I was once taken aback, talking with my young twin granddaughters about what movies they liked, that they refused, flat out, to consider any movie made in black and white. Not even a question. Jamais. Never.

For them, black-and-white meant antique, superannuated, something with no relevance to their lives. They wouldn’t even see a current movie if it was in black and white. Life was color; monochrome was irrelevant.

There are other disqualifications that some people maintain. “Read any good movies lately?” They won’t see a film with subtitles, which, of course, cuts out an entire half (at least) of all movie history and some of the greatest films ever.

But by far, the biggest disqualification for the majority of filmgoers is what are called silent movies — movies made from the invention of the medium through roughly 1930, when sound synchronization became the standard.

Without sound, dialog becomes disruptive title cards held motionless for long moments, long enough that the slowest readers in the audience can parse their way through; audio clues, such as traffic noises or train whistles are mute; and worse — actors have to act like semaphore signals to convey their thoughts and feelings. Silent movie acting seems grotesquely over-the-top, more like pantomime than anything we now consider proper acting.

There are other problems, too. In the earlier days of movie-making, frame speed was not standardized, and to complicate matters, most cameras were hand-cranked, which means that the idiosyncratic crank-timing of the cameraman could vary quite a lot. This meant that for decades, long after sound had taken over, and movies began showing up on TV, the old films were projected at the wrong speed, too fast, making everything herky-jerky.

And, because the studios that made those old films never thought of them as anything but disposable entertainment, there was no incentive to archive them or care for the old prints. Add to that, they were made with flammable nitrate film stock, which deteriorated over time, and that there were several devastating studio fires that consumed whole catalogs, what is left is often only a fossilized remnant of what the old films actually were. As a result, an estimated 70 percent of all the movies made before 1930 are lost. Ceased to be. Gone to meet their maker. Joined the bleedin’ choir invisible.

And what survived was seen most often in poorly made copies of copies, bleached out, scratchy, grainy and out of focus. As if silent film technology was roughly akin to the Stone-Age chipping of flint arrowheads.

But that is not what they were when they were made, as we have seen when film restoration has brought us clean prints of some of the more important movies from the era. The photography was as good as anything done currently. The motions of the actors, when projected at the proper speed seem less silly.

You can look at the development of cinema from its earliest beginnings in the 19th century as a constant advance, not only of technology, but of the esthetics of film. At first, a stationary camera just records a few things in front of it. Later, the camera learns how to move. Film learns to tell stories and directors figure out how to edit bits of film together to make those stories move faster and express more. Wholesale changes in blocking, acting, lighting, editing, camera angles and motion all add to the growing sophistication of the art. There are the traditional mileposts in this development: the close-up; the intercutting; the over-the-shoulder back and forth; the use of double-exposure; and of matting.

By the time sound came in, intermittently beginning in 1927 or so (the dates are hard to pin down, depending on how complete the process was and which competing technology was used), silent film had become a fully developed art form, capable of expressing a huge range of thought and emotion. In fact, the advent of sound caused more problems than it solved, and the constraints of microphones and movie-set noise, took away some of the expressive possibilities of the silents.

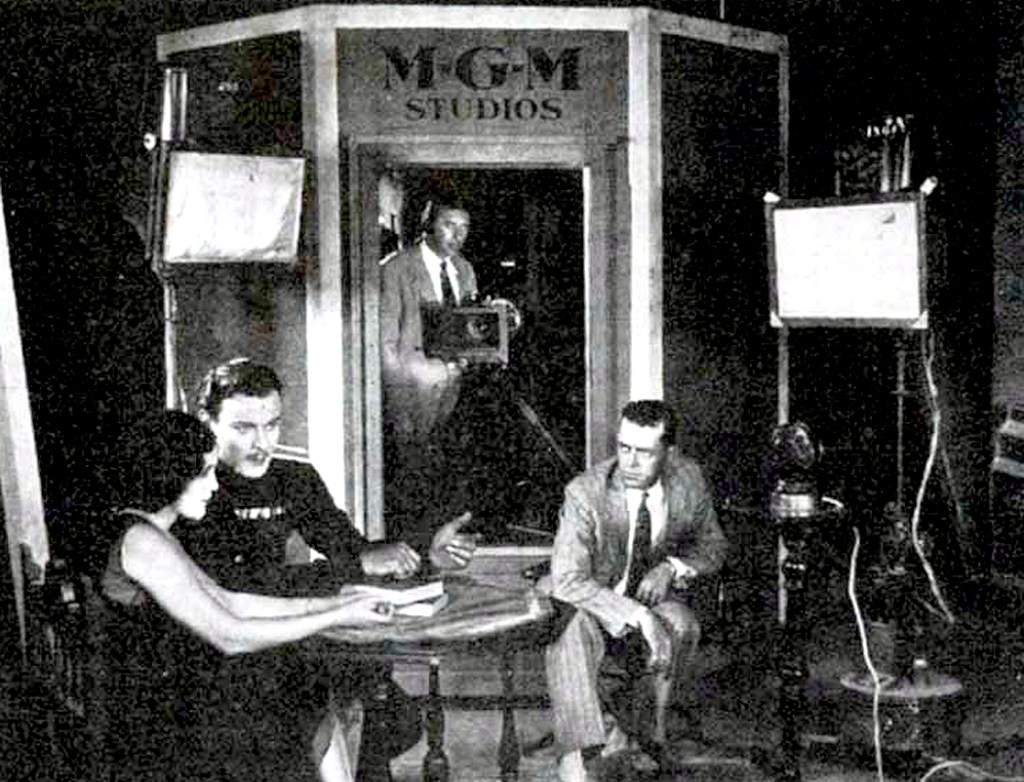

Cameras tended to stay still (they often had to be ensconced in stationary booths or sound-cancelling “blimps” so that the microphones wouldn’t pick up the noise of the machinery) and actors needed to stay still near the microphones. Films became more stagey and set-bound. Early sound films often looked more like recorded stage plays.

