Recently, Turner Classic Movies ran a cheesy science-fiction film I had never seen before. I grew up on bad sci-fi movies from the 1950s and always enjoyed them, in the uncritical way a 9-year-old watches movies on television: Quality never entered the picture. At that age, oblivious there even was such a thing. It wiggled on the screen; I watched.

But this film was released in 1968, too late for me. When I had gone off to college, the only films I watched were snooty art films. And so I never got to see The Green Slime. Now, here it was, and it was prodigiously awful. Actor Robert Horton fights an alien invasion of tentacled, red-eyed monsters.

Everything about The Green Slime was awful: the acting, the lighting, the set design, the special effects — and, of course, the science. Or lack of it. There was the garish color of sets and costumes and the over-use of the zoom lens, the way of made-for-TV movies of the era. I have outgrown my open-hearted love of bad science fiction. I stared in wonder at the horribleness I was seeing on the TV screen.

And it was the acting, more than anything, that appalled me. Why were these actors so stiff, wooden, even laughable? And something I guess I had always known, but never really thought about jumped to mind: Actors are at the mercy of writers. The dialog in Green Slime was stupid, awkward and wooden.

There is some dialog so leaden, so unsayable, that even Olivier can’t bring it off. Robert Horton, while no Olivier, was perfectly fine on Wagon Train, but here he looked like he was lip-synching in a foreign tongue.

“Wait a minute — are you telling me that this thing ‘reproduced’ itself inside the decontamination chamber? And, as we stepped up the current, it just … it just grew?”

I remember, years ago, thinking that Robert Armstrong was a stiff. I had only seen him in King Kong and thought he was a wooden plug of an actor (not as bad, perhaps as Bruce Cabot, but still bad. But years later, I’d seen him in other films where he was just fine. Even in Son of Kong, he was decent. But no one, absolutely no one can pull off a line like “Some big, hardboiled egg gets a look at a pretty face and bang, he cracks up and goes sappy!”

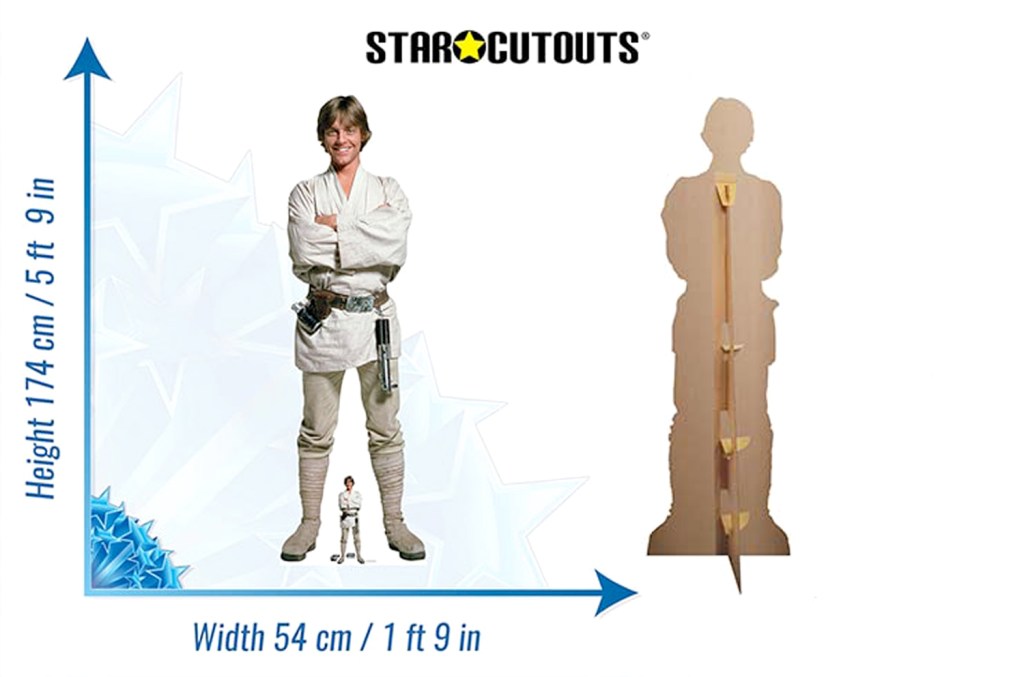

Even in a famous movie, clunky dialog can make an otherwise fine actor look lame. Alec Guinness and James Earl Jones may be able to pull off the unspeakable dialog of the original Star Wars, but for years, I thought Mark Hamill was a cardboard cut-out. It was only when seeing him in other projects I realized that Hamill could actually act. I had a similarly low opinion of Harrison Ford because of what he was forced to mouth in those three early franchise films. George Lucas did them no favors.

There is certainly a range of talent in movies and some genuinely untalented actors who got their parts by flashy looks or sleeping with the producer. But I have come to the opinion that most (certainly not all) actors in Hollywood films are genuinely talented. Perhaps limited, but talented, and given a good script and a helpful director, can do fine work.

One thinks of Lon Chaney Jr., who is wooden, at best, as the Wolfman. But he is heartbreaking as Lenny in Of Mice and Men — perhaps the only chance he ever got to show off what he was actually capable of.

“Lon Chaney was a stiff, but he had Lenny to redeem him,” said my brother Craig, when we discussed this question. Craig can be even more critical than me.

He continued, “I’ve been trying to think of the worst actors ever — someone who has never said a word like a human being. There are a lot of people who got into a movie because they were famous for something else (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Joe Louis, Audie Murphy) so it’s hard to judge them fairly as actors, like you can’t criticize a pet dog for barking the national anthem but not hitting the high notes. But even Johnny Weissmuller was pretty effective in the first Tarzan; Elvis had Jailhouse Rock where he actually played a character; and Madonna can point to Desperately Seeking Susan without shame. (Everything else, shameful. There just isn’t enough shame in the world anymore.)

