Intro: What We Get Wrong

The 1984 movie, Amadeus, won eight Oscars and has been seen by millions of people. It was an excellent film, but it lied through its teeth. Mozart was not an arrested-development adolescent potty mouth. And Antonio Salieri never tried to kill him.

Poor Mozart, he has had his life twisted over the centuries to illustrate cultural trends, and those trends have changed over those years.

The 19th century first saw him as old fashioned, then he became a proto-Romantic, with his life deeply mythologized. The 20th century first saw him as a kind of porcelain doll, and after WWII, saw him as a polite precursor to Beethoven. In the 21st century, he has been the victim of countless historical-performance strictures that leave his music in a kind of inexpressive jog-trot strait-jacket.

The man sometimes considered the greatest composer of all time has been so mauled over by his biographers, fans and later writers and filmmakers that the legend has taken over from the fact.

So, the plot of Amadeus is only one of a myriad of distortions, legends, myths and factifications. The truth, as usual, is more interesting.

What are some of the worst Mozart myths?

— Mozart began writing masterpieces before he turned 10.

* Yes, he wrote music beginning before he turned six. But some of that music was arrangements of other composers’ work, some may have been outlined by his father for the boy to complete, and none of them are masterpieces, or noteworthy, other than for them to have been jotted down by one so young. The early works are generic. They get played, when they are played at all, simply because they have Mozart’s name attached.

— Mozart was buried in a pauper’s grave.

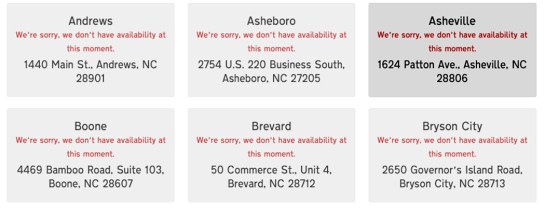

* Although it’s often said he died so poor he was buried in a pauper’s grave, the fact is Viennese law required anyone other than an aristocrat to be buried in a common grave, after a funeral service at the church. It was a reaction to recent outbreaks of plague in the country. And Mozart wasn’t poor. He lived quite well, although, working in what we would now call a “gig economy,” he had his income ups and down.

But, over his last year, he earned 10,000 florins when an average laborer averaged 25 florins a year. It put him in the top 5 percent of the population of Vienna, according to H.C. Robbins Landon, author of 1791: Mozart’s Last Year. The man was no pauper, and his music was hugely popular, not only in Vienna, but across Europe. And when he died, he had a hit on his hands: The Magic Flute. He left his widow reasonably comfortable.

— Mozart wrote his music spontaneously, without effort.

* Mozart’s facility with music was remarkable, but there are plenty of sketches and studies for his music. The pieces without such preliminary work most likely had them at one time, but they don’t survive. His widow, Constanze, burned most of the sketches, not thinking that fragments had any value. Mozart even writes to his father about doing such preliminary work.

In 1787, he told the conductor of his opera, Don Giovanni, “It is a mistake to think that the practice of my art has become easy to me. I assure you, dear friend, no one has given so much care to the study of composition as I.”

— His middle name was Amadeus.

* He was baptized as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart but his parents called him Wolfgang Gottlieb (Gottlieb being German for Theophilus). He usually signed his name Wolfgang Amadé. It was only after his death that people began regularly calling him Wolfgang Amadeus, which is a Latinized form of Gottlieb.

— His music is simple, direct, easy to listen to, easy to perform.

