PART FIVE: THEORY OF RELATIVITY

PART FIVE: THEORY OF RELATIVITY

1.

It was Thanksgiving and Stuart and Genevieve were fixing a big dinner.

Outside, it was a Maine November, dry and crisp but not yet cold. The fallen maple leaves textured the ground at the base of the trees. There was a mackerel sky.

Bernard was there with his wife. Stuart’s younger brother was there, too. Mitch came in from New Jersey with his new lady friend. Bernard’s two children had come, also. Both now grown and Liz had her own children. She came with her best friend, Dell. Jason came with his girlfriend. They all drove in from Allentown. Stuart’s father sat in the corner; he barely moved all day, taking in the scene — probably. It’s hard to know. Bernard and Ellen had picked him up on the way.

It was full house. Mia hadn’t shown up yet.

Bernard: “So, little brother, how’s life treating you?”

Mitch: “Just fine.”

In Stuart’s family, this counted as an extended conversation.

Liz: “Dell, can you take the brussels sprouts off the burner? I have to mix the Jell-O.”

Dell: “Which are the brussels sprouts? I’ve never had brussels sprouts.”

Pots were steaming, with rutabagas, potatoes, brussels sprouts and green beans. In the oven were the turkey and two pans of oyster stuffing. The gravy was yet to be made. That was Stuart’s job. He was the gravy man.

Mitch: “Hey, you’ve got Coltrane here.”

He was flipping through the CD collection.

Mitch: “A Love Supreme. Geez, what music.”

Stuart: “Put it on if you want.”

Thanksgiving was the only holiday Stuart enjoyed. The others seemed like obligations, but Thanksgiving seemed like a warm, humid, cozy indoors played against a cold, dry outdoors: You could feel it when you touched the window.

There was a brief discussion, as Bernie wanted to watch the game, but Mitch wanted to play Coltrane. They compromised and watched silent football with a jazz soundtrack.

Stuart: “Now that’s what I love about Thanksgiving.”

Meanwhile the grandkids were pinging and buzzing their Gameboys. The women gravitated to the kitchen. Mitch’s girl, Jerri, came in to help.

Jerri: “Pie!”

Liz: “Pumpkin”

Dell: “Cherry.”

In the living room, Mitch and Jason had taken to comparing political theory. Uncle Mitch was a Democrat; Jason was a Republican. It is one of the anomalies of history that as the millennium winds down, it should be the younger generation who turn conservative. It is as if time were out of joint.

Mitch: “Yeah? What do you know? You’re just a kid.”

Jason: “Well, I know Bush is going to trounce Gore.”

Mitch: “God help us. We’ll have gone from Reagan to Bonzo.”

Politics brings out the analytic elegance in people.

The doorbell rang and Stuart opened the door. Mia came from the bright blue sunny outdoors to the dark, warm inside, thick with the scent of turkey, dressing and nutmeg and cloves. With her came Michael. Yes, they were still together, 10 years later.

Mia: “Everyone, this is Michael.” Mia went around the room introducing everyone and they all shook hands.

Dinner was a feast; everyone ate till their bellies hurt. Conversation was warm, funny, by turns nostalgic.

To Mia, this was family, even if she wasn’t related by blood to any of them. She knew many of them well — Stuart and Genevieve might as well have been family; Bernie and Ellen; even Mitch, although she had never met Jerri. Others were more peripheral, but Mia knew which was which, for the most part. It was hard, though, to tell the twins apart at that age.

With the meal packed solidly in their collective guts, like sausages stuffed into their casings, the evening wore on. The women put up the leftovers. Stuart told them to leave the pots and dishes; he would get them in the morning. The men sat on the sofa; Mitch’s head was cocked back and a slow stertorous snore echoed in his gullet. Stuart began to talk about ancient Egypt.

“Not now,” Genevieve said, heading him off. It was not bossy, but teasing. He stopped.

After dessert and coffee, when the evening wore down, Bernie and family, along with dear old dad, left for the motel. A pile of others found a place in the guest room or on the sofa, wrapped in a down comforter.

2

Mia and Stuart stayed up late.

“Gen is great,” she said. “But you realize, don’t you, that you have been with her for more than a decade. You are breaking precedent.”

