In addition to this blog, which I have been writing since 2012, I have written a monthly essay for the Spirit of the Senses salon group in Phoenix, Ariz., since 2015. I was, at various times, a presenter for the salon, which arranges six to 10 or so lectures or performances each month for its subscribers. Among the other presenters are authors, Nobel Prize-winning scientists, musicians, lawyers and businessmen, each with a topic of interest to those with curious minds. I recently felt that perhaps some of those essays might find a wider audience if I republished them on my own blog. Here is one, from July 2, 2016 slightly updated and rewritten.

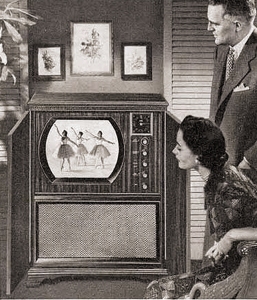

It is said we are in a golden age of television. Not so much because of what is available on broadcast TV, but what is available on cable and on live streaming video, such as Netflix and Hulu.

It’s hard to argue against this, what with so much out there to see, from Game of Thrones (at perhaps one extreme) and Book TV on C-Span (at the other end). For many, this new Golden Age was born with HBO’s series, The Sopranos. It certainly made a quantum leap in what was possible on the tube.

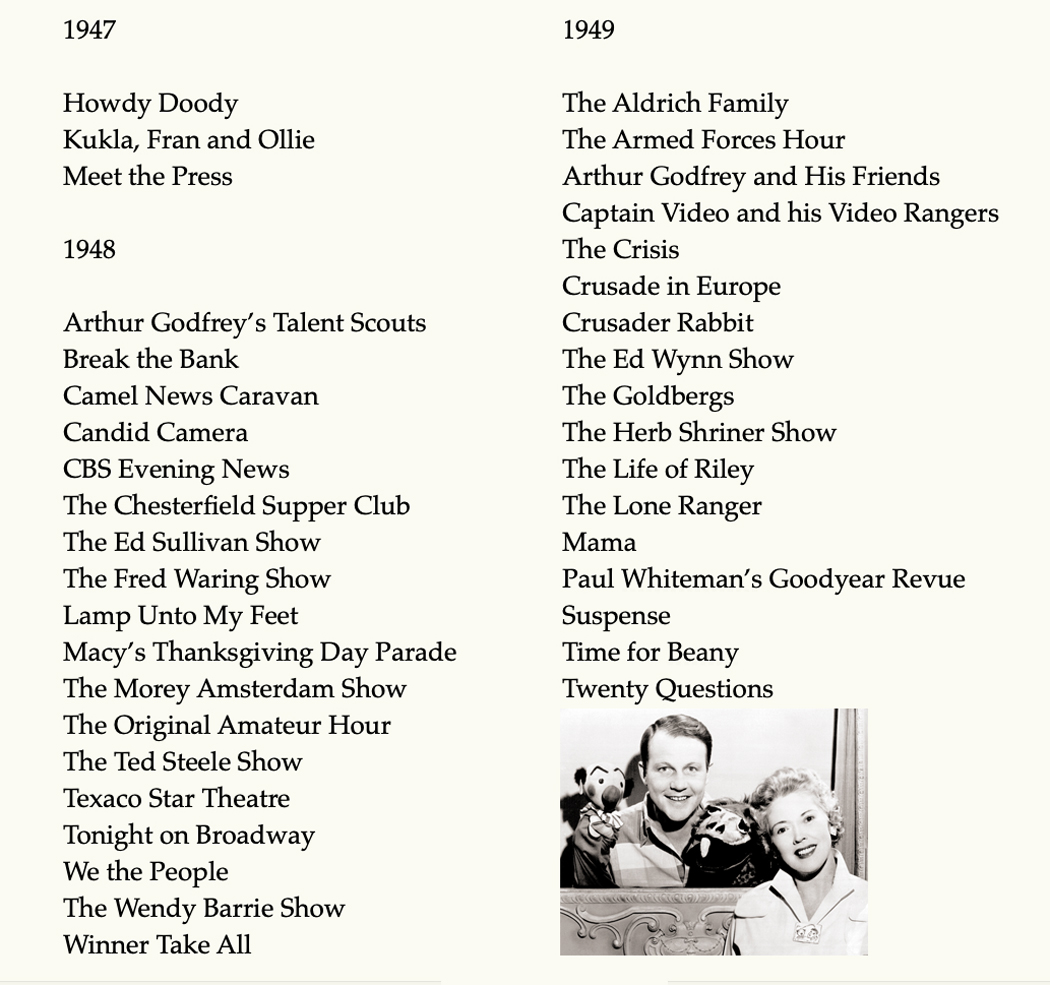

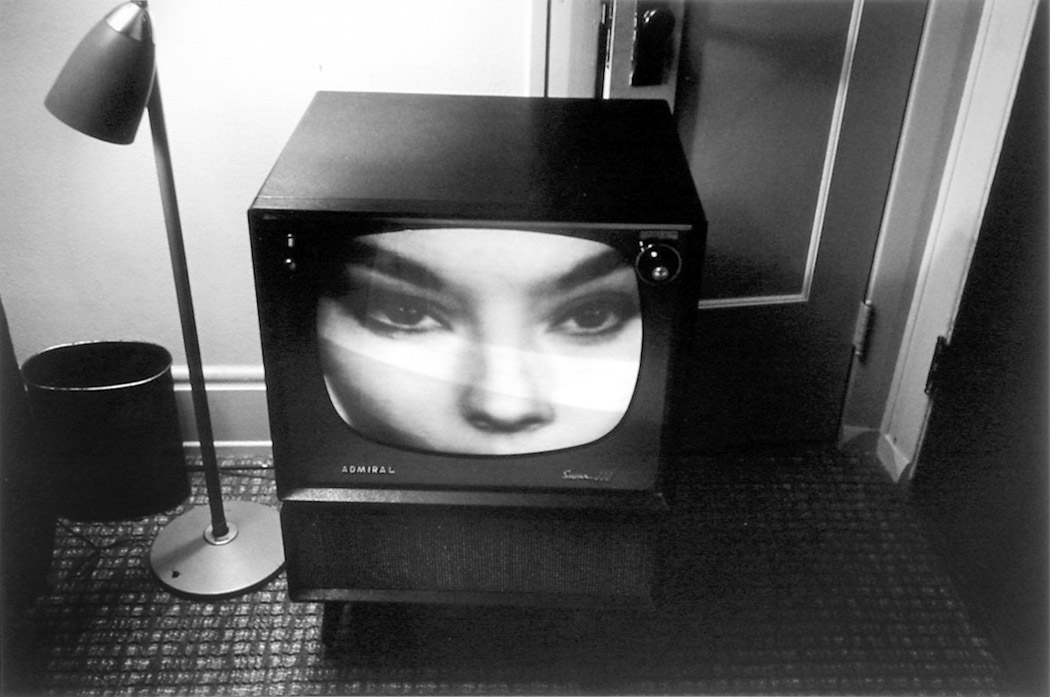

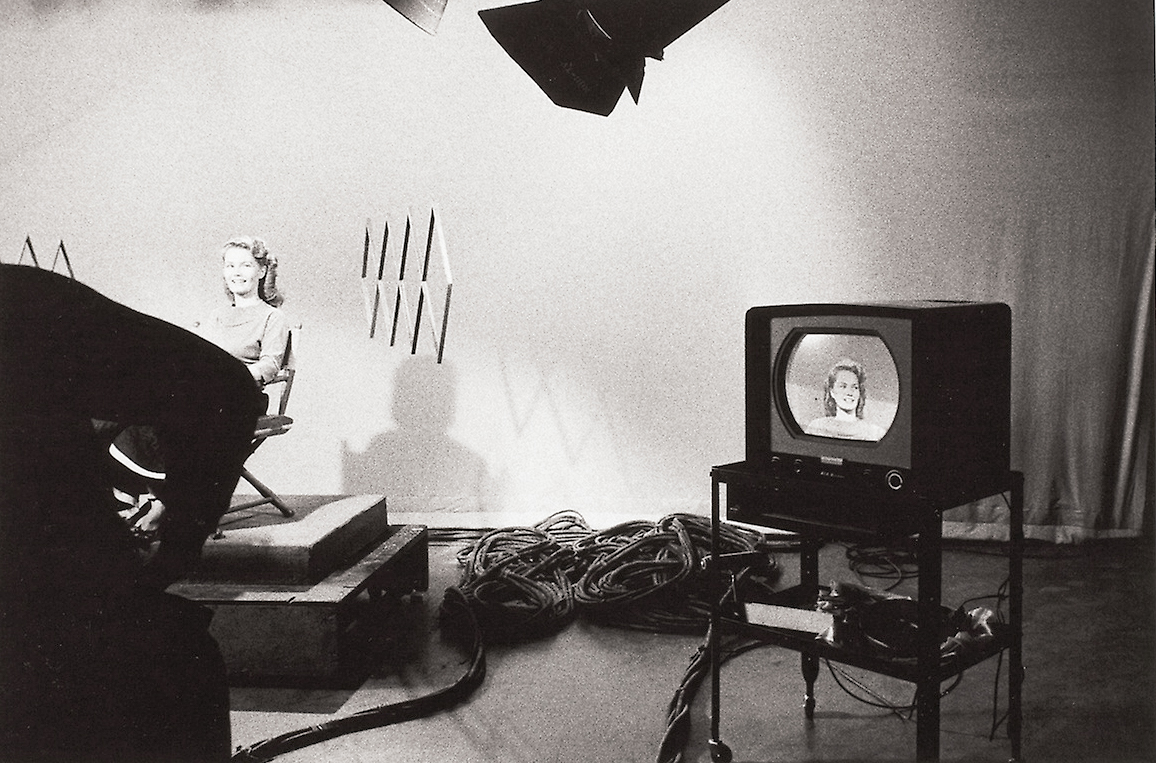

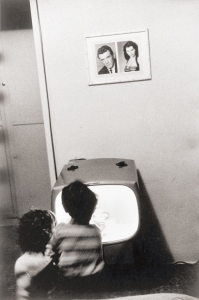

But, for an entire demographic segment, the term “Golden Age” is reserved for another time, another place. I grew up in the first Golden Age of Television, its earliest years just after the Second World War, making TV, just as much as myself, a baby boomer. There is little left of that first Golden Age that isn’t merely the buzzing of neurons in the memory of an aging generation. What survives beyond that are some gray, blurry kinescopes and whatever was shot on filmstock in those nascent years. Even that is hard to come by, outside a few remnants retrievable on You Tube.