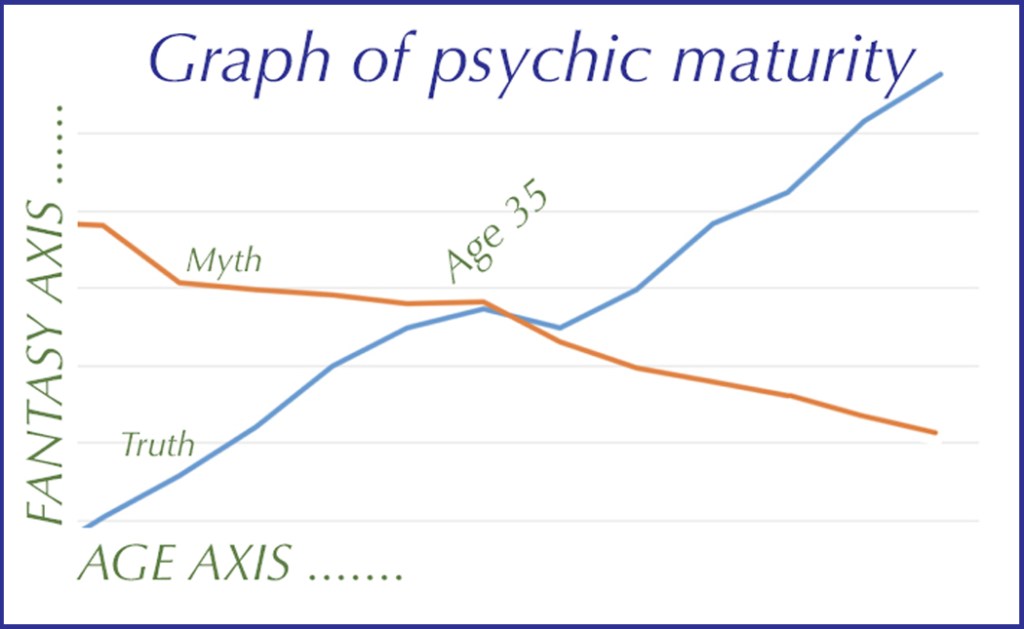

* And at the time of his death in 1791, at a mere 35 years old, his music was considered difficult to play and demanded careful listening. Mozart asked a lot. When the progressive Emperor Joseph II famously told Mozart his music had “too many notes, my dear Mozart. Too many notes.” he wasn’t being an ignoramus; he was reflecting the general taste of his times. To understand this, we need to place him in context.

Some Context: The Classical Era

Something else we get wrong: It is usually said that Mozart and his contemporary Joseph Haydn wrote in the classical style, as if such a thing existed, and all they did was follow the rules. That’s got it completely backasswards. They didn’t write in the classical style; they invented the classical style. They were making it up as they went along.

Music history is taught as consisting of succeeding eras. The Renaissance gave way to the Baroque, which led to the Classical era and on to the Romantic, to Modernism and currently, Postmodernism. As if they were clearly defined and separate. And it is true that after about 1740 or so the heavily contrapuntal Baroque lost its hold on the ears of its listeners. They wanted something simpler, clearer, more charming and that wouldn’t be so serious. All those fugues and counterpoint of what was called “the learned style” gave way to homophony — that is, tuneful melodies and supporting harmonies. Something you could hum along with: Simpler and more direct.

This is sometimes called the Style Galant; it followed the Baroque the way Rococo followed in the visual arts. Composers such as J.C. Bach, Johann Joachim Quantz, Johann Stamitz, or Domenico Alberti published torrents of light, catchy three-movement sinfonias and bright concertos, to say nothing of keyboard music to be played after dinner by the daughters of aspiring middle-class burghers. I’m grossly simplifying this, but the outlines are true.

This is the kind of music both Mozart and his older contemporary Haydn produced in their younger days. Mozart wrote more than 20 symphonies in this popular style before the age of 17 and if they still get played it is because, again, they have Mozart’s name on them, and also, because they are full of great tunes. Mozart always wrote great tunes.

Haydn had his own orchestra, paid for by his boss, Prince Nikolaus Esterhaza, a ridiculously wealthy Hungarian nobleman, who loved music. Hidden away at the prince’s countryside palace in Esterhazy for some 30 years, Haydn developed on his own, inventing new ways to delight and surprise an educated audience who learned and grew along with the composer. The palace was far from Vienna. Haydn said, “I was cut off from the world. There was no one to confuse or torment me, and I was forced to become original.”

He basically invented the modern form of the symphony and the string quartet.

Prince-Archbishop Colloredo

Mozart, however, was truly cosmopolitan and after freeing himself from the employment of Salzburg’s prince-archbishop Colloredo, earned his crust as a freelancer in what was becoming a “gig” economy, living from commission to commission, and from concert to concert and opera to opera.

He learned a lot from Haydn, and joined him in making his music increasingly more complex than the usual run of gallantries. They added back counterpoint to their works, increased chromatic and harmonic subtleties. Mozart’s music, for instance, is always more complex than it sounds.