“Well, yes. But I have gotten old. It isn’t as easy to wander aimlessly. And we get to travel a lot, as she gets gigs all over. Spent most of the summer up in Hancock for the Monteux Festival. She got to play the Shostakovich sonata. It was great.”

“She’s a steady presence,” Mia said. “I can’t tell whether Michael is a steady presence for me, or if I’m the steady presence for him.”

“Does it matter?”

“Maybe not.”

They stood over the kitchen sink, piled with dishes. Stuart had his arms up to the elbows in suds.

“Let me tell you about my first official marriage. Before I married your mother.

“I was unfaithful to my first ex-wife before we were married. I loved Ruth, although she drove me nuts. She was always worried about things like window curtains and insurance. She wanted kids; I wanted to continue being able to sleep late for the next 18 years and I knew that her plan would have made that impossible.

“But Ruth was really a great woman. She was beautiful. Had great eyes. And she was smart as hell. Maybe a little skinny. But there was this conventional side to her. In my lovesickness for Ruth, I pretended I didn’t see that, or at least pretended that it didn’t matter. She insisted we wait till marriage. I was so smitten, I didn’t even question that.

“Oh, but there was Helen. This was a different Helen. She wrote poetry. It wasn’t bad poetry, considering we were all just sophomores in college. Helen was not a beginner at love. In fact, she was the ‘college widow,’ as Groucho Marx might call it. A completely free spirit. I fell hard; Helen admitted me to the inner circle — so’s to speak — inner circle: I’ve never heard it called that before — as one of many admirers.

“You should have seen me. I panted like a puppydog, waiting to be patted on the head. Helen and I hitchhiked one week to the coast and spent the nights sleeping in the sand. We made love in the dunes, in full sight of anyone. A fisherman in a passing boat waved to us.

“We left love stains all over campus. Our favorite was a practice room in the music building, and boy, we got lots of practice.”

“Yes, I remember you told me about the Organ Room on campus.”

“At night, it was unlocked for some reason, and we snuck in.

“Oh, but there was Ruth. And I loved Ruth, too. I didn’t know what I wanted. Sensible Ruth or crazy, passionate Helen? Should I go with the sensible choice or should I go with my gonads? Thrill or stability?

“I knew I was not terribly stable, that I was not really a fully mature human being, that I was flamboyant in my irresponsibility, and so I finally decided that I needed Ruth for balance. I did the sensible thing; we got married. I learned my lesson: Never do the sensible thing again.

“I made life miserable for her and without trying, she made it miserable for me. Years later, friends told me they knew it wouldn’t last and I wanted to slap them — Why didn’t you say anything then? But I also knew it wouldn’t have made any difference if they did.”

Mia looked confused.

“Wait a minute,” she said. “Isn’t this what you’re doing right now, with Gen? Aren’t you making the ‘sensible’ choice all over again?”

“Of course,” Stuart admitted. “Of course, I’m doing the same thing all over again. I’m a lot older now, so it’s different.”

“Different?”

“Well, maybe it’s not different. As you get older it isn’t so much you get wiser in the sense that you make better choices, but that you get wiser in that you recognize the fact that you’re never going to get any smarter and you’ll always do the same stupid thing.”

“That’s wisdom?”

“I dunno. Maybe.”

“That’s depressing.”

“No, not really. It’s liberating. That’s the thing about getting older. All the stuff that used to drive you nuts, you let go of. It no longer matters.”

“So, it’s OK to be comfortable in a relationship? Without fireworks?”

“Violas seldom break out in fireworks,” he said. “But I’m happy.”

“But you said it was a mistake.”

“Did I?”

3.

I’m coming out of my duck blind for the last time. I just turned 40; I got tenure. I published a book last year — a new translation — or retelling, really — of Ovid for children. I’ve been living with Michael for about as long as Stuart has lived with Genevieve. I’m not sure it’s a good idea to compare my life with his, but there is no one I’ve known as long or as closely as I’ve known Stuart. He is the only touchstone I have.

This has been a strangely skewed memoir — I have left out so much: my career at the university, several relationships that went nowhere, the whole world of Greek and Roman letters that are so central to my life — because I wanted to focus on this single aspect of my life that has been so muddled. Family. What is it, why is it, does it need to be?

