Classical music critic David Hurwitz recently posted a YouTube video on works that “reduce me to a quivering puddle of emotional resonance.” He cited 10 compositions that seem to work, no matter how they are performed (although, they can be ruined by a miserable performance).

“The crying can be sadness; it can be happiness. Usually for me it’s a confrontation with something which is so beautiful … it just seems to get to the heart of the universe and makes me weep. What can I tell you? It happens.”

He then invited his viewers to submit their own lists of works that bring on the waters. A subsequent video addressed those lists.

Such lists usually come in round numbers: “Top Ten,” or “The Hundred Best,” etc. But when I made my own list, I realized I could go on for quite some time.

I begin my list with the sarabande in J.S. Bach’s Suite No. 5 for unaccompanied cello. It is a ridiculously simple composition, barely more than a hundred individual notes, almost all unrelieved slow eighth-notes, but notes that plumb the deepest depths of innigkeit — that profound sense of inner subjective experience, of aloneness from the world, contemplation of things beyond words.

The tears come, not from sadness, but from a sense of being left to your own thoughts in the darkness, the knowledge that, no matter how much you love or engage, there is always an awareness of separation. An aloneness we share with everyone else on the planet.

I’ve heard the sarabande, and the suite, countless times, both live and on recordings. The one that always does me in is the version played by Pablo Casals in 1939. Casals was the person most responsible for the resurrection of the score, after he found a forgotten copy in a used book store in 1889, when he was 13 years old. He waited until he was 60 before recording them. There is some fuzz and hiss to the old 78rpm recordings, but the depth of Casal’s playing speaks through it all.

The sarabande has struck many as special, even among the whole of Bach’s works. Cellist Paul Tortelier called it an “extension of silence.” Yo-Yo Ma played it on Sept. 11, 2002, at the site of the World Trade Center, while the names of the dead were spoken, on the first anniversary of the attack.

Second on my list is the final chorus of Bach’s Passion According to St. Matthew, Wir setzen uns mit Tränen nieder, which expresses grief over the death of Jesus on the cross. That chorus transcends religious doctrine so that I, as a non-believer, can internalize the sense of loss, of death, and grieve along with them. “We sit down in tears,” they sing, with a section that also asks for “peace, sweet peace.”

I first head the chorus as film-score music for Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Neorealist retelling of The Gospel According to St. Matthew, a dour black-and-white version, almost word for word from the Bible (and how peculiar that the most successful Christian film should come from a homosexual Communist atheist, but with reverence for the humanity of the story; no Cecil B. DeMille hokum and claptrap for this one).

Grieving is one cause for the waterworks in listeners. How can you not feel the intense sadness of Dido as she faces her own death in Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, in the section known as Dido’s Lament, “When I am Laid to Rest.” It is a ground bass (repeated bass line), over which she sings “Remember me … remember me.” It is heartbreaking.

Alban Berg used his entire Violin Concerto to express mourning over the death of Manon Gropius, daughter of Walter Gropius and Alma Mahler, who died of polio in 1935 at the age of 18. Berg dedicated his concerto “To the memory of an angel.”

It begins quietly on the violin’s open strings, builds to an angry climax, and reaches a point of cosmic acceptance with a quote of J.S. Bach’s chorale, “Es ist Genug” (“It is enough.”)

After all the turbulence of the anger, the simple hymn, albeit harmonized in a very 20th-century way, seems like the peace of the angels, a calm in the universe. I, for one, cannot listen to the concerto without tears streaming down my cheeks.

Although it is written in his idiosyncratic 12-tone style, the Berg Violin Concerto is never simply noise: Even those who hate modern serial music love this concerto. It is music, not theory.

These several pieces work because, while they are expressing their grief over a specific death, they also subsume the rest of us. And there is music which expresses not individual grief, but Weltschmerz — “the sorrows of the world” — that sense that all lives have an end, that life is suffering, that “no one gets out alive.”

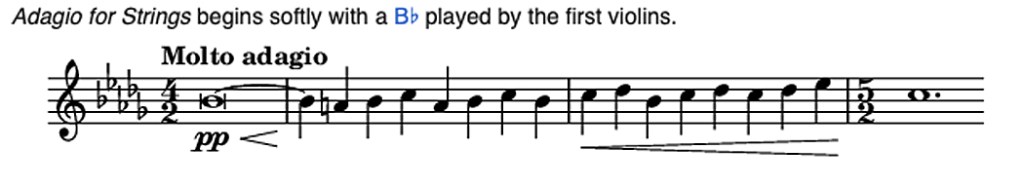

The work that seems to hit everyone in the gut with this is Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. Originally the slow movement of a string quartet, Barber orchestrated it to create the version known best.

