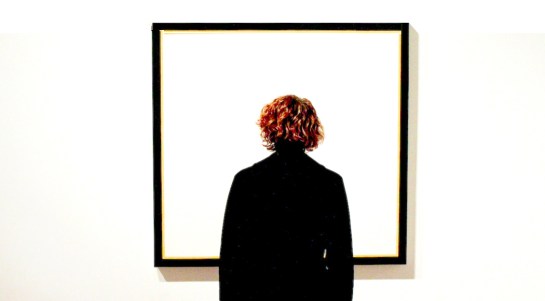

Artist Robert Ryman (1930-2019) made a career with his white paintings. Over and over, he applied white paint to canvas, paper, or board, always with some degree of change in application or tint or texture or shape.

Two years before his death, he donated 21 of his pieces to the Dia Art Foundation in New York. Before its closing in 2014, the Hallen für Neue Kunst in Schaffhausen, Switzerland, had a collection of 29 Ryman white paintings. So, there have been a lot of them.

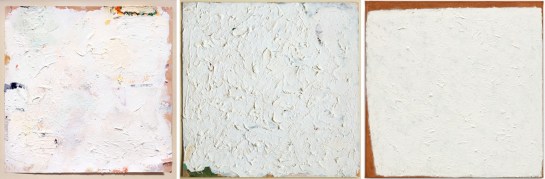

Three Rymans, L-R: from 1959; 1962; 2012

His work has been accepted into many museum collections, but there has been a backlash.

“Aspects of Ryman’s work definitely stink of seeing what he could get away with,” wrote one critic. Another said, “Ryman is the undisputed master of showing precisely which part of the wall you are supposed to stare at.”

Robert Ryman

There seems to be a widely held belief in the general public that a good portion of art being made these days is a sneaky attempt by artists to put something over on them. That art — at least that art being sold for millions at auction — is a scam. And that artists are hucksters laughing at us all meanwhile getting rich as Scrooge McDuck through our collective gullibility.

“A literal blank canvas? That could symbolize the artist’s emptiness.” And, of course, “If my 5-year-old could do that with his eyes closed, it’s not worth a fortune.”

I am not going to try to defend the rarified world of the art market, nor of any particular trendy piece of celebrity art. One should never, ever confuse the art market with the art. The art market is not a function of the the art world, but of the financial world, where people with too much money buy and trade what is currently valued by the market, as investment or even to launder questionable dollars. Very few artists have anything to do with this crawling underbelly of financial worminess. And even less is fluctuating market value a measure of esthetic worth.

The art and the market are parallel universes, and let’s face it, the overwhelming majority of working artists don’t become rich, and in fact, often have to work other jobs to pay for their need to make art, since their artwork cannot support them. A few solid and successful working artists make a living, but seldom making over a decent middle-class income. In other words, they are working stiffs.

When they were young, probably at a university art program, they get caught up in various trendy ideas about art and get lost diving down this or that rabbit hole, thinking all the while that they are in the process of transforming the history of art. If they have any real talent, they outgrow these fantasies when out in the world attempting to make a living as commercial artists, product designers, advertising artists, or even fine artists, struggling to make ends meet. They are an indulgence of youth.

But is will say that, as a working art critic for most of my adult life, who has known many artists and been friends with them, I have never ever come across one who thought he or she was pulling the wool over the public’s eyes. To a person, they were sincere, sometimes heartbreakingly so.

I don’t mean to defend a lot of the goofy art that ventures out into the world. A lot of it is bad or at least mediocre. And a great deal of it is derivative: imitations of what earlier artists have done.

Artists can develop cockamamie ideas, have brainstorms of breathtaking stupidity, or at least monumental unoriginality or brilliant vapidity. But they are not trying to scam the public. They actually take these things seriously.

I remember seeing a production where a local Arizona artist wore a coat made from pork chops. (And she assured us the meat was past its sell-by date, and would have been thrown out, so she was not wasting food).

Another hung a 3-foot cube of ice from the ceiling by a wire and watched for two days as the weight of the melting ice pulled it through the cutting wire till it dropped to the floor.

And if I never see another painting of nude lesbian vampires flying out of erupting volcanoes, it will be too soon. Who knew that was a trope?