When my dad died, it hit me in a way I didn’t foresee. I always thought of Stuart as my father; he’s the one who was there when I was a little girl, and he has remained there through my life in a way Dan never did. Yet, I felt so odd when I went to visit Dan in the hospital. I saw something in him — gesture, voice — that caught me unawares: They were mine, too. Dan had tried to tell me about it, but I didn’t have ears to hear, or to pay attention. He was dying, after all. Other things seemed more important.

It was the day after that Thanksgiving, when I talked with Stuart’s brother, Bernie, that he brought it all together for me. Stuart and Ellen went to the kitchen to finish cleaning up what we hadn’t washed the night before, and Gen was in her study practicing. The dulcet tones of the viola filled the house like dinner had the night before. Bernie and I sat in the front room and talked.

4.

“What do you think about family? Why is it important? Stuart always says his friends are his family — except for you, he says. You are more friend than family, he says.”

Bernie had bad knees, and sat on the sofa. His hair was mostly gone and his mouth had settled, the way they do as you get older: Younger mouths show off the upper teeth; aged mouths show the lowers.

“I take your point,” he said. “Families can be quite a burden. We have to take care of dear old dad, for instance. He’s barely there anymore. But I have the example of my wife.

“You’ve been with her a long time.”

“Thirty years …”

“Can’t fathom that. Mind you, Ellen’s great. You hit the lottery, as it were.”

“Ellen has a take on family I’d never really considered,” he said. “Family is something different for her. For her, it is where she came from.”

“You mean, like genealogy?”

“Sort of, but she isn’t so much into the family tree as such, or into whether or not she has a coat-of-arms, but rather, that she is made up of the hand-me-downs, genetically, of the ancestors, the piling up of character — of meaning — that has concentrated in her. Her family is her roots, deep in the ground, and she is connected to them as literally as the tree is to the root ball, all of a piece.

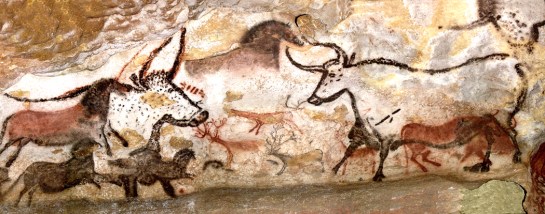

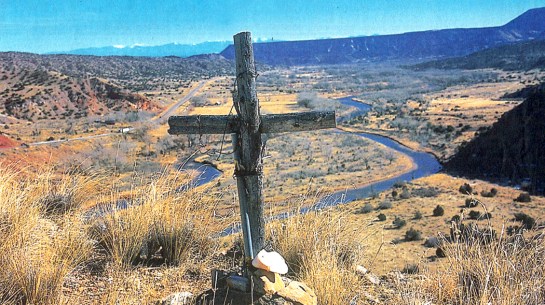

“She sees her hair in her grandmother’s hair, her jawline in her father’s, her love of nature — and, I might add, her stubbornness — in her grandfather. She grew up with her great-grandmother in the house, who was a Civil-War widow, and sees history not in paragraphs on a page in a book, but in her wrinkly skin. She wants to know how her great grandfather came to live in North Carolina, whether he is Scots-Irish, why they eat collards or sing certain hymns as opposed to others. Obviously, this is not all genetic. A good deal is cultural, but I don’t think Ellen makes that much distinction: It is all roots, all the long line of ancestors, which, for her, go back — and I’m not kidding — to Adam and Eve, or whoever you want to pick as the ur-progenitors. Her interest in cave men is part of the same thing. She calls it ‘the long man,’ the person drawn from one generation to the next the same way a plant goes to flower, a flower to seed, a seed to seedling, to plant, to flower, to seed and so on in a continuous recreation of the same life — the same DNA shuffled around — of which she is merely the latest flowering. Or the antepenultimate: She has now sprouted a daughter, and that daughter twin granddaughters. So now Ellen can see she isn’t the end of a long line of ancestry, but only one link in a continuity.

“Thus, family for her isn’t simply the people who she shares Thanksgiving dinner with, as if they were all discrete entities, but rather as if they were the acorns hanging on the same oak tree, in a sense, a single person with multiple incarnations. At Thanksgiving, even if she is alone, she is having dinner with all of them.”

