At the bottom of every product entry on the Amazon webpage you will find customer reviews. Some are quite thoughtful, others merely complain that the package they got was dented. Too often, close reading shows that the review shown is for some other product altogether and simply slung in with the rest by someone — or some algorithm — that wasn’t paying close attention.

Check out Google’s list of restaurants near you and you will find any number of reviews by those who have eaten there, and often with an iPhone photo of their dinner plate. These range from “The worst scungilli I’ve ever tasted” to “The cleanest restroom I’ve had to use.” Again, perhaps with a photo.

My favorites are those where someone posts a four-star CD review with the words, “I haven’t heard this yet.”

More than ever, we are led to believe that “everyone’s a critic.” Opinions are like noses (I’m being polite): Everyone’s got one. But I spent 30 years of my life as a professional art critic, and it has always bothered me that the wider public seems to think that real criticism, by people who are actually paid to think about such things, is little more than “I liked it,” or “I didn’t like it.”

On such a level, yes, everyone’s opinion is valid. If you liked it, then to say so is an obvious truth. But that is not what a professional critic is paid to do.

Granted, there are some people out there with the title on the masthead who do little more than report their likes and dislikes. But the kind of criticism I’m talking about — and that I did my best to engage in — has very little to do with simple likes and dislikes.

I was paid, rather, for my range of knowledge about the subject, about the history of it, the variety of it, the consensus about it, and my ability to say something meaningful and coherent — and interesting — about it.

I was paid to explain what I was seeing, put it in context, say why it is important — or not — and, especially with new art, to attempt to unknot difficulties that may make understanding elusive. The art world is full of “elusive.”

I began as a freelance art critic with the Virginian-Pilot in Norfolk, Va. in the mid-1980s, and became staff critic with The Arizona Republic in Phoenix, Ariz., in 1987, where I worked for 25 years until I retired in 2012. By then, newspapers were in decline and few still had any critics on staff as layoffs became as regular as seasons. When I left, I was not replaced. All across the nation, critics are not being replaced; lights are blinking out all over the heavens. The loss is considerable.

