My Uncle Stanley had an ambition in life to own a Weimaraner hound. I was only a boy at the time and didn’t quite understand the appeal of such a dog, but for the IBM typewriter technician he was, living in New Jersey in the 1960s, I imagine it had something of the attraction a solid gold toilet had for Elvis Presley. The rest of us had dogs that we lucked into, finding a stray, or getting a mutt from the dog pound. But the Weimaraner was a pricey breed and my uncle wanted one. He finally got one. It was a nice dog, but for me, that’s just what it was — a dog.

Many, I think, have some similar focus in their lives, some object that signifies arrival, or a sense of completeness in life. Most items hold that position only for as long as they are unachieved. Yet there remains a pride in the achievement, even if the reward is rather less than anticipated.

I think of those who have yearned to own a Cadillac. They may live in a mobile home and work as janitor in the local factory, but if they can park a Caddy out front, it will show they aren’t complete failures.

As in the familiar song, St. James Infirmary: When I die, “Put a twenty-dollar gold piece on my watch chain,/ So the boys’ll know that I died standin’ pat.”

The idea of getting that bit you believe you want or need is common. Perhaps it is a $300 Wüsthof chef knife; or a Rolex watch; or a bespoke suit from Hong Kong. Whatever is your icon of either quality or status or style, it chases you through life until you can finally afford it. I certainly have felt it. When I was young, it was a Nikon camera, then a Leica and then a Hasselblad. I finally got each and while I wasn’t disappointed — they are all as good as their reputations — they never quite made that great a difference in the photographs I made.

I imagine that if the People’s Republic of China ever finally get their hands on Taiwan, it will not prove to be quite so satisfying a triumph as they had imagined.

I never chased a particular car or watch, but there are books I longed for. I have managed to get some of them; others still elude me. But here are the big three I lusted after for years.

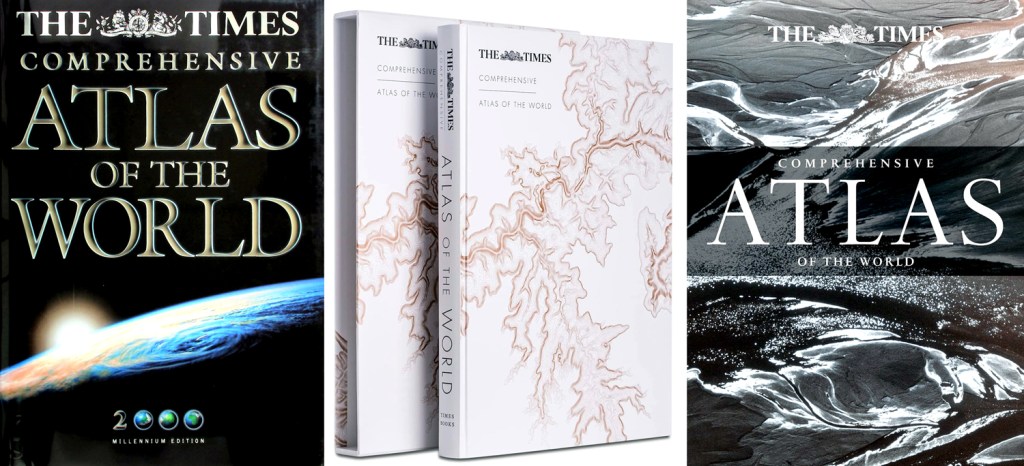

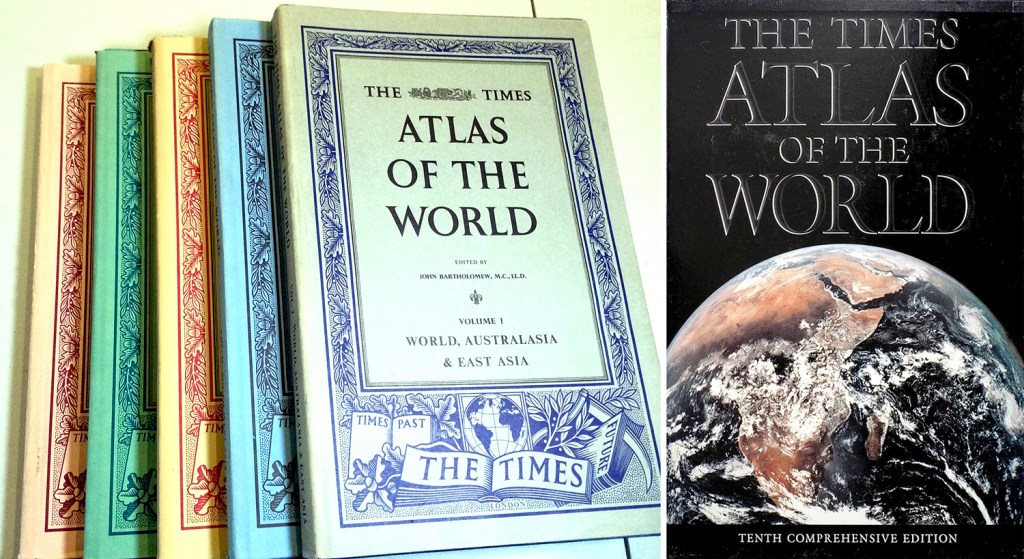

The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World

Beginning in the third grade, I loved maps. And what I loved more than any were the big maps in the classroom that were pulled down like a windowshade, and were richly colored in thick inks — not halftone dots: The green was dark green ink, not a mix of yellow and cyan dots. Mountain regions were a rich chestnut brown. Those maps were beautiful. They may have been out of date even in my childhood, but I didn’t love them for their accuracy, but as art.