“There are any number of old cowboy stars who couldn’t speak a believable line of dialog and that can’t be totally blamed on the writing. (Gabby Hayes rose above it.) There are bad actors who still had some life and energy about them that made them fun to watch. Colin Clive was silly, and he made me giggle, so he was entertaining. And Robert Armstrong. But there’s just no excuse for Bruce Cabot.

“I’ve never actually seen a Steven Seagal movie,” Craig said, “but I know enough to say with conviction that he should have been drowned as a baby.”

I said Craig can be tougher than me, but here, I have to concur.

“It’s probably not fair to pick out silent movie actors for being silly and over the top, but there is Douglas Fairbanks to prove you can be silent and great.”

Silent acting was a whole different thing, and hard to judge nowadays. As different from modern film acting as film acting is from acting live on stage. The styles don’t often translate. John Barrymore was the most acclaimed Shakespearean actor in America in the early years of the 20th century, but his style on celluloid came across as pure ham. (Yes, he was often parodying himself on purpose, but that doesn’t gainsay what I am saying about acting styles).

Every once in a while, I see some poor slob I always thought was a horrible actor suddenly give an outstanding performance. Perhaps we have underestimated the importance of the casting director. A well-placed actor in a particular part can be surprising perfection. There is creativity in some casting offices that is itself an artform. You find the right look, voice, or body language, and a minor part becomes memorable. Some actors are wonderful in a limited range of roles. I can’t imagine Elisha Cook as a superhero, but he is perfect as a gunsel.

And Weissmuller was the perfect Tarzan before his clumsy line reading became obvious in the Jungle Jim series. I am reminded of Dianne Wiest in Bullets Over Broadway: “No, no, don’t speak. Don’t speak. Please don’t speak. Please don’t speak.”

Keep in mind, actors are subject to so many things that aren’t in their control. In addition to good writing, they need a sympathetic director, decent lighting, thoughtful editing, even good costume design. Filmmaking is collaborative and it isn’t always the actor’s fault if he comes across like a Madame Tussaud waxwork. I’ve even seen Charlton Heston be good.

In reality, I think of film actors much as major league ballplayers. The worst baseball player on a major league team may be batting under the Mendoza line, and even leading the league in fielding errors, but in comparison with any other ballplayers, from college level to minor leagues, he is superhumanly talented. Even Bob Uecker managed to hit a home run off Sandy Koufax. I doubt any of us could have done that. And so, we have to know who we’re comparing them to.

I saw a quote from Pia Zadora the other day (she just turned 70) and with justifiable humility, she said, “I am often compared to Meryl Streep, as in ‘Pia Zadora is no Meryl Streep.’” Still, compared to you or me, she is Bob Uecker.

I have had to reassess my judgment of many actors. I had always thought of John Wayne as a movie star and not an actor. But I have to admit, part of my dislike of his acting was disgust over his despicable political beliefs. And I thought of him as the “cowboys and Indians” stereotype.

But I have now looked at some of his films with a clearer eye, and realize that, yes, most of his films never asked anything more from him than to be John Wayne — essentially occupying a John Wayne puppet suit — but that when tasked by someone such as John Ford or Howard Hawks, he could actually inhabit a character. “Who knew the son-of-a-bitch could actually act!” Ford himself exclaimed.

But there it is, in The Searchers, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Red River, The Quiet Man, Rio Bravo, The Shootist. Those were all true characterizations. (Does all that cancel out The Alamo or The Conqueror or The War Wagon, or balance all the undistinguished Westerns he made? We each have to judge for ourselves).

Even in his early Monogram oaters, playing Singing Sandy, he brought a naturalness to his presence that is still exceptional in the genre (and researching Wayne, my gasts were flabbered at how good looking he was as a young man. So handsome he was almost pretty. And that hip-swinging gait that predates Marilyn Monroe. “It’s like Jell-O on springs.” It seems notable that so much feminine could become the model of such lumpen masculinity.)

And even great actors have turned in half-ass performances, or appeared in turkeys. In Jaws: The Revenge, Michael Caine has to utter things like, “Remind to tell you about the time I took 100 nuns to Nairobi!” Caine famously said, “I have never seen the film, but by all accounts it was terrible. However I have seen the house that it built, and it is terrific.”

Even Olivier had his Clash of the Titans.

Actors have to work, and they don’t always get to choose. “An actor who is not working is not an actor,” said Christopher Walken. The more talented actors sometimes get to be picky, but the mid-range actor, talented though he or she may be, sometimes just needs the paycheck.

I sometimes think of all the jobbing actors, the character actors of the 1930s, working from picture to picture, or the familiar names on TV series from the ’50s and ’60s — the Royal Danos, the John Andersons, the Denver Pyles, dressed as a grizzled prospector for a week on one show, going home at night for dinner and watching Jack Benny on the tube, and then driving back to the set the next morning and getting back into those duds. And then, next week dressing as a banker for another show, putting together a string of jobs to make a living. And all of them complete professionals, knowing what they are doing and giving the show what it needs. A huge amount of talent without ever having their names above the title.

Royal Dano times four

And so, I feel pity for those actors of equal talent who never broke through, or who were stuck in badly-written movies and couldn’t show off their chops. When I watch reruns of old episodic TV, I pay a good deal more attention than I ever did when I was young, to all the parts that go into making such a show. I notice the lighting, the editing, the directing, and most of all, the writing. The writing seems to separate, more than anything else, the good series from the mediocre ones. And how grateful those working actors must feel when they get a script that gives them a chance to shine.