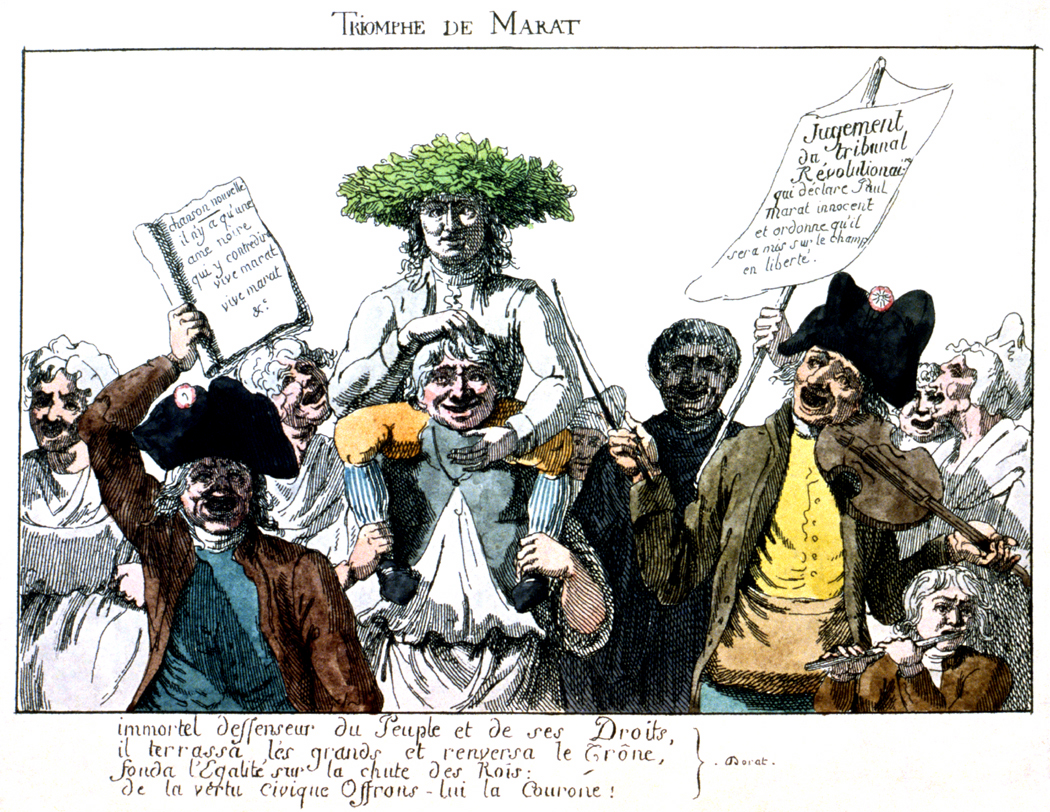

I have continued to post about art on this blog. There was a long piece about Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Marat. Another on the long echoes from the pose of Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus. I wrote about photographers Nan Goldin and Garry Winogrand. Some of these have been the most frequently visited blog entries on my site.

Over those three decades in journalism, I covered an awful lot of art, both locally and nationally. Much of the art, I loved. Some not so much, and there were even shows of art I had little sympathy for. All of it, I tried to say something real about and meaningful. So, I feel I have established my bona fides to write about criticism.

My tastes didn’t stop me from recognizing quality or importance, even if it was art I didn’t much care for. And there was, correspondingly, art I knew wasn’t especially important that I really, really enjoyed. My likes and dislikes didn’t count much, and weren’t supposed to.

Let me give you some examples either way.

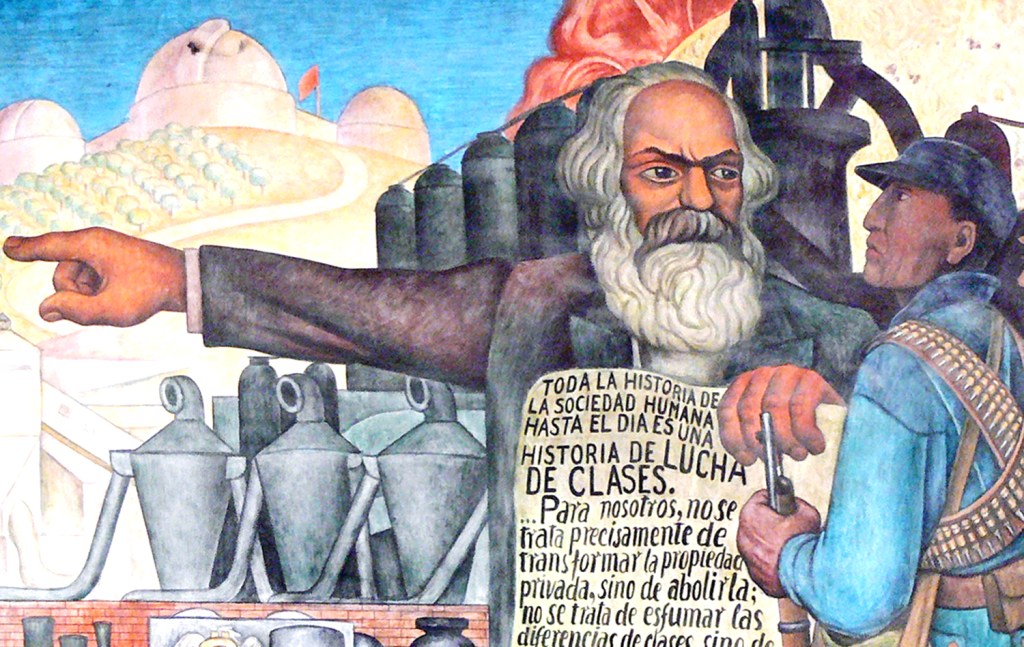

One of the very few times I had a contretemps with my editor was about a show at the Phoenix Art Museum of art by the so-called Mexican Muralists. I mentioned to my editor that I was thinking of giving the show a pass and she nearly bit my head off, making it absolutely clear that I wasn’t being paid not to write about an important show, or to care whether I liked the work. I knew this, of course, but I had to confess my lack of simpatico with the work. Of course, I wrote about it. Without expressing my own qualms.