Mozart asked his musicians to do more than did other composers: to play higher, lower, more quickly; to play notes unfamiliar to their instruments or voices; to attempt unusual phrasings and colorations.

At the end of Act I in Don Giovanni, three bands play onstage at the same time, performing different music in three different rhythms, but entwining their harmonies so they mesh perfectly in a tour de force of compositional cleverness.

His music sounds simple and perfect and symmetrical, but you look at the phrase structure and it’s highly irregular. Normally, you expect 4- and 8-bar phrases, but you take a look at one of Mozart’s late scores and you see phrases of 4, 5, 3, 7, 8, 6 — but you would never guess it was so irregular just from hearing it. It always sounds smooth.

And although the surface of the music is always velvety and seductive, it’s frequently chromatic, introducing notes that shouldn’t belong. Even so graceful and simple a tune as the trio from the minuet in the popular Eine kleine nachtmusik manages to use 11 of the 12 notes in the chromatic scale. It verges on Schoenberg, though it sounds as simple as a nursery rhyme.

While Haydn’s metier was primarily instrumental music, Mozart shone in vocal music, and especially opera, where he brought psychological complexity to what is sung.

Mozart as Shakespeare

Mozart was the Shakespeare of music. No composer ever displayed a wider sympathy for the human condition or a greater breadth of musical style. At the bottom of his music is a profound humanism, which is all the more obvious in his best operas — The Marriage of Figaro, Così fan tutte, The Magic Flute and Don Giovanni.

Of all the great composers, Mozart also is the easiest to love. Bach may be more sublime, Haydn wittier, Beethoven more in-your-face and Schubert one of the few who could write melody to equal Mozart, but Mozart remains the most accessible. He speaks directly to us, because he is the most humane.

That quality underlies all his major operas: His plots are filled with three-dimensional people, not the stock characters of most other operas. No hero is flawless, no villain unredeemable.

The miracle is that it isn’t just the libretti that convey this complexity, but the music itself. It gives us the subtle psychological undertow.

Mozart understood all of his characters well. None of them is tossed off as inconsequential. He imbues each character with definitive musical qualities.

So that Don Giovanni’s ebullient life force is expressed in his headlong “Champagne Aria,” with barely a moment to inhale. Or the Queen of Night’s rage in Magic Flute, when she launches into Baroque arabesques and arpeggios in her showpiece “The vengeance of hell boils in my heart.”

Even in Figaro: Has adolescent horniness ever been better expressed than the “amorous butterfly” take the hero sings about the love-struck Cherubino?

All these characterizations are built on the composer’s willingness to accept without judgment everything that is human. Perhaps that’s why nobody ever wrote forgiveness better than Mozart.

Each of his major operas has a scene of forgiveness in it, and it’s usually the turning point of the action, when a character recognizes the frailty of human nature. Such forgiveness is not bestowed from a feeling of superiority but from shared compassion.

It’s not that we believe the Count in Figaro will now be faithful to the wife who forgave him, but that we know she will always forgive him, because this is what it means to accept the human condition.

But the particular mood Mozart raises in such moments also is carried into his purely instrumental music: The slow movement of his Piano Concerto No. 18 is the echo of such a moment in Figaro. It sighs, and we sigh with it.

Such genius, whether Shakespeare or Mozart, can’t be explained. You just accept that it is.

