Some years ago, there was an unusual installation at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art. It was a 34-minute video by Mungo Thompson titled The American Desert (for Chuck Jones) and consisted of altered clips from old Warner Brothers Roadrunner cartoons, with the protagonists filtered out, leaving a series of edited backdrops of the American Southwest, with mesas, buttes, canyons and cliffs.

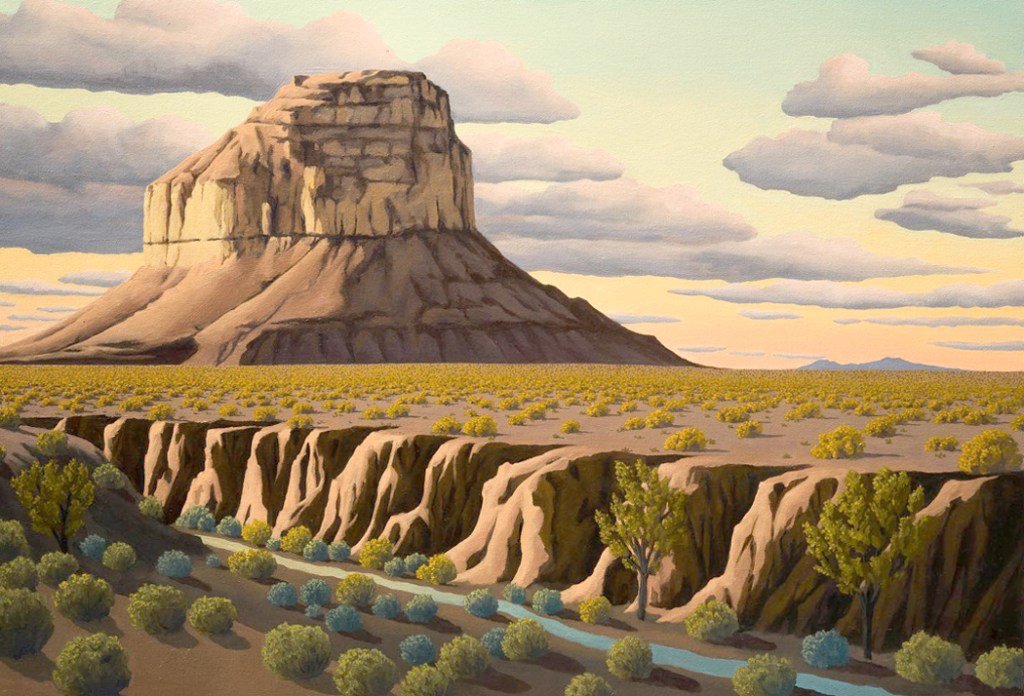

Screen grabs of Mungo Thompson’s “The American Desert (for Chuck Jones)

The video loop (it played continuously) showed me the landscape I knew so well, but translated into cartoon visuals, with all the shapes, colors and weirdness I loved from the Colorado Plateau — Monument Valley, Canyonlands National Park, Capitol Reef NP and Arches NP, the Navajo and Hopi reservations — simplified and turned into theatrical backdrops.

