having moved from its original outdoor location shooting to being filmed on fabricated sets in the studio.

Constructing Dodge City in studio for “Gunsmoke”

The actual town grew and changed continuously, beginning in 1871 with a population of 1 — as Henry Sitler built a sod house in the location five miles from Fort Dodge — to a population near of 1200 just five years later and to 1,763 by the 1890 census. TV’s Dodge City should have been filled with ongoing construction. The trains not only took cattle out of Dodge, but brought in supplies and lumber to build the town in a region mostly devoid of timber.

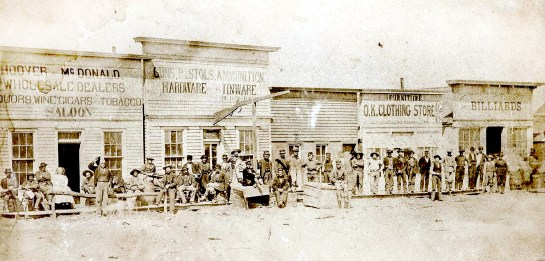

The town was incorporated and platted in 1872, and George Hoover moved to a wood building on Front Street to serve thirsty Fort Dodge soldiers, buffalo hunters and the increasing number of cattle herders.

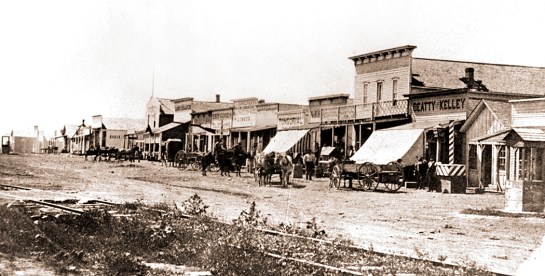

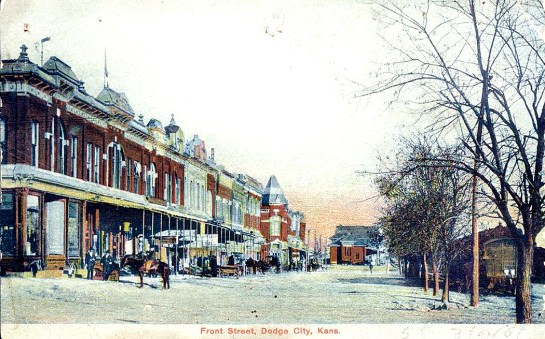

Front Street, Dodge City, 1872

Gunsmoke’s Dodge City was a standard-issue Western town, like those of so many other towns in other TV series and movies — a wide dirt street with wood-frame buildings on both sides.

The reality of Dodge City was that it was built alongside the Arkansas River, where the Santa Fe Trail paralleled the river. When the railroad came, it, too, followed the river. The town then grew on the far side of the tracks, leaving the town plan with the river to the south, the tracks to the north, and Front Street and the primary businesses in a single row on the north side of the street, as shown in this detail of the bird’s-eye view map, from 1882.

This was a common city plan, and can be found all across both the West and the South, wherever a town grew alongside railway tracks. Tracks; road; storefronts, in that order.