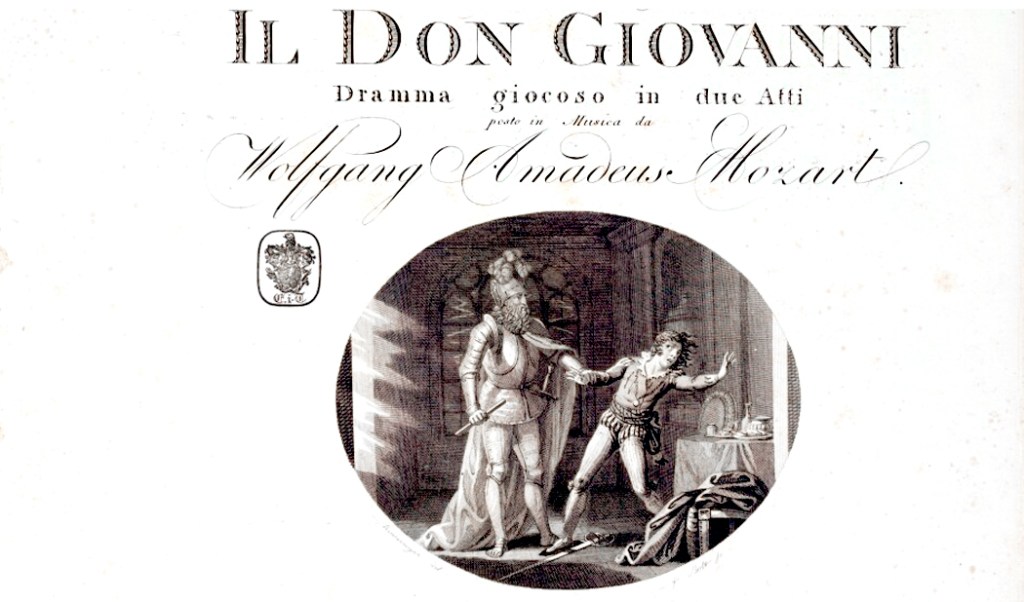

Don Giovanni

Mozart’s Don Giovanni has been called the perfect opera. It ingeniously balances comedy and drama, music and theater, the aristocracy and the peasantry, the past and the future.

It was first performed in 1787 in Prague, where the composer was a musical superstar, and told the story of the seducer Don Juan (Don Giovanni in Italian).

The story is simple in outline: After he kills the outraged father of one of his amorous conquests, Don Giovanni is tracked down by his victims. When he hides in a cemetery, the statue of the dead father miraculously asks him to dinner and, later, when the don shows up, the statue drags him to his judgment in hell.

But Mozart and his librettist, Lorenzo da Ponte, took what was a traditional story of sin and punishment and made it into a paean to the life force. Technically, Don Giovanni is still the villain, but Mozart and da Ponte made him such an engaging and vital presence that in the end, when he refuses to repent, despite the demons that surround him and the brimstone that burns, he actually rises to the heroic. Is he hero or villain? Or both.

This is where the Classic past meets the Romantic future: The cautionary moral tale of the past turns into the Byronic hero of the upcoming 19th century, and Mozart is in the avant-garde.

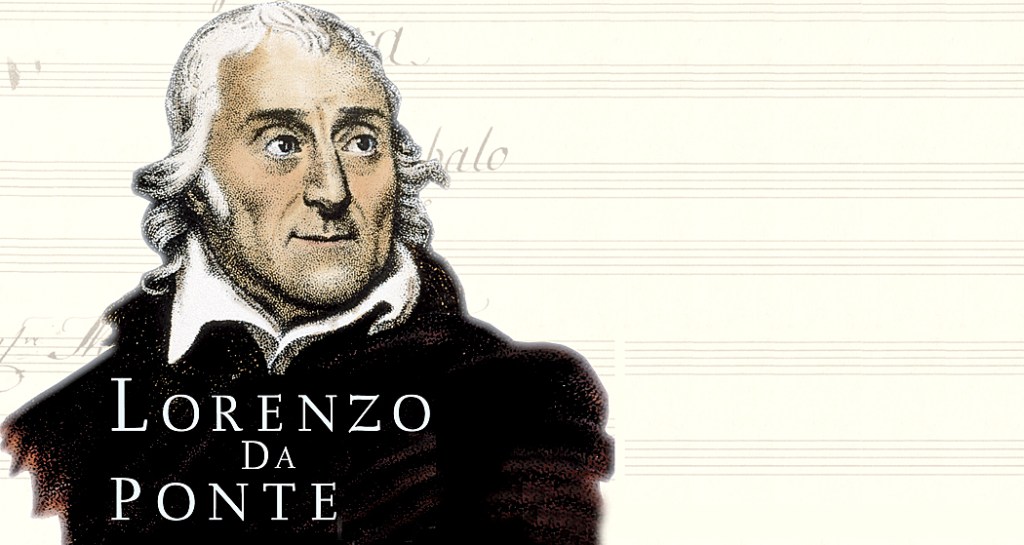

Digression I: Rake with a Quill Pen

Opera is a collaborative art. Mozart’s music is great, but so was the libretto written by Lorenzo da Ponte. Da Ponte was born a Jew in Venice in 1749, was ordained a priest and opened a brothel with his mistress, where he entertained the clients by playing violin in his priest’s vestments. He was the perfect choice to write the libretto for Mozart’s dramma giocosa, Il dissoluto punito o sia Il Don Giovanni (“The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni”).