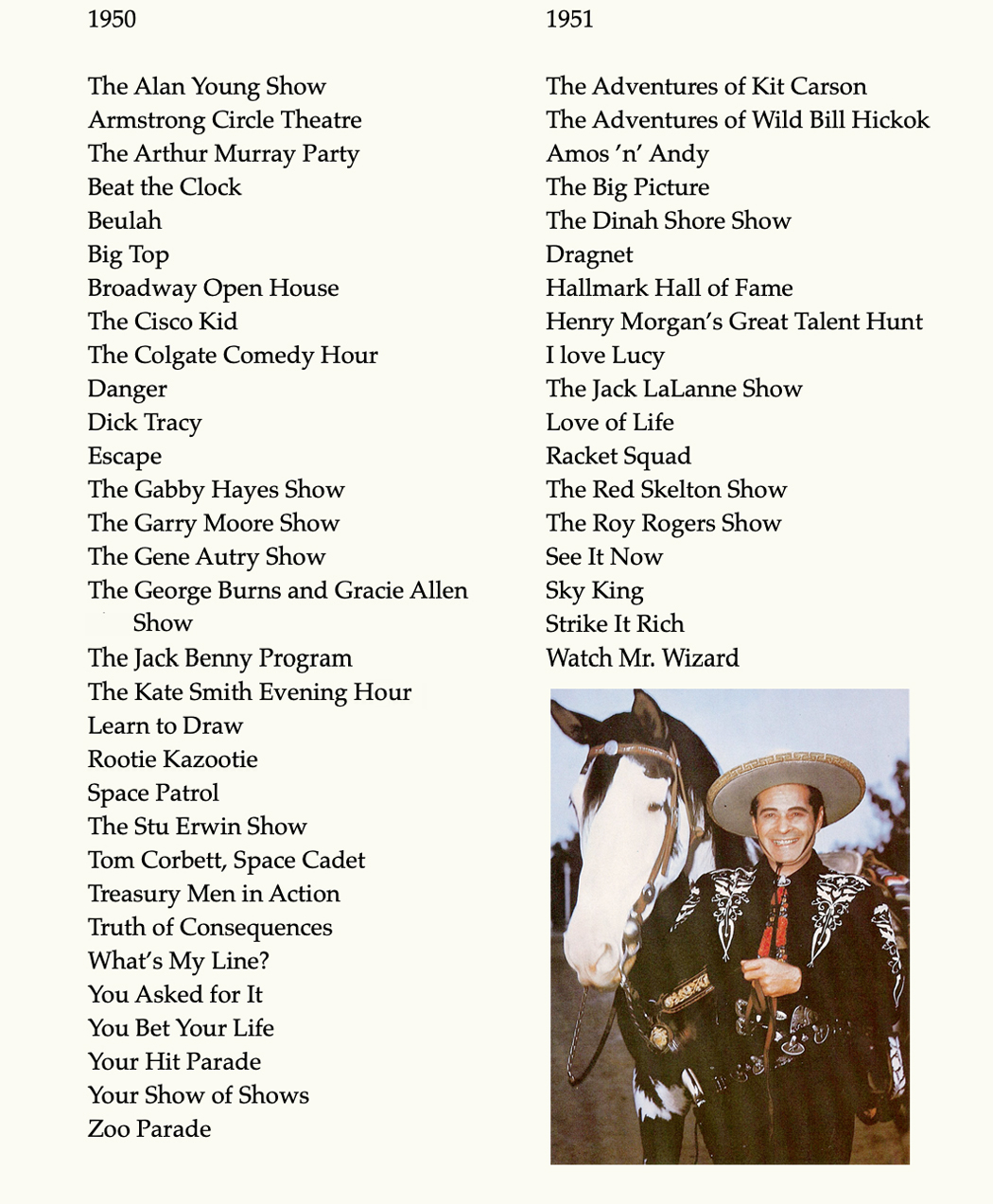

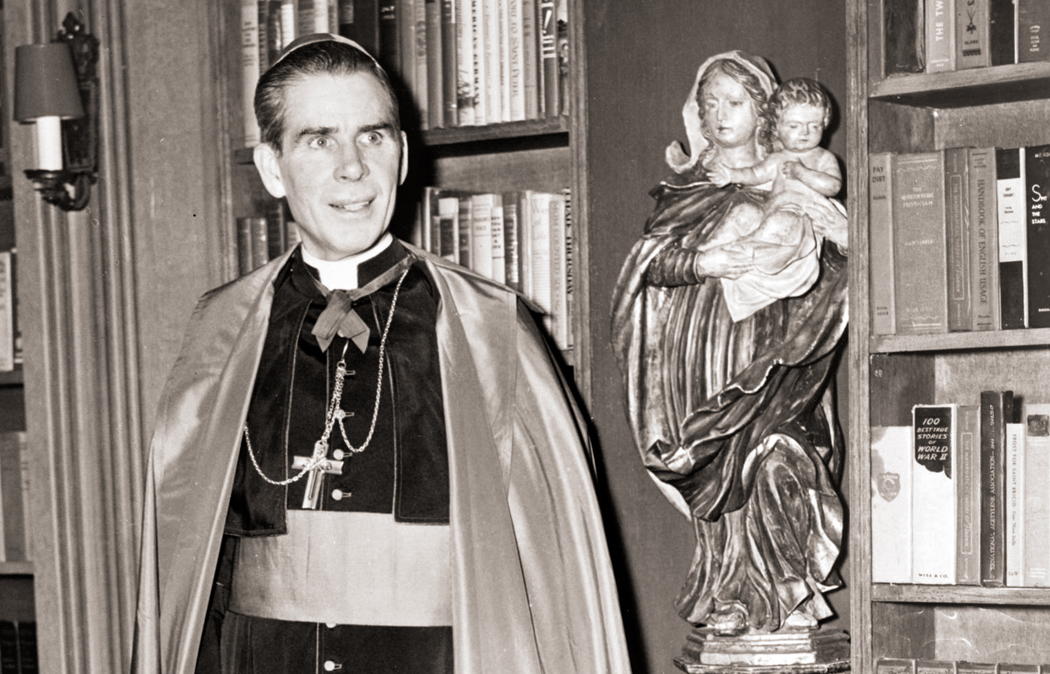

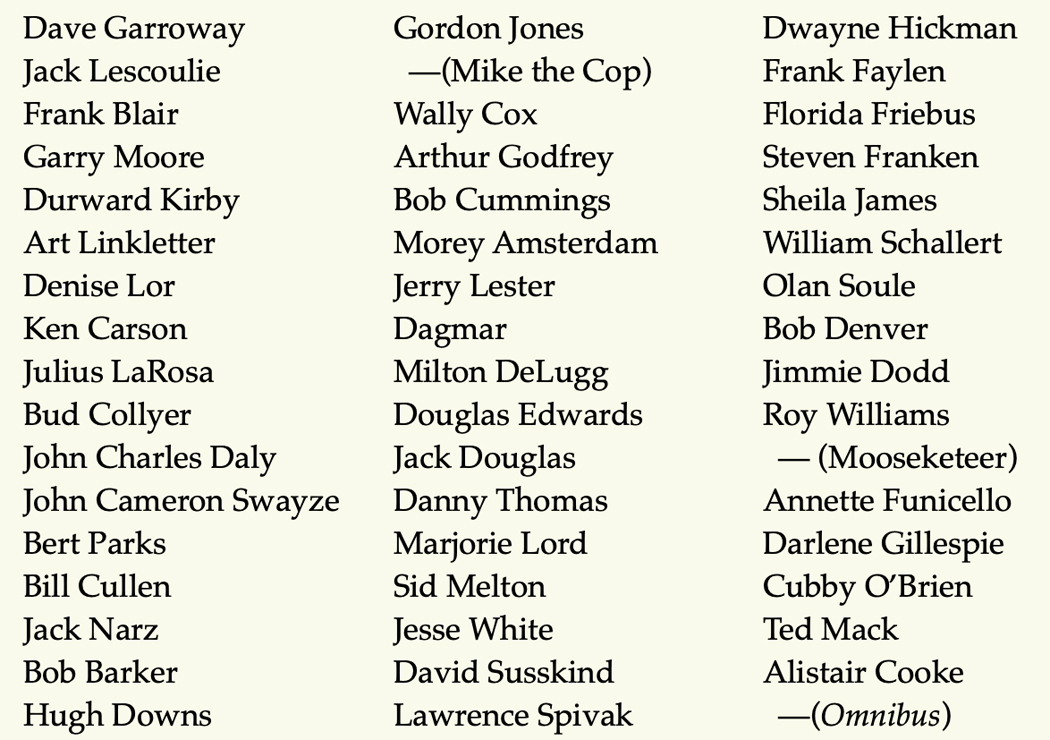

What was special about the first decade of broadcast, despite the technical and budgetary limitations, was the sense that anything was possible. Since it hadn’t existed before, no one knew exactly what TV should be, and so, they threw everything up against the wall to see what would stick. And the current generation would be astonished at what became popular, like Bishop Fulton J. Sheen in his purple vestments talking to us in his calming but authoritative Catholic voice on Life is Worth Living, or artist Jon Gnagy giving lessons on How to Draw, or Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony from 1948 to 1952.

Their modern counterparts now find their home on obscure cable channels or PBS, but Bishop Sheen was on the Dumont Network and then ABC. Gnagy was originally on NBC. In its earliest years, television was willing to try anything. There were home travelogue movies on Bold Journey and I Search for Adventure (with Col. John D. Craig); there were African adventure series, Ramar of the Jungle and Jungle Jim; there were cop shows such as Highway Patrol and Racket Squad (it is surprising how many of these shows come in competing pairs); Captain Video and Captain Midnight; Mama and The Goldbergs; Ozzie and Harriet and George Burns and Gracie Allen.

The last of these was surprisingly ante-post-modern, as George Burns would watch his own TV show to discover what was happening in the episode he was in. More than breaking the fourth wall, it was breaking the fifth.

