“Elbow,” he said.

It is the provisional answer to a question in the best TV series ever made. At least on my list.

The question? “What’s the loveliest word in the English language? In the sound it makes in the mouth? In the shape it makes on the page?” It is the kind of question a writer thinks about, but not so much a civilian. It is the hospitalized crime writer Philip Marlow in Dennis Potter’s 1986 BBC serial, The Singing Detective. “E-L-B-O-W,” comes the answer. Pronounced in the euphonious baritone of Michael Gambon as he talks to his Nurse Mills, played by the young Joanne Whalley.

I had avoided watching the series when it was first broadcast in the U.S. on PBS in 1988 because I thought the title meant it was an airy musical, perhaps in the Doris Day mode. I couldn’t have been more wrong. It is dark and gritty and brilliant. And it is No. 1 on my list of greatest television series.

Of course, any such list, whether Top 10 or “100 Greatest…” are ultimately meaningless and catalog simply one person’s taste. Your mileage may vary. But I’m pretty secure in my choices, with the proviso that although I am 78 years old and was born roughly the same time as television, I haven’t seen everything ever aired, not even all that was broadcast in this country. No one has.

There are a number of popular and well-thought of series I have never seen. Game of Thrones — I am bored by quasi-Medieval post-apocalyptic fantasy. Lonesome Dove — I love Robert Duvall, but mostly gave up cowboys after Hopalong Cassidy retired from the 12-inch black-and-white screen. The Wire — I should probably watch it, but it sounds unrelentingly grim.

But of the things I have watched, here are my top five series of all time. There are some qualifying parameters. I’m not talking about long-running TV series, or notable sitcoms or dramas. So, I’m not including All in the Family or Seinfeld. There are plenty of those, and they would qualify for a different list. I’m talking about limited series presentations, usually with a direct beginning, middle and end, like mini-series or one-offs.

And my taste runs to character-driven shows rather than plot-centered ones. Very few gunfights or car chases and a lot of talking and psychologies. I have nothing against one-liners or action thrillers; they have their place. But I am more taken with more complex stories, something more akin to art than simply entertainment.

And so, here are my top five TV shows of all time, and can all, in their way, be talked about as sharing some of the depth and insight of, say, Shakespeare or Tolstoy.

The Singing Detective (1986) — The six roughly hour-long episodes follow an English pulp fiction writer suffering in a hospital ward from psoriatic arthropathy, who tries to fight his boredom and maintain his sanity by mentally rewriting one of his books — about a private-eye who moonlights as a dance-hall singer — but increasingly hallucinates about a traumatic episode from his childhood during World War II, the suicide of his mother, and a foul deed he committed in school. The episodes become increasingly confused and mixed, punctuated by popular songs from the 1930s and ’40s. The whole is a phantasmagoria of paranoia with some of the most brilliant writing ever put to screenplay.

“Mr Marlow, you can’t deny I’m paying you good money…” “Money. You’re paying me money. Why put ‘good’ in front of it? Who knows its virtue? I don’t know where it’s been. Do you?”

The mystery he is imagining concerns smuggled Nazis, Russian spies, and ladies of commercial morality, all played out in a cheap dive called Skinskapes. The writer’s West Country childhood, with the deep accents and vocabulary of the region, concerns his love for his father and the infidelity of his mother, which he witnesses. Then, there is the interaction he has with his doctors, nurses, and fellow ward patients and most notable with his psychiatrist who tries to fathom the roots of the writer’s hysteria. And then, there is his estranged wife, who visits him in the ward and whom he abuses most horribly. All Osterized into a grand, almost operatic imbroglio, rising to a peak and resolution in the final episode.

The cast is a who’s who of all the actors you will find in later British classic TV shows, such as Midsomer Murders or Downton Abbey. We get to see them younger, before they aged: Patrick Malahide, David Ryall, Gerard Horan, Ron Cook, Janet Suzman, Alison Steadman, Bill Paterson, and, of course, Jim Carter and Imelda Staunton. These are names well known to anyone streaming British TV on Britbox or Acorn or PBS Masterpiece.