Da Ponte was a friend of the infamous seducer Casanova and was forced to flee Venice after a trial for sedition, settling in Vienna, where he wangled a position from Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor. When he was asked how many plays he had written, he answered, “None, sire,” to which the emperor replied, “Good, then we’ll have a virgin muse.”

He wrote libretti for dozens of lesser operas by lesser composers, such as Antonio Salieri, before landing a job writing — or rather rewriting — Beaumarchais’ popular play The Marriage of Figaro as a libretto for Mozart. He also wrote Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte before being shown out of the city by the police.

Da Ponte’s post-Mozart life is hardly less interesting. After marrying (quite a trick for a priest), he moved to the United States, where he failed as a grocer, became friends with Clement Moore (reputed author of ’Twas the Night Before Christmas), who helped him gain a faculty post at Columbia College (now Columbia University), where he was the first faculty member to have been born a Jew.

In 1828, he became an American citizen, died 10 years later, had a grand funeral at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

The Pop Star

Mozart’s time was the late 18th century. He was born in Salzburg, Austria, in 1756 and was one of the great child prodigies of all time, picking up the violin when he was four and composing by the time he was five. His first opera was written when he was 12.

He was trooped across Europe by his father, playing for the amazed aristocracy and gathering gifts of money and jewels.

He outgrew his boyhood cuteness but grew to be one of the most prodigious composers of all time: He wrote 22 operas, 50 or so symphonies, 27 piano concertos, 23 string quartets, 17 settings of the Roman Catholic Mass. His complete works take up 170 CDs in one current set.

And he became enormously popular.

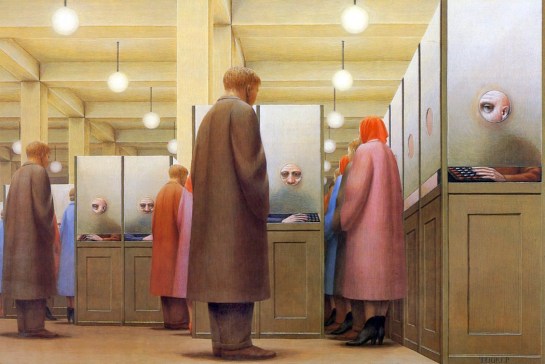

Mozart was the pop artist of the time. People wanted to play and hear that music so much, they transcribed the music for all kinds of ensembles. Every town had a wind band and they played arrangements. Every little village in Belgium or Bavaria could play arias from the latest Mozart opera, the way halftime marching bands now play show tunes.

Mozart makes fun of this phenomenon in the finale of Don Giovanni, when the don has a dinner in his castle, with a band playing the latest hits from operas, including “amorous butterfly” from Figaro.

He dismisses it: “I’ve heard this piece too much, he says. We laugh because it shows Mozart could take a joke. And that only makes him more human.

