He stand up on stage, his back to the audience, raises his arms, flicks a thin shaft of wood and the orchestra sounds. As he beats time, the musicians keep up. He slows his arms, they slow the music; he speeds up, they race forward.

What is the magic of a symphony conductor?

The single most-often asked question I got as a classical music critic by a non-musician is: Just what does a conductor do? Is he necessary? Could I do it?

And this is a difficult question to answer, because orchestras differ, conductors differ and the music they play varies. No single answer is quite right.

For instance, when a Leonard Bernstein stands up in front of the venerable Vienna Philharmonic and gives a tiny wiggle of his wrist, the music stirs, just as if the baton were a swizzle stick; if a journeyman conductor stands in front of, say, an orchestra in Muncie, Indiana, and waves his arms like a madman, the players likely puzzle what the dickens he is trying to accomplish, or worse, are forced to ignore him.

(Or her — there are finally a growing number of women maestros, or maestras).

We say the conductor “leads” the orchestra, but what that means can vary quite a bit.

In current times, many conductors find themselves primarily in the position of traffic cops, keeping the music running on time, slowing the aggressiveness of the brass, or encouraging the timid violas to speak up.

In current times, many conductors find themselves primarily in the position of traffic cops, keeping the music running on time, slowing the aggressiveness of the brass, or encouraging the timid violas to speak up.

In past times, the podium-master was a magician, drawing from the orchestra a singular and personal reinterpretation of the score.

But, you say, aren’t the musicians professionals? Don’t they know how to play the music? And, of course, in a good orchestra, they are. If it is an “old hand” group, with a long history of playing together, the orchestra may decide they know better than the tyro conductor how that Mozart symphony should go, and then, no matter what the minimaestro signals from the stand, they ignore him and go their own way. This often improves the performance; old hands often DO know what they’re doing.

It also depends on whether the conductor is attempting a “standard model” performance, matching the so-called Platonic ideal performance that almost every classical music fan has in his head — in such cases, the orchestra can run on auto pilot quite well — or whether he is an idiosyncratic baton waver, who will be asking the musicians to rethink the warhorse, in which case, if they are a conscientious orchestra, they will attempt to follow the baton.

Some famous conductors were notorious for changing their interpretations during performance. Wilhelm Furtwangler, most notoriously, could ask them to do the opposite of what they had rehearsed. He often defended this by saying he doesn’t know what will happen in the hall, where acoustics can change with the audience, how full it is, or how much wool overcoat the crowd — and the reverberant sound — may be buried under. He also depended on momentary inspiration for his performances: This gave the Berlin Phil under his stick a presence and vitality rare in the industry: Every moment was alive with possibility, and never a routine run through.

Or Sir Thomas Beecham, who famously hated to rehearse, and would spend the time running quickly through each piece and then announce, “That sounds about right,” and then, during performance, ask them all kinds of somersaults and bounce from the podium.

Needless to say, not everyone can get an orchestra to turn on a dime, follow the baton like a setter on a leash, and roll over the interpretive cliff with the arch of an eyebrow. The major maestros can and could do this. The itinerant guest conductor is not often in that league (make that “almost never” and then cross out the “almost”).

There are those who decry an overly demonstrative baton-waver (Bernstein used to alarm an army of critics, who found him frantic on the podium, only later to change their initial opinions of him when they discovered he could draw life-altering performances from his charges). And there are those who praise the Laconian reserve of others, believing that there is some virtue in not hamming it up.

The truth is, either approach can create great music.

A symphony conductor has several jobs, not all apparent to the audience.

Let’s take them one at a time.

First, the major part of his work is done in rehearsal, not in performance. While working with the musicians, the conductor lays down the outlines of what he wants in the performance, things such as how fast they should play, how loud, and when the oboe should play louder to be heard over the horns, and when the horns should tone it down, so the oboe can be heard.

They work over phrasings, over such arcane things as the bowings to be used by the string players, the amount of vibrato, or when to alter the scorings (there are times when the parts must be gently rewritten for better effect — each conductor has his own conscience on such matters, but even the score-fanatic Arturo Toscanini regularly touched up his Beethoven).

They also decide when to take marked repeats and when to ignore them. (Failure to make such things clear can create disaster, as when Beethoven screwed up a repeat during the premiere of his Choral Fantasy and had to stop the music altogether and restart the band.)

They also decide when to take marked repeats and when to ignore them. (Failure to make such things clear can create disaster, as when Beethoven screwed up a repeat during the premiere of his Choral Fantasy and had to stop the music altogether and restart the band.)

