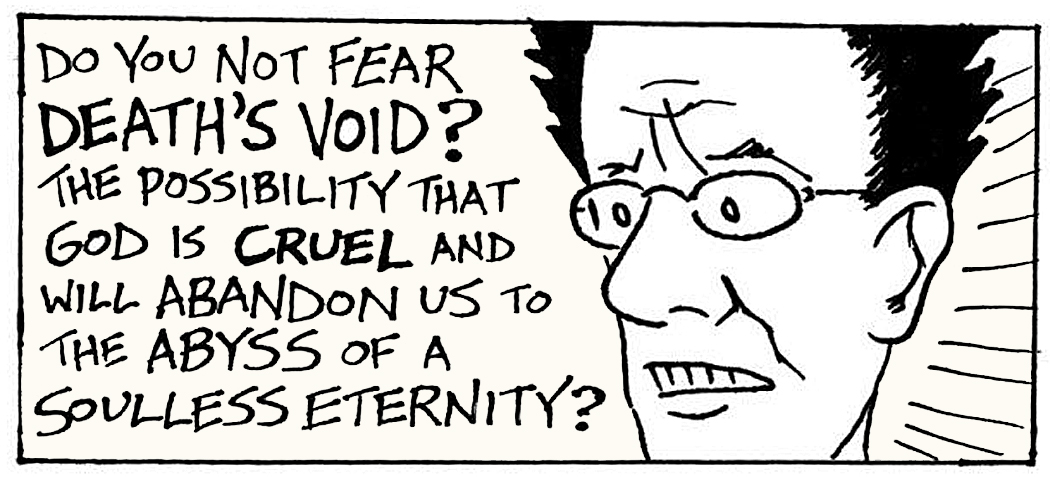

Until relatively recently, 20th century concert music was a tough sell. It had the reputation of being dissonant, noisy, difficult, and unpleasant. It was a century that began with Arnold Schoenberg dispensing with harmony and Igor Stravinsky upending rhythm, followed by a World War that knocked the complaisance out of any rational being and told us that the coming century was going to be anything but calm and easy.

A number of composers felt that music needed to reflect the mood of the angst-ridden age.

But even Schoenberg admitted “There is still plenty of music left to be written in C-major.” He didn’t believe his 12-tone revolution would destroy all tunes to come, but was simply a logical conclusion to music history from Bach through Wagner, from tonality through chromaticism to atonality. And we shouldn’t blame poor Arnold for all the dreary ruckus that followed: His own music is quite emotional and beautiful, even if it often requires some serious commitment from his listeners.

He was right about one thing certainly: There was plenty of music written in C-major, throughout the century. And F-major and D-minor. In fact, most of the music written in that century was based on familiar scales, albeit with plenty of playing around and trying new ways to use them.

It’s just that the music-industrial complex, so to speak, was hijacked around mid-century by a clutch of academically-minded composers — the “Darmstadt Mafia” — insisting that serialism was the only music to take seriously, and that the more unlistenable it was, the greater it must therefore be. (Some of these composers did write interesting music in that style — it wasn’t a complete loss — but they looked down their noses at anything that might stink of a tune.)

And so, contemporary music turned its back on the concert audiences and those composers wrote only for other composers of their ilk, and audiences shrunk from any concert program that insisted they listen to the stuff. Modern music acquired a very bad reputation.

But I find that after 60 years of concert-going and music absorption, I listen to 20th century music more than that of any other era. It is music that speaks directly to me. Oh, I listen to bunches of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms and Tchaikovsky, but the plurality of my music listening edges to the century in which I grew up.

So, I wanted to create a list of representative compositions from the century in question and present them as a course in great music that anyone can listen to and enjoy.

I went through my collection of thousands of CDs and chose 30 pieces to offer. I listened to each one, in order, to refresh my memory — and to flat out enjoy them all over again.

