French composer Camille Saint-Saens was smarting from a concert tour in Germany that didn’t go over well, and so, in 1886, he withdrew to small Austrian village and wrote a short piece about music critics, which he called Personnages à longue oreilles, or “Characters with long ears,” in which the critics bray in imitation of asses — “hee-haw.” It is barely 45 seconds long, but it seems to have given him a bigger idea.

And so, he wrote thirteen accompanying short, mostly comic, compositions, each describing another animal, and had them played privately as La Carnaval des Animaux, or “The Carnival of Animals.” He wrote his publisher in Paris that he knew he should be working seriously on his Third Symphony, but that instead, he was having “such fun.”

Yet, fun wasn’t what he wanted to be remembered for. He was to be a serious and honored composer of five symphonies, many concertos and 12 operas. And so, he refused to allow the Carnival of Animals to be published until after his death.

The irony is that, along with his Danse Macabre and the Bacchanale from his opera Samson et Dalila, what he is best remembered for, and most loved, is this 25-minute-long musical menagerie. In fact, his best-known piece is undoubtedly The Swan, for cello and piano, the second-to-last section of the Carnival.

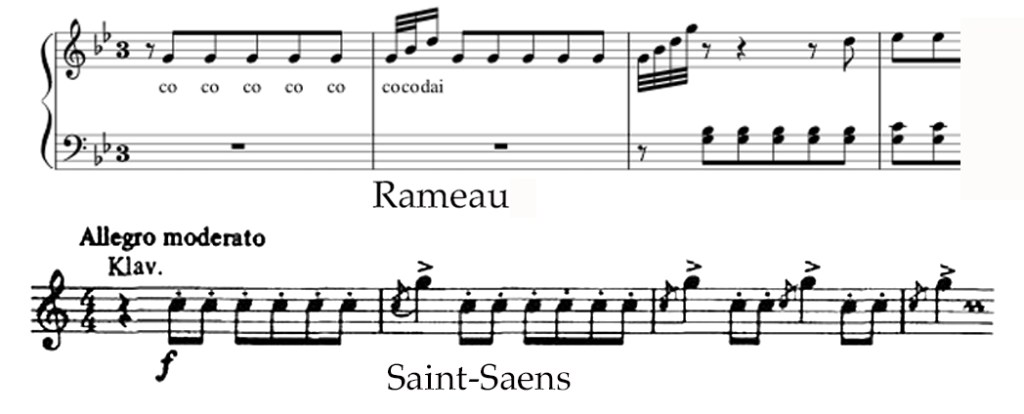

Many of the pieces parody famous music by other composers and popular songs, but I want to pick out, in particular, the second section, Poules et Coqs (“Hens and Roosters”), which gets its main theme from a 1726 piece for harpsichord by Jean-Philippe Rameau, called La Poule (“the Hen”), from his Suite in G from his Nouvelles Suites de Pièces de Clavecin.

You can see the similarity, even in these few bars.

But that set me off on a search for other music about or imitating animals. It’s not just “Old MacDonald” and his “oink, oink, here and an oink, oink there,” but in fact, a long history of musical animals. Some famous, some obscure.

