I have been listening seriously to classical music since 1965, and I have attended hundreds of concerts and recitals since then. Most of those were enjoyable, well-played, musical and provided emotional nourishment, yet almost every one was ultimately digested and forgotten. How could it be otherwise? It takes an exceptional performance to register permanently on the psyche, so that, even 60 years later, they are still resonant in the memory. Now that I am 77, I think about them again.

I grew up in a household with very little music, outside of watching Perry Como or Dinah Shore on the TV. But my high school girlfriend was a musician. She was studying bassoon with Loren Glickman, the man who played the opening notes of The Rite of Spring on the recording conducted by Igor Stravinsky. (She later studied with Bernard Goldberg, primary bassoonist with the Philadelphia Orchestra — she was the real deal). She later went on to work with both PDQ Bach and Philip Glass.

She and I often took the bus into Manhattan to attend concerts. We heard Emil Gilels play the Liszt sonata at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and we went to the very first PDQ Bach concert at Carnegie Hall, hearing both the Concerto for Horn and Hardart and the cantata, Iphegenia in Brooklyn. (For about 20 years after that I went to at least one PDQ Bach concert each year, no matter where I was living). But most of all, we went to the New School concerts led by violinist Alexander Schneider. Tickets were $3 and we could afford them.

And on Christmas Eve, Schneider held an annual midnight concert which allowed me to escape to New York and avoid the boring evenings with my coffee-drinking repressed Norwegian aunts and uncles.

Schneider has always remained my ideal of committed musicianship. He led his chamber group from his seat, with his leg wrapped around the chair leg like the serpent of a caduceus, leaning forward into the music with the intensity of a man defusing a bomb. The music was always exciting. (To this day, I seek out the rare Schneider recordings, such as his Handel op. 6 Concerti Grossi and his Haydn quartets. Schneider was a force.)

New York Times critic Howard Klein wrote about Schneider at the time, “… the playing was that rare ideal of single-mindedness, give-and-take, technical polish and heart. There were a few slides to Mr. Schneider’s melodic playing, just enough to remind one of his romantic tradition. Some scholars might object to the rhythmic liberties that were taken, those marvelous pauses, the slackenings of pace, then the eager striding forth into a fugue, or slipping into a dance rhythm. But this was not romantic Handel, just human warmth. As usual, Mr. Schneider was totally consumed with playing, putting his back into every bow stroke and exhorting the others from his chair to join in the fun. Mr. Schneider is one of the city’s most valuable musicians.”

To this day, Schneider remains my touchstone.

I owe a lot to that first serious girlfriend, but high school romances notoriously don’t last, and this one didn’t, but the music did. I became a serious classical music junkie, going to concerts, recitals, chamber music, and buying endless reams of LPs, tapes and CDs.

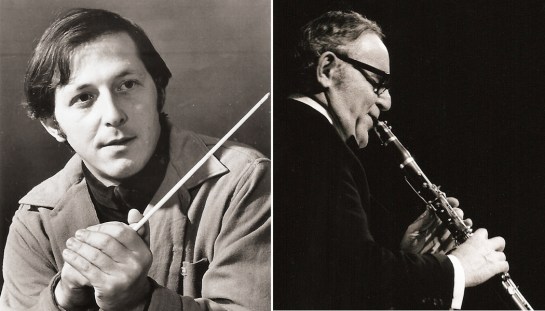

Shelly and Benny

In my college years, most of the music I heard, at Greensboro Symphony concerts, under first Sheldon Morgenstern and then Peter Paul Fuchs, was what you would expect from a community orchestra, although I was still happy to hear the music live. I also heard Benny Goodman play the Weber Clarinet Concerto in F-minor there (and after intermission, play the rest of the evening with his jazz trio).

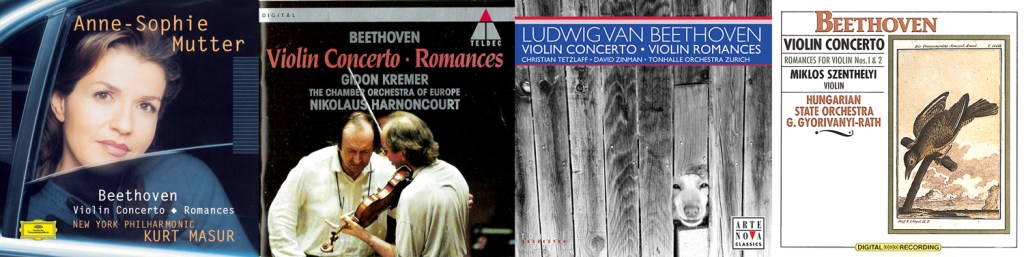

Morgenstern became director of the Eastern Music Festival held each summer at Guilford College in Greensboro, where I was a student, and I heard some world-class soloists come to play with the festival orchestra. The Hungarian Wunderkind Miklos Szenthelyi played the rarely heard Bartok First Violin Concerto and I fell in love with it. Szenthelyi was the most dignified soloist, with the most erect posture I’ve ever seen and played like the music was the most important ever written. It was wonderful. Szenthelyi is now the elder statesman of Hungarian violinists. It has been that long.