The roughly chronological list begins with a surprising entry. Most people think of Ives’ music (if they think of it at all) as noisy, crashing, impish tomfoolery. But Ives was a well-trained musician, with a degree from Yale University. His Symphony No. 2 is pretty tame, except for his borrowing of familiar popular tunes, and a raspberry at the end.

Here is my list:

1900-1920

Charles Ives (1874-1954) — Symphony No. 2 (1902; premiered in 1951) (42 minutes long). Performance listened to: Eugene Ormandy, Philadelphia Orchestra, recorded 1973.

Ives studied under the respectable, if stuffy Yale professor Horatio Parker, and after graduating in 1898, began working on his second symphony (the first was his senior thesis composition for Parker) and included bits from Camptown Races, Turkey in the Straw and Columbia the Gem of the Ocean run through a kitchen blender. He finished Symphony No. 2 in 1902, although, with Ives, he was never completely finished and continued tinkering until his death in 1952. The symphony wasn’t premiered until Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic played it in a radio performance in 1951. The house-bound but still cantankerous Ives heard it on his radio in Connecticut and his response was that he spit.

I listened to Ormandy’s version from 1973. The recordings listed here are not my choices as “best” — although they are all good — but merely the ones I had to hand when I started this project.

Frederick Delius (1862-1934) — On Hearing the First Cuckoo of Spring (1912) (7 minutes long). Performance: Thomas Beecham and Royal Philharmonic, recorded 1958.

Delius’ score instructs, “With easy flowing movement,” and the quiet, peaceful evocation of the countryside (presumably English) and its birdcalls, it is a calming balm for a tussled soul. Originally, it was one of Two Pieces for Small Orchestra, the other half being Summer Night on the River. Beecham championed the composer’s music and his performances of the music are definitive.

Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) — Nights in the Gardens of Spain (1916) (21 minutes long). Performance: Arthur Rubinstein, piano, Ormandy, Philadelphia Orch., recorded 1969.

Falla was an Andalusian composer and the quasi-Impressionist Nights in the Gardens of Spain functions as a kind of piano concerto, with three movements, each describing a different Andalusian garden. Rubinstein heard it first soon after its premiere in 1916 and performed it regularly after that.

Serge Prokofiev (1891-1953) — Classical Symphony (1918) (13 minutes long) Performance: Ormandy, Philadelphia Orchestra, recorded 1961.

Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1 is the Sara Lee of symphonies: No one doesn’t love it. It is a jaunty, energetic gloss on the Classical-era symphonies of Haydn, seen through the “wrong-note Romanticism” of the composer’s style.

Gustav Holst (1874-1934) — The Planets (1918) (50 minutes long)

Performance: Ormandy, Philadelphia, recorded 1975.

Marketed as “space-age music,” the intent of Holst’s seven-movement suite is astrological, not astronomical, and each movement is a musical description of a psychological type. It has become enormously popular, and it has been recorded more than 80 times, first in 1926 with the composer conducting.

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) — Pulcinella (1920) (39 minutes long) Performance: Claudio Abbado, London Symphony Orchestra, recorded 1979.

Stravinsky took some old compositions by 18th century composers and reworked them into bright, colorful Stravinskian cogs in what Leonard Bernstein once called “Uncle Igor’s Asymmetry Machine,” giving them new life as a ballet score, complete with voices.

1920s

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) — The Lark Ascending (1921) (16 minutes long) Performance: Zina Schiff, violin, Dalia Atlas, Israel Philharmonic, recorded 1989.

Poet George Meredith wrote of the lark in his poem from 1881, “He rises and begins to round, He drops the silver chain of sound…” and Vaughan Williams gives us the violin and orchestra version, with the British pastoral, And whose primary intent seems to be the creation of simple beauty.

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) — La Création du Monde (1923) (17 minutes long) Performance: Simon Rattle, London Sinfonietta, recorded 1986.