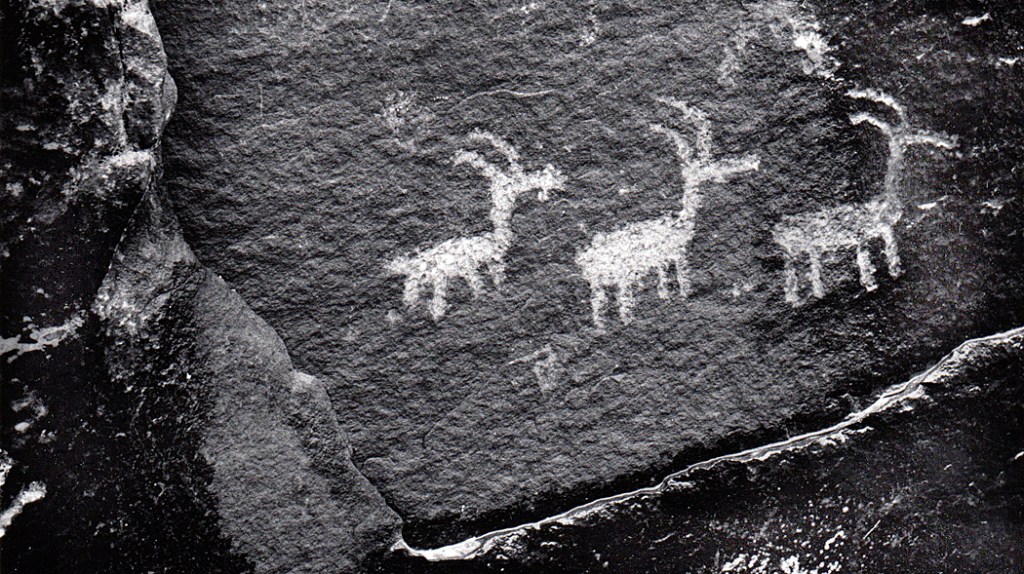

Of course, such animal imitations go back to prehistory, if we believe the musicologists, who tell us that they often feature in folk songs, from all around the world. “Old MacDonald” is only one of them in English. But there are Chinese songs, Turkish songs, Swahili songs, all with animal noises as part of their lyrics.

But I was most interested in Western art music, after the invention of musical notation and printing, where the music could be tracked down and maybe even listened to (on YouTube when available).

The earliest I found was from the middle of the 13th century, a ditty called Sumer is icumin in, with its lyrics “lhude sing cucu,” which have been set to various tunes, most of those I have heard include a melodic line that imitates the falling third of the cuckoo birdcall.

No doubt because the cuckoo’s call is so distinct and so clearly a falling third, it is about the most frequently used birdsong in classical music, as we will see (followed by the trilling of the nightingale).

Indeed, the next entry is Par Maintes Foy, by 14th century composer Jean Vaillant, which not only has the singers call out the cuckoo and the nightingale, but also the goldfinch, starling and quail. “Lire, lire, lirelon,” Toowee, toowee, toowee.”

But it isn’t all birds. In 1505, Josquin de Prez, perhaps the most famous of all early composers, published his El Grillo, which has its singers imitate the sound of a cricket.

Clement Jannequin (11485-1558) wrote Le Chant des Oiseaux (“Song of the Birds”) with a blackbird singing “Ti-ti, pi-ti;” the nightingale trilling on “Frian, frian;” and the cuckoo again doing his “Cu cu, cu cu.”

Pierre Passereau (1503-1553) wrote Il est Belle et Bon, in which a wife praises her husband for being so compliant and even feeding the chickens, which she then imitates “co co co co da.”

In his Book of Ayres with a Triplicitie of Musicke, from 1606, John Bartlett published a madrigal called Of All the Birds That I Do Know, in which words get repeated in a way that clearly evokes the chatter of birds. “Of all the birds that I do know, Philip my sparrow hath no peer … Philip will cry still, ‘yet, yet, yet, yet, yet, yet.’”

As we leave the vocal Renaissance and enter the more instrumental Baroque age, we begin having fiddles and hautboys imitating various birds and beasts.

Sonata Representativa (1669) by Heinrich Biber dedicates a movement each to imitations of nightingales, cuckoos, frogs, hens and roosters, quails and cats. Written for violin and continuo, it alternates short interludes with sections depicting animal sounds. After a Preludio, a Nightingale on the violin sings four eighth notes repeated and a long trill over a pedal; a Cuckoo hits repeated fast eighth notes making the usual cuckoo sound; then come Frogs with an appoggiatura of dissonant seconds, sounded together, and resolved upward, over and over to make croak; Hens cluck with upward portamento; quail have a repeated dotted rhythm “dah, da-dah;” a Cat comes mewing portamenti in nursery-rhyme-like tune; then all is rounded off with a march.

Georg Phillip Telemann wrote his Alster Overture, with a fourth movement imitating “Concertizing Frogs and Crows.” There is also a swan in another movement.

Of course, the most famous and familiar sounds come from Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. In the opening movement of the four concertos, we hear the squawking of birds. In the second movement, he has dogs barking, and in Summer, the slow movement has the strings buzzing around as a swarm of flies.

But it wasn’t only the Seasons: In his Flute Concerto, op. 10, no. 3, “Il Gardellino,” he has the flute imitate a goldfinch.