Worse, because sound made dialog possible, much was explained rather than shown and talkies became rather talky. The best continued the old dictum, “show, don’t tell,” but it became economically advantageous to let the tongues do the talking rather than the images.

Alfred Hitchcock, who had been making artistically sophisticated silent films, initially thought that “the silent pictures were the purest form of cinema,” and the first talkies were little beside “photographs of people talking.”

All this has been well covered by myriad books and videos about the history of Hollywood. But there is one aspect of silent films that has too often been neglected, and that is that they were never silent films.

During their era, movies were always accompanied by either a live orchestra playing in the pit, a pianist, or an organist. Major features usually had a bespoke musical score that was distributed along with the film, so that orchestras in the large theaters could play along with the movie. In smaller venues, a piano or organ reduction would be provided. For lesser films, music publishers provided regular cues — short bits of piano score describing certain types of action or emotion — for the in-house pianist to improvise from.

The process was very like the incidental music written — often by major composers — for stage plays. Mendelssohn’s music for Midsummer Night’s Dream, or Grieg’s for Peer Gynt, for instance. Several major composers, such as Camille Saint-Saens, also wrote scores for movies.

Or more apt, like the music that accompanied ballet. Tchaikovsky or Leo Delibes or Prokofiev would write music to order, according to the needs of a dance scenario. “I need three minutes of mazurka for Act 2,” the composer might be told, and would produce it on order. We think of composers being divinely inspired by their muses and pumping out symphonies, but really, they often made a living as subcontractors, part of the team that produced popular entertainment. Even Beethoven wrote incidental music and ballets.

So, the tradition of writing music for films was much like that for ballet. It would be silly to imagine Swan Lake with no music, only dancers. But nobody would ever call ballet, “silent theater.”

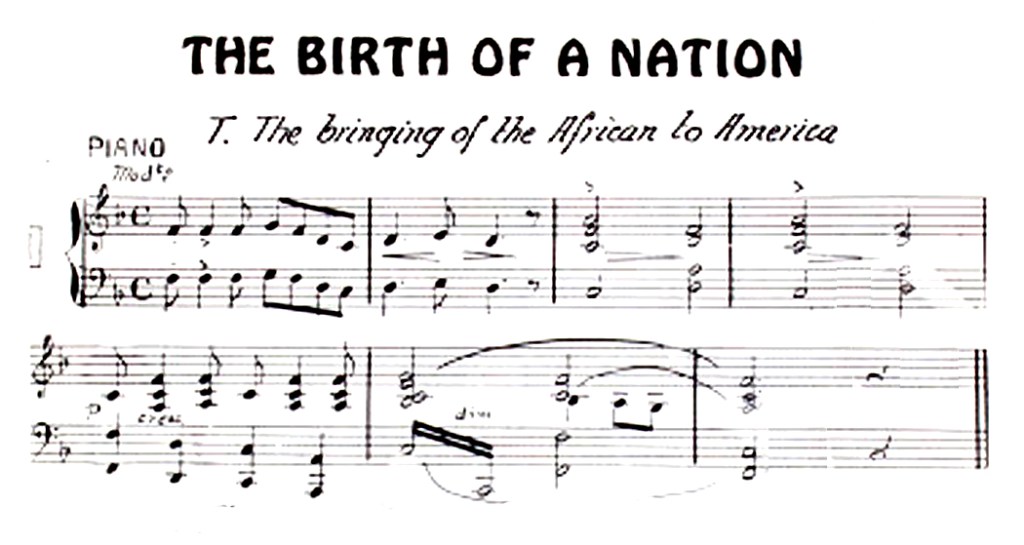

But the first time I ever saw The Birth of a Nation was at my college film series where it was run with no sound. I complained to the projectionist that he forgot to turn on the audio and he looked at me like I was an ignoramus. “It’s a silent film; there is no sound.” Yes, there is, and it was written for the movie by composer Joseph Carl Breil who created a three-hour-long musical score made up of adaptations of existing works by classical composers, new arrangements of well-known melodies, and original composed music. (The British Film Institute’s Blu-Ray restoration of the film includes Breil’s music). (Although, if you never get a chance to see Birth of a Nation and its promotion of racism and the Ku Klux Klan, you may be intellectually poorer, but your soul will be so much cleaner.)

It helps to keep the ballet model in mind when considering silent film. Movies developed together with the music that accompanied them, and we would appreciate them more if we saw them that way.

Of course, the basic level of appreciation is the story being told, and most movie-goers even in those early years, were there for the plot. Good over evil; love conquers all; the hero saves the maiden.

But we, watching now, should notice not just that surface level, but also how the movie was made: How the director uses a moving camera to advance the story; how the lighting underlines the mood of a scene; how the editing manages to keep us up-to-speed on parallel plot points, back and forth; how the close-up lets us into the mind of the actor.

