In addition to this blog, which I have been writing since 2012, I have written a monthly essay for the Spirit of the Senses salon group in Phoenix, Ariz., since 2015. The readership for each site seems to have little overlap, and so, I thought if I might repost some of the Spirit essays on my own blog, it might achieve a wider readership. This one, originally from July 1, 2022, is now updated and slightly rewritten.

The world is fuzzy. I am constantly reminded of the fact that when looked at with any concentration, what might have seemed sharply focused, is, in fact, quite blurred.

No matter how precise we try to make our language, there is always a nimbus of ambiguity clouding our meaning. What we mean by a word, and what our hearer means is only explainable in a Venn diagram. Some overlap, much personal and distinct.

We keep trying to clarify our thought, to make it more precise, to nail down just exactly what we mean, but that whittled edge always seems to elude us and we are left with “sort of” and “it’s like …”

What I’ve come to understand is that it has to be that way, and that meaning and communication can only happen in that aura of mist and glimpse.

We try to sort out our reality with definitions and categories, but, so much is simply uncategorizable, and definitions are often murky.

I was re-reading my Lucretius, an epic poem about science written in Latin in the First Century B.C. De Rerum Naturae (“On the Nature of Things”) is some 7,000 verses long, divided into six books and explains the universe in surprisingly modern detail. Lucretius was an Epicurean, and spends a portion of his book explaining atomic theory. If you allow for the use of metaphorical thinking instead of mathematics, and allow for guesswork to replace the subsequent 2,000 years of scientific advance, the poem can often stun you with its prescience.

Yet, is De Rerum really science? Or is it poetry? Like a good epic poem, it begins with an invocation to a goddess. But like science, it spends its time discussing being and nothingness, matter and space, the atoms and their movement, the infinity of the universe, time and space. But then again, it’s in verse.

So, was Lucretius a poet? A scientist? A philosopher? I need an optometrist: It’s all gone fuzzy.

This uncertainty is constant in our intellectual lives. Is light a wave or a particle? Is Beethoven a Classical composer, like Mozart, or a Romantic, like Wagner? A case can be made either way. When did the Renaissance begin? Was Camus an Existentialist or an Absurdist? When and where, exactly did Latin turn into French, Spanish and Romanian? We tend to think of all these categories as discrete, yet, when looked at, they blur out. Can a Londoner really understand a Yorkshireman? They both speak what is called English, but evidence says Londoners are as confused by northern language as Americans are. We all need subtitles.

Language divides things up so we may talk about them. Cats are one one side, dogs on the other. Mammals on one side, reptiles, birds, and fish on the other. Animals are on one side, vegetables and minerals sit on the other side of the room. Divide, divide. Name, name.

But anyone who has ever tried to re-organize their homes or office has run into the problem: Here are letters; divide them into piles. Business letters, personal letters, old letters, current letters, personal letters discussing business, business letters with a personal P.S. added. Letters to you, letters to your wife, letters addressed to both. How many piles do you make? The biggest file by far can only be those uncertain of classification — and maybe next time you go through them, you can decide. In other words, the biggest pile is “miscellaneous.”

As the obscure philosopher Anne Burnette said, “The world has miscellaneous built into it.”

The same if you organize books. Fiction, non-fiction. But where on its best-seller list should The New York Times have put Edmund Morris’ Dutch, a semi-fictionalized biography of Ronald Reagan? Is poetry fiction or non-fiction? Is Lucretius science or literature? In the end, you wind up subdividing your categories so finely, that perhaps each volume gets its own subcategory. How is that different from chaos?

The New York Times now prints 11 weekly lists of best-sellers, all subdivided: Combined Print & E-Book Fiction; Combined Print & E-Book Nonfiction; Hardcover Fiction; Hardcover Nonfiction; Paperback Trade Fiction; Paperback Nonfiction; Advice, How-To & Miscellaneous; Children’s Middle-Grade Hardcover; Children’s Picture Books; Children’s Series, Young Adult Hardcover. And that’s not counting the monthly lists: Audio Fiction; Audio Nonfiction; Business Graphic Books; Mass Market; Middle Grade Paperback; and Young Adult Paperback.