The keyboard is well represented, too. In addition to Rameau’s La Poule, there is Louis-Claude Daquin’s The Cuckoo and Francois Couperin’s Le Moucheron (“The Gnats”), to say nothing of Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonata No. 30 in E-flat, known as the “Cat Fugue,” with a tune that imitates a cat walking distractedly up a harpsichord keyboard (an early version, I guess, of Zez Confrey’s Kitten on the Keys).

Then, there’s Georg Friedrich Händel’s Organ Concerto No. 13, known as “The Cuckoo and the Nightingale,” from 1739, with birdsong in the second movement.

There’s no counting the birds, beasts and bugs in the music of Franz Joseph Haydn. He loved a good joke, and among his 104 symphonies and 68 string quartets (to say nothing of his 41 piano trios, 52 piano sonatas, and 126 baryton trios — not counting the additional 36 baryton works for that obsolete instrument with other pairings) you can find Symphony No. 82, “The Bear;” Symphony No. 83, “The Hen;” String Quartet op. 33, no. 3, “The Bird;” Quartet op. 50, no. 6, “The Frog;” Quartet op. 64, no. 5, “The Lark.”

And in his magnum opus, The Creation, in Part 2, describing Days 5 and 6 of the biblical creation, he has the orchestra imitate multiple birds and animals, including an eagle, a whale, a stag, lowing cattle, and even a worm.

As we move into the Romantic 19th century, the animals are truly fruitful and multiply, beginning with the slow movement of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, which ends with a cadenza that quote quail, nightingale and cuckoo.

So, let’s make a quick list — as quick as it can be with such a long zoo parade. There is Schubert’s song, The Trout; Robert Schumann’s Papillon and the Prophet Bird; the braying donkey in Mendelssohn’s Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream; Chopin’s Etude, op. 25, no. 9, known as “The Butterfly Etude.” Not forgetting that it was said that Chopin’s “Minute Waltz” was inspired by the composer watching his dog, named Marquis, chasing its tail.

Cats screech over and over in the Cat Duet, attributed to Gioacchino Rossini (jury’s out on the authorship).

To continue: There are birdsongs in the woodwinds in Bedrich Smetana’s Bohemian Woods and Fields; The Flight of the Bumble Bee, from the opera Tsar Saltan by Rimsky-Korsakov; The Lark by Mikhail Glinka; the Ballad of the Unhatched Chicks from Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition; the “Dying Swan” and the “Dance of the Cygnets” from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake; and The Swans of Tuonela by Jean Sibelius.

In Scandanavia also, we have, but Edvard Grieg: The Butterly; Little Bird; The Pig; The Horsefly and the Fly; and Cow Call. And from his contemporary Norwegian composer The Hare and the Fox by Harald Saeverud.

Serge Rachmaninoff’s Etude Tableau, op. 39, no. 2 for piano is called “The Sea and the Gulls.” Enrique Granados wrote The Maiden and the Nightingale. And Richard Strauss caused some grumpiness and consternation in his staid German audience when, in the middle of his tone poem Don Quixote, he has the orchestra imitate a herd of sheep. But Strauss was no stranger to vulgarity: It is one of his strong points.

Which brings us up to date with Saint-Saens’ Carnival of the Animals, which gives us, in order: a lion; hens and roosters; wild asses; tortoises, the elephant, kangaroos, fish in an aquarium, personnages a longue oreilles; a cuckoo in the woods; birds in the air (aviary); pianists practicing scales; fossils; the swan; and a finale that brings back many of the menagerie.

But it’s not over yet. As we move into the 20th century (and the winding-up of the 19th), there are some very beautiful evocations of nature and the animals in it. Such as: Delius’s On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring. Or the fourth movement of his North Country Sketches, called “The March of Spring: Woodlands, Meadows and Silent Moors.”

