The foundational mythology of the United States belongs to the cowboy. An argument can be made for the Founding Fathers, but they are understood more as history than as myth. And by myth I don’t merely mean something that isn’t “true,” but as a mental model that we have absorbed as the definition of what makes us American. We are more John Wayne than we are John Adams.

Like many of us, I grew up on Westerns, although because I am in my 70s, my foundational Westerns were those from the 1930s recycled in the 1950s on television. I grew up knowing who Ken Maynard was, or Buck Jones. Back then, TV stations were starving for content to broadcast, and the pile of old Westerns filled the Saturday morning hunger. Those younger than me likely didn’t have such a cinematic indoctrination. Later TV Westerns became their version.

But, since I wrote a blog piece about TV’s Gunsmoke, (link here) I have been thinking about Westerns and their role as our national psychic subconscious, and about how the fictional version differed from the historical. And what is more, what that shift means, culturally.

It has not always meant the same thing, and the evolution over time describes the changes in America’s perception of itself.

I believe there were distinct eras of Westerns, that have evolved over the past two centuries. These versions of the West overlap, and all of them have been present from the beginning, or near enough. But the preponderance of each defines each era.

The West began in upstate New York with Natty Bumppo, or Hawkeye, as he was known in The Last of the Mohicans, and gave us the prototype of the rugged individualist. He morphed into Jim Bridger, Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett and various mountain men living in the wilderness.

Jim Bridger; Joseph Walker; Jim Baker; Jim Beckwourth

These heroes played out the myth of how we conquered a vast wilderness with rugged individualism and tenacity. It grew into the myth of Manifest Destiny.

After the Civil War, when economic exploitation of the West began in earnest, with mining and cattle industries, the cowboy took over, with adventurous exploits popularized in a thousand dime novels. Certain names begin showing up with regularity, including Buffalo Bill, Wyatt Earp, Jesse James, Belle Starr. These elided into the early Western movies, including The Great Train Robbery (1903) and Across the Plains (1911), which starred Broncho Billy Anderson, the first cowboy movie star.

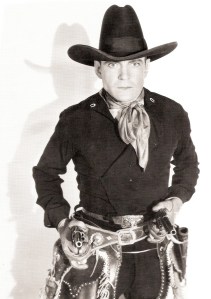

And a split in the myth. On one hand, you had William S. Hart, who attempted a level or realism in costume and plot (matched with a high level of sentimentality), and on the other hand, you had Tom Mix, the show-biz cowboy all duded out with fancy kit.

The difference was between movies made for general audiences and those aimed at children, mainly young boys. Mix brought glamour to the Western, with fancy cowboy duds and sparkling saddlery to his horse, Tony.

