The best Christmas I ever had was the Christmas of four gifts.

It happened on the Hopi Reservation a few years ago, when my wife and I left Phoenix because we just couldn’t take another holiday season under the palm trees.

Like many who lived in the desert, Carole and I grew up elsewhere, where Christmas meant freezing weather and the possibility of snow. Santa rides a sleigh, after all. But in Phoenix, Santa wears sunglasses. It just doesn’t seem right.

Not that we thought we’d find a traditional Christmas among the Hopi. Their traditions are rather different. But we thought we could at least escape the TV beer ads littered with reindeer and find something new outside the city where the backyard Christmas barbecue passes for holiday cheer.

Maybe we couldn’t have our old traditions, but we could start new ones.

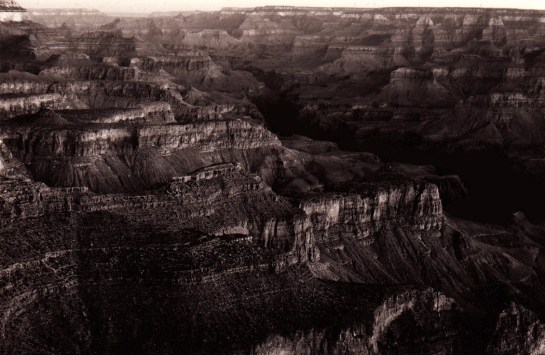

If the traffic and commotion of the city get on your nerves, no better tonic exists than a visit to the three great mesas of yellow-gray sandstone that rise like gigantic library lions from the vast plains of the Colorado Plateau. Atop them the Hopi have built most of their villages, all from the stone of the hills.

From the mesa-top the view is biblical: You can see for what seems forever. The San Francisco Peaks sit on the horizon, some 75 miles to the southwest, yet they seem so close you feel you can walk to them.

On that Christmas Day, the temperature was about 29 degrees and the sun was low and cold, poking through an intermittent overcast. We stopped at the base of First Mesa to get gas at the little store in Polacca. We also bought a few gifts — some coffee and sugar — to bring to the women on the mesa-top who give tours of the village.

When we got back in the car, we discovered the woman behind the counter had quietly dropped candy and fruit into the poke with our purchases.

That was the first gift.

WALKING INTO HISTORY

The highlight of a visit to the three villages atop First Mesa is a tour of Walpi. The Hopi have lived in the community on the prow of the mesa for at least 1,000 years and some of the stone homes seem to be almost that old.

You park your car in the middle village, Sichomovi, and find a tour guide in Ponsi Hall, the community center. From there, you walk out across the narrow stone causeway to Walpi. Our guide was a woman we had met on several previous visits to the area. She is a warm, generous woman who was free with her answers to our many questions. I will not embarrass her by printing her name.

She showed us the ancient masonry, the village layout, the meaning of the kivas and their spindly ladders that protrude from the ground. She told us of the kachinas, of blue cornmeal and of pahoes , or prayer sticks, whose feathers danced in the breeze on the edge of the mesa.

She also told us of her life in San Diego and how after years away from the mesa, she felt drawn back to it.

And she told us how, like many Hopi women of First Mesa, she makes pottery.

Unlike most, though, she doesn’t make bowls, but effigies of turtles.

”They are like the Hopi,” she said. ”They live a slow-paced life.”

At the highest point of Walpi we came to the home of her aunt, who is one of the better-known Hopi potters. The old woman and Carole hit it off perfectly. They seemed to speak the same language.

They talked for quite a while. At one point, Carole asked if she knew where we might buy some of the blue cornmeal we had seen all over the reservation, and the woman reached a brown paper bag down from a high shelf and gave it to Carole, with instructions for cooking Hu zru’ su ki , or fried blue-corn polenta.

And when we bought one of her bowls, she smiled and whispered something in Carole’s ear and sprinkled some corn pollen into the pot.

That was the second gift.

OFF THE USUAL TOUR

Then, on our swing around the north side of the mesa top, our guide stopped in front of one small, square building and invited us in. It was her home, and inside, her daughter was putting the final touches of frosting on a batch of Christmas cookies.

The small room, with its stone floor covered with small rugs, was a toasty 75 degrees, with a fire going in the woodstove and condensation beading on the icy window glass. The family was bustling around, with Uncle in the back room attaching some down to the end of a ”lightning stick” and two boys helping the daughter with the cookies the way youngsters always help — by eating them.

A narrow shelf ran around the top of the room, about a foot below the ceiling, holding a collection of kachina dolls, lightning sticks, a toy bow and arrow and pottery.

Our guide explained what they were and handed out cookies. They were angels, and they were the best Christmas cookies I’ve ever eaten.

That was the third gift.

So, it was Christmas Day in the gracious, generous Hopi home, spending the afternoon with the family of a woman we now consider a friend.

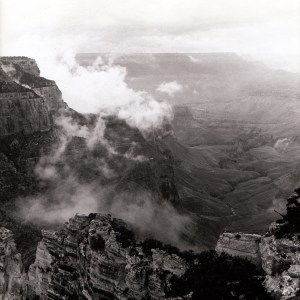

When we stepped back out into the cold to leave, snow was falling all over Hopiland.

And that was the fourth gift: the wonderful warmth of Christmas snow, dropping gently in large flakes, catching on our hair and coats.

So, I say on leaving the mesas in my best attempt at Hopi: Quo-Quai – Thank you.