My attraction to Manzanar was initially artistic, not political.

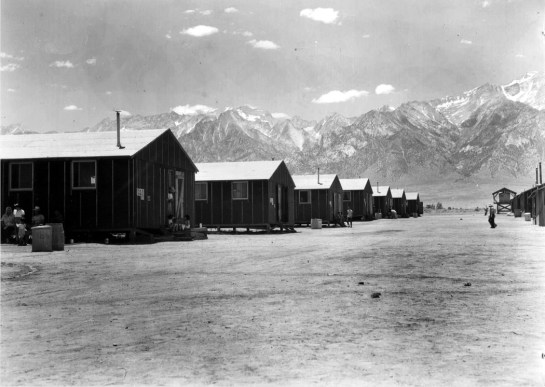

The 500-acre site in California’s Owens Valley on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada is now a dusty spot of desert under the snow-capped peaks, but in 1943 it was home to 10,000 Japanese-Americans detained under federal order in a concentration camp built there, one of 10 such camps in the American West.

That year, it was visited by photographer Ansel Adams, who was invited to make a series of photographs of camp life. I had seen prints of those photographs while doing research at the Library of Congress, where they are stored, and had long wondered about the place.

”My first impression of Manzanar,” Adams wrote in his autobiography, ”was of a dry plain on which appeared a flat rectangular layout of shacks, ringed with towering mountains. … row upon row of black tar-paper shacks only somewhat softened by the occasional greenery.”

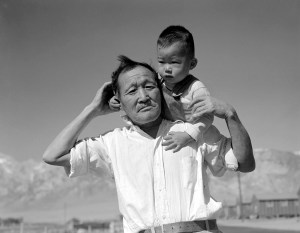

Most of the photographs he made are of the people, their homes and the social lives they maintained under impossible circumstances. But he also found something redemptive in the landscape.

”I have been accused of sentimental conjecture when I suggest that the beauty of the natural scene stimulated the people in the camp. No other relocation center could match Manzanar in this respect, and many of the people spoke to me of these qualities and their thankfulness for them,” he wrote.

And the single most famous image from Adams’ time in the camp is his Mount Williamson, Sierra Nevada, from Manzanar, California. It was prominently featured in the Museum of Modern Art show ”The Family of Man” in the 1950s, with its foreground of gargantuan boulders and background of sunlight breaking through a storm over the mountain peak. If ever there was a photograph meant to evoke the spiritual power of landscape, this is it.

So I was drawn to Manzanar to see the land. Certainly nothing was left of the camp, I was certain.

And the only thing that gives away the location of the camp is a stone sentry booth off the side of U.S. 395 about 15 miles north of Lone Pine. Behind it, all you see at first glance is gravel, dry grass, mesquite trees and clumps of datura wobbling their coarse white lace in the breeze.

But as soon as you drive into the camp and crawl along the old dirt roads, you discover what the decades have tried to obscure: flat concrete foundations of barracks, some weathered lumber littering the ground and the odd sight of water-system standpipes poking up like leafless shrubbery in the emptiness.

Walking through the old foundations, you discover broken bits of dinner plates and an occasional fork with its tines splayed. In one plaza area between the concrete ruins, there was a 5-foot mound of earth ringed with stones. It had been a Japanese rock garden built by the internees.

Above the camp, Mount Williamson still looks impressive although nothing in nature ever looks quite so impressive as it does in Adams’ prints.

And the reality of American politics is sometimes less impressive than it looks in the Constitution. Here in Manzanar, American citizens were locked up for no reason but their race.

When Adams published a book, Born Free and Equal, of his Manzanar photographs in 1944, copies were actually burned by what Adams called ”reactionary groups with racial phobias and commercial interests” who questioned his loyalty and patriotism.

I became adult as the Vietnam War raged both here and in Asia, and I recall many of the same sentiments expressed then.

And as I left the camp, I poked through the sentry booth, which is filled with 50 years’ worth of graffiti, most of it in Japanese and left by those who were detained there and now by their descendants, who often come back to visit.

A young Japanese man pulled up on his Kawasaki while I was there and started photographing the booth interior. He spoke almost no English, but when I asked him if he could translate the words, he told me that most were names.

I pointed to one set of characters carved into the woodwork around a window, and he told me it was the Japanese transliteration of the name Clark.

In 1992 Congress designated Manzanar as a National Historic Site. It was the 50th anniversary of Franklin Roosevelt’s executive order authorizing the internment.