In general, I have little love for art that is primarily propaganda, and that is just what the work of Diego Rivera or David Siqueiros is. There is good ol’ Karl Marx pointing the way to the future for the downtrodden campesinos. There are the peasants displaying solidarity by all wearing the exact same clothes and carrying the exact same weapons. For me, this is a big snooze.

And on top of that, the colors used favor rather dull browns and ochers. It just isn’t very inviting or attractive art. Nevertheless, the movement, from the 1920s through the 1940s, defines an era of Mexican culture, and was immensely important. And, moreover, some of the muralist art was clearly better than other, and it was my job to show that and explain why and how.

It should be pointed out that it isn’t Mexican art I have a problem with. I love the crazy work of Frida Kahlo; I wrote an appreciative review of Rufino Tamayo for ARTnews magazine. I enjoy the skeletons and calaveras of Jose Posada and the volcanic landscapes of Dr. Atl. And all that colonial-era art, and all the bright, colorful, energetic folk art.

It’s just the dreary, politically sentimentalized work of the muralists I dislike.

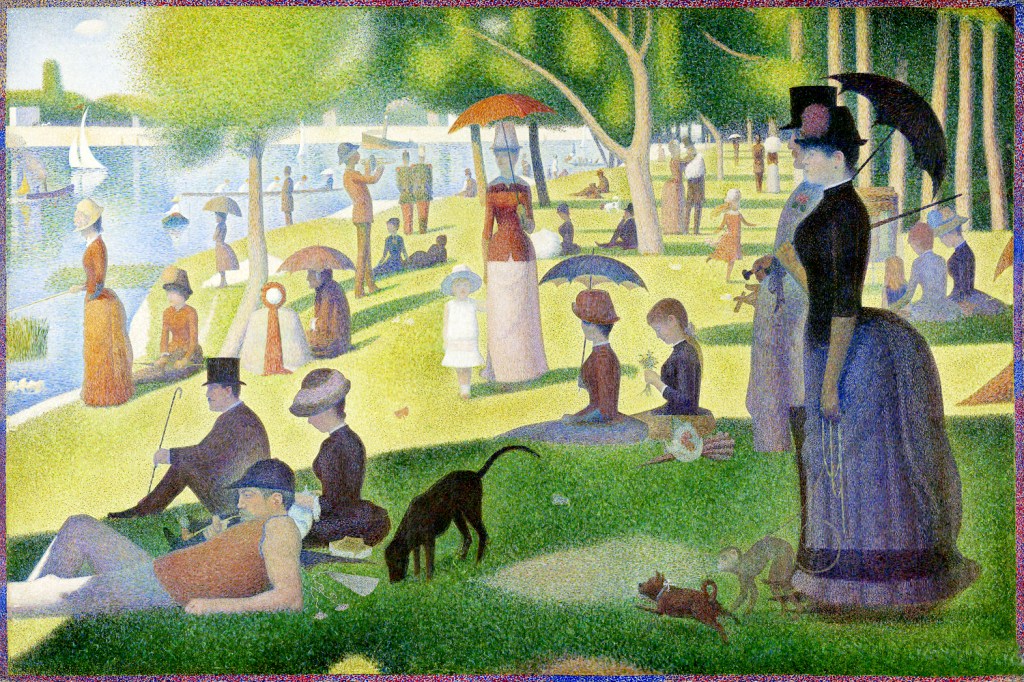

Let me give you some other examples. There is no question but that the pointillist works of Georges Seurat are masterpieces, and important in the history of art. But I find Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grandes Jattes a huge bore. Stiff and unyielding, all the life sucked out of what should be a bustling joy. It seems to me a painting made to justify a theory, and not something that had any more lively reason to burst out of his imagination.

And there is his older contemporary Camille Pissarro. I don’t dislike Pissarro’s painting, but it just seems a trifle dull. He is the painterly version of a composer who can write perfect fugues, knows voice-leading, and can orchestrate magnificently, and yet cannot write a tune I can whistle.

I’m specifically writing about art I have actually seen in person, and not just stuff I find in books or magazines. Reproduction cannot give anyone a clear idea of the art, its size, gloss, color. You can only get the iconography and some loose sense of everything else.