Years later, I found something very similar in older editions of the Goode’s School Atlas, where the maps were created using wood engravings, so there were straight-line cross-hatchings for shadings, and again, multi-colored inks for the printing. I saw them as art books. I found a few in old, musty used book stores and I still treasure them.

The very first puzzle pieces I remember, as far back as infancy, were map puzzles, where each U.S. state was a single piece. I took apart and redid that states puzzle hundreds of times, even as, in my infant-tongue the states were Uncle Homer and Miss Thompson.

Later, as a young man, newly empowered with a car and an income, I began traveling, and to aid that travel, I had a Rand McNally Road Atlas. I have updated them every other year or so, but I also acquired vintage versions from 1935 and 1942, which are things of beauty of their own, in two-color printing, with most roads in dark blue and highways in red. I treasure the old ones, while the newer, full-color maps are merely disposable useful tools.

But, out there on the horizon, was the Times Comprehensive Atlas of The World, published in constantly updated editions from 1895 through its 16th edition in 2023. By 1959, the Midcentury Edition of the atlas was a five-volume elephant folio edition measuring 12-by-19-inches. It was the Cadillac of world atlases and it was way out of my price range when I was young. I did manage to get the single volume 10th edition, picked up used.

It was a large, handsome volume. The maps were halftones, so, not as esthetically distinct as the Goode’s, but still, it was by all counts the best atlas on the market. Unfortunately, when I retired, I had to sell off about 75 percent of my library to make the move across the country from Phoenix to North Carolina, and the Times atlas was one of the casualties. Kept the Goode’s, though.

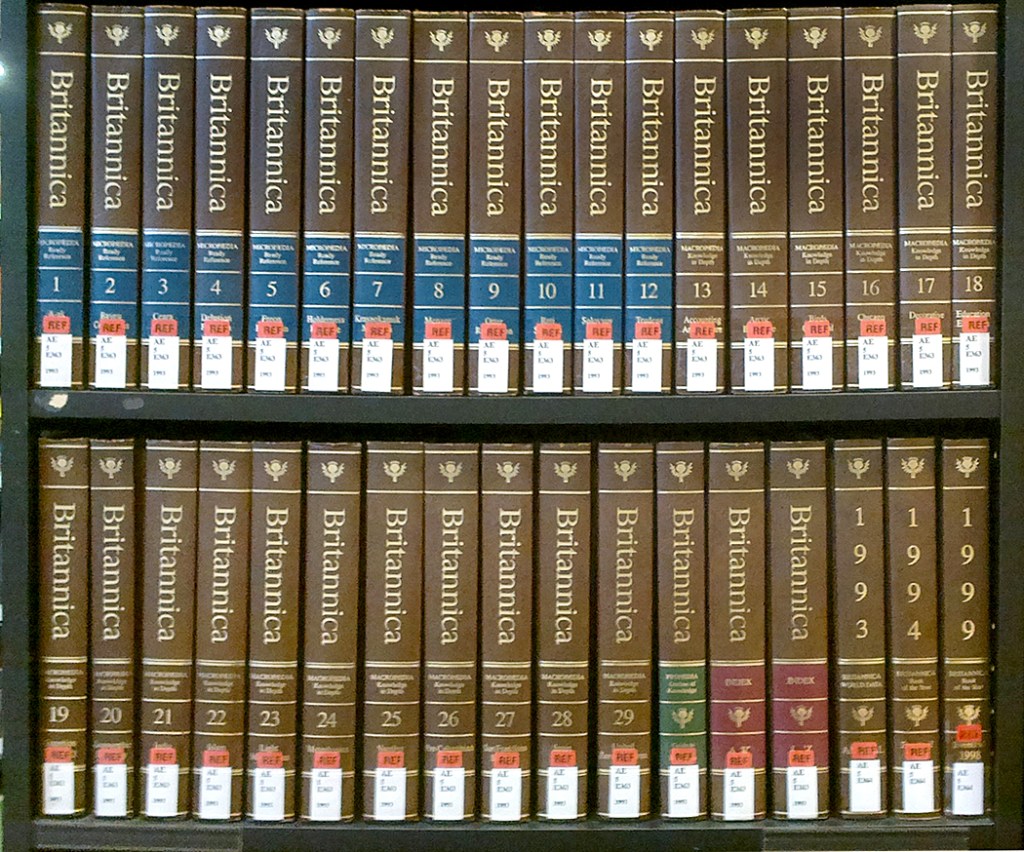

The Encyclopedia Brittanica

By the time I was in sixth grade, I wanted to learn everything. I was young enough still to think that possible. And where would I find all this knowledge? I’d read the encyclopedia.

