Over the past few decades, the programming at our symphony concerts has become routine and predictable. I’m certainly not the only one to notice this, but almost every program follows one of two patterns: Either overture, concerto, intermission, symphony; or, overture, smaller symphony (perhaps Mozart), intermission and then big concerto (like Rachmaninoff Third). Over and over, this pattern holds, which leaves a lot of great music never played. Programming has become stultified.

And even the list of symphonies and concertos that do regularly make the cut has shrunk to a roster of “fan favorites.” When was the last time you heard a live performance of, say, the Bruckner Sixth or the Joachim Violin Concerto? They used to be played — they show up in old programs.

Of course, you can find recordings of everything. If you want an Atterberg symphony, there are multiple CDs on Amazon. But go to Symphony Hall and you will wait a very long time and grow your beard very gray.

There is a particular class of music that has suffered by this development: those shorter, once-familiar staples of both concerts and Looney-Tunes animations. They used to be a regular part of symphony concerts but now are seen as “not serious enough” for well-bred audiences seeking morally and spiritually uplifting artistic experiences. That is too bad, because a lot of this music is absolutely brilliant, and what is more everyone loves it, to the point of being able to whistle the tunes.

The conductor Thomas Beecham once said, “Composers should write tunes that chauffeurs and errand boys can whistle.” And, “Music first and last should sound well, should allure and enchant the ear. Never mind the inner significance.”

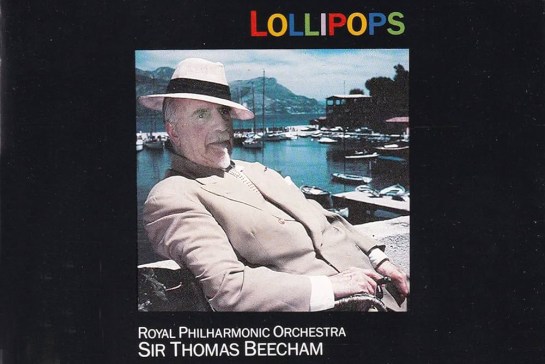

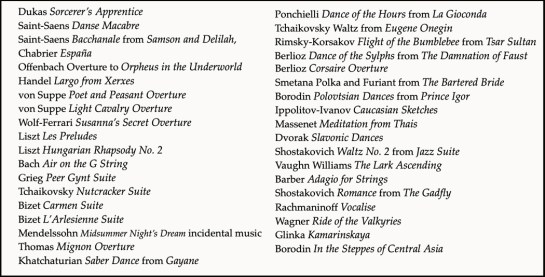

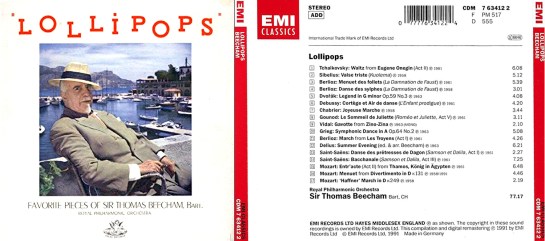

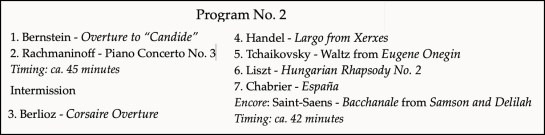

Beecham was one of the greatest conductors of the 20th Century, and could lead a great performance of a Beethoven symphony, so he wasn’t a mere light-weight. But he regularly included in his programs what he called “lollipops,” which are the smaller, brighter pieces that get short shrift nowadays, pieces such as Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite or Handel’s Largo from Xerxes. There were excerpts from longer pieces, and shorter concerted works for piano or violin soloists that weren’t full-lengths concertos. When was the last time you heard a live performance of Saint-Saëns’ Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso? It is a brilliant show piece for a virtuoso violinist.