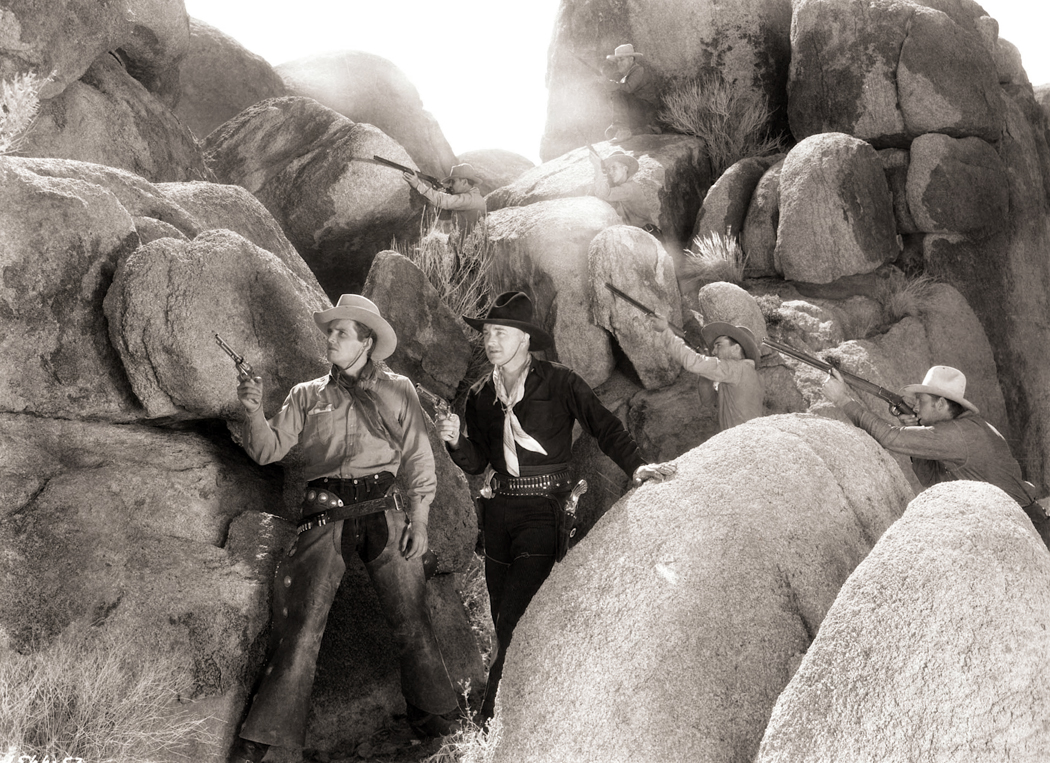

That split continued into the sound era with hour-long Saturday matinees with Hoot Gibson, Bob Steele and dozens of others, including John Wayne, who made scores of cheap oaters and even took to trying out as one of the singing cowboys that were briefly popular.

Through the 1940s, the cowboy movie became stereotyped with stars such as Roy Rogers, Gene Autry and William Boyd as Hopalong Cassidy. There was little attempt at realism. Sometimes they actually fought Nazis.

These were the cowboys wearing shirts with crescent pockets and shoulder fringe, and often sported a six-gun on each hip.

All that carried over into the television era, with a skein of popular Westerns mostly aimed at kids: The Lone Ranger; The Cisco Kid; renewed popularity of Hopalong Cassidy.

Meanwhile, there were always Westerns made for grown-ups, too. From John Ford’s Stagecoach and Howard Hawks’ Red River, through the Budd Boetticher films with Randolph Scott. There was Shane, and High Noon, and Winchester ’73.

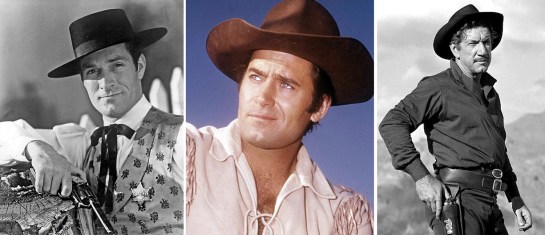

Initially, the lone hero version carried over into the TV era, also, when The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, with Hugh O’Brien, kicked off a decade of evening programing with cowboy heroes, such as Cheyenne, Maverick, Have Gun — Will Travel, Bat Masterson, and The Rifleman. And, of course, Gunsmoke. You can name a dozen others. The market became glutted and then, suddenly, it seems, Westerns were shot dead.

There came a cultural shift. Maybe it was the Vietnam War, maybe it was fatigue with the cowboy cliches, but when Westerns eventually did return to the silver screen, they took a dark turn. There had been revisionist Westerns before. Indians weren’t always the bad guys. But starting in the 1960s, with films such as Ride the High Country (1962), A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and the subsequent Spaghetti Westerns, Hang’em High (1968) and ultimately, The Wild Bunch (1969), the new Western was brutal, filled with low-lifes and lots, and lots of grime.

“McCabe & Mrs. Miller”

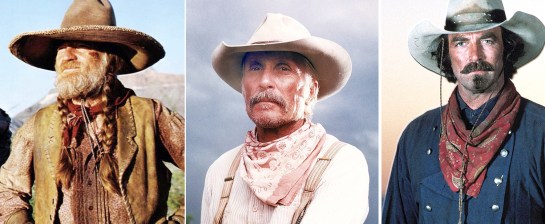

The trend continued through McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) to Unforgiven (1992). Even the more positive films like those from Larry McMurtry novels or with Tom Selleck attempt a more naturalistic view of the times in which they were set.