Burnette says, organize your books by color. It’s as good as anything else. Even the Dewey Decimal System has “miscellaneous” built into it and the Library of Congress organization actually begins with it, called “General Works.”

Just talking with each other and trying to communicate requires fuzziness and imprecision. Trying to be too precise only invites misunderstanding. Total order and total chaos are, after all, identical.

I was once playing with my brother’s dog and thinking about scientific nomenclature. How should I classify Roxanne? She had a very distinct personality. A one-in-a-million springer spaniel, for sure. Science does it with a hierarchical layering of categories. Once we separate animals out from everything else, we then divide them up into phylum, class, order, family, genus, species. A dog, for instance is phylum chordate; class mammal; order, carnivore; family, canid; genus, Canis; species, familiaris. We usually only use the last two for identification: Canis familiaris.

But even the category “dog” can be subdivided into breed: schnauzer; doberman; chihuahua. Breeds get broken down, too: water spaniel; springer spaniel; cocker spaniel Indeed, the nomenclature is constantly being subdivided into sub-phylum, sub-order, etc. Taxonomists are fervid with smaller and smaller divisions. Family is subdivided into sub-family, tribe and sub-tribe; there are subgenera and subspecies.

But these categories are sometimes squishy. Not every taxonomist agrees, and the labels can change over time. And so they can’t be satisfied with one rank, but often try to find distinctions within genera so they may create new ones. In times past, for instance, a lion was classified as “Felis leo,” that is a cat of the lion species; But no, that wasn’t enough. It was noticed that cats come in two varieties: Small and large — i.e., those that can purr and those that can’t. And so, Felis was divided into Felis and Panthera and lions became Panthera leo.

But even that wasn’t enough for some taxonomists, who found enough difference between tigers, leopards, on one hand — and lions on the other, to create yet a new genus: Leo, held solely for our leonine brethren, and so, it became Leo leo. But there were African lions — Leo leo leo — and the subspecies of Asiatic lions — Leo leo persica. Enough already. Indeed some taxonomists have gone back to using Panthera. And the Indian lions have been relumped back into Panthera leo. Not all zoologists agree, and if you visit different zoos, you will find different labels attached to cages, depending on who is choosing the name (and also how often zoo officials update their signage).

To take the whole enterprise to absurdity, that dog we were discussing can be so roundly classified as to prove the meaninglessness of the attempt to do so. We classify in an attempt to make order of chaos. But the more we subdivide, the more chaotic we make things. Your dog is not only separated out as a chordate mammal carnivore canid of the familiaris species, but also of the breed spaniel, the kind springer spaniel (they come in multiple colors), and the individual name, Roxanne. Every dog can be thus subdivided down to its individual name, meaning that at the end of the most precise descriptions, there are as many categories as there are things in the cosmos — in other words, chaos.

In other words, the more precise a word is, the less it describes, and perfectly precise language is functionally meaningless. Meaning depends on fuzziness. “Dog” is ambiguous, but we all know what is meant, more or less. “Roxanne” has only meaning to those who know that particular dog.

And so, fuzzy is good. Precision is a phantom. Fuzziness helps us communicate, creates a wider field of shared experience.

But I’m using language only as an exemplum. Fuzziness is characteristic of the world in general, and is a necessary, or at least helpful ally in negotiating it.