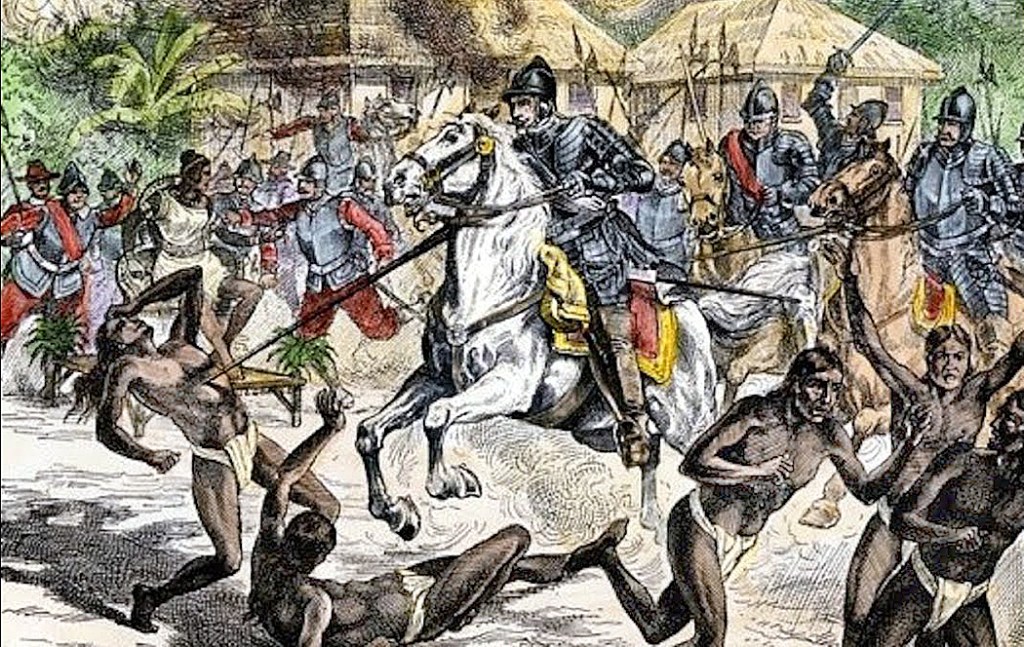

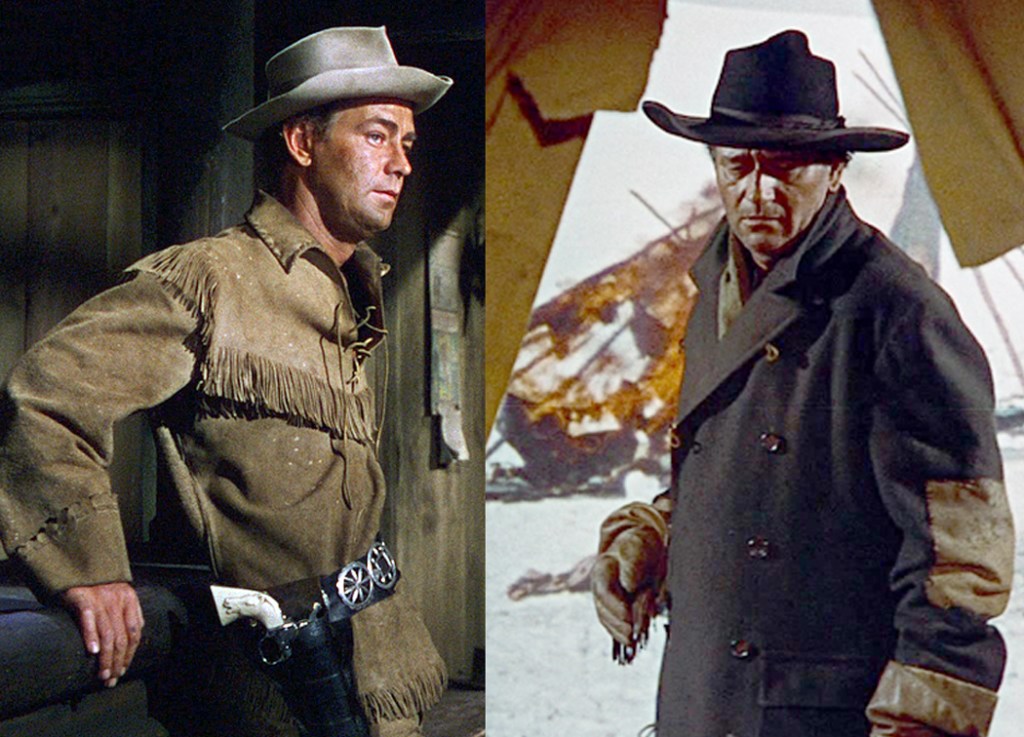

That region has served its term many times over more than a century, as backdrop for drama, from early silent Westerns (The Vanishing American, 1925), through classic John Ford films (beginning with Stagecoach, 1939), and most recently in the Coen Brothers’ Ballad of Buster Scruggs. The Southwest is photogenic, if nothing else.

But the Warner Bros.-Chuck Jones animation presented a stripped-down, diagrammatic version of the landscape that gave us the essentials only — the rocks, cactus, roads and precipices.

Warner Brothers, already famous for its Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck cartoons, tried something new in 1949, with the first of its series of Roadrunner cartoons, Fast and Furry-ous, with characters created by writer Michael Maltese and drawn by Chuck Jones.