Of course, there’s a good deal of overlap in the eras. It’s a question of what predominates in what decade. There have been revisionist Westerns from the earliest years, but this view of the overall shape of the Western in American consciousness over time is, I believe, basically accurate.

What is not accurate, though, are the Westerns themselves. Admittedly, they were never really intended as realism: They are myth and they are national epic. Our equivalent of the Iliad or the Kalevala. Even those attempting fidelity to historical fact ultimately underline the myth more than the fact. “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

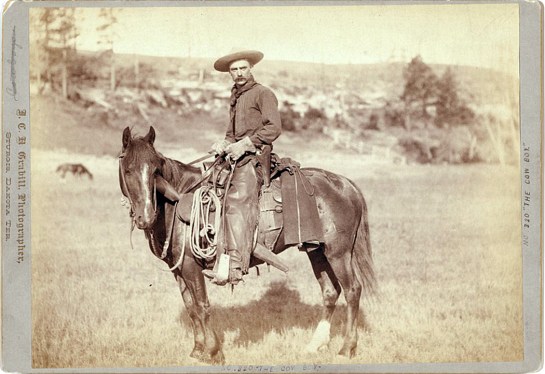

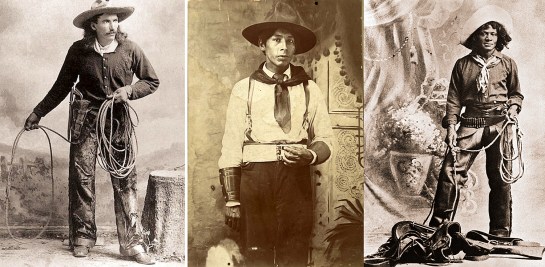

Actual cowboys

As a kid, I loved the cowboy movies, but as an adult, I am bothered by them. I try to remember they are not meant to be documentaries, but crystallizations of myth, and you don’t expect myth to be realistic. You don’t ask Hercules if he has a mortgage.

Yet, there are sore thumbs that stick out for me in almost all filmed Westerns; four of them — aspects that scream out: “No, this isn’t the way it was.” And perhaps that shouldn’t matter, but these things make it difficult for me to appreciate Westerns the way I did when I was a kid.

I have four primary gripes. They are: economy; geography; ethnic diversity; and language. Let’s take them in order.

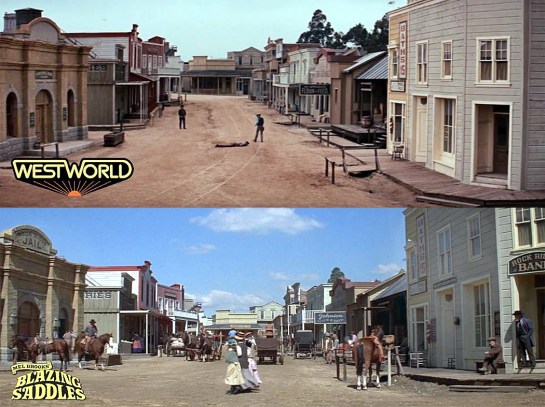

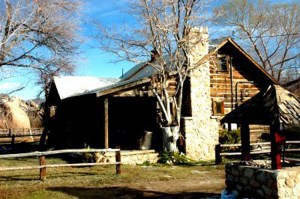

Two movies, same location

Towns exist in Western mainly to stand in for civilization. It’s where the people are — the people largely left undefined. They stand in front of general stores or the saloon while the heroes and villains play out the ritual of the gunfight. The same set can be used and reused in many pictures, even as diverse as Westworld and Blazing Saddles. The Western movie town is just the stage set for the plot.

But actual towns are built for economic reasons. There was some industry that needed workers and the workers needed services, and so, towns grew. But in most Western movies, there doesn’t seem to be any functioning economy. There are references to cattle and ranches, but aside from giving rustlers something to do, they barely show up as economic factors.

While the standard movie Western town has its saloons, its general store, its hotel and restaurant, its stable and blacksmith, there is never a thought to where its residents get the money to pay for their drinks, meals, gingham or horseshoes. A town doesn’t grow for just no reason.