The music is simple, barely more complex than a Gregorian chant, but builds slowly to an overwhelming climax, then silence, then a short peroration of calmness and repose. Never a dry eye.

The only problem with the Adagio for Strings is that it has become so popular, played at the funerals of Franklin Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Princess Grace of Monaco, Albert Einstein, and Barber himself. It has become de rigeur for public tragedies such as Sept. 11, The Charlie Hebdo attack, the 2016 Brussels bombing and the Orlando nightclub shooting, and the 2017 Manchester Arena bombing, and in 2020 for the victims of the Coronavirus. To say nothing of how many movies it provides a trigger for emotions, as in Platoon, The Elephant Man and Lorenzo’s Oil. So that, for some, it can no longer be heard innocently, but only with irony, as in its appearance in Seinfeld, The Simpsons, and South Park.

But so far, the Adagio has proved bulletproof. It always works. Emotions pour out. The music is powerful.

And talk about Weltschmerz: Another concerto brings out the emotions almost instantly, and that is Elgar’s Cello Concerto. Unlike most classical music concertos, it opens with the solo cello playing widely spaced E-minor chords, ringing sad and hollow, followed by a short cadenza before the orchestra ever plays a note.

Elgar wrote it in 1919 in distress over the death and destruction of the First World War. It is a musical evocation of the famous lament of British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey in 1914: “The lamps are going out all over Europe and we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.” It is hard, with our distance from the events, and after the Second World War and the horrors of the Cold War, to fathom what a psychological wrench that first cataclysm was for the world, and how much it was clear that everything anyone knew had changed utterly and forever. So much was lost. Elgar’s concerto puts that sentiment into music.

That sense of loss is personal as well as civic, and you sense it in the greatest of Richard Strauss’ Four Last Songs, “Im Abendrot.” It is a song for soprano and orchestra that conveys such a sense of longing and loss that even without the words, the orchestra alone can bring out the tears.

In it an old couple stands on a hill looking at a sunset, a lark flies off into the twilight and the words by German poet Joseph von Eichendorff, say, “Wie sind wir wandermüde — Is dies etwa der Tod?” “How weary we are of wandering — Is this perhaps death?”

There is something of the same feeling (and similar orchestral lushness) in Gustav Mahler’s Der Abschied, the final song of the cycle, Das Lied von der Erde, “The Song of the Earth.” The half-hour song tells of the beauty and permanence of nature and in the brevity of the human life. Even for a Mahler nut like me, who loves pretty much everything the man put on paper, Der Abschied is the single most beautiful and heartbreaking thing that composer ever wrote.

“O Schönheit! O ewigen Liebens – Lebens – trunk’ne Welt!” “O beauty! O eternal loving-and-life-drunk world!” And the voice finally shrinks down to near-silence repeating the word “Ewig,” “forever…” over and over until it and the orchestra dissolve in emptiness.

Mahler himself asked whether the music should even be played. “Won’t people go home and shoot themselves?” he asked. The thing is that the highest art may tell the most dismal tale, yet the beauty of the telling is life-enriching and leaves us weeping but full of joy.

Mahler gave us also a song of such inwardness and reflection in the Rückert Lieder, “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen,” a setting of a poem by Friedrich Ruckert. “I am become lost to the world, with which I used to waste so much time. It has for known nothing of me for so long, it may well believe me dead.” The slow tread of the song, with its repeated incomplete upward motive, leaves you floating between earth and sky.

That Mahler song may not be the deepest expression of giving up on life. That honor has to fall to the final song in Franz Schubert’s song cycle Winterreise, “Winter Journey.” The cycle of 24 songs by German poet Wilhelm Müller collectively tell the story of a romantic young man spurned in love, who travels in suffering through a winter landscape, telling of loneliness, heartsickness, futility, fate, and finally, in Die Leiermann, “The hurdy-gurdy man,” finds an image of utter hopelessness.

“Barefoot on the ice, he sways to and fro, and his little collection plate remains empty. No one wants to listen to him; no one looks at him. … He plays and his hurdy-gurdy never stops.” The piano accompaniment repeats the same figure over and over, with no sense of forward motion, and the singer sings his words over and over with little variation. This is psychological depression at its peak expression. “Strange old man, shall I go with you?” The implication is that the Leiermann is simply Death itself.

But I may be giving the wrong impression. While music of woe may bring on the deepest emotion, so, too, can music of joy and beauty. There is a reason people cry at weddings. When any emotion, from grief to ecstasy, fills the interior space, it can swell and overflow, and the overflow valves in the human being are the eyes. The emotional pressure in the body swells until it cannot be held in check. Tears of joy, tears in the face of beauty.