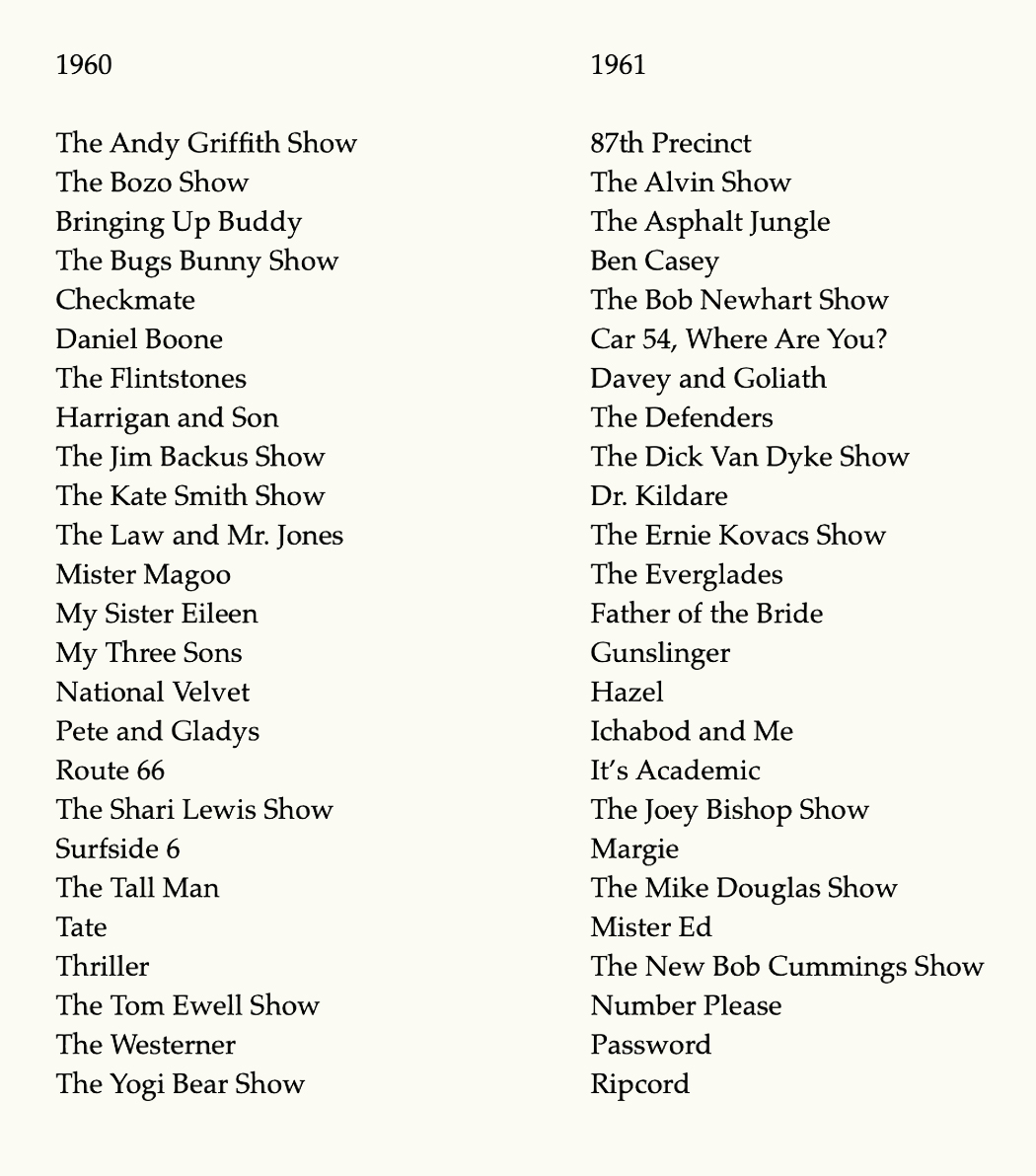

By the end of the 1950s, television had begun to feel like the familiar boob-tube we all know and love. The programs were becoming settled and familiar. There were Westerns, cops shows, talk shows, game shows — all the usual furniture of the air waves.

But when I was a wee bairn, it was all a bit wild and wooly. Because there wasn’t enough content available to fill all the time, television went blank in the middle of the night and didn’t light up again till well into the next morning. And because there was a shortage of content, a good deal of the detritus of Hollywood was repurposed for the tube, which means that I received a graduate-level exposure to the B-Westerns of the 1930s. I knew well such stars as Hoot Gibson, Tim McCoy, Bob Steele, Buck Jones and Johnny Mack Brown. I still know the difference between Fuzzy Knight and Fuzzy St. John.