“Well, that is Ellen, through and through, isn’t it?”

“Yes, and it has made me think differently about family. I share your sense of relatives as something you’d rather not have to spend time with. I have chosen my own ‘family’ of friends, who mean a great deal to me. But I also have come to see the ‘mystic bonds’ of family — again, not as a question of whether I want to spend time with them. I don’t, really. But rather as a continuation of a process.

“Looked at another way, I am a bit of my parents planted in the future to grow, and to plant my children there in the future that extends beyond my harvesting.

“I had the oddest experience a few years ago. Did I ever tell you about it? You know, before Ellen, I was married and divorced. We had a son. When we split up, she took our son and I didn’t see him for something like 30 years.”

“I didn’t know.”

Mia was surprised. Bernie always seemed so rock solid. How could he have not seen his son for so long?

“I was young and a prat,” he explained. “So I moved on without much thought of it. Most men are prats when they are young; I was no exception.

“But a few years ago, I got a phone call and on the other end a voice said, “Are you my father?” It was my son. I had not seen or had any contact with him for 30 years.

“Well, Ellen and I went to Austin, Texas, where he was living and we met him and the shock was palpable: He looked exactly like I did when I was his age. Not just in physiognomy, but he wore the same kind of thick-rimmed glasses, the same plaid shirts, the same long hair I had back then. It was uncanny. He was living with a woman who came from the same county in North Carolina that Ellen came from. His house was a mess of books and CDs and DVDs. He worked, at the time, in a used bookstore and was in charge of the classics section and the poetry section. His favorite literature was the classics. The resemblance was uncanny.

“I had always assumed that in the ‘Nature vs. Nurture’ controversy, that nurture was by far the more important. We were raised at a time when we thought, ‘It’s all cultural.’ But here was evidence in front of me that perhaps it wasn’t all cultural. Perhaps DNA ruled not only the shape of our noses, but the preference we might have for Manhattan or New England clam chowder.

“The real clincher came when we walked through his office at the back of his house and there, on the top of a bookshelf, he had a world globe with the ball taken off, turned upside down with Antarctica now at the top, and replaced. I laughed. Back home, on top of my bookshelf in my office was a world globe that I had reversed to put Antarctica on the top. It was almost scary. How many people have done that with their globes? What are the chances that father and son, with no interaction for three decades, would each do the same peculiar thing?”

“So, you’re saying then, that as opposed to the question of whether you choose family or friends, that the question is basically irrelevant: That family is who you are, that ancestry defines your nature and you have family to thank or blame for it.”

“I remember having this discussion many years ago with a colleague. We had both grown up in New Jersey in the 1950s and ‘60s. We shared a good deal of nurture and could understand many of the same cultural references. But he was from an Italian family and I was from a Norwegian family. Despite how much we shared, he had a preference for Fellini films and I had a preference for Bergman.

“Not that I couldn’t appreciate Fellini — I do — but that deep in my bones, I knew the Bergman world; it was my interior world. While the Fellini was tremendous, but exterior to me. There is something in my genes that responds in a family way to the world of Bergman that Fellini doesn’t hit. But it was the reverse for my colleague. Italian genes felt at home in Fellini.

“In the old days, I would have chalked it all up to culture: He grew up in an Italian family and so the folk ways would have felt familiar. But now, I think — it’s only tentative, of course — but I think perhaps it may be something genetic. This may be the collective unconscious that Jung wrote about. The pile of chromosomal tendencies, tastes, judgments, behaviors, that have been reinforced over the generations by the distillation and concentration of DNA.

“I’m sure that upbringing and culture plays a part, no doubt, but I now think that there may be something inherent, that if I had been adopted by an Italian family, I would still feel more at home in Bergman. Not provable in my case, perhaps, but I think plausible.”

“So, I think you are saying, that you are inevitable in terms of family as you are in terms of history, that you may not like the times in which you are born, but you simply have no choice in the matter, and that all those relatives who bore you on holidays are just the titrations of chromosomes and you are thus embedded in your family like raisins in a muffin. No choice. Just is.”

“Yes.”

“Still don’t want them over for dinner.”