In rehearsal, the conductor’s personality and approach can make a difference. In the past, some conductors were absolute dictators, brooking no backtalk from the galley slaves. Others were more collegial, asking in conversation with the musicians what might work best. (Sometimes the orchestra, for instance, knowing the hall better than the visiting conductor, can help him understand the idiosyncrasies of the performance space).

Nowadays, dictators are rare. Musicians unions and simple common-sense have toned town the tyrants. A conductor cannot easily get away treating his subordinates like dogs. This is better for the poor musicians, but not always better for the music.

Second, during the actual performance, the conductor tries to keep the music running on the schedule he has set during rehearsals, and tries to keep the musicians from straying too far from the plan. He beats time with his baton and uses his free hand to give hints, such as “more vibrato, please,” or “you, up there with the trombones, a little humility, please, we’re trying to listen to the cellos.”

But there is a third job the conductor has, and it is sometimes overlooked, indeed, oftentimes derided. That is the conductor’s duty to the audience. And I mean his visual duty, not merely his sonic one.

That is, the conductor, who knows the music well, can help the unsuspecting public understand what is going on in the music. Regular concertgoers don’t need much help with Beethoven’s Fifth, but especially in less familiar music, the body language of the conductor can point the listener in the right direction. The motions of the conductor can be theatrical for the audience, not merely technical for the players.

Certainly, there is a level of puritanism rampant in the classical music world that frowns on conductorial theatrics with the same disapproving hauteur that it reserves for those neophytes who applaud between movements, or leave the hall before the encores in what is sometimes called a “standing evacuation.” But a certain amount of theater can be a great help for the audience, who are often in the process of falling into a “confused slumber” while the music is droning on, and they can wake up for those moments when the conductor is hovering mid-air like an apache helicopter.

The magic a great conductor can create is one of those things, like charisma, that we have all experienced but can never explain. Some got it, some don’t. The pretenders are embarrassing.

There are fashions in classical music, just as there are with everything else. Currently, there is a widespread prejudice that a good conductor shouldn’t “interpret” the music, but should let the music speak for itself. This sounds nice, but it is rather like telling an actor playing Hamlet, just speak the words clearly, don’t “interpret” them. There is a reverence for the score that would do a hardshell Baptist proud speaking about holy writ.

Yet, some of the greatest recordings to come down to us demonstrate that the personal vision of the conductor can make the music, not only come alive, but provide for the audience such a profound and moving experience that they are willing to shell out the price, often dear, of a ticket for the next concert, in hopes of something equally thrilling, even life-changing.

And anyone who actually looks at a score will know, there are hundreds of details that need interpreting. A score is by necessity a rather vague document. It tells us the notes, but not the music.

