I am a cat person. I’m not sure how that happened. I didn’t grow up with cats — or dogs — for that matter. My father hated cats. He wasn’t fond of dogs either, but that was more like indifference; he actively disliked cats. Somehow, I grew up differently. Through most of my adult life, there have been cats in my household, sometimes a full clowder.

People seem to be divided between dog people and cat people. I’ve written about this before. Dogs are simple. You can count on them, yes, but they seldom surprise you. Cats live in an infinitely more rich and complex world. They have an inner life, which is inscrutable. Dog people like dogs because they are trustworthy and dependable. Cat people find this rather boring. We like to be surprised by what our feline overlords are up to.

My first cat came to me in the early 1970s because I was friends with three women who lived on Cedar Street, in Greensboro, N.C. They had a cat named Trevose, who was boss of the neighborhood. He sired a kitten on a semi-feral cat named Mama Kitty and I inherited the progeny.

The three women, known collectively back then as “The Girls,” had been on a backpacking trip through Great Britain and had camped in Cornwall at a place called Trevose Head, hence the name of the sire. His son, then become my cat, was given the name Head, which would have been his name on his driver license, if cats could drive. But we soon nicknamed him Widgie. And that’s the name that stuck.

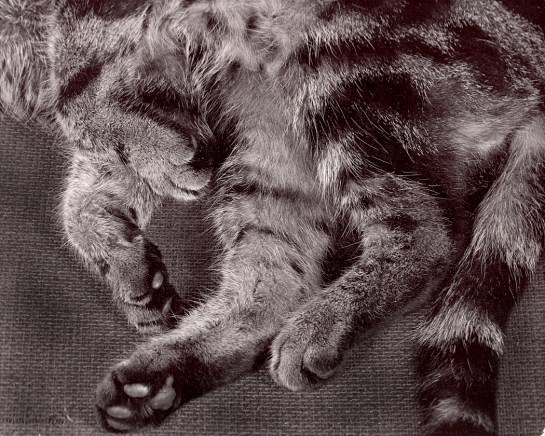

Widgie grew to be a great bruiser of a cat, with a face as broad as Clark Gable’s. He became the neighborhood “capo,” the cat to whom others came for favors. He survived many fights, winning them all and grew tougher and brawnier with each.

He showed all the usual feline behavior that we laugh at and love cats for: chasing phantoms from room to room, staring at blank spots on the wall as if watching the most fascinating theater, slurping himself through a handful of catnip and looking at me all droop-eyed with a sliver of tongue in the cleft of his upper lip.

It was not unusual for him to scratch at the back door to be let in, and when I came, he might carry the dead body of a vole or sparrow to drop at my feet as if it were a present, or perhaps his kitty version of the rent he owed.

And he had the usual vocabulary of odd catspeak. I rarely heard the classical “meow,” but often heard the “ack-ack” when he spotted a bird out the window, or the “gmorph” when he looked up at me as if to say, “Ain’t life peculiar.”

I often mimicked his talk back at him, but once made the mistake of saying, “Brrrrrttt” to him, which means god-knows-what in cat language, but sent him into the air with his claw swiping at my nose as if I had insulted his mother.

Another time, playing with him, I chased him around the house. If he got away, he returned to find me again so I would renew the chase. I finally got him cornered on the second floor — literally cornered so that he had nowhere to go. He looked both ways to find an alternative, then, when none appeared, sprang up in the air at least double his length with his arms held wide as a crucifix, with his claws stretched open and a scream in his mouth. But he attacked straight up, not at me. It so startled me that I first backed off, then fell backwards laughing. I had never seen him so fierce.

Then, there was cat bowling. When we lived in Virginia Beach, our apartment had a long hallway with smooth wooden floors and I would toss Widgie down the length of it, watching him try to get traction on the wood with his claws. He would slide all the way to the end and then race back to me to do it all over again. He loved it.

I mention these things because I want to talk about how he became a member of the family. It isn’t that I didn’t know he was an animal. I did, but that simply didn’t matter: He was the animal member of the family.

I know it is the same way for many, perhaps most pets. But the point I want to make is that there is something that transcends the sentimental attachment we have for “Little Puss,” or Rover. There are people who go all soft and goofy over animals; they are not, in fact, treating them as a member of the family, but as some idealized object of a rather sappy affection. People don’t treat real family members that way.

But this particular cat was more like an uncle or brother. I came to know his habits, both good and bad, and accepted them all; he in turn, forgave me some of my faults.

Nutlets

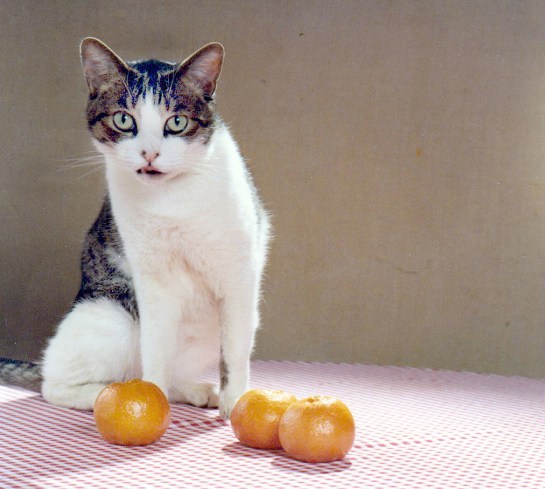

The second cat that entered the family was a patchwork piece, more normal sized than the big boy. His official name was Undifferentiated Matrix, but one morning my girlfriend and I woke up to find him mushling us, facing our feet and she said, spontaneously, “Ooh, look at his little nutlets.” And that became his name. Nutlets.