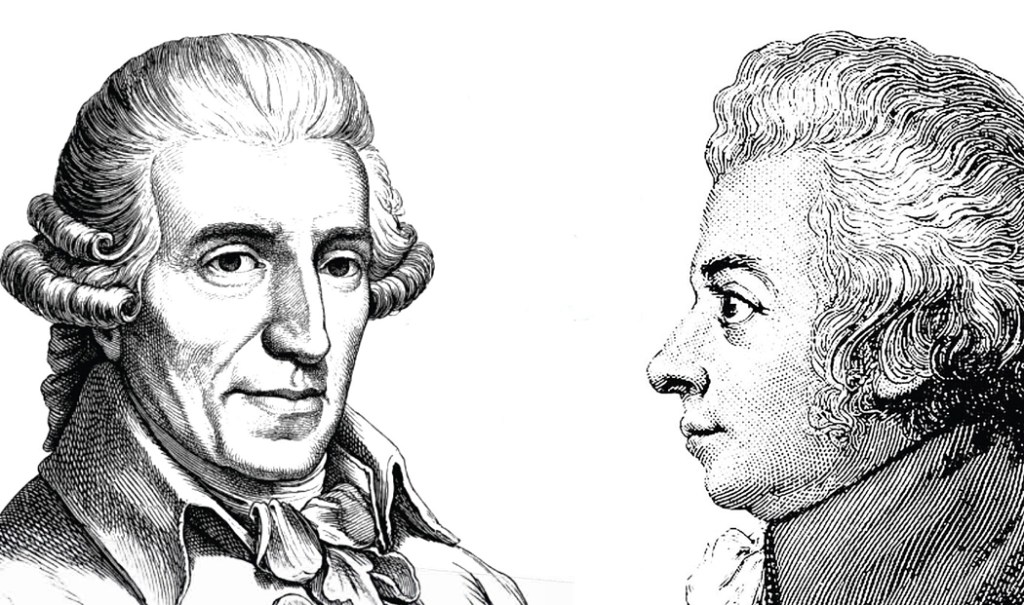

Digression II: Mozart and Haydn

The era from about 1770 to 1810 is called “Classical.” It’s the age of music defined by two names: Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Mozart.

They were the twin colossuses of the time: one witty and bright, the other deeper and more melodious.

But the two men were very different. Haydn brighter and more brittle sounding, with an emphasis on what the 18th century valued as wit, making in-jokes in his symphonies and working simple themes into complex textural patterns that his audience recognized with pleasure — they got the joke.

Mozart’s music is darker, more chromatic, with a more blended sound, and he focused his attention on grace and style.

If Haydn is the brain of 18th-century music, Mozart is the heart.

They valued each other above anyone else and recognized each other’s genius. Mozart learned more from Haydn than from any other source. Haydn said Mozart was the greatest composer alive.

To many, Haydn and Mozart sound alike. They are very different but shared a musical language. So, how do you tell them apart?

One wise old professor explained his simple test: “If you can remember the tune after it is over, it was Mozart.”

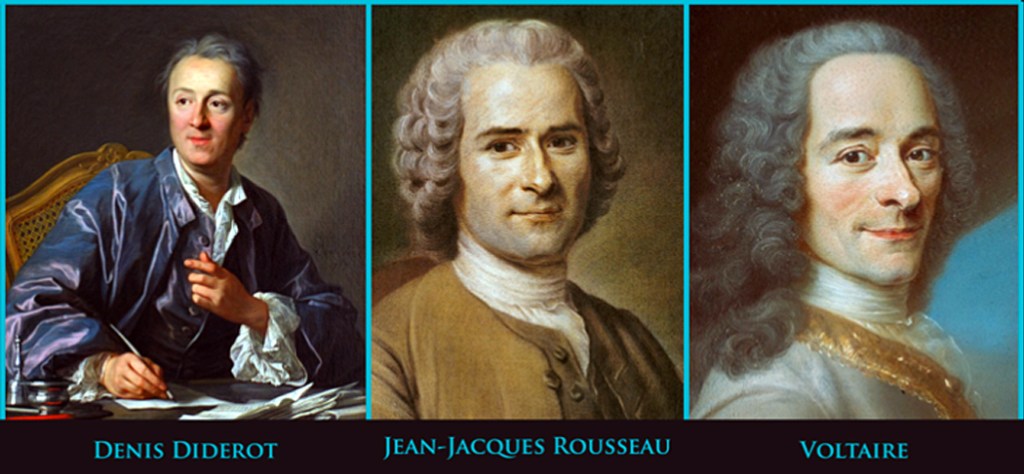

Reason and order

The 18th Century is called “The Age of Reason,” although sometimes I think it may be said ironically, since, after all, it was also the age of Rousseau, the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror. But the overall tenor of the era was one of rationality and balance, of a just God in his heaven keeping proportionality in everything human and cosmic.

In German-speaking lands, it was the Aufklärung, the “clearing up,” and prompted enlightened rulers, such as Joseph II in Vienna, to downplay religious fervor, mindful of the chaos of the Thirty-Years War, and promote scientific enquiry and philosophy. Coffeehouses rose filled with debate and Freemasonry became fashionable. Mozart became a Freemason, and his final opera, The Magic Flute, was a Masonic allegory, of sorts.