And so, watching a silent film should be more like watching the dance. It is a different art form from sound film, and one that needs to be understood in its own way. The story drives the action in Swan Lake too, but we watch for the dancing and choreography.

I have a list of 10 silent films that demonstrate what the silent film can do. Recent film restorations have improved image quality, when a print can be struck from the original studio negative, and with restored musical scores, either from original sources, or new scores written in period style.

We’ll go from the easiest to understand and love to more adventurous films. In my experience, one of the best places to start is Buster Keaton’s Civil War film, The General.

The General

Keaton’s 1926 story is easy to follow, as Southern railroad engineer Johnny Gray spends most of the movie chasing a locomotive stolen by Yankee forces and then being chased by them. There are plenty of gags — Keaton was a genius with those — but also a comprehensible plot, easy to follow, and believable. Keaton’s direction is always clear, and with many exceptionally beautiful or intricate shots. The most expensive special effect shot of its time was later copied for The Bridge on the River Kwai, as Keaton has a train crashing off a burning bridge, followed by a dam breaking and a flood washing soldiers downriver. It’s a great film and for a wide audience. One of the great films of all times, silent or sound.

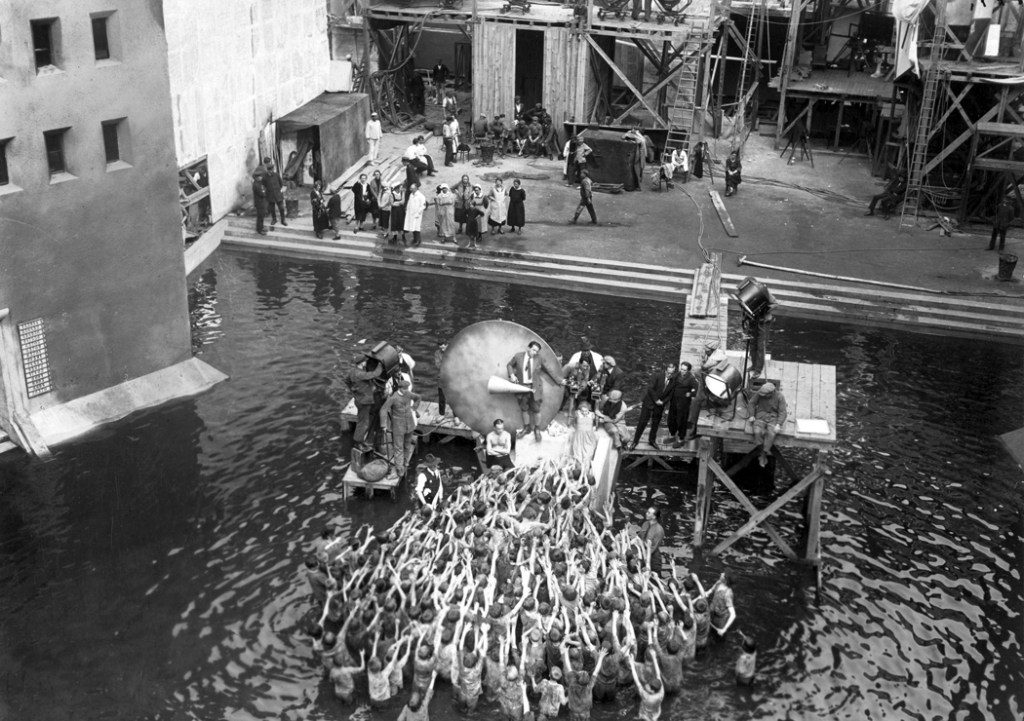

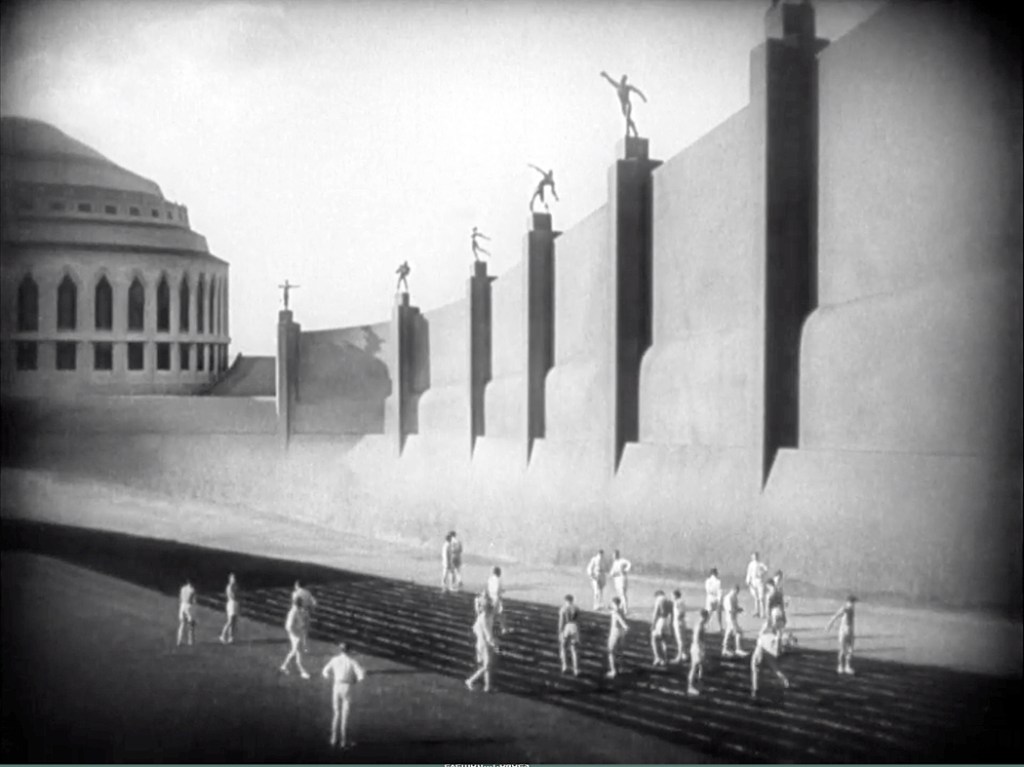

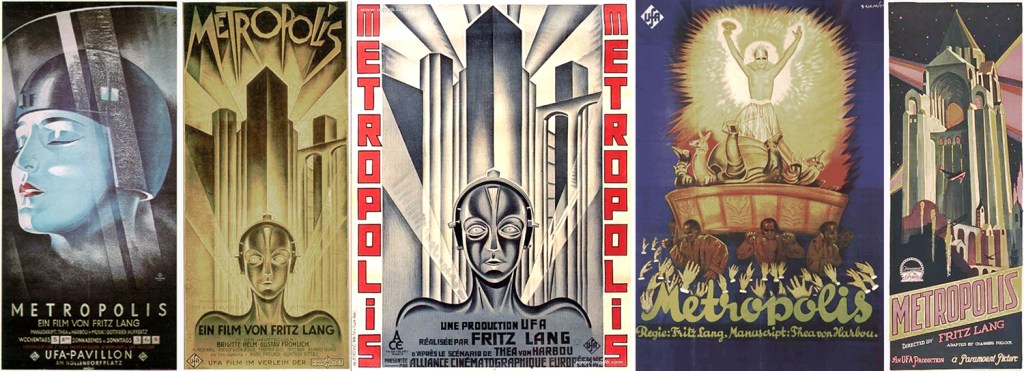

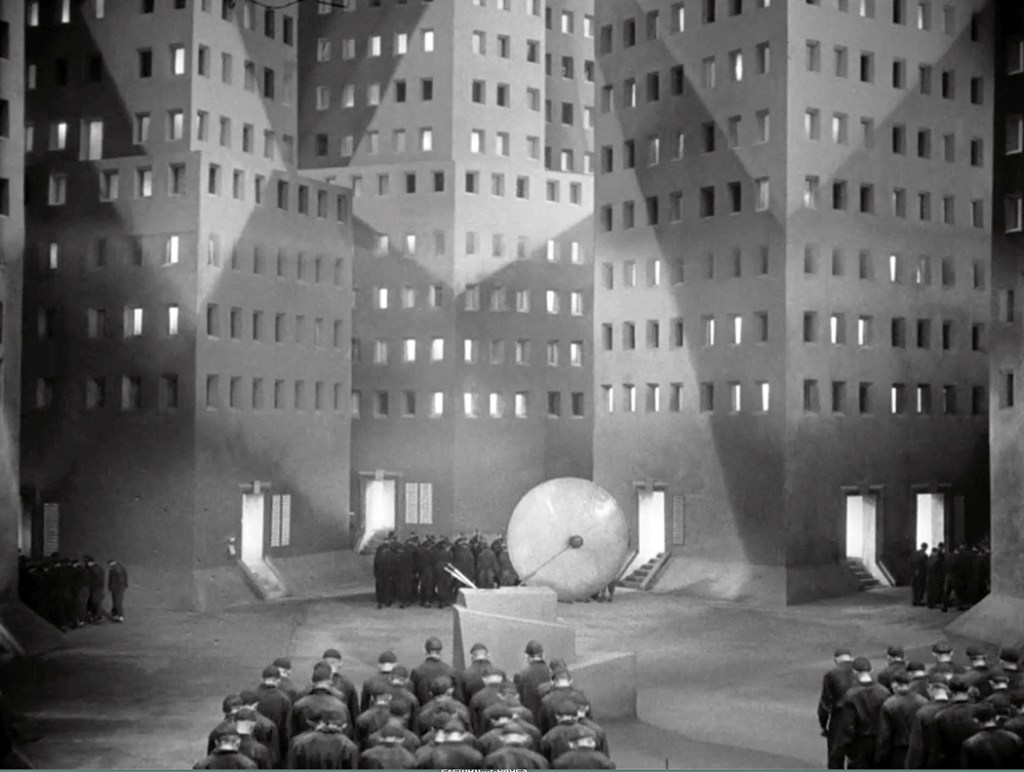

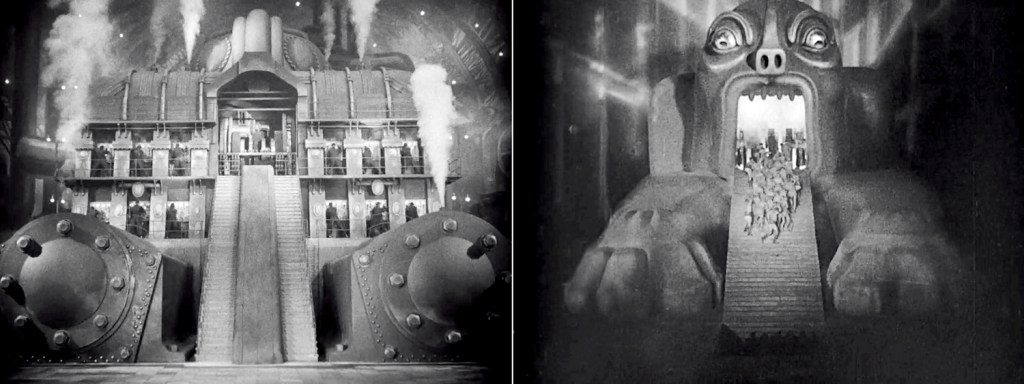

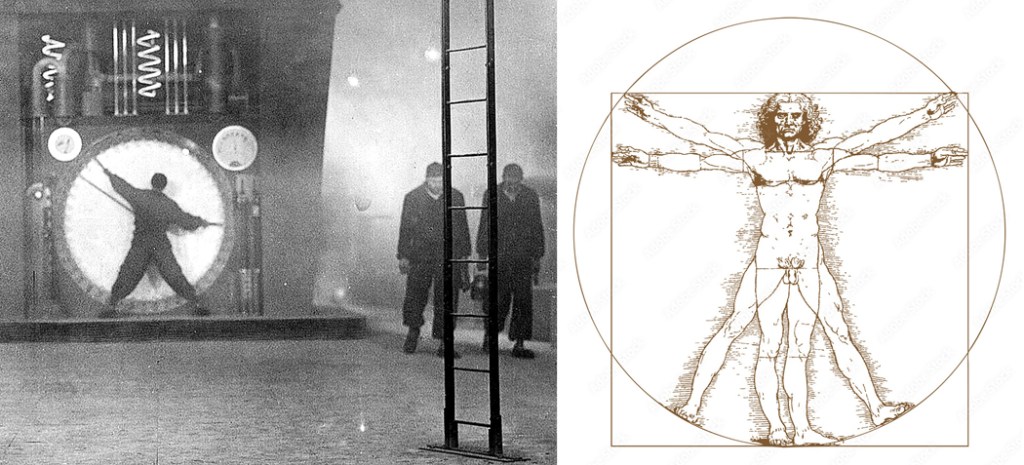

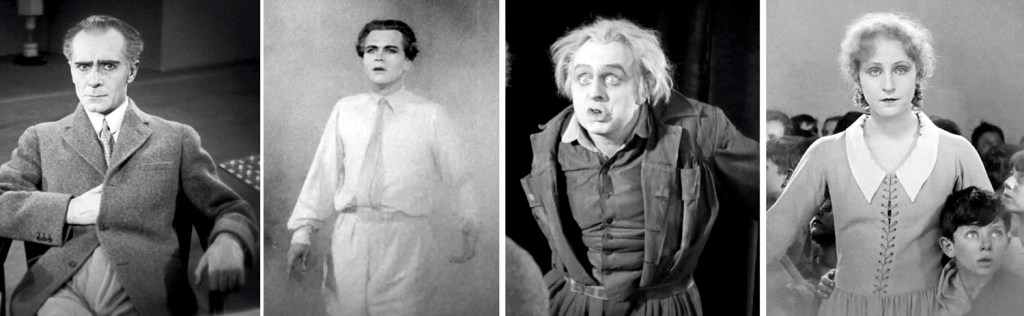

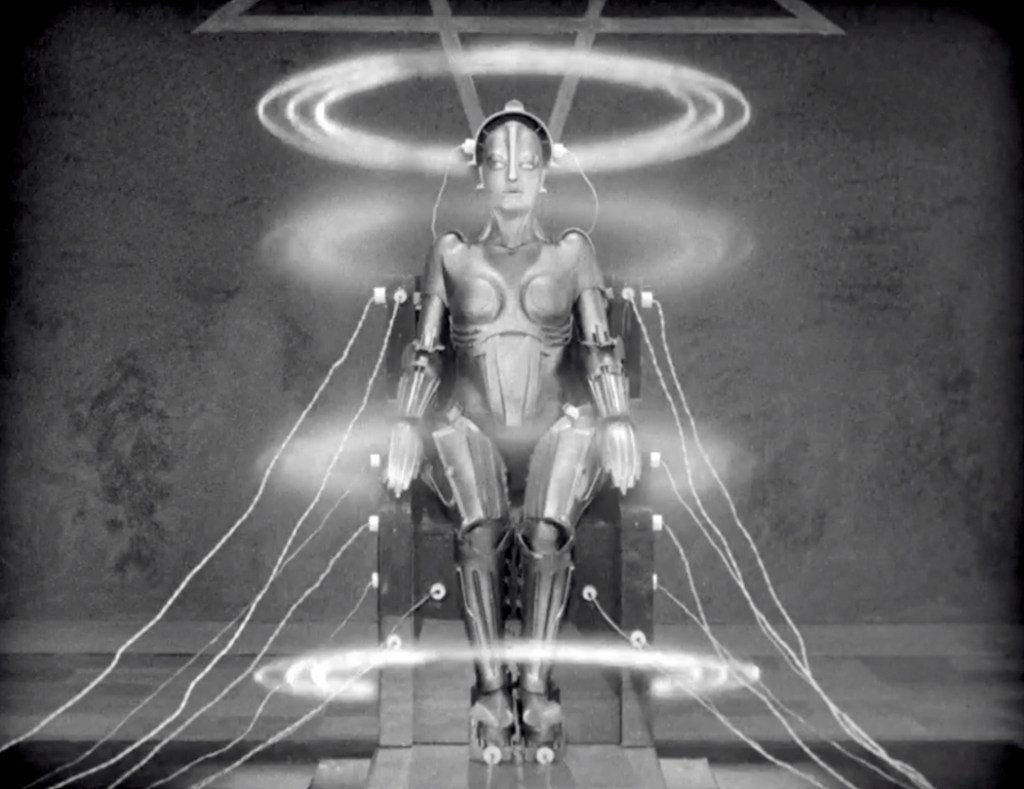

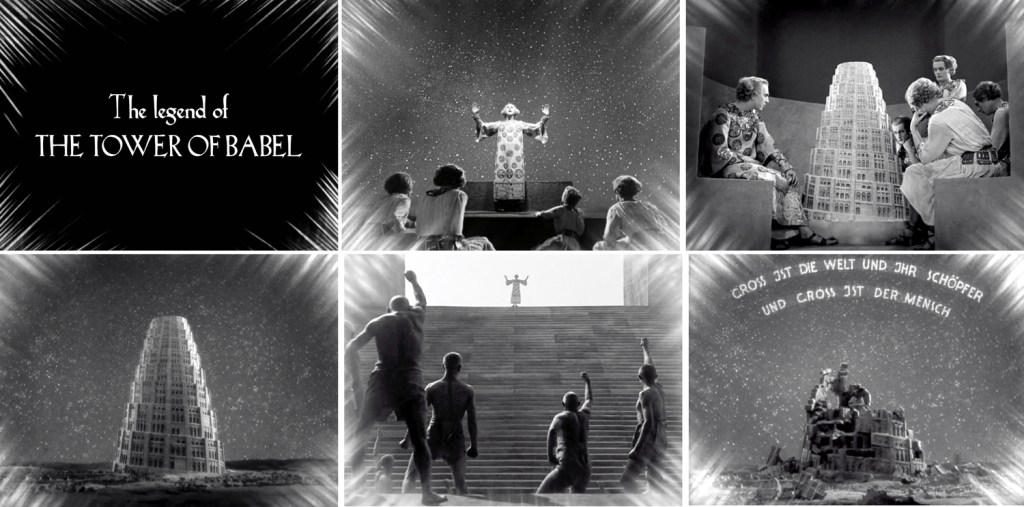

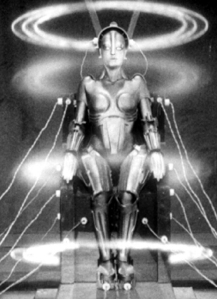

Metropolis

Fritz Lang’s 1926 sci-fi masterpiece has benefitted more than most from restoration. Seen previously in shortened versions, a new version has most of the missing footage returned so that story begins to make sense (even at its best, the plot never really made much sense). But it has some of the most stunning