I remember the words that playwright Peter Shaffer put in the mouth of Antonio Salieri in his play, Amadeus. Salieri overheard the adagio of Mozart’s Gran Partita for winds.

“Extraordinary!,” he says. “On the page it looked nothing! The beginning simple, almost comic. Just a pulse. Bassoons, basset horns — like a rusty squeezebox. And then, suddenly, high above it, an oboe. A single note, hanging there, unwavering. Until a clarinet took it over, sweetened it into a phrase of such delight! This was no composition by a performing monkey! This was a music I had never heard. Filled with such longing, such unfulfillable longing. It seemed to me that I was hearing the voice of God.”

It is an astonishing thing about beauty, real beauty, that it can sit beside the horrors of the world, the miseries, the deaths, the wars, the hatreds and injustices, and make you pause, fill you with emotions and remind you that no matter how bad things are, you still cling to life. The beauty can not excuse the suffering, but in some inexplainable way can somehow balance it. Beauty can stop time and fill you up to overflowing.

Shostakovich wrote his 13th symphony, setting the Yevtushenko poem, Babi Yar, about the 1941 massacre of more than 30,000 Jews by Nazis at Babi Yar, near Kiev. It is a powerful poem denouncing anti-Semitism and the horrors of war and hatred (and a warning about Soviet anti-Semitism). The following movements of this choral symphony take on bitter humor as antidote to bureaucracy and tyranny; the hunger of food shortage; the use of fear by totalitarians; and finally, the difference between amoral careerism and the need for artists to express truth.

This finale is introduced by a flute duet of such sweet delight, such soothing calmness, that although it cannot gainsay the horrors, it somehow balances them. The music itself, while beautiful, is nothing special in itself, but coming as it does at the end of this explosion of the miseries of the world (and especially Stalin’s Soviet Union), is such an unexpected release, it seems a miracle, and with the pressure taken off, at least momentarily, it can only be felt and expressed by its audience in the immediate explosion of waterworks.

Now, all I have to hear is the flute bit, and I instantly recall all that went before, and I weep uncontrollably.

That sense of beauty as counterbalance is the overwhelming sense you can get from the slow movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which gives us 15 to 20 minutes (depending on performance) of stillness in the universe, a slow pulse that seems more cosmic than corporeal. It comes after a terrifying first movement and a relentless scherzo. The world then, after flowing through turbulent rapids, empties out into the calm ocean of the adagio. The release is overwhelming.

It is also the slow motion of the finale of Mahler’s Third Symphony, which, after earlier movements titled “What the flowers in the meadow tell me,” “What the animals in the forest tell me,” What Man tells me,” and “What the angels tell me,” ends his symphony with a half-hour movement, “What Love tells me.”

It is marked “Langsam — Ruhevoll — Empfunden,” (Slowly — Peacefully — Deeply felt,” and moves at a slow tread, first in the strings and building, a half-hour later, with trombones and brass and a final chord that can last to eternity. Conductor Bruno Walter, who knew Mahler and conducted the premieres of both his Ninth Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde, said of this movement, “Words are stilled — for what language can utter heavenly love more powerfully and forcefully than music itself? The Adagio, with its broad, solemn melodic line, is, as a whole — and despite passages of burning pain — eloquent of comfort and grace.”

The Swiss critic William Ritter said it was, ”Perhaps the greatest Adagio written since Beethoven.” Another anonymous critic wrote about the Adagio: “It rises to heights which situate this movement among the most sublime in all symphonic literature.” At its premier in 1902, Mahler was called back to the podium 12 times, and the local newspaper reported that “the thunderous ovation lasted no less than 15 minutes.”

That sense of time standing still reaches a much quieter apotheosis in the slow movement of Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G. With subtle cross-rhythms and a melody that seldom rises above a mezzo-piano, it is entirely hypnotic. The beauty of it brings me to tears almost even just thinking of it.

And there is the sublime beauty of Mozart’s Ave Verum Corpus, a choral work that lasts a mere four minutes in just 46 bars of sighing chromaticism and sotto voce music, and, as one critic put it, is “capable of leaving the listener just as moved as might an entire five-day long cycle of Wagner’s Ring.”

Some of these may work their magic only on my ears, some seem to work for everyone. And there are times when the listener may be too tired, to caught up in other things, or a bad meal or just in a sour mood, when such music can pass by almost unnoticed. And there are times in a concert when I am so tuned in, that almost any music, played well, may bring on the waterworks.

But for me, this music almost never fails. The music triggers some empathetic response, and the emotions shiver to life. I am human; these are human feelings; these emotions are what make us human.

Music can do that better, and more immediately, than any other art.