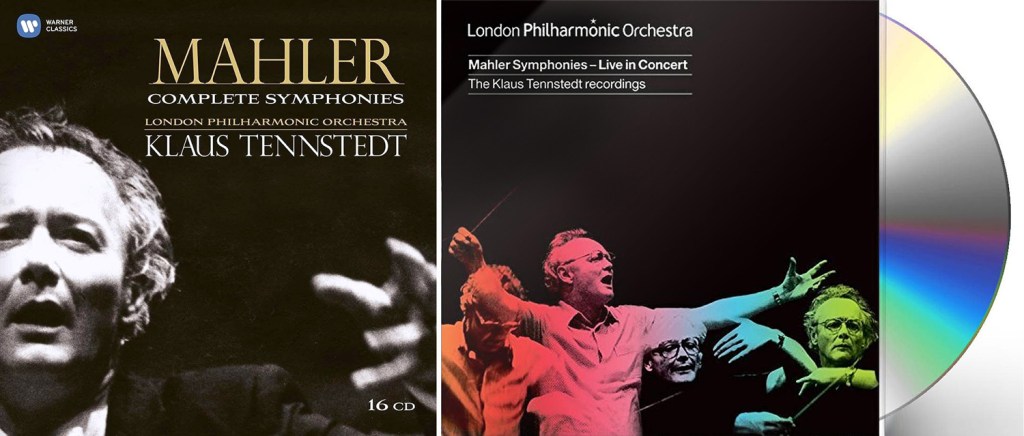

Michael Maltese (l.), Chuck Jones (r.) and their star (c.)

The seven-minute short was a series of attempts by a hungry coyote (originally named “Don Coyote” after Don Quixote) to capture and dine on a roadrunner (given spurious scientific names in the cartoons, such as “Disappearialis Quickius,” although in the natural world, Geococcyx Californianus). The Coyote comes up with an endless series of Rube Goldberg contraptions to catch the bird, who perpetually escapes usually leaving the coyote blown up by dynamite or falling to a sodden crash at the bottom of a canyon.

For 49 animated cartoons, the formula never really changed, each film just a catalog of gags with the same outcome. And after Warner Brothers closed down their animation studio in 1963, Jones took his Roadrunner into various newer permutations, both in theaters and on TV, never varying the formula, but later adding a sheepdog, or Bugs Bunny into the works — even a baby roadrunner and coyote.

The formula never changed, but the desert did. Several background designers worked on the films. The earlier ones, by Robert Gribbroek, were more realistic, but as time went on the landscape, designed by Maurice Noble, became both more abstract and more surreal.

Roadrunner landscape, early (l.) and late (r.)

But, to be honest, how can you really make such a landscape more abstract or more surreal than the actual thing. The Southwest, and particularly the Colorado Plateau of northern Arizona and southern and central Utah, is a wonderland of geoforms, with buttes rising up and canyons dropping down. And in the popular mind, they have become a generic version of the American West, the place setting for countless cavalry-and-Indians movies, and endless TV series.

The idea of a cartoonish Southwest landscape goes back before the Roadrunner. Beginning in 1913 and continuing until his death in 1944, cartoonist George Herriman filled Hearst newspapers with Krazy Kat comic strips, set in a bizarro world Coconino County, the original of which sits in northern Arizona.

Although now famous, the Krazy Kat cartoon strips were not terribly popular when they first ran. They were too weird for popular tastes. Only because the big boss, Hearst himself, loved them, they continued until Herriman’s death. But since then, Krazy has become a cult favorite.

Of course, just like the Roadrunner cartoons, they never changed. Gender-fluid Krazy is in love with Ignatz the mouse, who hurls bricks at the cat and is punished or admonished by Offissa Pup, the doggy policeman of Coconino County. A thousand changes are rung on the formula.

And behind them, the surreal landscape that was a stylized version of the Four Corners region, a landscape Herriman himself came to love through many visits to the Kayenta area just south of Monument Valley.

But, it should be noted that Herriman wasn’t the first cartoonist to fall in love with the Western landscape. It is often stated that the first cartoon strip ever created was The Yellow Kid, by Richard Outcault, which ran in the Pulitzer and later Hearst papers at the end of the 19th century. But the prize for being first has an equal claimant in Jimmy Swinnerton (1875-1974), who began producing the Little Bears strip for the San Francisco Examiner a few years earlier than The Yellow Kid.

Panel from Swinnerton comic strip, with Hopi kachinas

Like Herriman, the California-born Swinnerton loved the American West. When diagnosed with tuberculosis, he moved to Arizona. In 1922, he began a cartoon strip for Good Housekeeping magazine, titled Canyon Kiddies, about Navajo children and life in the Four Corners region. Each was a series of pictures with rhyming verse underneath.

In one, he almost predicts the Roadrunner cartoons, as a coyote eyes a rabbit (instead of a roadrunner) but asks, “It’s simply terrible to have a meal/ That can run much faster than yourself.”

Swinnerton was also a serious painter, and from the 1920s on, made many landscapes of the West. They were more realistic than his comic-strip landscapes, but were still a kind of stripped-down style that borrowed from the popular Art Deco esthetic of the times.