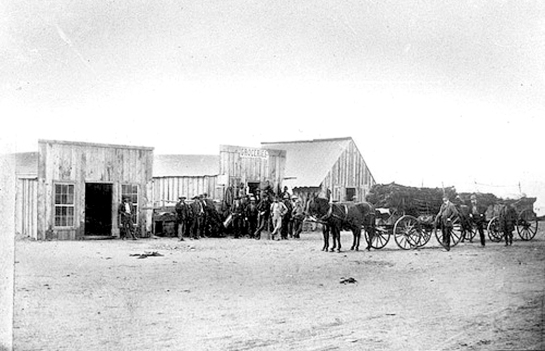

Winter 1872, Dodge City

Sidenote No. 2

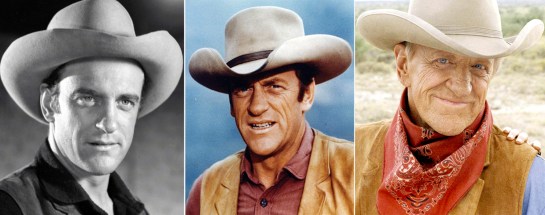

The constant growth of the town from 1871 to 1900 means that there is no single version of Dodge City to be had. It was always changing. Over the two decades of Matt Dillon’s TV tenure, the place barely changed a whit, although Dillon did. James Arness was 32 with a boyish face when the series began. When the series ended, he was in his 50s. Gunsmoke movies continued to be made, and by the time of the last, Gunsmoke: One Man’s Justice, from 1994, Arness was 71, which, if we insist on a concurrent timeline, puts the movie’s action into roughly 1914.

The TV show seems to remain static in time, other than the persistent aging of its inhabitants, but if we pretend the town aged as the actors did, the final episodes would have taken place in the 1890s. By then the cattle drives were long over, the town had settled into domesticity, and the six-guns and stetsons were relics of the past. The most common hat worn by men in Dodge city was a bowler.

Back to the main story

Dodge City, 1873

In the group of photos I collected, I found records of many of the town’s inhabitants, and they tell a story of Dodge City’s growth and character. I wanted to share a few of them. I purposely did not include information on several of the more mythic figures that are frequently dredged out to tell the tale. You can find all kinds of stories about Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, Dora Hand or Bat Masterson, and they have all been through the Dime Novel, Hollywood movie, TV series myth-making machine and many of their stories are questionable at best. Many conflicting versions abound.

So, I wanted to mention George Hoover, Chalk Beeson, Ben Hodges, Thomas McCarty, James “Dog” Kelley, Ormond Wright, and Squirrel Tooth Alice, among others, all of whom are central to Dodge City’s history.

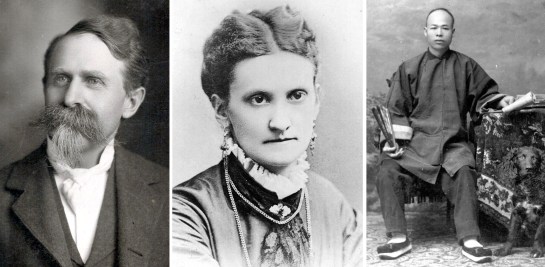

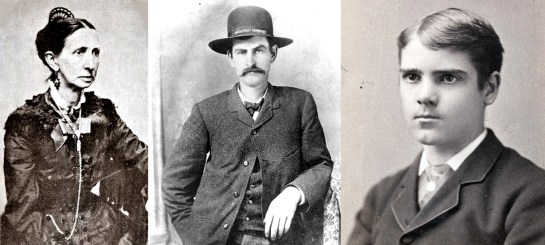

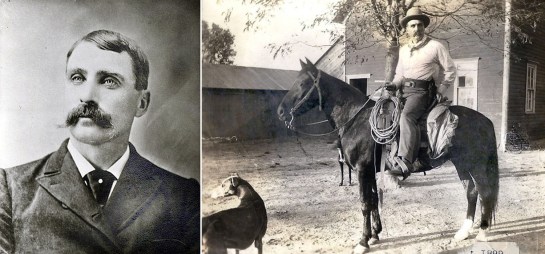

George Hoover and wife, Margaret

Hoover was the second person, after Henry Sitler, to settle on the site of what would become the town, in 1872 and set up a bar to serve travelers and the soldiers of Fort Dodge. He sold whisky by the ladle for 25 cents (equivalent value today: about $20.) At the time, alcohol was forbidden at Fort Dodge and for a radius of five miles, which is why Hoover’s tent-and-wood-plank bar was opened where it was and Dodge City took hold five miles from the fort.