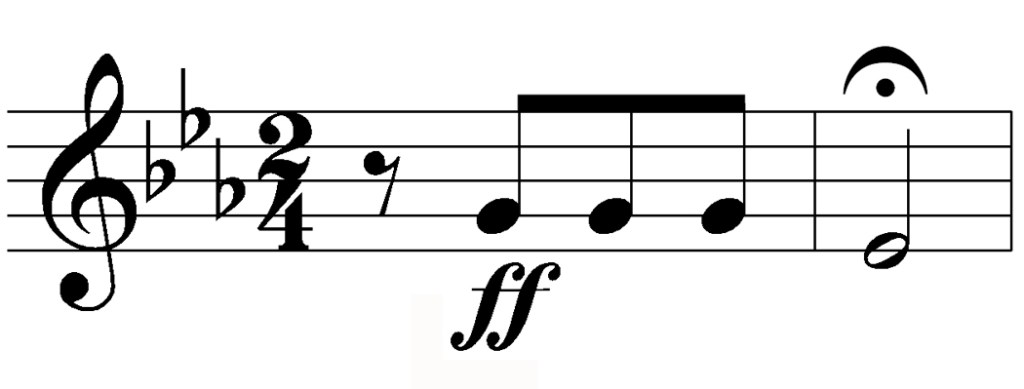

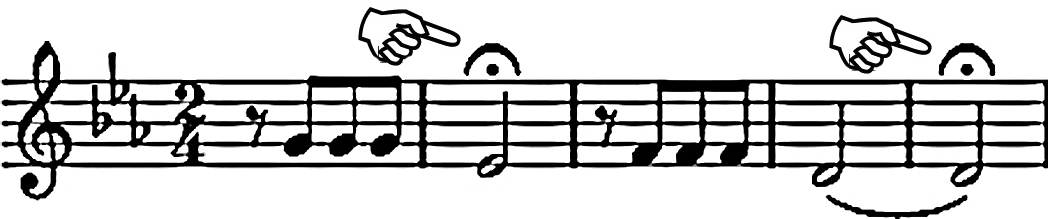

Click to enlarge

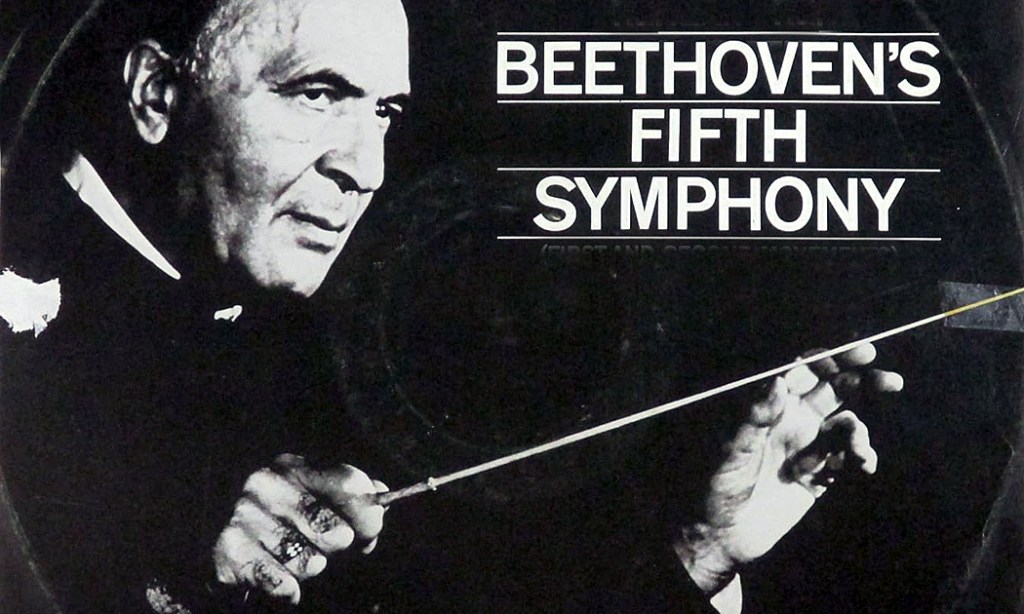

Let us take a well-known example: the first page and a half of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. We can point out a few of the puzzles a conductor must deal with. Sure, he can rely on his memory of a thousand other performances, but a conductor should always start with the score, and this one has lots and lots of questions for him.

Right from the get-go, there are those four opening notes: “Dah-dah-dah-Dum.” Then repeated a step lower.

They are usually played as a triplet and a downbeat: “ONE-2-3-ONE.” But notice that the score actually begins with a rest. This is in 2/4 time and there are four eighth-note beats before the bar line. It is “(rest) 1-2-3-ONE.” Which throws the rhythm slightly off and turns it from a triplet to a pair of iambs. The first and third beats of a bar are accented; the second and fourth are recessive. The first note is on the second beat, so, the first bars go like: “I CAME to PLAY; I’m HERE to STAY.”

OK, but that creates a problem. As the symphony progresses, we hear that four note motif hundreds of times, and often so fast, piled one on the other that keeping the fine point of the rhythm is very difficult, especially for lesser orchestras. And when we hear it so often as a pattern, we tend to hear it as a triplet and downbeat.

Further, if we look deeper into the symphony, we find that the four note motif is repeated in all four movements, and in the third, it comes in a triple meter: It actually becomes ONE-2-3-ONE.

So, perhaps Beethoven always intended it to sound like three-and-one. Here is a decision that has to be made in rehearsal: The orchestra has to all agree, or at least the conductor has to decide which way he’s going to play it.

You can hear different recordings of the symphony and in some, you can hear the triplet-and-downbeat and in others you hear the pair of iambs.

The next decision you have to make concerns those two prominent fermatas (the “eyebrows”) over the second bar and the fifth bar.

They indicate Beethoven want you to lengthen those notes and hold them longer than their measured length. But how long should you hold them? This will depend on how you see the rest of the symphony, or at least the rest of the movement.

Look at the first page and a half and notice how often there are rests and fermatas. This is a very odd symphony. It begins with a lot of ambiguities. Not only the issue of triplet or iamb, but what key is the damn thing in? The first four pitches are G to E-flat and F to D. There is no bass note to tell us whether we are in the key of E-flat major or in C-minor. It could be either. And with all those pauses and fermatas, we can’t initially tell whether the movement will be fast or slow.