The necessity of seeing the art in person was brought home by Paul Cezanne. I never cared much for the work of Cezanne. But then, I spent some time with the actual work, and it exploded in my eye with form and color that just eludes reproduction. Now, Cezanne is one of my most loved artists and I kick myself for all those years when I paid him scarce attention. Those apples and pears — I want to lick the paint off the canvas.

Another confession: I never cared for Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. I’ve been to the Louvre now, several times, and in person, the Mona Lisa is no more exciting. It is a small, rather ordinary portrait. Yes, the sfumato technique is quite pretty, but the painting itself does not deserve the fame it seems to suffer.

On the other hand, I do love the same artist’s Ginevra de’ Benci, at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. It has all the glow and spirit that poor Mona Lisa just doesn’t have.

But even Ginevra doesn’t draw the pleasure from me that I get from Raphael’s portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, one of the most perfect paintings I have ever seen.

Rembrandt saw the portrait, copied it in pen and ink, and later used it as inspiration for one of his self-portraits, now at the National Gallery in Washington. I love that one, too.

So, it is not that I hate great paintings and love minor ones. It is just a matter of taste. My taste drifts toward some and is left unmoved by other. But, as a critic, I certainly know the difference.

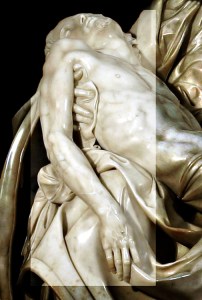

I have no issue with anyone liking or disliking any piece of art. Not everything has to appeal to everyone. If you think Damien Hirst’s pickled shark is disgusting, I have no issue with you. If you think the hands on Michelangelo’s David too large, and his privates too small, that’s fair. Even if you find yourself moved emotionally by the light inside the cottage of a work by Thomas Kinkade, I say, enjoy. But that doesn’t qualify you as a critic.

The art I love — and “love” is not too strong a word — includes some famous and important paintings. I grew up with Picasso’s Guernica when it was hanging at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In my teen years, I visited MoMA often and thought I’d have Guernica to see for my lifetime. But it returned to Spain in 1981. Seeing it stretched across 25 feet of wallspace helped steer me into a life with art.

I loved seeing Jackson Pollock’s One Number 31, also at MoMA, back when abstract art was still seen with suspicion by the public. It hit me like a brick, and I loved its visual busy-ness and textural depth. It was a painting I could lose myself in.

In Boston, I finally saw Paul Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, another panoramic picture. Unlike the Mona Lisa, it makes a stronger affect in person than reproduced.

At the National Gallery in Washington, there are a number of paintings I visit, as if on a pilgrimage. Perhaps the main one is Mary Queen of Heaven by the 15th-century Master of the St. Lucy Legend, an unknown artist (so many were anonymous back then) with a magical ability to create detailed fabric and rich color. It is not one of the superstars of the collection, but it is dear to me. It is 7 feet tall, and busy with detail. I love art that highlights texture and color, and am less drawn to iconography or storytelling for itself (such as features in propaganda). The virgin Mary means nothing to me religiously, but this painting I worship.

All the work of Claude Monet pleases me, but it is the large waterlilies that move me. When I finally got to see the group of them at the Orangerie in Paris, I had to sit down. Two oval rooms with walls banded with waterlilies. It was a holy place.

These are all works that both give me great pleasure, and are also historically important works, anthologized in any art history text.

Yet, some of the art that I love most and that gives me great pleasure is art not especially important, or at least not widely known. There are so-called “local artists” who never get the national reputation; there are artists I know personally and whose work speaks to me in part because I see their personalities so clearly in what they produce.