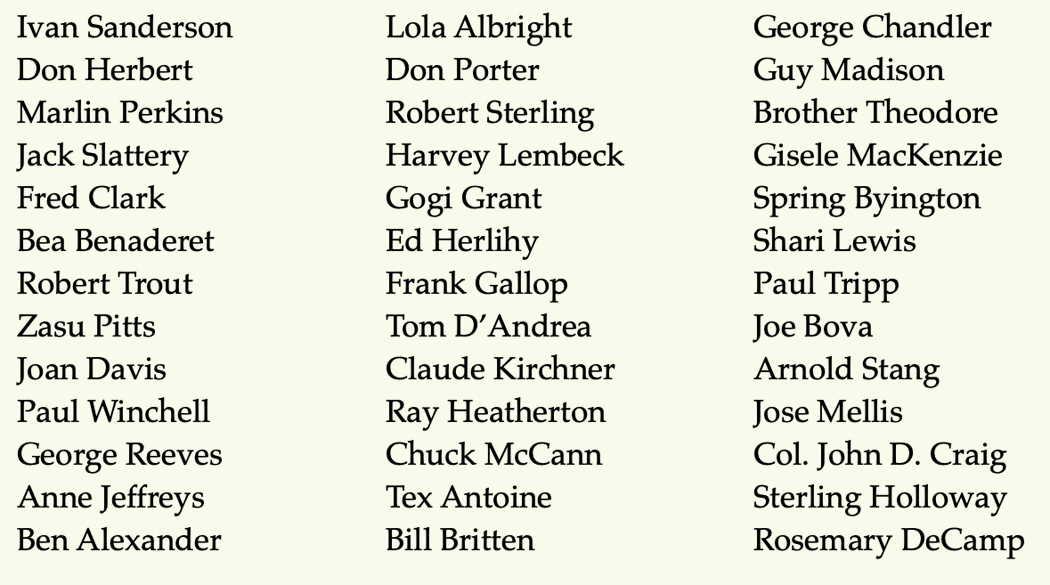

Some of the old actors found new work on the small screen. Western sidekick Andy Devine first worked as sidekick to Guy Madison in the Wild Bill Hickock series of half-hour oaters, but more memorably, as the host of Andy’s Gang, a children’s show featuring a serial of Gunga, the East Indian Boy, and a retinue of animal and puppet regulars, including Froggy the Gremlin, a classic trickster, and a phrase that re-emerged during the drug-hazed hippie era: “Pluck your magic twanger, Froggy!”