Even Dodge City, in the 1870s, when Gunsmoke is supposedly set, had a mayor and council and a police force. There would also likely have been an elected sheriff for Ford County and a judge, to say nothing of at least two lawyers, advertising on the front page of the Dodge City Times in 1878.

Sometimes it is downright preposterous. Consider Clint Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter. Its town is built on Mono Lake in California with no economic base at all — just a hodgepodge of buildings erected near a salty lake that cannot even provide drinking water for the residents.

“High Plains Drifter”

Or, one of my favorites, the supposed farm built in Monument Valley in Arizona, in The Searchers. The idea of such a farm is ludicrous — not made better because the landscape is supposed to stand in for Texas.

“The Searchers”

Again, there is a reason towns were built where they were. On rivers for shipping; near mines to provide supplies and provisions; along railroads to ship cattle; near army forts to unload soldiers of their pay.

As seen in the movies

My second beef with Westerns is its geography. Most of the Western tales we have historically took place in the most boring landscapes imaginable, in Kansas, Nebraska, Missouri, Texas.

What the actual working West looked like

But such places are not very photogenic. And so, we move them lock, stock and barrel to the Rocky Mountains, the Desert Southwest or California’s Alabama Hills with the Sierra Nevada in the background.

“Gunsmoke”

Even Gunsmoke, set in Kansas, sometimes shows a mountain range off in the distance sighted down the main street. (I’ll discuss Dodge City in more detail in Part 2 of this essay, to follow). Matt Dillon is sometimes shown accompanying a prisoner, for instance, across the Rocky Mountains or into the desert, hundreds of miles from his jurisdiction. To say nothing of the months it would take to ride there on the back of a horse.

In the 1950 film Broken Arrow, Jimmy Stewart rush back from Lordsburg, N.M., to Tucson, Ariz., and somehow manages to pass through Sedona, Ariz., on the way — a detour of several hundred miles. Clearly Sedona was more photogenic than the Wilcox Playa or Benson.

Wilcox Playa (left); Sedona, Ariz. (right)

As in so many Westerns, the West is just a mental landscape, where any buttes and saguaro cactus will do as a setting.

As a sidenote, related to the geography: Cowboys stranded in the desert reach for their canteen and take a slug of water, or else hold it upside down so we can see it’s empty. I lived in the desert for 25 years and can tell you water is a big deal. Driving through Death Valley one July, I became so dehydrated I developed a headache and was beginning to become disoriented. I had to drink a full gallon of water to recover. A few swigs from a canteen is basically meaningless.

The third and fourth distortions are perhaps less important, but they nevertheless stick out for me when I’m watching an old Western. There is the lack of ethnic diversity and the matter of speech.

Cowboys: Vanilla, Native American; African American

It’s been documented that about a quarter of all cowboys were African-American. They don’t much show up in the movies (John Ford had his Woody Stroud and at least that was a nod to the fact). And another 20 percent were Mexican and many were Native American. In the towns, segregation was normal, even if the working cowboys out on the plains were mixed. Virtually all the laundries and restaurants in the Old West were run by Asians, mostly Chinese. Other ethnicities were notable factors in various troubles, as the Irish clashed with the English.

Finally, there is the language spoken in 19th century America, which was much more formal than we take for normal now. In the Western movies, the actors tend to speak in the manner current when the films were made, and that changes over time, just the way the hats went from 10 gallons to three pints, and the brassieres just kept getting pointier.

The evidence from letters and from novels written during the period tell us that people spoke in longer sentences with fewer contractions. At home, you might relax when talking to your spouse or children, but in public, you attempted to be correct. Even the illiterate miners and farmers spoke more formally.

This last bothers me less, because if Randolph Scott or John Wayne spoke as they would have in the Old West, the audience might laugh, or at least yawn. How often have you heard parodies of Ken Burns’ Civil War, when they read letters soldiers wrote home? What was normal speech in the 1870s sounds utterly archaic, even stilted, to our ears.

Next: Part 2 — A look at the historical Dodge City