Beyond the EMF, one concert stands out from that time. A still-teenage Yo-Yo Ma played both Haydn concertos with the High Point Symphony, one before intermission and one just after and the tunes became ear worms for weeks. Yo-Yo Ma has been a constant ever since, and I have heard him live over and over throughout my concert-going life.

Over the next decades, I moved around quite a bit, often with low-paying jobs, or none at all, and could not often afford tickets. But I still managed to hear Bernstein and the New York Phil play La Mer, and later the same orchestra under Kurt Masur play Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night and Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony. Masur had a reputation as a mere Kappelmeister, a time-beater, but he played Beethoven’s smallest symphony as if it were a tiger as big and muscular as the Fifth. I was surprised and blown away. Ever since, I have had greater respect for the power possible to be found in the Eighth.

Haitink and the LSO

There is a class of musician whose recordings have a reputation for being bland, but hearing live, they take the chances they never do for records. Masur was one. Bernard Haitink was another. All the CDs I had of Haitink were safe and, while well-played, were kind of boring. But then I heard him with the London Symphony at the Salle Pleyel in Paris playing the Eroica with all the fire and passion that could be wrung from the piece. Completely changed my mind about the Dutchman, although it didn’t make the CDs better.

I have to admit that my cherished Yo-Yo could be that way, too. Not that his recordings are bad or boring, but they never capture the buzz and excitement of hearing him live, where he is electric. I heard him playing the Dvorak concerto in Phoenix and I was in tears, almost shaking with emotion after hearing it. It was one of the greatest concert performances I ever attended. His recording of the concerto is really good, but nothing like the live beast.

He has recorded the Bach cello suites three times over his career. The first two are dependable, even excellent, but I’ve heard him doing them live several times and the metaphor again shows up: Played with the intensity of someone defusing a bomb. In his third recording of the six suites, he finally got something of that adventurous power into the CD.

In Seattle, I got to hear the Berlioz Requiem, a piece, because of its logistical demands (expanded orchestra and chorus, four extra brass bands at the four corners of the hall and eight tympani blasting away) I never expected to hear live. It may not have been the best performance of the piece ever, but it yanked my hair back. In the late 1970s, when I lived in Seattle, my regular date was a former professional violinist, turned bicycle messenger, and we went to many concerts together. Unfortunately, although we were good friends, she played for the other team.

By the late 1980s, I was living with my late espoused saint in Phoenix, Arizona, and was the art critic for the major daily newspaper, and later became to classical music critic as well. When you don’t have to pay for your tickets, you get to go to a lot more music. And I heard some great music, not only from local Arizona musicians and from touring groups, but because the paper sent me all over the country, I got to hear music in Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Boston and Philadelphia (and Boulder, Colo., too).

One of the most unforgettable experiences was hearing the Philadelphia Orchestra under Wolfgang Sawallisch play Richard Strauss’ Don Juan. If I ever needed to be persuaded that live music offers something recordings cannot, it was the great horn call in Don Juan, when eight French horns sound off in unison and one doesn’t just hear the sound in one’s ears, but vibrating through the fundament: It was music with a physical presence of a brick wall. No recording can capture that shudder. You have to be there.

I heard Maurizio Pollini in LA playing a first half of all the Chopin Preludes and a second half doing Stravinsky’s Two Scenes from Petruschka (with an intermission of over an hour while, from the lobby, we heard a piano being tuned to his satisfaction in the emptied hall) and ending with the Prokofiev Piano Sonata No. 7. That was the single most daunting program I had ever heard up to that point.

At least until I heard pianist Jeremy Denk at Zankel Hall, part of Carnegie Hall, when the first-half of the recital was Charles Ives’ Concord Sonata and the second half Beethoven’s Hammerklavier — two of the longest and most difficult pieces in the repertoire. He then re-played the “Hawthorne” movement of the Concord Sonata as an encore. His fingers must have been bloody stumps after all that.

I later heard Denk in Scottsdale playing Beethoven’s Eroica Variations, and showing their comic side, and several Ligeti etudes, showing that composer was more than the film score to 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Some of these memorable cases come in pairs, like the Denk’s.