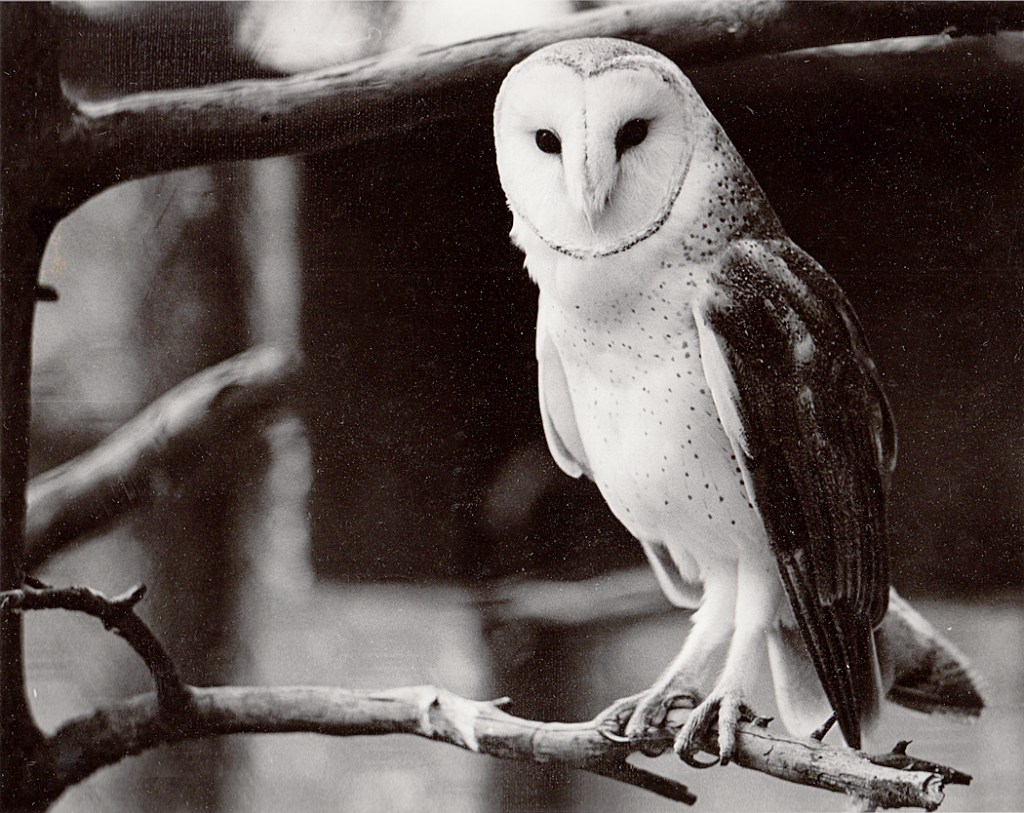

Ralph Vaughn Williams gave us one of the most beautiful violin show-off pieces in his The Lark Ascending. He also put some swarm sounds in the overture to his ballet The Wasps. Edward Elgar wrote for voices a very peculiar piece called Owls: An Epitaph. Pianist Leopold Godowsky gave us, in his Java Suite, a movement called “Chattering Monkeys.”

Claude Debussy wrote Poissons d’Or (“Goldfish”) in his Images, Book 2, no. 3; and his counter-Impressionist Maurice Ravel wrote Oiseaux Triste (“Sad Birds”) in his Miroirs. Paraguayan guitar virtuoso Agustin Barrios wrote Las Abejas (“The Bees”).

Ottorino Respighi took music from early composers and reworked and orchestrated it in his Gli Ucelli (“the Birds”), with movements called “The Dove,” “The Hen,” “The Nightingale,” and “The Cuckoo.” But he goes one better in his Pines of Rome, by including an actual sound recording of a real nightingale. (Tape recorded animal sounds return later in the century.)

Whole chapters might be given over to Gustav Mahler, who began his very first symphony with cuckoo calls, and inserted all sorts of animals, birds, and natural sounds into his music, including cow bells in his Sixth Symphony and a donkey braying in his Third, so say nothing of the sleigh bells in the Fourth, fish in his song Saint Anthony of Padua Preaches to the Fishes. They show up again in his Second Symphony. Nature is never far from the surface in Mahler’s music.

But more than in Mahler, bird song is everywhere in the music of Olivier Messiaen. The man was obsessed with bird sounds. He used them often as the source of his thematic material (I hesitate to call them tunes), not simply transcribed, but often lowered in pitch, slowed down radically, or even played upside down or backwards.

His 1958 Catalogue d’Oiseaux (“Catalog of Birds”) is a collection of 13 pieces for piano, each of which is based on the call of a different bird, running from the Alpine chough, the Eurasian golden oriole, the blue rock thrush and the tawny owl, through the woodlark, Cetti’s warbler, the common buzzard and the Eurasian curlew. The whole catalog takes just short of three hours to perform.