The naming of cats is important, as Old Possum told us. The name we give them initially often doesn’t hold up, and usage stamps them with a new one. So, Undifferentiated Matrix became Nutlets. We added a furry, completely gray kitten once. He was named Brahms, but called Fuzzbox.

My sister-in-law, Deborah, had a stray she named Chicago Transit Authority, although he became just Chicago. My favorite was a cat owned by a pair of friends in Greensboro, who they named Samuel Maybe Gompers.

Pachebo

There are traditional names for kitties, but even then, there might be some feline irony involved.

“At the farm, we had a white cat we called Snow,” says Deborah, about a time in the 1980s. “Being sophisticates, you will know our name did not refer to the weather.”

Genevieve, my friend Stuart’s wife, once had two cats. A black one, named Snowball, and a white one named Midnight.

Deborah still has two, a ginger named Saffron and a tabby named Emily.

Emily

The champ, though, must be our friends in Maine, Alex and Mary Lou, who over the years have had loads of cats in their care, among them: Pachebo and Redburn. “Let’s see … Hecate, Thunderpaws, Tycho, Chicory, Machimos, Serenity, Justin, Vesta, Quiffen, Q.2, Oscar, Minkey and Fred — I think that’s all.”

Minkey

Thunderpaws was special. I lived with Alexander and Mary Lou when they had a great old house in Summerfield, N.C. — a house with no central heating, just a wood stove in the kitchen.

Thunderpaws was an orange giant who had a talent for losing body parts. He had only the stump of a tail when I first knew him. Later his ear got mangled and he lost an eye, like a pirate cat. Or maybe Popeye. He was called Thunderpaws because, unlike most of his species, he clomped rather heavily when he walked. Thud-thud-thud. He was also more like a dog than a cat in temperament. He was a cuddly little monster and loved to be loved. His purr vibrated his whole body.

Saffron

A house will not usually put up with two alpha male toms, and my Widgie was the big boy, but Thunderpaws was also top cat. We had to keep them separate. When Widgie was loose in the house, Thunderpaws was relegated to the basement or outside. When T-paws was feeding in the kitchen, Widgie was locked in my bedroom. But the inevitable happened.

There was a battle royal, which my friends still talk about once in a while over dinner. One day, Thunderwunder managed to sneak into my room while I wasn’t there. The two cats fought like the Act 2 climax of a Verdi opera, a sort of feline Achilles and Hektor. Alex heard the squall and pounding thuds and by the time he got to the room and opened the door, he told me, the air in the room was snowing cat fur and on the floor staring innocently at him, he saw the two of them, an orange cat with a gray mustache and a tabby with an orange mustache. It may have looked like a standoff, but subsequently, Thunderpaws always “defurred” to my Widgie.

By the time Widgie was a very old cat, I had to care for him like an aging parent, performing those humiliating services — humiliating certainly for a prideful cat and humiliating to me to have to see — such as cleaning up after him and changing bandages.

He eventually died in the house while I was away at work. When I came home in the evening, my wife met me at the door and broke it to me gently.

I cried over the death of that cat as I have cried few times in my life. He had been with me for 15 years and had been my most constant companion. He saw me through two and a half marriages and residences in several states.

Saffron

Now, I said I am not a sentimental man. I don’t believe in creating sham emotions when they don’t exist, or glorifying trivial ones. Yet, I know that that cat and I shared something.

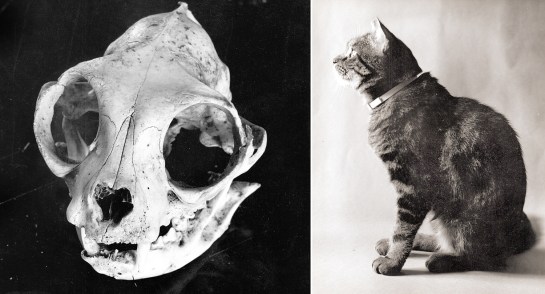

We buried the cat in the marshy woods of Mackay Island National Wildlife Refuge on Knotts Island in his home state of North Carolina. My wife, Carole, insisted we leave him with a paring knife so you would have a tool in the next life. I came back to the site about a year later and found his tiny, wasted skeleton under the brush where we left him. I collected his skull, put it in a box and to this day keep it on a shelf in my library.

I also have his photograph — his great, broad Clark Gable face — as a screen saver on my Macintosh.

Ultimately, though, what I think I mean when I say he was a family member is that I learned from him. It is one of the prime functions of family: We model behavior on our parents, learn to be better men when we marry, learn patience and a sense of the future with our children. It is an emotional and almost mythical relationship we have with family, unlike that we have with those we meet in business or career.

Emily

And from my cat, I learned a number of things. I learned how to concentrate on a task as though I were defusing a bomb. I learned how to face experience with a certainty I didn’t really possess. I certainly learned the trick of relaxing; I am now a master of it. And I learned, even through his death, how life is a certainty of loss. And all those we love will die and we cannot love them any the less because of it.