Translation is a funky thing. You might think a literal transcription would be best, but language doesn’t work that way.

If we translate Holly Golightly into French, and have her window shopping, the French reader will assume she is looking for a glazier — i.e., shopping for windows. If the original had been in French and we translated it to English as “licking the glass,” we’d assume Holly was more than slightly daft.

You can try to be literal and lose all the flavor, or you can try to find equivalent idiomatic expressions, or you can recast the whole thing, as if you were writing an original from a similar inspiration — your own words for a similar thought.

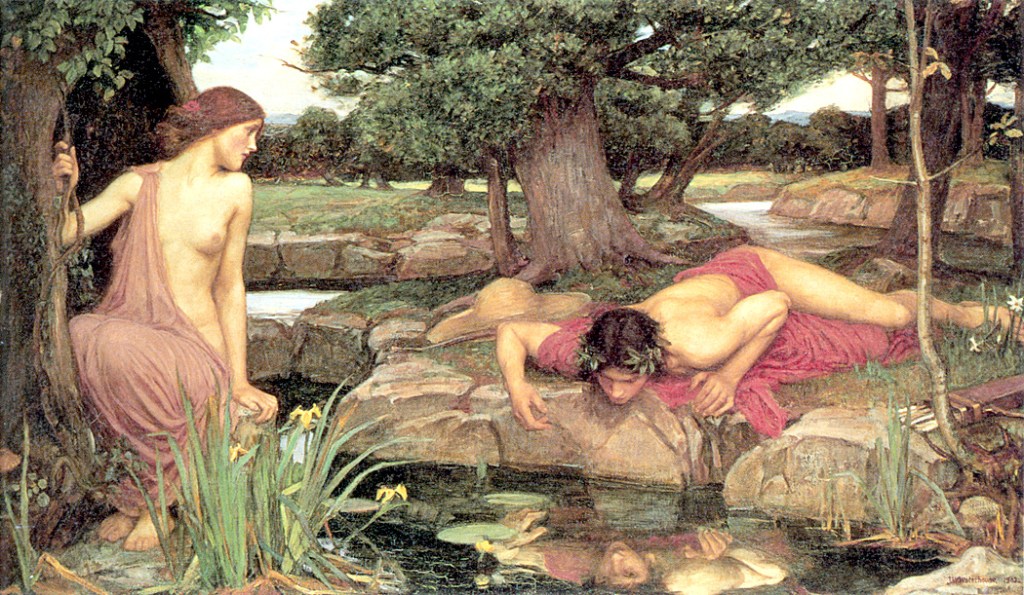

I recently posted a blog entry about various versions in English of Ovid’s epic poem Metamorphoses. (link here).

“It’s amazing that all the translations are so different,” responded a friend. And they are. I have been fascinated with the issue of translation for years, now, and have compared many versions of several works and am also “amazed” at how different they can be.

Most recently, the Ovid comparisons has been obsessing me. And so, I went back to the original to see what I could ferret out about these variations. One discovers that although Ovid’s language moves quickly and simply, there is some ambiguity built in to those words. A translator has to disambiguate the text, and in the process make a single meaning for what in Latin can be multiple.

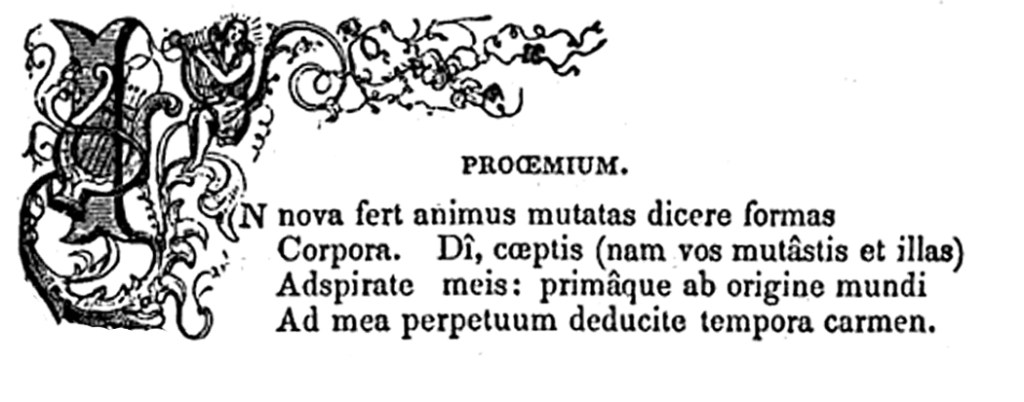

The first four lines of the Metamorphoses, in Latin, read:

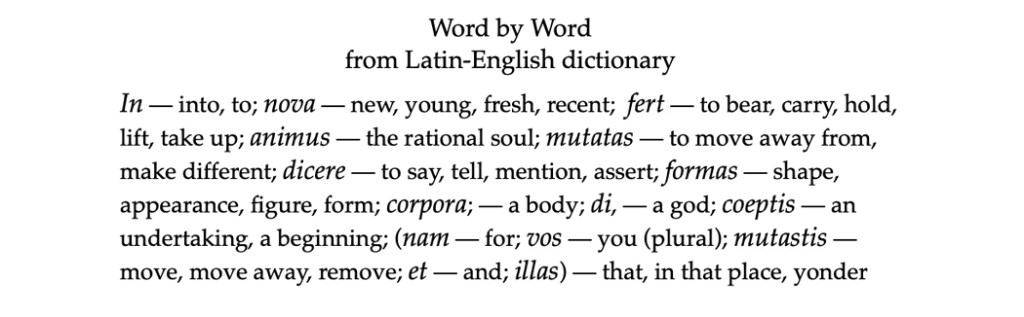

The Latin is alien to English speakers first because word order is not a central concern of Latin grammar. Ovid arranges his sentences according to his metrical choice — Latin hexameter. And that is built around syllable length, not stress. And so if you were to just put down a word-by-word transference from Latin to English, you get, essentially, nonsense.

In 1828, a British publisher printed an interlinear translation, intended to help students in learning Latin. To simplify the project, Ovid’s word order has been shifted to mimic English word order. Thus published, the sense, more or less, becomes clear.

That is: “My-Spirit prompts to tell of forms changed into new bodies. O-Gods (for ye have-changed even those). Breathe-kindly on-my attempts and-carry-down the-continuous song from the-first origin of-the-world to my-own times.”

(The hyphenated phrases are Latin single words that must be broken into multiple words to be rendered in English).

All this is good, and one could easily smooth all this out into very plain English: “My spirit prompts me to tell of forms changed into new bodies. O Gods (for you have changed even those), breathe kindly on my attempts to carry down this song continuously from the origin of the world to my own times.”

And there you have it: Ovid translated cleanly and understandable.

Except.

Except that this version, as plain as it might be, avoids some of the complexities of the Latin, which doesn’t so easily give up its meaning in a one-to-one way with our King’s English. And it doesn’t explain the wide variants rendered by translators from 1567 to our own times.

Over the years, translators couldn’t make up their minds whether bodies were changed into new forms or forms into new bodies. Ovid writes forma into nova corpora. But in English that seems backwards.

It’s been explained as hypallage (a rhetorical trope in which elements are switched from the place expected, as in “the angry crowns of kings” instead of the “crowns of angry kings.” It was a trope often used in Latin writings.) Ovid talks of “forms” changed into new “bodies,” where, in English, we might expect “bodies changed into new forms.” The difference is that in Latin, “forma” describes the “true” shape of something, in other words, the way it was created, such as your body or mine. Ovid is saying that the true shape of his mythological figures are being altered to new, perhaps temporary, bodies — in other words, the new bodies are not the “real” bodies.

In English, we would tend to word it the other way around, so that our “real” bodies are given new “forms.” And so, some translators write it that way, while others maintain the forms-to-bodies version.

This may seem like a trivial thing, but if you grew up with Platonic ideals and they were ripped apart into “false” new shapes, you’d understand what Ovid is getting at here. Of course, he does not make a big thing about it: He expected his listeners (or readers) to understand that the way we might understand “three strikes and you’re out.” It is just buried in the culture. Theirs, though; not ours.

Most English translations really start with anima:

“My spirit prompts” can be understood as “My design leads me” (1899 Riley); “I want to speak about” (1903 Kline); “My mind is bent to tell of” (1916 Miller); “My soul is wrought to sing of” (1922 More); “My purpose is to tell of” (1955 Innes); “My intention is to tell of” (1955 Humphries); “My soul would sing of” (1993, Mandelbaum); “My spirit drives me now to sing about” (2012 Johnston); “My mind leads me to speak now of” (2012 Martin); and most recently, “My spirit moves to tell of” (2022 McCarter).

But of course, the poem really begins with the word “Nova”… “New.” And a few attempt to mimic the Latin word order, approximately. One could attempt something in English, contorting it like a gymnast:

Certainly, that is awkward sounding, and I am not recommending it as a preferred translation. We should want something that moves as cleanly in English as Ovid moves in Latin. Mimicking Latin won’t do that.

But there are other issues, too. You’ll notice I used “weave the thread” of song. Ovid has “deducite” — to lead away, draw out, turn aside, divert, bring out, remove, drive off, draw down. It is used, says one set of notes, to mean to extend like a chain, or, as I have it, “weave the thread,” but more like “add links to links to make up a whole chain” of mythological stories.

You can see the problem here: Which idiomatic Latin usage of “deducite” should you use here — again, without turning the passage into something utterly unreadable.

That chain, and its metaphorical maritime implication is echoed in “adspirate,” which implies a fair wind in the sails, as if the gods were blowing their breath to move ships. These things are not clear in English and are only implied in Latin, but they are there.