Hoover became the town’s first elected mayor, reelected three times, became a state legislator, and, after many successful businesses, opened the town’s first bank. He died in 1914, a few months after his wife, Margaret, died. He said, according to the July 16, 1914, Dodge City Globe, “that he had but little desire to live longer, and declared that life had no more interest for him [after his wife’s death].”

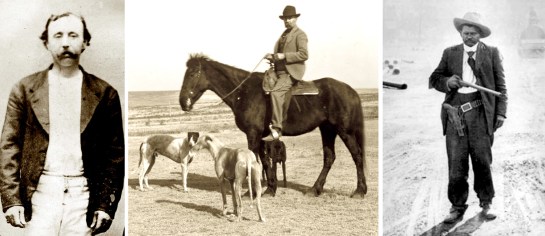

James Kelley, Kelley on horse, and Ben Hodges

British-born James Kelley was mayor of Dodge City from 1877 to 1881. He was part owner of the Beatty and Kelley Restaurant and kept a tamed black bear, named Teddy, behind the shop. Kelley had a white horse and often wore a white corduroy suit and kept a bunch of greyhounds, hence his nickname, “Dog” Kelley. His restaurant burned down in 1885 and he opened up the Kelley Opera House on the corner of Front Street and First Avenue. Kelley died in 1912, having spent his last years at the soldiers’ home at the former Fort Dodge.

Dodge City, 1878

Ben Hodges was half-Mexican, half Black and a cook’s helper on a cattle drive, who stopped in Dodge in 1872 and began a series of (unsuccessful) land-deal swindles and claims to wealth and nobility. He lived for years in a little shack on the south side of town, near the river and kept young boys fascinated with his tall tales. The town seems to have tolerated Ben as the “town character.” He was made an “Assistant Deputy” and allowed to carry a gun, minus the firing pin and his shoplifting of food from stores was accepted since, “he only took what he needed.”

When he died, in 1929, a collection was raised to buy him a plot in the elite Catholic cemetery rather than a pauper’s grave. According to one pall bearer, “We wanted him where they could keep an eye on him.”

Larry Deger and T.L. McCarty

Dodge City’s original Matt Dillon and Doc Adams were Marshal Lawrence Deger and Dr. Thomas McCarty. Deger was the first marshal of the town.

From 1871 till it was incorporated in 1875, Dodge City had no law officers, and things were quite chaotic, with a number of murders gone unaddressed until a vigilance committee was formed. Unfortunately, the committee soon became the source of violence and the Kansas governor appointed Charles Bassett sheriff of Ford County in an attempt to establish some order. It is estimated that between 1872 and 1876, some 70,875 gallons of whiskey were consumed in Dodge City, which is the equivalent of approximately or 4,536,000 individual shots — a lot for a town of about a thousand citizens.

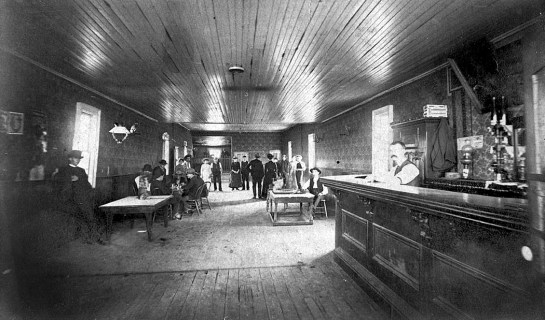

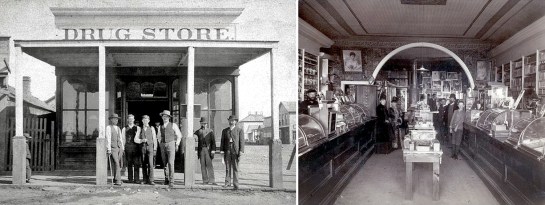

St. James Saloon, Dodge City

In 1875, Deger was appointed marshal by the town council (there is some confusion in the popular mind, as a U.S. marshal is a federal employee, while a city marshal is essentially the police chief and is hired by local government. However, in some locations, marshals were elected — it’s all quite confusing. Sheriffs are usually politicians, who are elected). Deger was a saloon keeper and took sides in a developing confrontation among townspeople between those who wanted a more open town to provide booze and professional women to cattle drivers, i.e. “good for business,” and those who wanted a quieter, more civilized town. Deger wanted peace.