As Professor Peter Schickele says in his sportscast of the Fifth Symphony, “I can’t tell if it’s fast or slow, because it keeps stopping.”

This brings up a major interpretive choice the conductor has to make. Should he try to smooth things out to make a continuous movement with a propulsive sense of drive, or should he emphasize the herky-jerky stop and go? After all, Beethoven intentionally put all those stop signs along the road.

You can get an immediate idea of what your conductor thinks with how he handles those two first fermatas.

If he wants to drive the thing forward, he will barely hold the E-flat and D under the eyebrows, and keep the rhythm as propulsive as possible. Otherwise, he may tend to hold those notes a very, very long time, breaking up any sense of forward motion.

Listen to two extremes: First, conductor Benjamin Zander, with a student orchestra plays the first movement like a bat out of hell, running through the stop signs. It is exciting and propulsive. It’s hard not to be caught up in the excitement.

Listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4gXdWELSgEQ

Then, listen to Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Berlin Philharmonic in 1947, in the first performance the conductor was allowed to lead, after being finally cleared of Nazi leanings. The emotions, not just the thrill, are deep and profound. The world has just survived the worst war in history and the man who loved music and Beethoven above all else is finally allowed back with his beloved musicians. What a deeply moving performance, but how utterly different from Zander’s.

Then, listen to Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Berlin Philharmonic in 1947, in the first performance the conductor was allowed to lead, after being finally cleared of Nazi leanings. The emotions, not just the thrill, are deep and profound. The world has just survived the worst war in history and the man who loved music and Beethoven above all else is finally allowed back with his beloved musicians. What a deeply moving performance, but how utterly different from Zander’s.

Listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2qMwGeb6SfY

Some will say that it is Furtwangler’s emotions we are hearing, not Beethoven’s, but perhaps they need to be reminded that what we’re really talking about is emotions we all share. The audience had just been through a great conflagration. Their nerves were shot, emotions were near the surface. The performance acknowledges that: It is music for the NOW of the moment, and not a recreation of some 19th century moment. Surely this is the true purpose of the concert. If Furtwangler makes the undercurrent all the more palpable, he is truly giving us the heart of the music.

This may seem like a lot of fuss to be made over four lousy bars of music, but they are essential to understand the music.

Now, if you look at the succeeding bars, you will see that the four-note motif gets tossed around the string section, from second violin to viola to first violin, and then repeats, as if it is piling the motif up on itself.

Taking approach No. 1, you want the motif to build into a theme, and you want the pattern to play as if it were performed by a single instrument, in a single singing line. If you take approach No. 2, you want to phrase the thing so that there is just a little hitch between violin 2, viola, and violin 1, so they can be heard as separate voices.

That phrase repeats, and then the four-note motif goes through its first metamorphosis, and becomes not three repeated notes, but in the treble, two repeated notes, and descending eighth note and then the downbeat note. It is a slide downhill. It is answered by the bass notes doing two repeats and a rising eighth note before the downbeat. Going uphill.  Approach No. 1 is to play these patterns almost as a sine-wave down-up, down-up, again as if it were a single singing voice. Approach No. 2 plays treble against bass, as if they were arguing, “I’m going downhill!” “NO! I want to go UP!” Back and forth.

Approach No. 1 is to play these patterns almost as a sine-wave down-up, down-up, again as if it were a single singing voice. Approach No. 2 plays treble against bass, as if they were arguing, “I’m going downhill!” “NO! I want to go UP!” Back and forth.

Again, you accomplish this by phrasing the notes with a little hitch between the parts. That hitch is too short to be notated, and in fact, doesn’t necessarily alter the beat at all, but rather you simply hesitate a microsecond before each entry, creating a minuscule gap between the phraselets. Disintegration, not the through-line, is the guiding metaphor for this version of a performance.

You might notice in the score that underlying this sine-wave/argument the cellos and bassoons are playing an alternating C and B, which are the home note and leading tone of the key of C-minor. The conductor has to decide how prominent to make this counter-melody. Is it merely background, or is it something paying auditory attention to?

You might also notice that until this point, the double bass has had nothing to play, outside underlining the opening motif notes. Since then, they have been silent. But now, the whole orchestra lights up in a tutti cadence, and we come to a natural “joint” in the structure of the symphony, a big gesture rounding off a section of the musical argument. (You don’t need to understand this, but the cadence uses a D-major chord, technically the dominant of the dominant, to end the cadence on a G-major chord, the dominant chord of C-minor — for the first time, Beethoven has used a chord outside the key of the symphony).