Every one of these artists was dead serious about their ideas. (And not one got rich from the work.) But please remember that over the whole course of human existence, most things that were done were either made badly or aspired to a level of mediocrity. The work in the art history books is skimmed from the top surface of what boils up from the bottom.

Getting back to Ryman, he was not the first to make a white painting. In 1918, Russian Suprematist Kazimir Malevitch made White on White, with a tilted white square on a larger, whiter square. (A few years earlier, he had made a completely black painting, called Black.)

L-R: Malevich; Rauschenberg; Manzoni

In 1951, Robert Rauschenberg made a series of white paintings, using a paint roller to apply flat white wall paint to panels of canvas and joining several panels together to form larger works. For Rauschenberg, the idea was that the blank canvases would change appearance depending on the light hitting them, the shadows in the room, the number of people in front of them, and so they were meant to be visually active — at least to those who were willing to pay attention to them and the take them seriously.

Another avant-garde artist, Piero Manzoni, offered up a canvas plastered over in kaolin clay — the white clay of porcelain — in another series of “Achrome” or “colorless” works of art, made from white wool, rabbit skin or phosphorescent paint.

(Manzoni is probably most famous for allegedly canning his own feces (Merda d’artista, it said on the cans). In 2015, one can sold at Christie’s for the equivalent of about $240,000. As for artists getting rich off fraudulent art, Manzoni originally sold the cans for $37 each. It was the auction house that got rich, along with the owner who offered it up. All of which rather made the artist’s original point: He made the shitcans as an intended critique of consumerism and the waste it creates).

And in many cases I have come across, the artist’s idea is genuinely worth exploring, even if the non-artist public may scratch their heads. Artists see the world differently from civilians. They worry about things that never occur to normal people.

Like: If a piece of white paper sits with a shadow over a corner of it, is the whole page white? What is white? What do we mean by white?

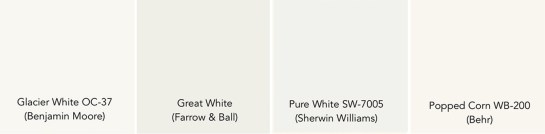

How may whites are there? Paint companies offer dozens of paint cans, each labeled in some form as white, and each different. Whites come in cool and warm varieties, as ivory, as snow, as off-white.

White is not a single thing. If we take a piece of white paper and shine a high-power halogen lamp at it, it gets whiter. So, would a stronger light make it even whiter than that? Like temperature, whiteness is more a judgment than an actual quality.

And so, Ryman seems to have wanted to investigate how white survives in various textures, matte or glossy surface, in contrast with other whites, compared with neighboring colors. All those different white paintings were not just repeats of the same blank canvas.

It may not be that Ryman’s art is world shaking. I’m not sure he himself thought of them as the last word in the evolution of art history. But he was quite serious about seeing what he could find out about the universe of white.

Adrian Searle of The Guardian newspaper explained in his obituary of the artist, “Ryman worked with white, and the different kinds of whiteness different paints and pigments produced throughout his career. Lead, zinc, barium and titanium, chalky whites and hard industrial whites, silky whites and bone whites, kitchen whites and shroud whites, numinous whites and dead whites. Whites that seem to spread outward and emit light as we look and whites to fall into. The variety of their opacity, depth, brilliance and dullness all interested him. We apprehend them all differently, and differently again depending on the materials they are painted over and how they are applied, what their binders are and how much they are diluted all make a difference.”

Art, of course, isn’t a single thing. If you think painting is about making pictures of things, then white paintings don’t count. If you think they about expressing emotion, you may look in vain to find much of it in bland white; if you think art is primarily about beauty, you must acknowledge it in the eye of the beholder — remember that scene in the film American Beauty, when Ricky Fitts plays his camcorder video of a plastic bag blown about in the wind and says it is “the most beautiful thing” he has ever seen. When our attention is focused on the bag, we can suddenly see its beauty. It is the direction of focus that awakens our awareness.

Many artists attempt to show us what we habitually ignore, to make us pay attention. Awareness — the sense of seeing the importance of the things of this world — is one of the goals of a certain branch of art. And attention must be paid, even to white.

One of the most famous examples, that has been a whipping boy for the crowd that thinks art is frivolous, is the piece of music titled 4’33” by John Cage. For its performance, a pianist sits at his piano for the four-and-a-half minutes of the piece and does nothing. The aural equivalent of a blank canvas.