What ensued in 1873 is sometimes called the Saloon Wars and sometimes the Dodge City Wars. Deger was by that time mayor and had laws passed establishing prohibition and outlawing prostitution. It was also suggested, for instance, “We should have an ordinance prohibiting the firing of guns within the city limits.” And, “We should have a law not allowing the riding of horses over sidewalks and into the saloons.”

In the course of these reforms, three “singers” at the Long Branch saloon were arrested, but none of the workers at other saloons were also nabbed. Favoritism was charged and the pro-business group, called “the gang,” hired a bunch of former lawmen as muscle for their side of the argument.

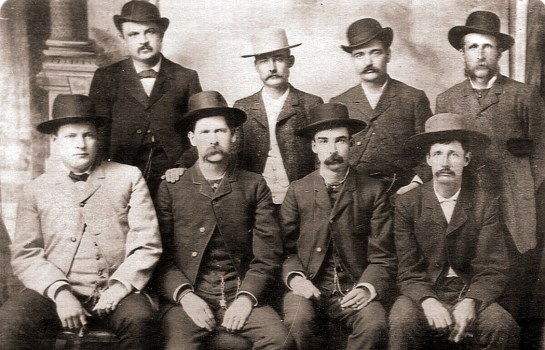

Dodge City Peace Commission

A famous photo of the group was made at the time, with (standing L-R: William Harris; Luke Short; Bat Masterson; William Petillon. And seated, L-R: Charlie Bassett, Wyatt Earp; Frank McLean; and Neil Brown.)

The sides stared each other down, but it was finally resolved without gunfire, and the Long Branch was allowed to reopen. But women in the profession were moved south of the railroad to the “wrong side of the tracks.”

Varieties Dance Hall, Dodge City

Deger married German-born Etta Engleman in 1883, and moved to Texas where he operated a lumber company. He died in 1924.

Thomas McCarty, his wife, Sarah, and Sing Lee

McCarty was the town’s first civilian doctor and Ford County’s first coroner. He and his wife, Sarah, arrived in Dodge City in 1872, on their way further west, but stayed in town. He operated his surgery and partnered in a drug store with Herman Fringer and later opened his own, called City Drug Store.

City Drug Store, 1877

McCarty’s son, Claude, was reputedly the first legitimate baby born in Dodge City, and later also became a doctor and with his father opened the McCarty Hospital in 1905, remodeling the old four-story Central Hotel.

The doctor’s household included a servant named Sing Lee, who wore the traditional Chinese queue.

Dr. Thomas McCarty died in 1930, ten years after his wife Sarah. His son lived until 1950.

Chalkley Beeson

Chalk Beeson came to Dodge in 1874 with his wife, Ida. Soon, he received the Billiard Hall Saloon as payment for a debt and renamed it the Saratoga, one of the few that didn’t employ prostitutes. Instead, he featured a five-piece band, with himself as leader on the fiddle. In 1877, the Dodge City Times wrote, “It is a rare treat to drop in at the Saratoga upon Mr. Beeson, and listen to his last and best musical combination. Mr. Beeson is a thorough lover of good music, and by his skillful selection of good performers … draws crowds of attentive listeners.”

Dodge City Cow-Boy Band, Beeson in center with fiddle

In 1884, he expanded his band to form the Dodge City Cow-Boy Band and toured, including an appearance in the inaugural parade of President Benjamin Harrison in 1889.

Beeson was later elected sheriff of Ford County and in 1903, elected to the state legislature. He died in 1912 when he was kicked by his horse.