visuals ever put in front of a camera. It is a glorious film to watch, even if the acting sometimes seems maybe a smidge over the top. Despite that, it is also one of the greatest films of all time, and one of the most influential.

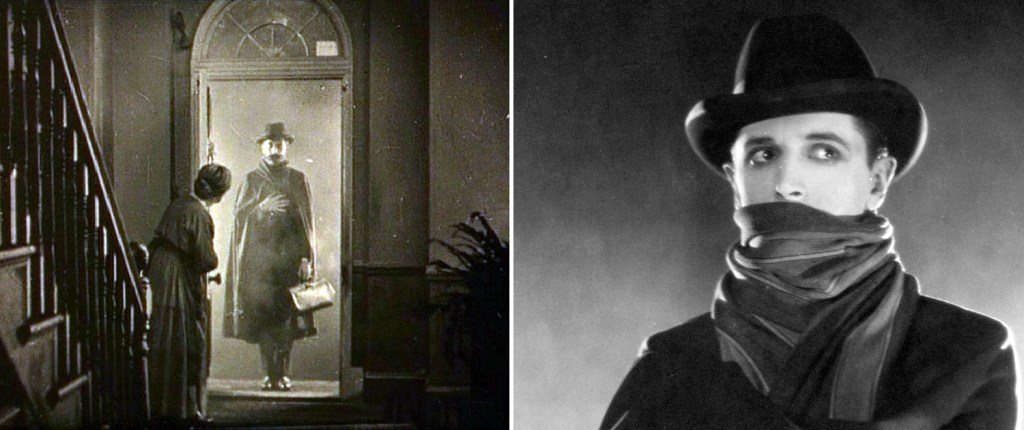

The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog

This 1927 Alfred Hitchcock thriller is a masterpiece of visual storytelling. Called the “first true Hitchcock film,” it plays with the fear raised by a Jack-the-Ripper style murderer in London and a mysterious lodger in a boarding house who may or may not be the killer. The film is chock full of Hitchcockian ticks, including a “wrong-man” plot, the obsession with blondes, and the plot-twist ending.