Then, there is the Petites Esquisses d’Oiseaux (“Small Sketches of Birds”) from 1985, six short piano pieces, about 2 minutes each, that picture blackbird, skylark, thrush and robin. The L’Abîme d’Oiseaux (“Abyss of Birds”) is one movement from the Quartet for the End of Time. Le Merele Noire (“Blackbird”) is from Le Reveil des Oiseaux (“Dawn Chorus”), La Fauvette des Jardins (“Garden Warbler”) — on and on through his works, the birds are the foundation of his music. A devout Catholic, Messiaen saw birds and their song as emblematic of the beauty of God’s creation.

Although, to be honest, it is usually hard to hear the music as bird calls, since they are so transformed by the composer. You kind of have to take his word for it.

It’s hard to keep up with Bela Bartok, also. He wrote many short piano pieces, some of which bear the names of animals. But there’s The Diary of a Fly (Mikrokosmos vol. 6, no. 42), and the famous Bear Dance from his Ten Easy Pieces.

But he is best known for the several “Night Music” pieces, from his Out of Doors suite for piano; the slow movement of his Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta; and the middle of his Piano Concerto No. 3. Wikipedia lists some 20 compositions where Bartok employs his Night Music, which imitates the sounds of a Hungarian summer evening, with insects chirping, birds singing and frogs croaking. The effect can be miraculous.

(Duke Ellington wrote his own versions of night music in his Queen’s Suite, with movements called “Sunset and the Mockingbird,” “Lightning Bugs and Frogs,” and “Apes and Peacocks.” I mention it here because, really, Ellington is classical music.)

Igor Stravinsky has elephants dancing in his Circus Polka, and nightingales warbling in his Chant du Rossignol. It has been reported that his Rite of Spring contains quotations from Russian folk songs about animals. I’m taking the musicologists’ word for that.

Sergei Prokofiev has his own menagerie in Peter and the Wolf, and Malcolm Arnold attempted to add animals to Saint-Saens’ zoo with his own Carnival of the Animals, written for the comic Hoffnung Festival in 1960. His additions are: The Giraffe; Sheep; Cows; Mice; Jumbo; and Chiroptera (Bats) — the last of which is a joke, since the musicians “play” so high in frequency that “only bats can hear it.” The audience hears silence until a final tinkling on a bell.

Several 20th century animal-musics were created as humor or jokes, including The Monk and His Cat from Hermit Songs, op. 29, no. 8, by Samuel Barber; The Cat and the Mouse by Aaron Copland; the Promenade (Walking the Dog), written by George Gershwin for the Fred Astaire film, Shall We Dance, and The Procession of the Cats on Solstice Night by Bohuslav Martinu.

Then, there’s Ferde Grofe’s On the Trail from the Grand Canyon Suite, with its clopping hooves and braying donkey.

The Critics

Francis Poulenc took on the grasshopper, bear, lion and roosters for his Les Animaux Modèles, a ballet from 1942 based on the fables of La Fontaine.

I mentioned earlier Respighi’s recorded nightingales in The Pines of Rome. Alan Hovaness famously used recordings of the humpback and bowhead whales in his And God Created Great Whales. (George Crumb’s Vox Balaenae does not include actual whale songs, but uses electric flute, electric cello and amplified piano to imitate both whale songs and seagulls.)

And in 1972, Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara wrote his Cantus Arcticus, subtitled Concerto for Birds and Orchestra, which uses recorded sounds of birds from northern Finland against a symphony orchestra.

This list does not exhaust the trove of animal-inspired concert music, but it is what I could dig up without spending two years on a doctoral dissertation. It is a tradition that continues, both in a simple vein, as with Sally Beamish’s Songs from Hafez, which reference the nightingale, the peacock and the hoopoe, and the more avant-garde work, such as Chris Hughes’ piece for cello and bird recording, Slow Motion Blackbird, which repeats the blackbird call for six minutes, slowing down each bar of music 5 percent (without changing pitch) until it is a slow, almost unfollowable adagio.

Most of this music is easily available, either on commercial recordings or through a YouTube video. Chirp chirp.

Ouroboros: Infinity