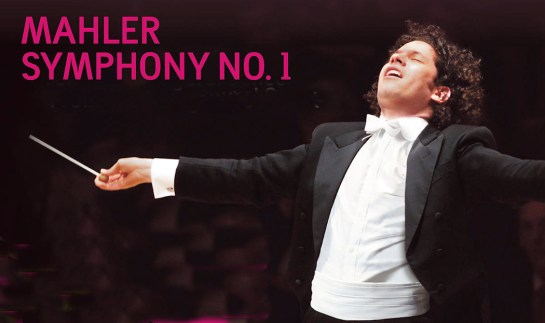

At Carnegie Hall, I heard the Israel Philharmonic play the Tchaikovsky Fourth Symphony under Gustavo Dudamel, and it was pure magic. The 80 or so old Israeli pros were turned back into teenagers by the young enthusiasm of the Dude. They played their hearts out for him. At the end, Dudamel did not take the customary audience bows, but ran up into the orchestra, shaking the hand of every musician, making them all stand up and accept the applause.

Later, with the LA Phil, I heard him lead the Mahler First. These were two of the greatest orchestral concerts I ever heard.

One might expect great sounds from these orchestras, but two of the best live performances I have under my belt came from the Phoenix Symphony and its concertmaster Steven Moeckel, under the direction of Music Director Michael Christie. Moeckel played the greatest version of the Beethoven Violin Concerto I ever heard live, perfect in every expressive detail, and powerfully emotional. I was so blown away that I came back the next night to hear it again, but the magic had passed. It was a very fine performance, but not the same. You are not allowed back into Eden.

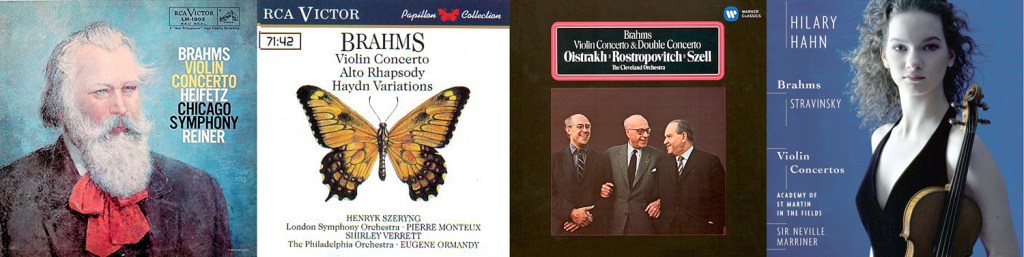

Several times, I had lunch with Moeckel and we talked of many things. He mentioned that he had always wanted to play the Elgar concerto, a piece I didn’t know, having always thought of Elgar as a stuffy English imperialist. But he persuaded Christie to let him do it, and I was transfixed and realized how much I had been missing all my life. The Elgar Violin Concerto is one of the five or six greatest ever written, up there with Beethoven, Brahms, Sibelius, Tchaikovsky, Berg, and Mendelssohn. And Moeckel’s performance couldn’t have sold it any better. It changed my musical life.

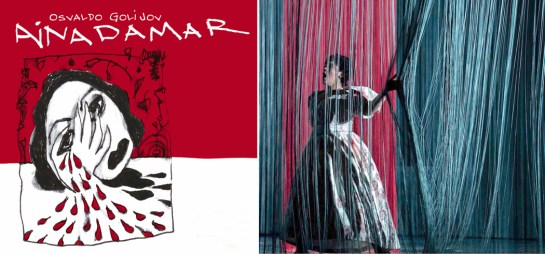

Then, there were two concert opera performances by the Phoenix Symphony and Christie. They engaged Dawn Upshaw to sing in Osvaldo Golijov’s Ainadamar, about the death of Spanish poet Gabriel Garcia Lorca at the hands of the Fascist forces of Franco.

As the music critic for The Arizona Republic, I often had issues with conductor Michael Christie over 19th century classics — Christie had not a Romantic bone in his body — but he was brilliant with contemporary music. I fell in love with Golijov’s eclectic style.

And Christie led a great semi-staged version of John Adams’ Nixon in China, one of the rare contemporary operas to make it into the mainstream repertoire. What a great piece, and the Phoenix Symphony played the daylights out of it.