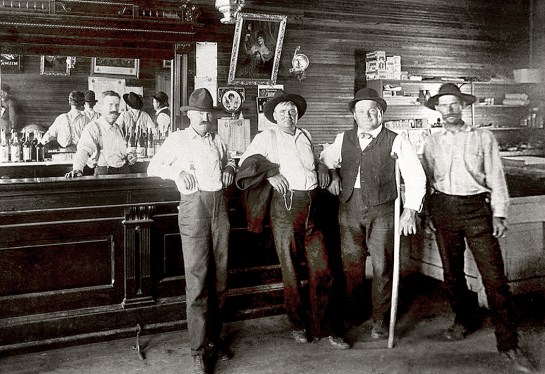

By the middle 1870s, there were a little over 1000 residents in Dodge City but 16 saloons. In addition to the Long Branch and the Saratoga were the Alamo, the Alhambra, the Crystal Palace, the Lone Star, the Oasis, Congress Hall and the Green Front. Some of them just one-room storefronts.

A reporter from the Hays City Sentinel wrote of Dodge City at the time, “The employment of many citizens is gambling. Her virtue is prostitution and her beverage is whisky.” On TV, the saloon girls share drinks with cowboys, but, as one writer put it, “Miss Kitty wasn’t selling chocolate bars.” We know the names of several of these hard-working women.

L-R: Sadie Ratzell; Squirrel Tooth Alice; Timberline; Mattie Blaylock

Sarah “Sadie” Ratzell was born in Philadelphia but grew up on a Kansas farm. When she was 18, she became a prostitute and lived with a Dodge City dance hall owner in the 1880s.

In July, 1881, she complained to then-Marshal Fred Singer about a man prowling around her home after dark. Singer found and shot 23-year-old Joseph McDonald hidden in a growth of sunflowers. A coroner’s inquest that followed notes “the latter raised his arm horizontally, as though in the act of firing. The marshal apprehended some danger from this movement, and not knowing whether the man had a pistol or not, raised his weapon and fired, the shot striking McDonald in the hand and passing into his right side, causing death in three hours.” Singer later resigned as marshal and opened saloon, which occupation he said was more financially rewarding.

Front Street with Long Branch Saloon, 1875

Squirrel Tooth Alice was born Mary Elizabeth Haley in 1855 in Texas. She was kidnapped by Comanches in 1864 and ransomed three years later. She ran away from home at 14 to become a dance-hall girl and prostitute. She hooked up with”Texas Billy” Thompson. In 1873, Thompson shot and killed the sheriff in Ellsworth, Kan., but escaped from jail and fled to Dodge City, where she took up her trade. Later the pair, by then married, moved to Colorado and later, Texas. She was known as Squirrel Tooth after a gap in her front teeth. She also kept pet prairie dogs on leash and collar. As Libby Thompson, she had nine children by several men, while running a brothel. She died in California in 1953 at the age of 97.

Rose Vastine was known as Timberline because she was 6”2’ and worked in Dodge City in the 1870s. According to one account, she was suicidal, and while later living in Creede, Colo., shot herself six times, but lived. “She made yet another attempt to shoot herself in the chest in 1893. ‘Medical attendants were at once summoned and the would-be suicide is in a fair way to recovery,’ said the newspaper.” Little else is known.

Dodge City, 1879

Celia Ann Blaylock was born in Iowa in 1850. When she was 18, she ran away from home and found her way, as Mattie Blaylock, to Dodge City, where she became a prostitute. In 1876, she took up with city deputy marshal Wyatt Earp and for six years lived as his common-law wife while maintaining her profession. She suffered from extreme migraines and became addicted to laudanum as a pain killer. She left Dodge City with him in 1879, going to New Mexico, and then to Tombstone, Ariz. Eventually Earp left her, and in 1888, she died from an overdose, ruled by the coroner as “suicide by opium poisoning.” She was 38.