But wait, as Ron Popeil might say. That cadential G-major chord includes a whole note with fermata on the first violin section, which seems to have taken it upon itself to play “outside the box,” as it were, refusing to punch out that G-major with the same brusk hit that the rest of the orchestra uses, it holds on, as if it were a misbehaving child.

Again: How long should the violins hold that fermata? Approach No. 1 says, not long, we don’t want to slow things down. Approach No. 2 says “But we’re trying to interrupt the flow as often as we can.”

While we are on that half-note G that the violins hold, a decision has to be made whether the note should be played at a constant dynamic level, and a constant intensity, or whether it should include a bit of a climax: Should they slightly increase the volume as they hold the note, or slide the bow lower on the string to change the intensity and timbre of the tone as they hold it; should they do a slight decrescendo on that note, letting it die away; should they do a slight increase and then decrease in volume or intensity, making a kind of whoooOOOOooo out of the note; and should they just end the note, or let it die away, or should they punctuate the end with a kind of plosive end, as if they ended in a “T” or “P” sound? The choice will depend on what the conductor believes the symphony is trying to accomplish.

So, with that fermata, does the conductor hold up the next series of notes a bit, or does he dive ahead as strictly as he can? Of course, the next notes are the four-note motif again, and another fermata and another stutter and hold.

One thing I haven’t mentioned yet is the basic tempo. Beethoven gives us a metronome marking for the movement, where a half-note beat registers 108 on the Maelzel metronome. This is very fast, indeed. There is a problem — or at least a question — about Beethoven’s metronome markings. They are all rather fast, compared to the way the symphonies have been traditionally performed. The HIPP (“historically informed performance practice”) crowd believes the metronome markings should be taken seriously and biblically. The traditional crowd notes that Beethoven didn’t come up with these metronome markings until late in his career — they are retrofit to the scores — and that when he came up with them, he was stone deaf. They point out that the early metronome Beethoven had may have been malfunctioning. And that if you hear music only in your head, it is likely to be heard faster than you would experience it in a working ear.

When he actually tried to perform the allegro of his Ninth Symphony at the tempo marking he originally indicated, he realized it was off by a third, and reduced it from a metronome marking of 120 to 88. We should keep that in mind when we proscribe any variations from the printed metronome numbers.

Either way, Beethoven made clear that he wanted the tempo indicated to refer to the beginning tempo only, and that he expected his musicians to alter the tempo as the music progressed to further its expressivity.

The quote: “My tempo markings are valid only for the first bars, as feeling and expression must have their own tempi,” he wrote.

Beethoven was no fan of metronomic performance.

And, how can you have a meaningful metronome marking when the music keeps stopping and notes are asked to be held against the prevailing metronome beat?

A lot of decision have to be made even in this first page and a half. Many of them have to be hashed out in rehearsal, so the orchestra is on the same page with the conductor.

But others can change during performance.

The phrasing has to be agreed on before the performance, but things like how long to hold the fermatas may change during performance depending on many factors.

You know in theater, how the audience can affect the actors’ performance. A good audience brings out a better performance; a bad audience can turn the actors into automatons or can make them exaggerate their performances to try to force a reaction from a recalcitrant audience.

The same in music, and the conductor may alter his tempo, the length of holds and rests, in order to underline some interpretive detail that he believes the audience is not paying attention to, or conversely, is so in tune with the music, that he can risk some interpretive byways he would not attempt with a less attentive group.

Or, it could be the occasion: Some national figure has just been assassinated, or some city has been bombed: the ritual significance of the music may make for a deliberately more emotional performance.

Furtwangler recorded the Fifth at least 12 times over the course of his career, from 1926 to 1954, and anyone who cares about the music deeply wants to have as many as possible, because they are each different. There’s one from before the war, during the war, the one just after the war when the conductor was first freed to perform again, and then recordings from the 1950s, in better sound, but as the conductor was aging. In 1943 in Berlin, the war was in everyones’ hearts and minds, and Furtwangler brings greater intensity to the music, with longer fermatas and more intense phrasing. Other recordings he made at different times are quite different. The particular way he plays the music was most likely spur of the moment, created during performance and not in rehearsal, as he asked the orchestra to “feel” along with him what he was attempting to do.

I hope I haven’t bored you with too much detail, or patronized you by saying things you already know quite well. I just want to help you enjoy classical music as much as I do. I cannot imagine life without it: As Nietzsche said, “Life without music would be a mistake.”