The Sopranos (1999-2007) — Over six seasons and 86 episodes on HBO, we followed Mob boss Tony Soprano and his two families — domestic and crime — as they turned obscure New Jersey into a nationally familiar landscape. Hooray for Hoboken.

It is primarily the first two seasons that were memorable, changing American TV viewing habits permanently, and launching a new “Golden Age” of television. Over the quarter-century since its debut, streaming has taken over from network television and made CBS, ABC and NBC into also-rans.

It took great acting and great writing to do this, and we followed Tony as he suffered panic attacks over some ducks in his swimming pool, challenges to his leadership in the mob, various betrayals, both by him and against him, and, most importantly in the first two seasons, the absolutely awful behavior of his mother, Livia (Nancy Marchand), who Rolling Stone magazine named as the “Third Greatest TV Villain of All Time.” I assume she is beaten only by Iago and Satan.

After Marchand’s death in 2000, the show didn’t exactly go downhill, but it never again had the norm-smashing impact it had at the beginning. It was still riveting, but less revolutionary.

Two of its best episodes came in those first two seasons. “College,” in which Tony takes his daughter, Meadow, to college and discovers a mob informant living under witness protection and proceeds to garrote him in the most realistic-feeling depiction of strangulation I’ve ever seen in a film or on TV. It took a long, agonizing time to accomplish and viewers felt every second of it. And, on the other side of the spectrum, “Pine Barrens,” in which Paulie Walnuts and Christopher Moltisanti attempt to dispose of a Russian gangster in snowy South Jersey and get lost in the process. Both episodes are listed in Wikipedia as among the 30 best television episodes ever.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979) — This is all down to Alec Guinness, who defines the role of British spy George Smiley so microscopically that no matter what great actor attempts the part — and Gary Oldman is not chopped liver in the 2011 movie version — it can never be topped or even equalled. Guinness can “say more with a slight parting of his lips than most actors can say while shouting from the rafters,” wrote The New York Times.

The seven-episode adaptation of le Carré’s 1974 novel did away with all the hokey James Bond razzmatazz and gave us slow, believable procedure as Smiley sniffs out a traitor in the British secret service. Le Carré made up all the slang and the spycraft, but made us believe everything must really work this way in the real MI6.

The story proceeds slowly and carefully, and the dramatis personae comprise some of the best and best-known British actors of the time, including Ian Richardson (House of Cards); Patrick Stewart (Star Trek: The Next Generation); Sian Phillips (I, Claudius); Michael Jayston (Nicholas and Alexandra); Michael Aldridge (Last of the Summer Wine); Warren Clarke (A Clockwork Orange); and other stalwarts of U.K. films and television, Bernard Hepton; Ian Bannen, Joss Ackland; John Standing; Anthony Bate and others. It’s a joy to watch them all doing what they do best.

Fleabag (2016-2019) — It isn’t just the Golden Oldies that count. More recently Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s extension of her one-woman stage show became nominated as one of the best TV presentations ever. It is comic, nasty, witty, intensely observant and a punch in the eye of Postmodern meta brilliance.

Her character, never named except as “Fleabag,” clumsily negotiates family, sex, relationships, and grief in ways embarrassingly both egocentric and clueless. And all the while speaking to us, the audience, in private asides — direct progeny of George Burns talking out of the TV at us in his 1950s sitcom.

Its second season may even be better than the first, when she develops a crush on the Sexy Priest (Andrew Scott). In that season’s Episode 3, the priest notices — for the first time anyone in the whole series has done so — that Fleabag is zoning out and talking to the camera, which is a way she has of disengaging from awkward situations. This disruption in the normal contract of fiction between the reality of the story and the reality of the story-telling is a shivering moment, and leads to the resolution of the entire series.

