Happiness is a strange emotion, not a single thing, but really an umbrella term for a diffuse group of hard-to-define states. Periodically, studies are published about which nation is the happiest (usually, it seems, a Scandinavian country.) But what they are measuring is a rather tepid version of happiness. Usually, if we ask if someone is happy, what we mean is an absence of problems — basically a neutral state in which we are not currently threatened, hurting, being oppressed, or worried. “Are you happy?” “Yeah, sure, I guess so.” Enough to eat, a roof over the head, a relationship that isn’t a chore, no pending hospital bills or tax audits.

Really, that is a condition to be wished for, as dull as it sounds. For most people in the world, its achievement would be a godsend. So, I don’t want to downplay such a state. Not getting bombed is a net positive. Yet, there are other happinesses. Falling in love, birth of a child, success at work — these all provide a joyful uplift that raises the psyche above the day-to-day and makes life more radiant, if only briefly. It is a state we cannot maintain over long periods without being considered a bit loopy. So, we return back to the state of happiness that is unremarkable.

But, as adults, we can watch our children at play and recognize in their faces such a state of unreflective happiness that can only break our hearts. Oh, what they don’t know yet about being alive. It’s not just an emotion: The entire body explodes with it.

There is what I might call “body happiness,” which they express in movement, in play, in dancing and skipping, singing, letting out squeals that express the inner state that, as adults, we can only mourn the loss of. “There hath passed away a glory from the earth.”

I mention all this because one of the reasons I listen to music — primarily, for me, what is called classical music — is its ability to evoke emotions in its listeners. They arise sympathetically and are often emotions more subtle than mere language can name. It has been said that music is more precise than words, and I recognize that, whenever I am moved by a quartet or sonata but cannot speak exactly the words that would distort the emotion into easily fixed categories.

A standard symphony moves from thought to thought, emotion to emotion, in ways that express the same sort of progress a story makes, beginning, middle, end. Episodes all build together to a longer, coherent emotional or intellectual ride. Our limbic system moves along with that progress and we can basically take our emotional selves through the moves. The widest range is the most completely human.

And one of the things music can express is that ebullient, body happiness, so that we can feel it again.

Mostly, it jumps out of a single movement in the whole, or even a few bars in the movement, but it is inexpressible joy, and it makes our body move, to tap toes or sway our bodies to and fro, often with a surprised smile on our faces. I think of the finale of Haydn’s Symphony No. 88, for instance, or the scherzo from Dvorak’s Eighth Symphony. I can’t sit still while listening.

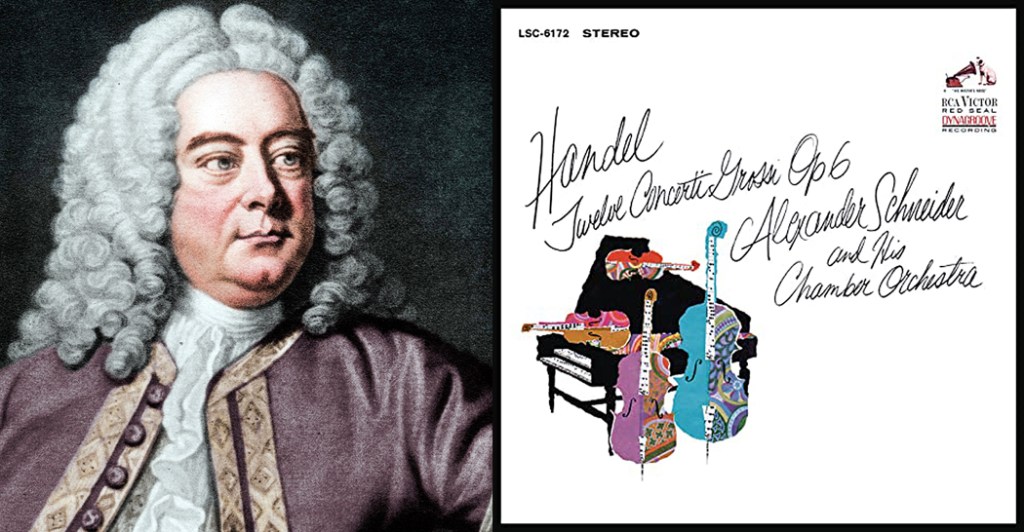

George Frideric Handel has two “happy”numbers in his Acis and Galatea. The opening chorus sings of “Oh the pleasures of the plains, happy nymphs and happy swains,” which extolls the life of the peasants, and a love duet that repeats endlessly, “Happy, happy, happy we.” It all sets up the tragic ending.

But, there are a very few works that take that body happiness from start to finish, works you can play or stream, that will infallibly lift your mood and remind you of the happiness that is upwards of neutral, and can replace all the fret and sorrow for the length of its performance, and usually, for some time after, as you bathe in the memory of its tunes.

There are at least eight of these that I can name, which always leave me uplifted, my senses turned up several notches, and my memory of childhood’s version of happiness is re-animated.

Prime among these is Franz Schubert’s “Trout” Quintet. It bounces and sings through five distinct movements, each of which floods with tune, rhythm and color, anchored by the bottom notes of the double bass.