European composers began hearing jazz and they loved it. Milhaud even moved to Harlem for a while, to soak it all up. One of the best translations of jazz to the classical idiom is his Création du Monde, with its resonant saxophone solo at the beginning.

Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) — Pacific 231 (1923) (6 minutes long) Performance: Charles Dutoit, Bavarian Radio Symphony, recorded 1985.

A steam locomotive begins to move, gathers speed, churns along and comes slowly to a stop, in this propulsive tone poem to modernity. Trains have been a theme in 20th century music, from Duke Ellington’s Happy-Go-Lucky Local to Villa-Lobos’ Little Train of the Caipira. Chug-chug.

Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) — The Pines of Rome (1924) (20 minutes long) Performance: Ormandy, Philadelphia, recorded 1958.

There were no flying humpback whales in Respighi’s original score; blame Disney for that. But what you do get are rousing tunes and some spooky catacomb music, with a grand finish, the kind that gets you out of your chair cheering.

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) — Symphony No. 7 (1924) (22 minutes long) Performance: John Barbirolli, Halle Orchestra, recorded 1966.

Sibelius’ final symphony is also his shortest, being in one movement, but by some accounts his best. My old teacher said when he was young, he wanted to play the French horn, because it had all the great solos. But he wound up with the trombone, which “only plays supporting material,” he said. But in this symphony, the trombones get the big tune, the one you will most likely remember and hum after it’s over.

George Gershwin (1898-1937) — Piano Concerto in F (1925) (32 minutes long) Performance: Andre Previn, piano and conductor, Pittsburgh Symphony, recorded 1998.

Who was Arnold Schoenberg’s favorite composer in America? His frequent tennis partner, George Gershwin, who was much more than a Tin-Pan Alley songster. At the time, there was a big rush to figure out how to incorporate jazz into concert music. Well, here’s how.

Leos Janacek (1854-1928) — Sinfonietta (1926) (23 minutes long) Performance: Claudio Abbado, Berlin Philharmonic, recorded 1989

What grabs you at first are the 14 trumpets, four horns, trombones, tuba and euphoniums. But the rest of the music pops with chunks of memorable tunes, piled like crabs in a bucket, and the way Janacek uses musical “jump cuts” to go from one to the next.

1930s

Howard Hanson (1896-1981) — Symphony No. 2 “Romantic” (1930) (29 minutes long) Performance: Gerard Schwarz, Seattle Symphony, recorded 1989.

All those American symphonies written in the 1930s and ’40s have been largely forgotten, despite their quality, but when Ridley Scott used Hanson’s music during the closing credits of his 1979 film Alien, it resurrected this “Romantic” symphony, which developed a second life. Scott did it without Hanson’s permission, which pissed off the composer, but Hanson never sued, probably because of the boost it gave his music with audiences.

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) — Piano Concerto in G (1932) (21 minutes long)

Performance: Samson François, piano, André Cluyten, Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire, recorded 1959.

The French were just as taken with jazz as Americans were, in the 1930s. Lots of composers attempted to weave the syncopations and blues notes into their work. Ravel did it twice, with each of his piano concertos. But this one has a slow movement of such hypnotic ethereal peaceful beauty that you feel in a trance, broken by the explosion of the finale.

Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936) — Saxophone Concerto (1934) (14 minutes long) Performance: Marc Chisson, saxophone, José Serebrier, Russian National Orchestra, recorded 2010.

Glazunov was exiled to Paris when he wrote his own jazz-influenced concerto for alto saxophone, which is perhaps less jazzy than Russian, but is nevertheless probably the best concerto ever written for the instrument.

Samuel Barber (1910-1981) — Adagio for Strings (1936) (8 minutes long) Performance: Ormandy, Philadelphia, recorded 1957.

Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin made a movie in 2003 titled The Saddest Music in the World, about a contest to find such music. Well, he needn’t have worried: Hands down, the winner (ignored by the film) is Sam Barber’s orchestral transcription of the slow movement of his string quartet. Unbearably beautiful, it is near impossible to hear it without weeping.