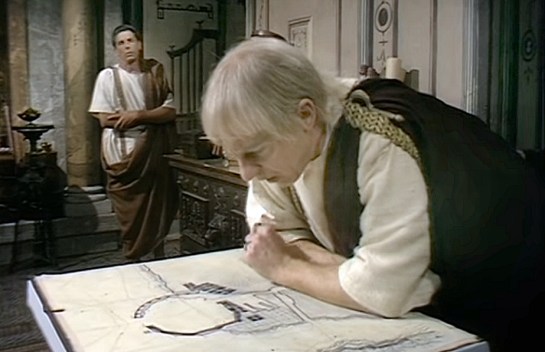

I, Claudius (1976) — I hesitated in picking No. 5 for my list, because there are other legitimate contenders (see below) for the spot. But finally, I have to pick the BBC adaptation of Robert Graves’ two novels about the first four emperors of the Roman Empire (five if you count the foreshadowing of Nero).

It suffers from the early videotape technology, which required a bland sort of lighting. But it compensates by its psychological complexity, great acting and something not normally noticed — great directing.

There is a YouTube video by the name of Moviewise that offers a careful examination of the combined blocking and camera positioning and movement that keeps the action moving seamlessly (Link here). When it is pointed out, you can’t help noticing how craftily it is all done.

Yes, it all plays out as a kind of Roman soap opera, but that is the point — what we think of as grand history is really just today in togas. All the social climbing, back-biting, treachery, power grabbing and hidden agendas we come to see every day on cable news. Caligula seems all too familiar.

Then, there are all the great actors: Derek Jacobi, Sian Phillips, Brian Blessed, George Baker, Margaret Tyzack, John Hurt, Bernard Hepton, Patrick Stewart — all familiar names from other shows on this list and elsewhere.

As I said, lists like this are fun, but they are arbitrary. There has been so much good on the airwaves over the decades. Picking the five best has meant not including Prime Suspect (1991-1996, 2003, 2006), one of the grimmest, most realistic police procedurals ever, which first brought Helen Mirren to a wider public (at least in America — in the U.K., she has been a known quantity since at least the 1969 Michael Powell film, Age of Consent.)

Then, there’s the Mike Nichol’s TV version of Angels in America (2003), with Al Pacino playing villain Roy Cohn. I saw the original Broadway production of the two-part stage play, and later two other versions live, and the filmed version cannot carry the visceral gut-punch of live theater, but it does as well as can be done on film.

And how can you not include Fawlty Towers (1975-1979), probably the funniest 12 episodes of sitcom ever put together, with John Cleese, Prunella Scales, Andrew Sachs and Connie Booth. Ended after two short seasons because you cannot top perfection.

And a special mention to the most literate silly sitcom ever, The Good Place (2016-2020), with Ted Danson and Kristin Bell. Both smart and funny, it seems to have slipped past most viewers on its original airing, but plays with philosophy, life and death in thoughtful and playful ways. It counts for me as one of the best things TV has ever given us. If you haven’t seen it, I highly recommend it.

Finally, there are two made-for-TV series that were later edited and released as theatrical films that most people think of as movies rather than television shows, but they are truly masterpieces and best seen in their multi-episode forms.

First, there was Scenes from a Marriage (1973), by directed by Ingmar Bergman, following the ennui and dissolution of an otherwise happy marriage, with Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson. It was groundbreaking when first made, focusing on all the small details most stories elide past. (One also has to acknowledge the American TV series An American Family, from the same year, which takes a more documentary approach to the same themes, but has a more “reality TV” feel about it, more performative than deep.)

And there’s Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (1982), which is perhaps the richest, warmest, most inclusive family portrait ever screened. Nobody doesn’t love Fanny and Alexander. At 5-hours long, it was shown on Swedish television in five episodes, but later edited to 3 hours for theatrical release. It is considered one of the greatest films of all time, but could equally be added to the list of greatest TV.

So there, you have a challenge. What would make your list of the five greatest TV series of all time?