It was written in 1819, when Schubert was 22 years old, and before the lingering illness that eventually killed him nine years later. The haunting of death darkens the later String Quintet that he completed in 1828, just two months before his death. But the “Trout” is the antithesis of all that: Life giving, life affirming, joyful from first bar to last. What can you do when every tune is an ear-worm. Once inside your body, you carry the “Trout” with you the rest of your life. Play it every time you need it.

Less well-known, but even more relentless is Darius Milhaud’s Le Boeuf sur le Toit, or “The Ox on the Roof.” Milhaud wrote it in 1919 after living in Brazil for two years in the French diplomatic service, and quotes dozens of Brazilian folk songs, adapted into a dance-hall band playing Latin rhythms, complete with güiro. He employs a polytonal technique, where different parts of the band play in different keys at the same time, giving the whole a piquancy and aliveness that has a feeling of spontaneity, like an amateur band in a smoky bar. It’s always just about to come apart.

Written in the Baroque form of ritornello, with an 8-bar tune coming back over an over between alternate dances, it has some 20 Brazilian tunes buried in it, with infectious beats that express the unabashed happiness of a sweaty dance hall. Evybody dance now!

Mostly we think of Johannes Brahms as a sober German burgher writing symphonies with the seriousness required of höchste Deutsches Kunst. But the boy could let his hair down, which he did with two sets of vocal quartets, Liebeslieder Waltzes, op. 52 and op. 65.

Brahms made his living, early in his career, when he moved to Vienna, as leader of various choruses such as the Singakademie and Musikverein, for which he wrote tons of choral music and songs. So, he had a popular streak in him.

The 33 songs, each no longer than a minute or two, celebrate bourgeois domestic love in tunes so meltingly gemütlich that you will have them running through your head for days. They were meant to be sung in homes or in taverns, so they are best with normal voices, not the operatically trained soloists that so often record the set. “Ich gäbe dir so gern hunderttausend Küsse” — “I long to give you a hundred thousand kisses.”

When Georges Bizet was a mere stripling of 17, he wrote a Symphony in C as an exercise for his studies at the Paris Conservatoire. It was never performed in his lifetime and ultimately forgotten about, until it was rediscovered in 1933, and performed two years later by Felix Wiengartner, a suitable conductor, whose first name means “happy.”

Bouncy and tuneful from first note to last, it has proven hugely popular since then, and one wonders why Bizet never had it published, in fact, never even mentioned it. It is a masterpiece, but not on one of those marble pedestals, but the kind that makes your ears grateful to be on your head. It is breezy and fluent and just makes you happy to be alive.

Georges Balanchine choreographed it for the Paris Opera Ballet, and I was lucky enough to see the New York City Ballet perform it with a live orchestra at the Palais Garnier in Paris, (where it was first performed in 1947). One of the highlights of my life.

Also a youthful work is Serge Prokofiev’s Classical Symphony, written in 1916 when he was a conducting student at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. When one of his teachers, Boris Asafyev, mused “that there is no true joyfulness to be found in Russian music,” as Prokofiev wrote, he responded with one of the happiest works ever written by a Russian.

And so, he wrote in his diary, “I composed a new finale, lively and blithe enough for there to be a complete absence of minor triads in the whole movement, only major ones.”

It displays what is often called the composer’s “wrong note Romanticism,” with catchy tunes and ascerbic harmonies, and was meant to mimic the spirit of Haydn and Mozart. What a joy.

Much shorter, at merely five minutes, but so fresh and lively as to become its composer’s most frequently performed piece, the overture Leonard Bernstein wrote to his musical Candide just can’t stop laughing, and teasing, with bubbling wit and elan.

The musical (or operetta — it could never entirely make up its mind and went through multiple reworkings) never quite caught on the way West Side Story has, but its overture, shaped as a mock Rossini overture, is irresistible.

Johann Strauss II produced music the way a lawn sprinkler sprays water. The “Waltz King” composed over 500 waltzes, polkas, quadrilles, and other types of dance music and several operettas, all of surprisingly consistent craftsmanship.

No one in his right mind, though, would sit for all of it; before too long the program would become monotonous: How do you tell one polka from another. That is, except for the large handful of truly memorable masterpieces, all of which will raise you spirits and make you want to dance.

I mean, the Blue Danube, the Voices of Spring, Tales of the Vienna Woods, the Artist’s Life, the Kaiser Waltz — a CD full of the best Strauss is a must-have for any collection. It’s hardly surprising that Brahms envied Strauss’ gift for melody. Each is basically a tone poem in three-four time. Lift the spirits, make you smile and move your body.

Finally, there is Benjamin Britten’s Simple Symphony, which displays a childlike joy in just spinning tunes, which is hardly surprising, since he wrote those tunes when he was a child, between the ages of 10 and 13. When he turned 20, he reworked the tunes into this four-movement suite for strings, with movements titled “Boisterous Bouree,” “Playful Pizzicato,” “Sentimental Sarabade,” and “Frolicsome Finale.” It premiered in 1934 with Britten conducting.

Since then, it has been recorded dozens of times, usually as a filler on discs with other Britten pieces.

There are other joyful pieces, but these are eight that come immediately to mind. They are each available in videos on YouTube, and worth seeking out, especially if you’re having a bit of a down day.