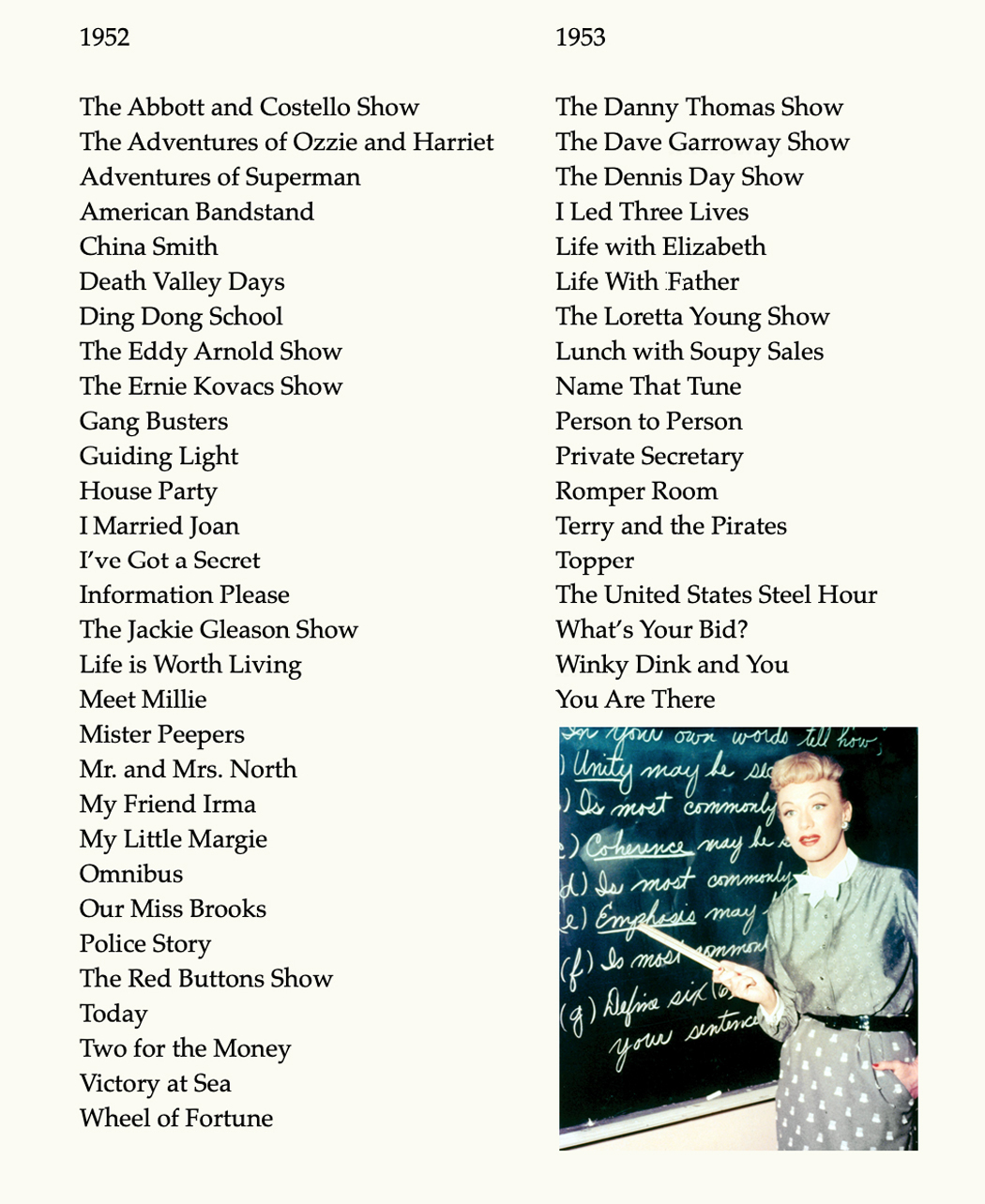

It would be easy — and tempting — to recall all that rubble that has collected in the mystic chords of memory from a childhood ill-spent in front of a glowing cathode-ray tube, but what I really mean to say is that what enters the consciousness at that tender age remains a touchstone for the rest of our lives. If our everyday childhood was one of front stoops and schoolyards, of family supper and the pinch of a new pair of shoes, what we watched through the glass bubble was the big world, the larger world that we knew we would eventually grow up to inhabit, and it was a world more interesting, more important, more everything than the ordinary one we woke up to each day, and that gave us a sense of the world that colored the rest of our lives. The actual matter of television was indeed a “vast wasteland,” but that hardly mattered. It seemed like magic to a six-year-old watching Art Linkletter in the afternoon or Abbott and Costello before dinner.

I know, for a generation earlier than mine, the same transcendent glow attached to radio — “Only the Shadow knows” — and that same sense of magic is what Woody Allen’s movie Radio Days is all about. But for anyone born after the war, it was television.

I am reminded of this by my youngers, who apparently feel the same “Golden Age” glow about their TV shows. How can one wax nostalgic about Gilligan’s Island or The Brady Bunch? They were such godawful shows. Or Scooby-Doo? Not my circus, not my monkeys. They are a grey cloud of mediocrity, but nevertheless the glowing childhood of those who came after me. Surely that is what any Golden Age is. Somewhere there is a class of novice businessmen whose sense of the world’s magic glow was a result of an infusion of Teletubbies.