For those without ears to hear, it is a lousy joke, or a scam pulled by the composer. But Cage’s point was that what filled the concert hall was never silence, but a cacophony of random sounds — programs rustling; people coughing; the air conditioning cycling; perhaps a police siren on the streets outside the hall; and even the sound of the blood pumping through the audiences’ ears. There was something to be paid attention to.

I had scoffed at the idea of this music for years, until I heard it performed live and its meaning hit me like a ton of bricks.

Admittedly, it is not a revelation that one can repeat. Once you get the message, you have it and don’t need to be jerked awake a second or third time — which makes the many imitations of Cage’s piece, such as the Two Minutes Silence track on the John Lennon-Yoko Ono album, Unfinished Music No. 2: Life With the Lions rather a pretentious knock-off rather than a meaningful experiment.

It is easy to misunderstand art when it doesn’t play by the normal rules, or tries to get the viewing or listening public to experience the world in a new way, or understand an otherwise wordless idea.

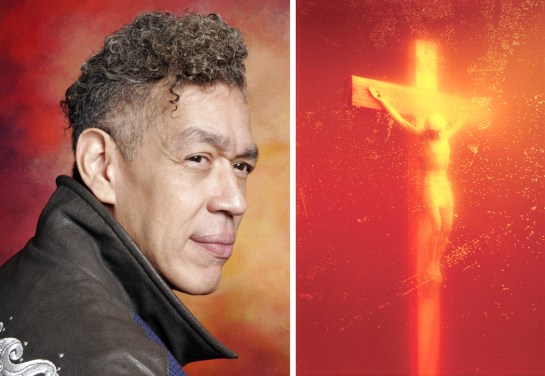

Perhaps the most famous (somewhat) recent example of this was the anger and outrage expressed in the late 1980s when Congressional Republicans attempted to defund the National Endowment for the Arts over the photograph called Piss Christ by Andres Serrano. The artist received death threats, the work was frequently vandalized when exhibited.

It was described as a photograph of a crucifix in a jar of urine, but there was no jar to be seen: All it was was a crucifix in a glowing golden light and a few bubbles. It was quite beautiful, if you could forget the title.

But what few of its critics recognized was that Serrano was a pious, believing Roman Catholic Christian who was looking at his faith in a way perhaps only an artist would, to emphasize the corporality of the incarnation: God becoming flesh.

I say, “only an artist would,” but I could also say, “an artist or a child,” for I remember when I was a boy, various Catholic friends of mine, in the sixth grade, wondered whether Jesus ever had to defecate or urinate. Did the Christ sweat? Could he produce semen? These were questions that naturally occurred to boys just on the verge of discovering their own bodies.

Serrano’s art often used bodily fluids, like milk or semen or urine, as reminders of the humanness of the god-become-man. I met with Serrano when I was an art critic in Phoenix, and there was no mistaking his sincerity. “Maybe if Piss Christ upsets people, it’s because it gives some sense of what the crucifixion actually was like, he said. “I was born and raised a Catholic and I’ve been a Christian all my life. The piece was intended as a serious work of Christian art.”

If there was no doubting his sincerity, we may still question his naïveté over whether the public would easily understand. Most people have a rather lumpen and literal way of understanding figurative or symbolic imagery. A picture of a house should be a house, dammit. But artists, on the whole, are more interested in the things undefined. That could be color, line, shape, scale; it could be symbolism; it could be what the viewer brings to the experience.

Ultimately, you will get the most from the art if you forget what you know and attempt to see what is actually happening before you. As Robert Irwin famously said, “Seeing is forgetting the name of the thing you are looking at.”

One final note: An awful lot of current art is awful, puerile, badly crafted, poorly thought out, and just plain ugly. Of course, it was the same a hundred years ago. I am not defending it as good or important art. And everyone has their own taste; you are free to like or hate any art you want. I am not making an argument that any of this art is genius that will last through the ages. Please, like what you like.

But understand that the artist is very, very rarely just trying to trick you. They tend to be a very serious and thoughtful lot. They are artists because the see things and think things normal people don’t. And if you in turn take seriously what they have made, you may discover something that will enrich your life.

Click on any image to enlarge