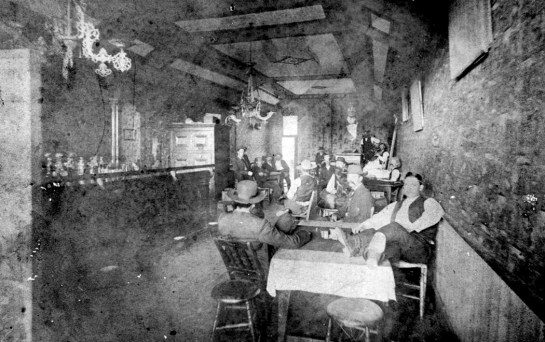

Interior, Long Branch Saloon

The Long Branch has become the most famous, although there never was a Miss Kitty. It was established in 1874 and named for its owner’s hometown of Long Branch, N.J. It passed through several hands and in 1878, Beeson bought a share in it. He sold his portion in 1883 to Luke Short.

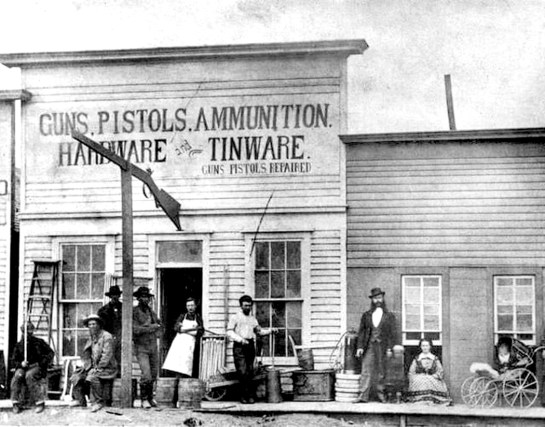

Zimmerman’s hardware store

Two years later, it burned down in a fire that destroyed much of Front Street, taking out in addition, Dog Kelley’s Opera House, Charles Heinz’s Delmonico restaurant, the York, Parker, Draper Mercantile Company, F.C. Zimmermann’s hardware store and even the first brick building in town, Robert Wright’s store, which held out long enough to retrieve a good deal of his merchandise before the building went. But, as the newspaper reported, “Some awful good whiskey was allowed to burn up.”

That fire, and a second, smaller one a month later, led the city council to establish a fire department and a city water works, with fire hydrants around the city.

Robert M. Wright and his book

There are many more citizens of Dodge back then, and I can’t include them all. One early resident (and later mayor — they all seem to have taken turns as mayor) was Robert Wright, who, in his old age, wrote a book called, Dodge City, the Cowboy Capital and the Great Southwest in The Days of The Wild Indian, the Buffalo, the Cowboy, Dance Halls, Gambling Halls, and Bad Men, published in 1913. It is loaded with familiar stories of the early times in Kansas, but also argues that it wasn’t as bad as all that. He tries to put a clean face on the popular image. (I have read it; let’s just say, Wright was not a graceful writer — it’s a tough slog). Wright dies two years after his book was published.

L-R: Margaret Walker; Dave Mather; Rev. Ormond Wright

Among the many people I have had to leave out of this blog entry are Margaret Walker, the town’s first schoolteacher; “Mysterious Dave” Mather, who owned the Opera House Saloon and was the survivor of one of the more famous gunfights in town; Rev. Ormond Wright, who presided over the first church built in Dodge, a non-denominational worship.

Dodge City, 1887, with Arkansas River

There were enough documented personalities from the early years of Dodge City, that a TV series could have been made without resorting to the fictions of Matt, Doc, and Kitty. (I mean no slight on Gunsmoke, which, especially in its early years did truly attempt to be more faithful to the spirit, if not the fact of its times, and was often extremely well written.)

Dodge City, 1890s

Dodge City went from tents and sod to wood frame buildings and to multi-story brick in a little over ten years, in the process building institutions, electing a town council and mayor, and hiring a police force, so that, when the cattle industry largely disappeared in the 1880s, it was prepared to be a self-sustaining community. The real town was a dynamic entity; on TV, it was just a stage set.

Click any image to enlarge