When we are children — and I mean from the first memories until maybe second grade — everything is new, and because of that, it is radiant. It glows from inside and is what we aspire to throughout our lives, even when we go through divorces, failures, traffic tickets or bad clams. There is something ignited in us at that early time that is somehow a pilot light that remains. When we talk about a Golden Age of television — whichever age it is for us — it is primarily that inner light that we call gold.

And so, it feels quite different when we talk about the current era as being the second Golden Age of television. TV, like us, has grown up, and the current crop of shows that garner critical acclaim tend to be full of “adult” content, sex, drugs and vaulting ambition, violence and treachery. It speaks to us of a world very different, where orange is the new black, Kimmy Schmidt escapes from a doomsday cult, and the kingdom of Westeros is not so much dog-eat-dog, as dog-rapes-and-beheads-dog. It is a world very hard to explain to Mr. Peepers or Gale Storm.

The new Golden Age is infinitely more sophisticated and better written. It takes on the real issues of the world, albeit in metaphorical form, and gives us some real meat to chew on. I am not denigrating the new Golden Age. At its best, it is as real an art form as Greek tragedy.

But the earlier Golden Age, where “Uncle Fultie” left us rapt with homilies, and Morey Amsterdam played the cello and told jokes on morning TV, where Victory at Sea replayed the previous decade’s war with narrator Leonard Graves’ booming “voice of doom,” and Miss Frances taught us right from wrong on Ding Dong School, it has left a residue in my psyche — fuzzy as a kinescope — that has infected me with this damned unexpungeable sense that the world may be — despite House of Cards and Game of Thrones — somehow and inexplicably redeemable.