Delmarva Peninsula

When I was a kid, most things in the world just were. Everything was normal, even if it wasn’t. People lived in houses, roads were paved, families had a mom and dad. And, for a kid, parents were just parents; I never gave much thought to why they did what they did. It wasn’t even that if they did something, they must have had a reason. They just did things. They were Mom and Dad, and as children, me and my brothers just followed along. As a child, the world is a given.

It’s hard to recall that state of affairs, when things happened because they happened. That they might have done things for the abstract good of their children never dawned on me. Of course, now that I am old, I look back and realize how much they did for us, things they didn’t have to do, or things they probably would have preferred to do some other way, including some other things they might have wanted to do with their sparse vacation time.

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

But one of the things they did for us was travel. When we had our summer school vacations, Mom would pore over various brochures, magazine articles, and roadmaps and carefully plan routes to drive and sites to take in, and then, when it came time, we would load up the car and take off. We went to Washington D.C., to Niagara Falls, to Fort Ticonderoga, to Gettysburg — and many spots in between. Only later did I come to understand there was a purpose to these vacation trips. they chose these things to expose their children to history, geography, politics and to let us see what was possible outside suburban New Jersey. Travel was part of our education.

Back when they were children, they didn’t get to travel. They both grew up in northern New Jersey and neither had more than a high school education. Dad’s family was heavily religious and didn’t approve of having fun, and Mom had to raise her two younger siblings after her father died when she was still in grade school and her mother had to find work in New York City. And so, the worlds they grew up in were limited.

German gun, Omaha Beach, Normandy, France

But when my father was drafted in 1940, he was sent to Camp Wheeler in segregated Georgia. He didn’t talk much about his army life, but he did express shock at discovering the pervasiveness of racial discrimination. And then he was sent overseas after D-Day to France, Czechoslovakia and Germany and found that other peoples had various ways of making a decent life. His horizons were involuntarily expanded.

When they got married, shortly after the war, they felt it was important to broaden their children’s horizons, too, and to make sure we got the best educations. There was never any question that their kids would go to college. (I was told that when I entered second grade, I asked if that meant I could go to college “next year?”) Education was Priority One. Travel was a component of that.

Kristiansand, Norway

Later, when I was in high school, they made it possible for me to go to Europe, accompanying my immigrant grandmother to her birthplace in Norway, and to take a bus tour through France, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. A few years later, my younger brother, Craig, was sent off on a similar trip.

Mark Twain famously said that “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.”

The vast bulk of the MAGA world, it seems to me, is made up of those who have never ventured far from their birthplace. If they had seen how others live, they would not accept the lies.

Cairo, Illinois

Travel, then, has pretty much always been an essential part of my life, and having become an adult — at least as quantified in years accrued on the planet — I have continued the habit instilled by my parents. Education wasn’t only in books; I read Huckleberry Finn, of course, but I’ve also been to Mark Twain’s childhood hometown of Hannibal, Mo., and to what remains of Cairo, Ill. I’ve driven along the entire length of the Mississippi River, from Lake Itasca, Minn., to the Venice Marina where the road ends in Louisiana.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia

It is rare to mention a place I haven’t been in the continental United States or provincial Canada. Big Sur; Mt. Katahdin; the Everglades; El Paso;, the Union Pacific Bailey Train Yard in North Platte, Neb.; Hudson Bay; Halifax, Nova Scotia; the Tehachapi Loop in California; the Sturgis Rally in South Dakota; even Glacier Bay in Alaska.

Glacier Bay, Alaska

Believe me, I can be quite irritating, when someone mentions some far-off place and I chime in, “Oh, yeah, I’ve been there. Had a great Po Boy sandwich in a little shack along the road in Pecan Island.” Which is a tiny community along the southernmost road in Louisiana. Or “Abiquiú? Yes, we visited Georgia O’Keeffe’s place there.” I am slowly learning to keep my yap shut.

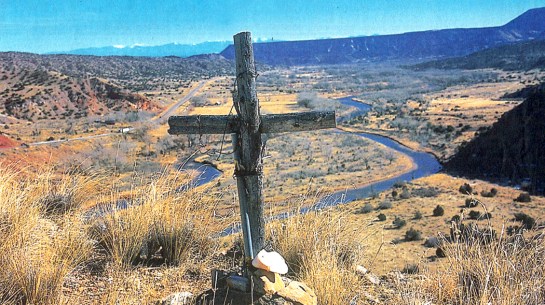

Red Mesa, Navajo Reservation, Arizona

I’ve been to every state except Hawaii, and most of them many times, and every province in Canada, save only Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. I’ve lived in four corners of the continental states, growing up in the Northeast, moving to the American South, then to Seattle in the Northwest, and spending 25 years as a writer in the Southwest. Each move gave me a chance to explore all the territory nearby, often in some detail (There’s hardly a square meter of Arizona that I haven’t been to. Go ahead, name something obscure: Ajo? Red Mesa? Tumacacori? Freedonia? Gadsden? Quartzsite? Check, check, check, check, check and check.)

Cape of Good Hope, South Africa

I’ve been to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa and to Marylebone Road in London; I’ve been to the Chartres Cathedral, and to the bull ring in Arles, in Provence. My late wife and I went back to France many times, and drove to all six corners of “The Hexagon.”

And so, yes, I’ve been to the D-Day beaches at Normandy and to the bomb craters still evident in Verdun, to the cave art along the Vézère Valley, to the paleolithic menhirs and dolmens near Locmariaquer.

Dolmen, Locmariaquer, Brittany, France

I’ve visited the Museum of Questionable Medical Devices, the Museum of Jurassic Technology and the Hammer Museum of Haines, Alaska.

And it has all been an education. I certainly learned that the omelet I get at Denny’s is a pale mutilation of the rich, creamy offering you can find at any neighborhood cafe in Paris.

O’Keeffe Country, New Mexico

Of course, I’ve also learned how little of the world I’ve actually seen. I have so much of the non-European inflected planet yet to see, although, at my age, it’s almost certain I will never get to Japan or the Seychelles or Samoa. Just as, no matter how many books I’ve read, there is always a hundred times more books I will never get to read, and not enough time left even to put a dent in that list. I keep trying.

Windsor Ruins, Mississippi

And so, in addition to bragging about all the places I’ve been, I am shamed by all those places I have not gone to, just as all the art I haven’t seen, all the books I haven’t read, all the music I have never heard. But I think that it is only because of all I have read, seen, and heard, that I know enough to feel the gaping holes in my education.