My neighbors had an old Compton’s Picture Encyclopedia, from the 1930s, which they gave us, and I read it over and over, with its streamlined steam trains, autogyros and biplanes. But even as a kid, I knew the books were out of date. A wonderful long entry on “The Great War,” but, although I was reading it in 1953 or so, less than 10 years after WWII, there was no mention of any of it.

My mother wanted to help, and so, she began buying the promotional supermarket offering Funk and Wagnalls, one per week, for 99 cents each, until we had the full set, cheaply printed and bound. I used them for years to write theme papers for school. But I always knew that they weren’t the “real thing.” For that I needed the Britannica, which was way outside my family’s budget.

I continued lusting for my own Encyclopedia Britannica, all through college, the jobs that followed and into my years at the newspaper in Arizona, when I finally got a set at Bookman’s, a used book store in Mesa. But my enthusiasm was tempered by the fact that the set I got was not the traditional Britannica, but the combined “micropædia” and “macropædia,” in which the entries were divided into the more popular entries, in shorter, easier to read versions — the micropædia — and the more in-depth entries in the rest of the volumes. It felt like a dumbed-down, even trendy version of what I truly wanted. I wanted the Belmondo Breathless and got the Richard Gere Breathless.

Years later, I came across the revised 14th edition, in 24 volumes and its leathery maroon covers and thistle logo, and managed to buy it. This was the real thing, at last. The pride of my collection.

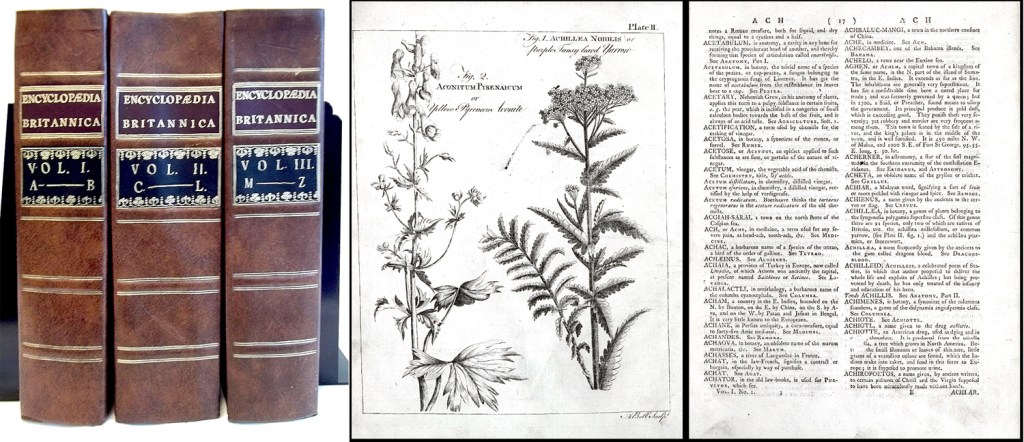

At Bookman’s, I later also found a facsimile version of the original three-volume Encyclopædia Britannica, from 1768. The replica was quite convincing, even including (imitation) foxing on some of the pages. More interesting was evidence that the 18th century project engaged the enthusiasm of its makers early on, and then rather petered out. The first volume covers the letters “A” and “B.” The second includes “C” through “L.” And the third and slimmest volume gets to cover everything else to the letter “Zed.” The facsimile edition was published in 1971.

Then, of course, the internet came along, with its Wikipedia. The Britannica sat on the shelf as a kind of trophy, but largely unused. And when we moved, it was one of the casualties. So long in the getting, so short in the forgetting.

The Oxford English Dictionary

But the real prize, the one thing that I lusted for more than any other, was the Oxford English Dictionary, the 20 volume final word on the English language.

I was a long-time reader of dictionaries. From second-grade on, I loved learning vocabulary. From 8th grade on, I loved learning the etymologies of words, and how they could change meaning over time. The OED contained all that information. Entries were long, involved and gave dozens, maybe scores, of citations, each dated and quoted. A simple word with multiple meanings, such as “set,” went on for pages, and required 60,000 words to describe some 580 senses. The whole of the dictionary was 21,730 pages and 59 million words covering more than 300,000 entries. It was heaven. It was also pricey. The set could sell from $1500 to $2000, depending on where you bought it.

The full OED is still my unicorn. I have never found an affordable used set. But, in the 1970s, the Oxford Press put out a 2-volume Compact Edition, with every four pages of the original OED shrunk photomechanically down to quarter-size and printed four original pages squeezed into each single page of the edition, which required the use of a magnifying glass (included) to be able to read it. The Compact Edition was offered at rock-bottom price as a promotion through a book club, and I signed on, and got my copy.

It is very hard to read, even with the magnifying glass, and the volumes were big and bulky and uncomfortable to use, but at least I owned a version of the OED. This was as close as I got to Nirvana.

I still have the Compact Edition, occupying the upper shelf of a coat closet. I haven’t dragged it out in years, but I still have it, a reminder of those things I once thought would change my life forever. Perhaps they did.

So, what did you always want and did or didn’t finally achieve?

Click on any image to enlarge