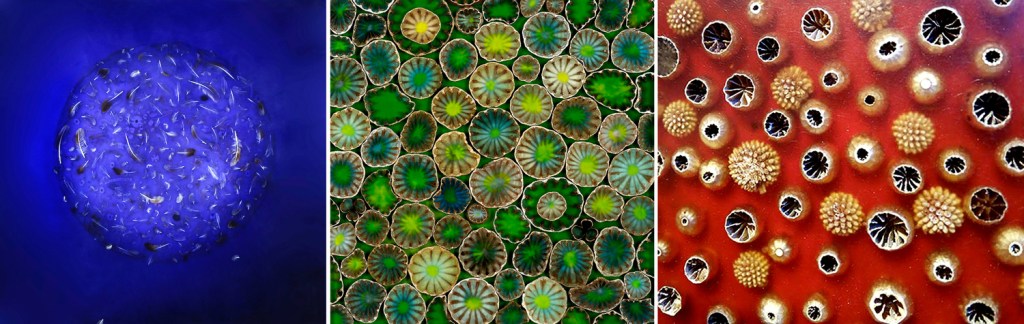

I love the art of Arizona’s Mayme Kratz. I’ve written about her work several times. Mostly, she finds discarded bits of the natural world — seeds, husks, birdnests, grains, twigs, shells — and embeds them in patterns in colored acrylic, finished with a fine sheen. They are intensely beautiful. Kratz makes a living from her work and has buyers and collectors, but I don’t know why she isn’t featured in galleries in New York or Berlin. Her work deserves to be.

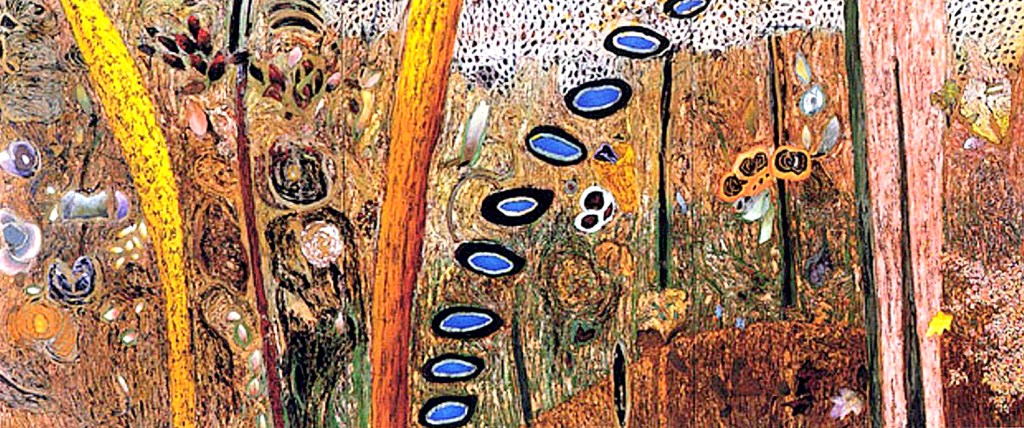

Tucson painter Jim Waid has a growing reputation and has representation outside of Arizona. But his large canvases, electric with color and texture, were featured (during my time) primarily at one gallery in Scottsdale. As I wrote about him for the newspaper, “Is there any reason that David Hockney is ubiquitous and that Jim Waid is not? Waid is clearly as good a painter, and his canvases as original and distinctive, yet Hockney jet sets, and Waid paints in his studio in Tucson.” One of the highlights of my year was the annual Waid show at Riva Yares Gallery.

My brother, Craig Nilsen, is a painter and printmaker from Virginia. I have seen his work all his life and I cannot help but see him in the paintings so particularly and often heartbreakingly. He is now retired, as I am, and I am lucky to own quite a few of his pieces. I love them all.

And finally, my brother-in-law Mel Steele, who has a pretty good reputation in North Carolina, although not always for his best work. He made his living for years selling prints of North Carolina rural scenes. But his real work has always been his abstractions, layers of shapes and colors, creating virtual depth and space on the canvas. I am not alone in enjoying his art, but I feel my life would be much less rich without it.

And so, I feel as if my immersion in art has two channels: One is the official one, where I write for a public and attempt to be somewhat objective; and a second which is what I feel most emotionally connected with.

There are many other examples of work I feel deep in my bones, but I can’t catalog them all. What I can say, is that a life immersed in paintings, as in music, dance, film, theater, architecture and literature, is a life more deeply connected with being human. I am grateful for having been able to make a living writing about it all.

Click on any image to enlarge