Colin McPhee (1900-1964) — Tabuh-Tabuhan: A Toccata for Orchestra (1936) (17 minutes long) Performance: Howard Hanson, Eastman-Rochester Orchestra, recorded 1956.

McPhee heard Javanese gamelan music on a visit to Bali and then moved there. He became an ethnomusicologist as well as composer and wrote his own gamelan-influenced music full of the percussive tintinnabulation that is so catchy. Tabuh-Tabuhan is his most popular work, meaning it’s pretty much the only piece most people know, McPhee having otherwise fallen into undeserved oblivion.

Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) — Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5 (1938) (7 minutes long) Performance: Bidú Sayão, soprano, orchestra of cellos, conducted by Leonard Rose, recorded 1949.

The composer was fascinated by the long-line melodies that Bach sometimes wrote and came up with his own. Originally a single movement for soprano and eight cellos, it was recorded that way in 1949 by Bidú Sayão in a recording of singular beauty and power. It is very difficult, as the final third of the movement is required to be hummed through the nose, with the mouth closed, and ending on a nearly impossible octave leap. He later wrote a second movement, but this recording of just the first is so exceptional, it has to be heard.

1940s

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) — Symphonic Dances (1940) (35 minutes long) Performance: Leonard Slatkin, Detroit Symphony, recorded 2002.

It is sometimes hard to realize that Rachmaninoff is essentially a 20th century composer. And all his later music (the Paganini Rhapsody, Third Symphony and this, the Symphonic Dances) is rife with irony and astringency. Heart no-longer on sleeve, but with unforgettable tunes and absolutely brilliant orchestration. These Dances were his final composition, and for my money, his best.

Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978) — Violin Concerto (39 minutes long) Performance: Ruggiero Ricci, violin, Anatole Fistoulari, London Philharmonic Orch., recorded 1956.

Khachaturian doesn’t get much love. His music is catchy, tuneful, and never very deep. And so, the Music-Industrial Complex (i.e. German musicographers) turn their noses up. But what is music if not melody? And bright arresting orchestrations. At some point, the world will catch up with Khachaturian and realize there’s room for music that is simply enjoyable, with no philosophical baggage attached.

Bela Bartok (1881-1945) — Concerto for Orchestra (1943) (47 minutes long) Performance: Fritz Reiner, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, recorded 1958.

Bartok was ill and in hospital when Serge Koussevitzky visited him in 1943 and presented him with the commission for this orchestral masterpiece. Bartok had fled Hungary because of the war and was dying of leukemia, but he got out of bed, left the hospital and wrote what became his most popular work, essentially his symphony, a five movement piece featuring brilliant solo work for pretty much everyone member of the orchestra. He died two years later.

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) — Symphonic Metamorphosis on a Theme by Weber (1943) (22 minutes long) Performance: Wolfgang Sawallisch, Philadelphia Orchestra, recorded 1994.

So much of the century’s music seems to have been written as gloss on music of the past: Stravinsky’s Pulcinella, Rachmaninoff’s Paganini Rhapsody; Prokofiev’s Classical Symphony — even Ives’ symphonies constantly quote old tunes. Hindemith’s most popular piece (popularity not having followed the composer into the 21st century) is his recasting of melodies written by Carl Maria von Weber. It is brilliant. Hindemith should be played more.

Aaron Copland (1900-1990) — Appalachian Spring (1944) (24 minutes long) Performance: Leonard Bernstein, New York Phil, recorded 1961.

When the century’s music seemed to becoming more intellectualized and abstruse, Aaron Copland developed a simpler, more audience-friendly style, best captured in this hugely popular ballet score. Copland became the American composer. Originally for a chamber group, the orchestral version is now a standard concert piece.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957) — Violin Concerto in D (1945) (24 minutes long) Performance: Jascha Heifetz, Alfred Wallenstein, LA Philharmonic, recorded 1953.