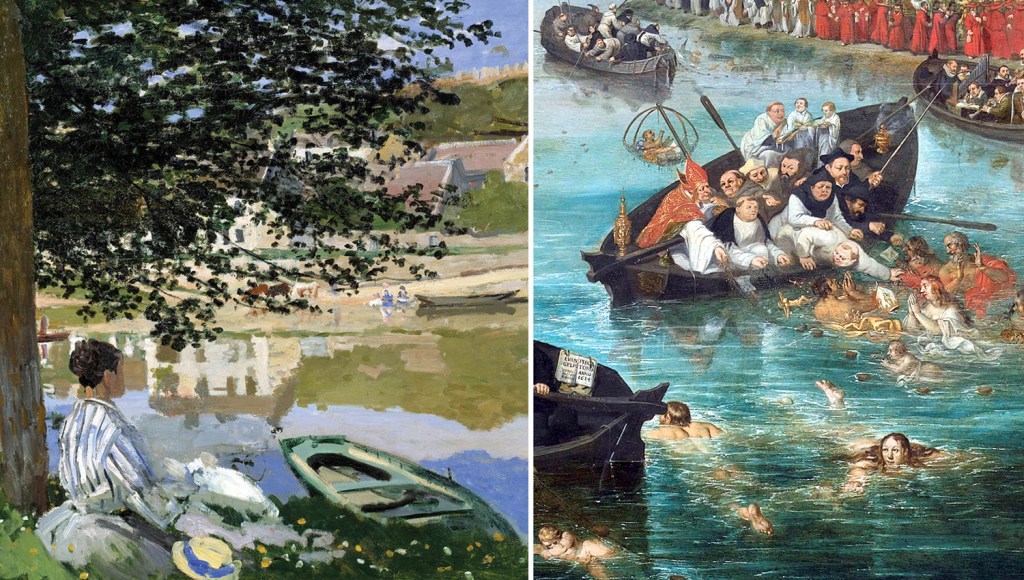

Like an Impressionist painting, which can actually look more real than the finely detailed and finicky painting of the Renaissance and Baroque. The fuzzier river reflections in the Impressionist painting are almost photographic compared with the sharply detailed but unrealistic reflections in the older painting.

(And where exactly does the Baroque shade into the Rococo? Or the Romantic Age become the Victorian? Where did Modernity begin? With Picasso or Einstein? With the Crimean War? With Napoleon? With the Enlightenment? With the Renaissance? With Rome? With Egypt? With agriculture? History is always fuzzier than our outlining of it.)

Where do you, as a person, begin and end? It would seem that one’s skin is the border between self and not-self. But proprioception can create a different self: Amputees can “feel” their selves extend into phantom limbs. And for most, if you are driving a car, say, your sense of selfness can extend to the limits of the car — you become one thing operating on the streets, like man and horse becoming centaur. You can back into a parking space because you have a proprioceptive sense of how far you and your automobile extend into space.

And you can feel uncomfortable if someone invades your personal space. So, where does the self end?

National borders and identities have the same issues. When Winston Churchill wrote his books, he titled them History of the English Speaking Peoples, because he couldn’t draw a line around England without extending it to Scotland and Wales, and then the United States and Canada, and then, what about Australia and New Zealand?

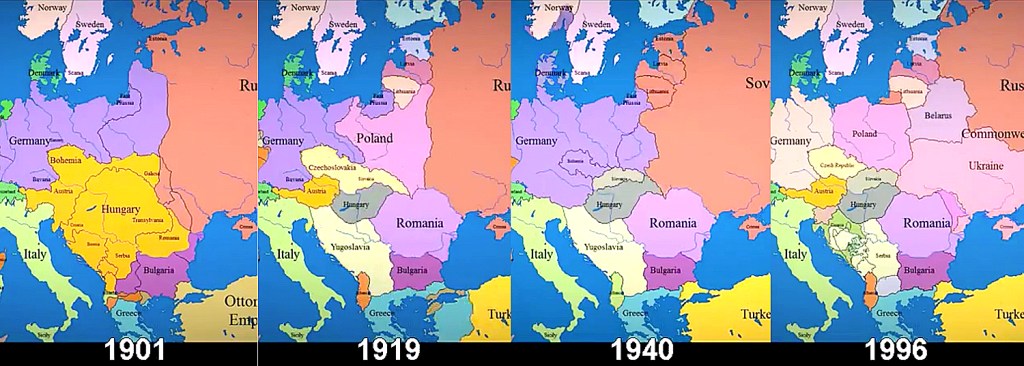

National borders keep shifting. Poland has appeared and disappeared many times over history. In the 20th Century alone, it disappeared and reappeared twice, and after World War II, the entire country picked up its skirts and skidded west by roughly 200 miles, ceding part of its former self to the U.S.S.R. and taking in turn a chunk of what was used to be eastern Germany.

We are watching borders shift constantly. Where will Ukraine be two years from now? South Sudan popped into existence; Yugoslavia evaporated.

We think of the world in nouns, as if it were static, but truly it is all verb, and the constant motion blurs every outline.