That style has proved durable over the decades. There are artists who prefer a more detailed, more photographic style, but many others seem to have realized that a smoothed-out, simplified version of the landscape was perhaps more expressive. They emphasized tones and colors above detail.

Maynard Dixon

Among the first serious artists who adopted the style was Maynard Dixon (1875-1946). Born in California, he later lived, and died, in Arizona.

Dixon began as an illustrator and painter of a kind of generic California Impressionism, but his career hit its stride with the landscape of the West, and a more Modernist approach.

What was a distinct style with Dixon later became a common vision for painters of the West. Simplified mesas and buttes, huge clouds above a low horizon, and dusty pastel colors.

Maynard Dixon

With Georgia O’Keeffe, geology turns almost to biology, as her many paintings of New Mexico seem almost like bulging muscles and twisting torsos.

Of all the artists working in this style, no one did more to make the style personal. You can spot an O’Keeffe from the other side of the room. Who knew that the most stubbornly cussed Modernist painter of the Southwest could share so much with Roadrunner cartoons?

What all these artists have in common is the reduction of sharp detail and an emphasis on color and general form. The desert Southwest surely demands such.

As the turn-of-the-20th-century art critic John C. Van Dyke wrote in his book, The Desert (1902): “Painters for years have been trying to put it upon canvas — this landscape of color, light, and air, with form almost obliterated, merely suggested, given only as a hint of the mysterious. Men like Corot and Monet have told us, again and again, that in painting, clearly delineated forms of mountains, valleys, trees, and rivers, kill the fine color-sentiment of the picture.”

Van Dyke continues: “The great struggle of the modern landscapist is to get on with the least possible form and to suggest everything by tones of color, shades of light, drifts of air. Why? Because these are the most sensuous qualities in nature and in art. The landscape that is the simplest in form and the finest in color is by all odds the most beautiful.”

Dixon (l.) and O’Keeffe (r.)

In my years as an art critic in Arizona, I knew many artists who found the color more important than the texture. The Art Deco style of Dixon or (more idiosyncratically) O’Keeffe proved to be infinitely malleable for their work.

Many more recent artists have adopted and adapted this style for their landscapes of the Southwest.

Dennis Ziemienski (l.), Martin Sabransky (c.), and David Jonason (r.)

There is a thriving market for Western paintings. (I had to deal with quite a bit of it during my stretch as art critic in Arizona, where a kitschy version, called “Cowboy Art,” was popular in toney art galleries. These artworks, filled with bronco busters and noble Indians, were often painted with considerable technical skill, but very little originality — they were really more merchandise than art).

But among the kitsch are quite a number of landscape artists, including Brett Allen Johnson …

G. Russell Case …

Gary Ernest Smith, who usually paints more Midwestern scenes, but occasionally gives a go at the Southwest …

And Doug West, whose work is often done in silkscreen, or mimics the silkscreen style, which is the simplified color-and-shape taken to extremes.

If you think we have wandered too far from the Roadrunner cartoons, they consider at least this one painting by Carol Bold:

Roadrunner cartoon (l.) and Carol Bold (r.)

But there are two artists I want to mention in particular, both of whom I knew back when I kept track of all the art being made in Arizona.

The first is Ed Mell, who began his career painting fancy cars as a commercial illustrator. Not finding personal satisfaction as a New York advertising artist, he took a job teaching on the Hopi Indian Reservation and rediscovered the landscape of the Colorado Plateau.

His early works tended to be influenced by Maynard Dixon, but as his career progressed, his painting tended to combine the Art Deco with a kind of Cubism, to what one might call “Cubist Deco.” More like the stylized landscape of the cartoons.

That Cubist Deco has made it to other artists, as well, including the above-mentioned David Jonason …

The other artist I want to bring up is Bill Schenck, who has also given us work in the Deco style …

But has also branched out into what can only be called a “paint-by-numbers” esthetic. It gives a hard edge to the otherwise more Impressionistic styles of his contemporaries.

The style has also been mixed with the techniques of Bob Ross, to make a kind of “furniture store” art. One example shows up as a background to MSNBC security analyst Frank Figliuzzi. It is a painting by gallery-owner and artist Diana Madaras.

And I couldn’t end this study without mentioning the Roadrunner esthetic of Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City.

He even has a few appearances of a roadrunner, just to let you know, wink-wink.

I collected more than 200 images for this essay, and I had to leave out so many that I wanted to include. But there is only so much space, and so much attention willing to be subjected to this rabbit hole.

But I did want to end with one final road runner, set in the landscape we’ve been discussing.

Click on any image to enlarge