There were certainly many points of view, but the general sense was one of moderation in all things. Don’t go overboard. Keep an even keel. Music followed suit: nothing too extreme, but nothing too simple-minded, either. It was a perfect walk between opposites.

And the major musical innovation of the era was the rise of the Sonata-Allegro form. It was the primary organizing principle for Haydn and Mozart and held sway in various permutations for the next century and a half. It is usually taught in a technical way: first theme in the home key, second theme in the dominant, followed by a development section and rounded off with a recapitulation of the two primary themes, but now both in the home key. But that is not why the form became so dominant. That is like describing an angel as having wings and white robes, without ever noting it is a messenger from God.

The point of the sonata form was to establish an order, in terms of recognizable melodies, to then disrupt the order by breaking up the tunes into bits, rearranging them, and playing those pieces in a hodge-podge of shifting key-centers, leaving the listener with no firm ground to stand upon, and then reasserting clear order once again, so the universe is set right. Order – disorder – order reaffirmed.

Once you understand the metaphor of the sonata form, you will never again be hoodwinked by the academic palaver. The music is about the primacy of providential order.

This is a metaphor that has provided the foundation of much of art. Shakespeare’s histories and tragedies are all about disturbed natural order that has to be set right. Opera plots are almost all about illegitimate threats to the way things are supposed to be. It is the mega “A-B-A” of countless poems and novels.

The form made such satisfying intellectual and emotional sense that it ruled western instrumental music almost until now. Those composers who didn’t write sonata form wrote in protest to it. Take a side. It was that influential.

L’Envoi

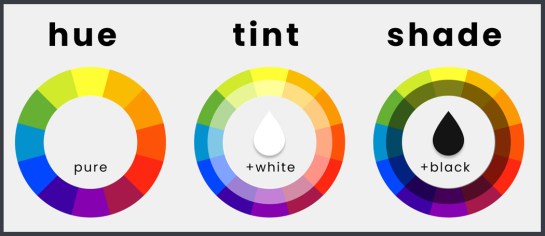

It is nearly impossible to write words about music. One tends to write impressionistically and metaphorically about what one hears, but such language become like trying to describe color to a blind person.

The result is that when most people talk about their favorite popular music, they talk about the lyrics. The music is barely mentioned. In fact, most popular music contains scant little actual music at all: just a few familiar chord changes under a meandering set of melodic intervals. You may mention the beat, but that, too, tends to drone on monotonously through the song.

You could, if you wanted to, talk about the music, but it would take specialist vocabulary that would convey almost nothing to the lay reader: “The composer used the Neapolitan relationship to modulate from B-minor to A-flat major while dividing the treble from the bass line in hemiola.” There, does that mean anything to you? Two against three?

One reads scores rather than text to understand what is going on, but even that does not really tell you what you are hearing, only how it was done.

And so, when writing about Mozart, almost everyone falls immediately into biography. We can tell you fascinating things about his family, his sister, he relationship with his patrons or the order in which his symphonies were composed.

But the ear can hear how, in sonata form, we hit the comfort of the home key as the recapitulation calms down the churn of the development. It is something instantly felt through the ear — if you are paying attention. But how to write about that in the Jupiter Symphony or the K. 545 piano sonata comes a cropper. Just listen. It’s obvious.

One can say that Mozart blends his wind instruments while Haydn tends to keep his winds distinct. It is true, but you have to hear it to understand. Mozart’s recapitulations are usually a return to order, while Beethoven uses his recaps (in his mature work) to take the music to a new place, a “new normal” that means we have moved through the development from Point A to Point B. Mozart’s melodies tend to be step-wise, as a human voice might sing, while Haydn often jumps around because fingers on a keyboard can do so.

These are swooping generalities, and there are plenty of exceptions, but they are attempts to write about the music rather than the historiography.

The only recommendation is to listen to more music, lots of it, and absorb what you can, so you can distinguish the difference between a sonata form and a rondo, between an English horn and a bassoon in its upper register. Hear it and pile it into your trove of experience. It is the sounds that are made that is the music. Words get in the way.

And pay attention. Music isn’t a warm bath you slide comfortably into, but a conversation the composer is having with you.