These three films offer little problem to the modern viewer and can be seen with little forgiveness needed for their lack of spoken dialog.

——————————

The next three are milestones in technical experimentation and the invention of cinematic conventions that are in common use today

Battleship Potemkin

In 1925, Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein told a story of the aborted 1905 rebellion through a version of the mutiny aboard the Russian battleship Potemkin. The film uses editing as fast as an MTV video to further the story, and inventing the montage. The section called “The Odessa Steps” still carries as much punch as anything ever made.

Napoleon

French filmmaker Abel Gance intended to make six films covering the life of Napoleon, but only finished the first. But it is five and a half hours long and uses many experimental techniques, putting his camera on a swing, or on the back of a galloping horse.

And in its climax, using three cameras and three movie screens to make a precursor version of Cinerama — huge widescreen images. It is an astonishing film for 1927.

The Passion of Joan of Arc

It sometimes seems as if Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 The Passion of Joan of Arc is entirely made up of close-ups of lead actress Maria Falconetti’s anguished face. But if proof was ever needed of the power of human expression, this movie is Exhibit A. It is emotionally overwhelming.

——————————

The next three films are documentaries, made before documentary film became hamstrung by an inflexible puritan ethic (fooey on you, Frederick Wiseman). Some use recreations and re-enactments, but give us real information nonetheless.

Häxan

Häxan, from 1925, is a Swedish film that investigates the phenomenon of witchcraft through the ages. It was banned or censored in many places for its anticlericism, nudity, and depictions of depravity, but ultimately comes down on the side of modern understandings of schizophrenia, hallucination and bigotry to explain the witch stories. It is mostly filmed recreations by actors, but tells a real story.

Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life

From 1925, the story of Grass’s creation is as breathtaking as the story it tells of the annual migration of 50,000 of Iran’s Bakhtiari people across the vast Zagros mountain range with their cattle. Stunning landscapes and death-defying river crossings, all captured on film by Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack, and Marguerite Harrison (Cooper and Schoedsack later made King Kong). The filmmakers took the migration along with the tribespeople, and suffered all they did along with them. This is one of my favorite films of all time.

Nanook of the North

Three years earlier, Robert Flaherty made what many consider the first film documentary, when he took his camera to northern Canada to film the lives of Inuk native, Nanook (“The Great Bear”) and his family.

It shows us how they lived and how they survived. Purists now complain that some of the shots were staged and that Nanook was an “actor” (although he was a genuine Inuk native. But the ideas of documentary right-mindedness didn’t exist in 1922, and there is a genuineness in Flaherty’s film that many more virtuous documentaries cannot equal.

——————————

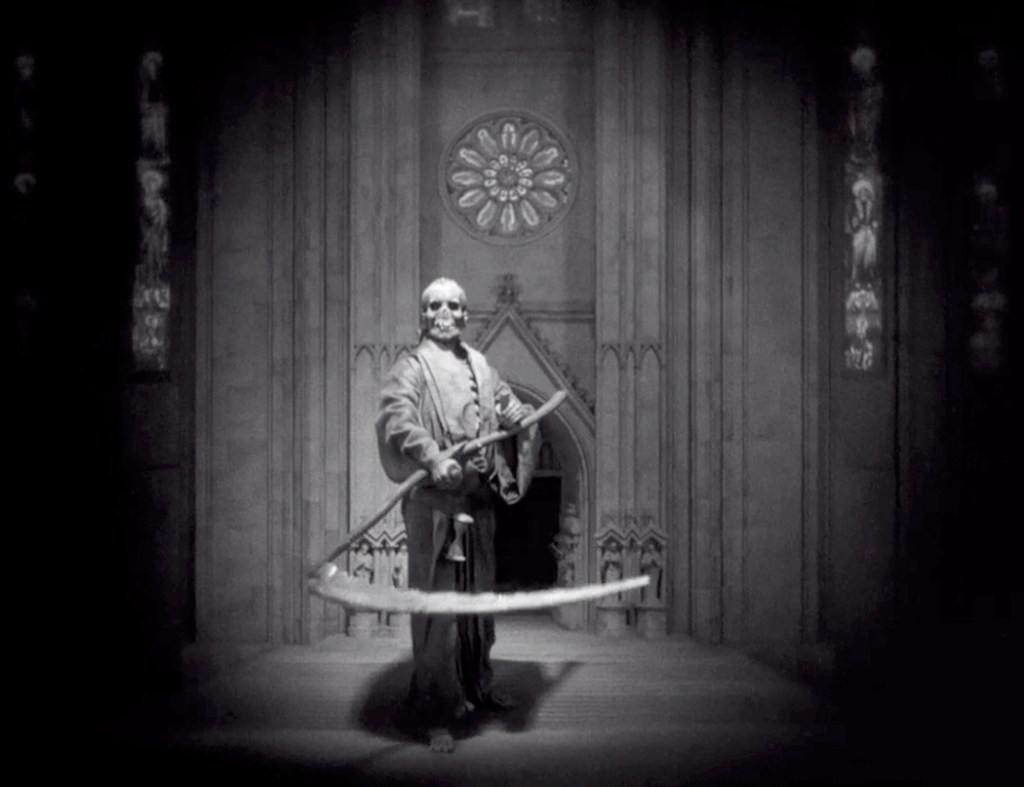

Number 10 on my list is actually a group of films. One thing that silent film did immeasurably well is horror. German filmmakers in the 1920s were immersed in an Expressionistic milieu that gave us films such as Nosferatu, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and The Golem and How He Came into the World. But Germany wasn’t the only place that worked out the magic of film images of the supernatural and spooky. Hollywood had its share, also.