There are several registers of concert music. At the top sits the top-hat and tails music of Brahms and Beethoven. At the lower end are the Pops concerts with their orchestrated show tunes and movie scores. Arthur Fiedler ruled that kingdom, and included lightweight but catchy music by Leroy Anderson or Albert Ketèlbey. In between there are the New Years concerts of Strauss waltzes and polkas. Fiedler often included some of the more serious music in his Boston Pops programs, but those works have all mostly disappeared from Carnegie or Severance halls.

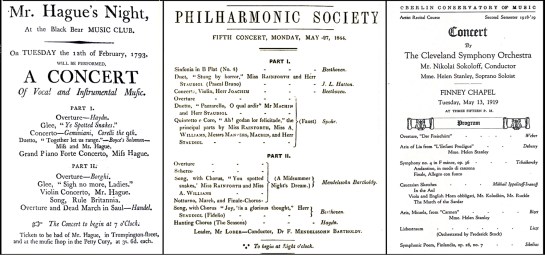

If you look at symphony programs from a hundred years ago, or two hundred, you find these shorter pieces sprinkled in among the symphonies and tone poems, with no apologies made for their simple popularity. Concerts, after all, are meant to be entertainment.

In Haydn’s day, when middle class supplanted the aristocracy as the prime audience for concert music, his programs included singers, soloists, maybe a chorus and a symphony (then called an “Overture”), which often had its movements split up, with bits of song or violin music in between. It was a varied experience, more like a music hall show than a serious artistic event. They were meant to be popular; meant to sell tickets.

Even in the earlier 20th century, concerts featured both heavy and light classics. But the helium has fizzled out of the balloon.

In the LP era, Beecham released several records made up solely of these lighter, brighter gems, in albums titled “Lollipops.”

They were once the common cultural inheritance of American and European culture. They made up the bulk of recordings from the first half of the 20th century, when 78 rpm records could contain only about 5 minutes on a side, which made recordings of entire symphonies or complete operas both exorbitantly expensive and with 20 or 30 sides on 12-inch discs, really, really heavy to haul around. And so, shorter, popular pieces, like the encores of violinist Fritz Kreisler, became best sellers. I am old enough to have once owned piles of 78 rpm classical music recordings.

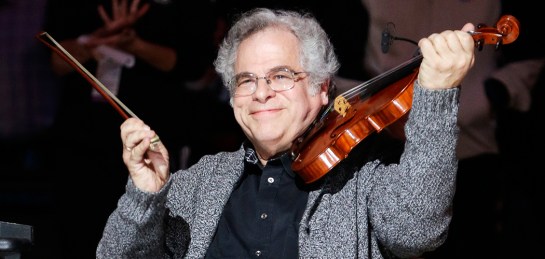

A last vestige of that can be found in the recitals of Itzhak Perlman. I’ve seen him several times and it’s always the same. A warm-up sonata, played very well, but nothing special, followed by a major piece performed to blow your socks off (I heard him do the Strauss Violin Sonata — a piece not thought of as among Strauss’ best work — and make it sound like the greatest thing every written for the fiddle); then, after intermission, he spends the last half of the recital playing old short pieces, sometimes requests, and tells corny jokes in between — real Borscht-Belt material. And so, we hear Hora Staccato and Liebesfreud, pieces otherwise consigned to history.

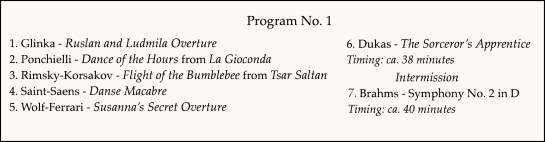

But why couldn’t symphony orchestras do something similar, make half a program of shorter tchochkes and tuneful shorter pieces. Perhaps load them up in the first half of a concert and follow that with a second-half major symphony.

Or, do it like Perlman and leave the audience warm and fuzzy as they leave the auditorium humming the old familiar tunes of Offenbach or Ferde Grofé.

Somehow, symphony programs need to be decongested, and let breathe more freely. And there is all this wonderful music that is kept in storage that should be pulled out and given some sunshine.

Click on lists for improved readability