Korngold was a prodigy once compared to Mozart, came to America and became the Ur-film composer (three Oscar nominations). But after WWII, he tried to reestablish his bona fides as a serious composer, with this most beautiful of 20th century violin concertos, now in the standard repertoire. It begins with a startling two-octave run in just five notes. Championed by Jascha Heifetz, it is now in every serious violinists repertoire.

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) — Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Purcell (“Young People’s Guide to the Orchestra”) (1946) (17 minutes long) Performance: Ormandy, Philadelphia, recorded 1974-1978.

Another gloss on old music, Britten wrote his “Young People’s Guide to the Orchestra” as a means to teach about the instruments, along with narration. But much better without the sometimes condescending talking, it is a brilliant showpiece for the orchestra.

1950s

Joaquin Rodrigo (1901-1999) — Fantasia para un Gentilhombre (1954) ( 22 minutes long) Performance: Manuel Barrueco, guitar, Philharmonia Orchestra, Placido Domingo, conductor, recorded 1996.

Rodrigo reworked the music of 17th-century Spanish composer Gaspar Sanz, in another retro work, mixing the old dance music with eminently listenable modern orchestra colors.

Alan Hovhaness (1911-2000) — Mysterious Mountain (Symphony No. 2) (1955) (19 minutes long) Performance: Fritz Reiner, Chicago, recorded 1958.

Hovhaness wrote 67 symphonies and sometimes it is hard to tell them apart: His style was his style and he stuck to it. But his second symphony, called Mysterious Mountain, is his most popular and a perfect introduction into what you get with this Armenian-American stalwart.

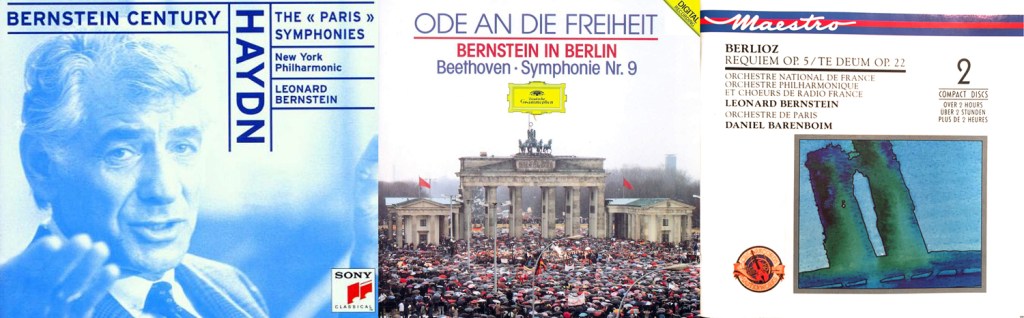

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) — Candide Overture (1956) (4 minutes long) Performance: Leonard Bernstein, London Symphony Orchestra, recorded 1989.

The best overtures are bouncy, tuneful, catchy and bright. It is almost as if Bernstein had absorbed all of the best overtures of the past and wrapped them up in his ultra-brilliant Candide overture, certainly the composer’s most-often programmed work.

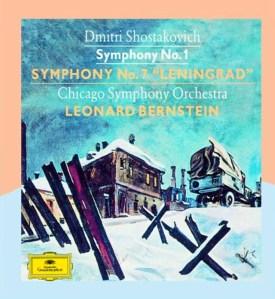

Dimitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) — Piano Concerto No. 2 (1957) (20 minutes long) Performance: Christina Ortiz, piano, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Vladimir Ashkenazy, cond., recorded 1989.

The composer write this late concerto for his son, Maxim, to perform. He didn’t have a very high opinion of the work, thinking it a throw-away piece, but it is his most accessible concerto, with a second movement nearly as hypnotic as the Ravel. It may be lightweight Shostie, but it is nothing to sneeze at.

In going through these recordings, some of which had to be dug up out of the lower shelves of my collection, I have redoubled my admiration for the music of the previous century.