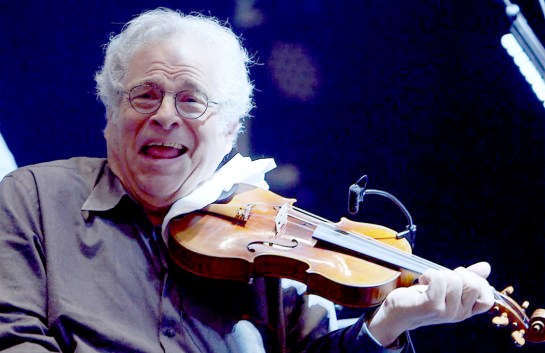

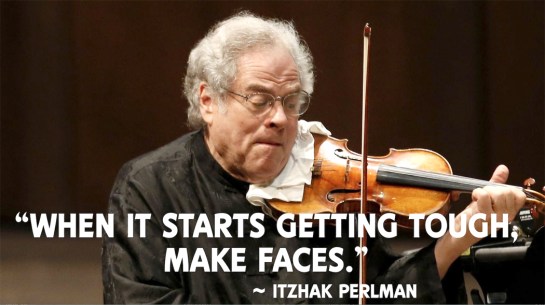

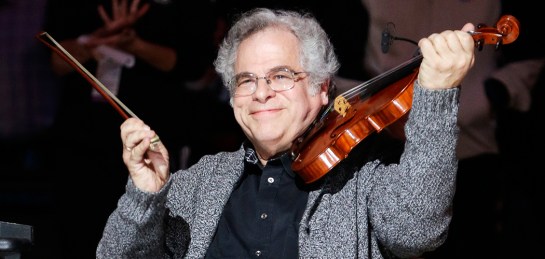

Twice I heard Itzhak Perlman give recitals in Mesa, Ariz. and each time the same thing happened. He opened with a slight sonata, at the first recital a Bach sonata for violin and keyboard and at the second, one of the op. 12’s of Beethoven. I don’t remember which exactly. Perlman played them expertly and even brilliantly, but he just didn’t seem all that involved. I thought, Oh, he’s playing for the boonies and just phoning it in.

Then, the second piece on the program he played like the Greatest Living Violinist, with all the deep engagement, excitement and power anyone ever had. I realize those first pieces were just warm-up. In one recital, it was Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” Sonata and in the other, it was the Strauss Violin Sonata, a piece generally ignored as turgid and overlong, one of the composer’s less inspired works. Well, not when played by Perlman: This was one of the great musical experiences of my life. Geezus! Who knew this was really great music? If I ever had any doubts about Perlman, I lost them completely.

Of course, all that makes up for after intermission, when Perlman puts on his embarrassing Borscht Belt act. The program just says, “selections to be announced from the stage,” which means the violinist plays a series of short schmaltzy pieces once played by the likes of Fritz Kreisler, Ole Bull or Bronislaw Huberman, catchy virtuoso show-off pieces that once fit on a single side of a 78rpm record: Hora Staccato, Liebeslied, Salut d’Amour. And worse, Perlman spends even more time with a pile of dad jokes and cornball puns, as if he really wanted to be a baggy-pants vaudeville comedian rather than a great fiddler. A comic he is not. I shoulda left at intermission with the warm memory of the Strauss still in my mind.

Finally, I want to mention three pianists I heard, whose appearances have permanent real estate in my psyche.

The first is Andre Watts, who I heard several times, but once at the Scottsdale Center for the Arts playing the same Liszt sonata I heard Gilels play at the beginning of my listening life. This time, I understood what I was hearing, and watching Watts’ fingers on the keys, dancing and pouncing. It was a wonderful, performance of clarity and power.

Second, quite different, was Olga Kern playing the Rachmaninov Paganini Rhapsody with the Phoenix Symphony. It is clearly a 20th century piece, but often played as if it were late Romanticism, like his famous concertos. But it is an ironic masterpiece, and Kern played it with such lightness and humor that it was reinvigorated. And the audience gasped at the audacious ending when Kern began standing up even before knocking out the last cadence as if it were an afterthought. Yes, it was a coup de theatre, but it worked and perfectly summed up the tone of the piece as she played it.

And third, a problem performer. You never know what you’re gonna get with Lang Lang. He is often seen as a flashy product of PR and promotion, and doesn’t help himself by often showing off and posturing for audiences, making faces as he stares at the ceiling and waving his arms around. I’ve heard Lang Lang live four times and sometimes he is very good and earns his credit, and sometimes you just wanna slap him. But one time, he played the first Chopin concerto with the Phoenix Symphony and time stopped still for the entire slow movement. Dead still. The world disappeared. Eternity opened up. It cannot be played better or more affectingly than Lang Lang did it that evening. I am forever grateful for what he gave me — one of the greatest performances I ever heard.

Of course, the next time he came to town, it was the other Lang Lang who showed up.