The multiple possible meanings of many of these words can bring variation to a potential translation. “Carmen,” for instance, can be a song or a poem — or a prophecy, an incantation, a tune. “Tempora” can be time, or a season, or a duration. “Fert” can be to pick something up, to carry it, to take something up. A translator has to decide what is best meant and how in English to make that clear.

There is a giant ambiguity in these lines that gets very differently translated. When Ovid calls on the gods, he says “nam vos mutastis et illas,” which means, literally, “for you (plural) change (or move, or remove, or move away from) and that (or there, or yonder).” What do you make of that?

In previous centuries, it was taken to mean, basically, “for you gods caused those changes.” And that seems to make sense of it. But beginning in 2001 with Michael Simpson’s translation, many have assumed it is the poem that the gods have changed. “Gods, inspire this poem I’ve begun (for you changed it too)” (2001 Simpson); “O gods (it is you who have even transformed my art)” (2004 Raeburn); “inspire this undertaking (which you’ve changed as well)” (2004 Martin); “inspire my work (for you’ve transformed it too)” (2022 McCarter).

These two interpretations can not both be correct. Ovid is obscure here, and leaves a good deal to the discretion of the translator.

Or to the edition. A translator has to pick among variant texts in Latin, collated by different editors. And the Latin is not completely identical in all of them. Remember, Ovid survives not in manuscripts from Roman times, but from copies made by monks in scriptoria through the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, and when copies are made, mistakes are made. Which is the true version: That is the job of an editor putting together a modern published edition.

Joseph Reed, in his annotations to the new edition of Rolfe Humphries’ translation write of this confusion: “Most manuscripts have ‘for you, gods, changed those [forms] as well’ (nam vos mutastis et illas), which Humphries seems to be translating here, omitting the troublesome ‘as well,’ which has no clear reference. Since the 1970s, most editors prefer to read the slightly different text, ‘illa,’ found in a few manuscripts, which yields the very different sense: ‘for you changed that [undertaking of mine] as well,’ referring to the new direction Ovid’s own poetry now takes from his earlier themes and metrical forms (love elegy) to those of epic-length mythological narrative.”

The difference between “that” and “those” (illa et illas). No matter how you parse it, the original is obscure.

Finally, you must decide what you want in your Ovid. If you are a scholar you want whatever is closest to the poet’s original language, even if it is obscure. And I sympathize with the impulse. But if you are simply a reader who is looking for Ovid’s storytelling, then you will be just fine with letting the translator turn the ambiguity into something that makes sense (culturally and linguistically) in English. Sometimes the actual words don’t relate the actual meaning.

Ovid is lucky, in that he really does survive translation well. He can be reworked without losing his essential Ovid-ness. And it is true that some writers survive the tidal pull of translation better than others. That pull can distort some works beyond help, while others keep their gussets unruffled. Hence, a good translation of the Iliad or Shakespeare can work just fine in a new language, because the story is paramount. Shakespeare tends to travel well. His plays are valued in many lands and many languages. There are famous examples of Macbeth in Swahili, of Hamlet in Russian, and dozens of operatic versions in Italian, French and German. They all pack a wallop. And Shakespeare is loved in all those languages by their native speakers.

But that other class of writing, where the effect depends on how it is being said can defy the best translator. I have never found a good translation of Goethe, for instance. In English, his poetry often sounds commonplace. But I am assured by a native German speaker that Goethe’s poetry is the best from his country by being written in the most elegant of German language. Horace in Latin is similar; in English you wonder what the fuss is all about; in Latin, it is the height of sophistication and elegance.

Going in the other direction, how in hell can you translate John Milton into French? You can tell the story of Paradise Lost, sure, but how can you convey the special organ-tone quality of his language.

“Round he throws his baleful eyes.”

Translate it into French and it comes out as the equivalent of: “He looks around him malevolently.” Not the same thing, all the poetry is gone out of it. These things are untranslatable, and hence, Milton can never have the global currency of Shakespeare.

There is behind language, a world. You can concentrate on the language, or on the world. It is easy to be lulled into forgetting the difference, to think that words describe the world, and that the best language is the most accurate lens on the things of this world but they are not the same, but rather, parallel universes, and what works in words does not necessarily explain how the world functions. In the reality of our experience, there are no nouns, no participles. There is only “is.” Can you get at that “is” through words. We try. And we try again.

And so, Ovid is lucky, he takes translation with grace, even glee. For although his Latin is singled out as impeccable, it is the stories that matter, and we can get them in English (or French or German or Chinese).

Which is why my favorite version is Ted Hughes’ Tales from Ovid, which is only a partial translation (it includes just 23 of the hundreds of stories Ovid retells) and is really more a metamorphosis of Ovid into English: rewritten as if Hughes himself were telling the stories, rather than translating the words of Ovid. It is a re-creation rather than a translation.

It is a version I recommend to everyone as a complete joy.

Click on any image to enlarge