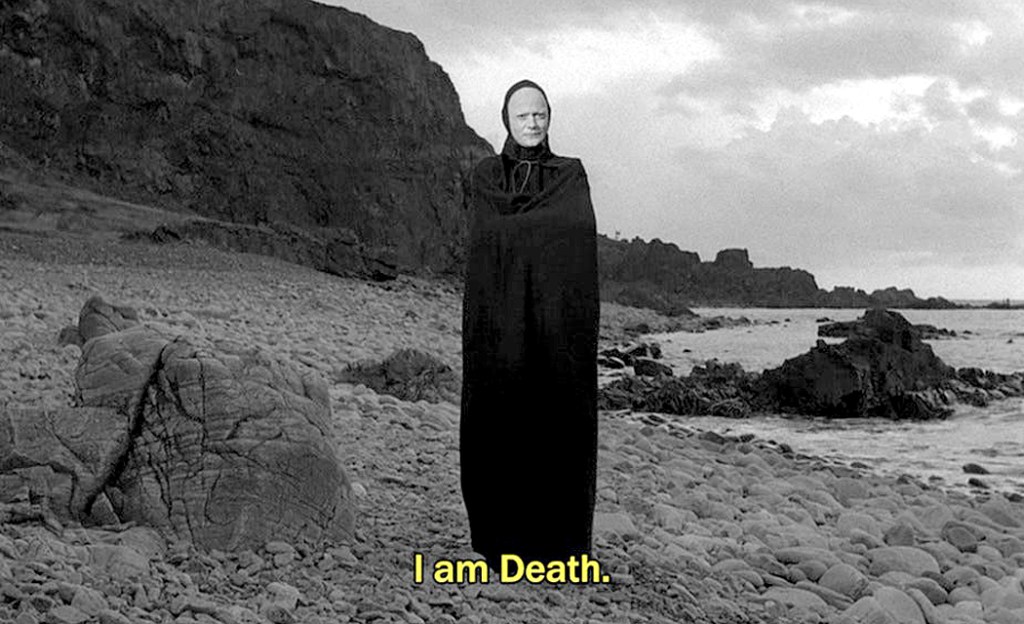

Nosferatu

F.W. Murnau’s plagiarized version of Bram Stoker’s Dracula nearly was lost to history. Stoker’s estate sued over the film, which Murnau had not secured the rights to, and the court decided all copies of Nosferatu should be destroyed. Luckily, a copy survived and is now seen as one of the true masterpieces of silent film. All shadows and sharp angles, gothic castles and claw-like hands, it is a much spookier version of the story than 1931’s sound version with Bela Lugosi.

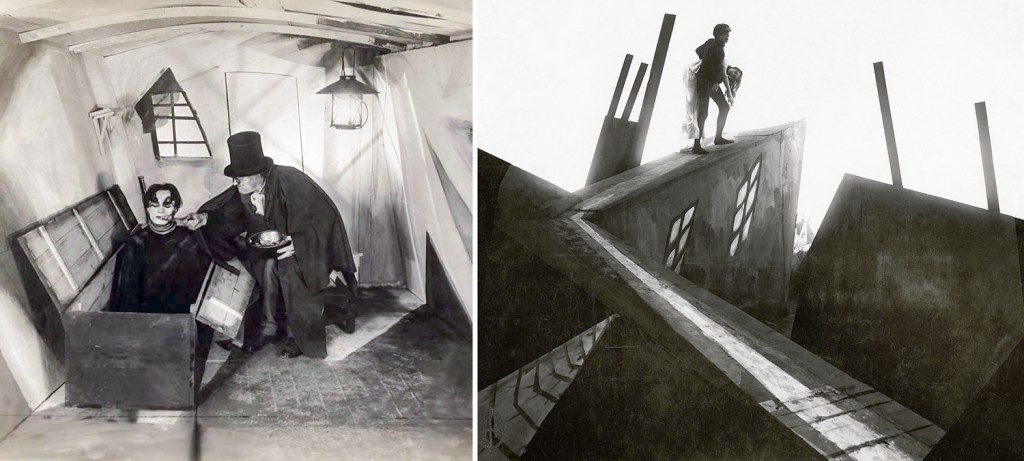

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

With its Expressionist cityscapes, with nary a right angle to be seen, and with Conrad Veidt’s pasty-faced somnambulist, the film is an absolute feast of visual inventiveness. If you ever needed a picture of what insanity might look like from the inside, this film is it.

The Phantom of the Opera

All of the films I have discussed here are among the best made in the silent era. Phantom of the Opera, if seen merely as the result of film direction and writing, is rather ordinary. But its visuals are unforgettable. Lon Chaney’s skull-like make-up for the phantom, the Gothic underworld of the Paris Opera, and perhaps most of all, the Two-Strip Technicolor episode where the phantom descends the grand staircase of the opera house wearing the costume of the Mask of Red Death.

Visually stunning, if less than brilliantly told, the Phantom of the Opera is buried in the consciousness of its audiences. I doubt that the several remakes of the film or the eponymous musical would have ever existed if the original film hadn’t been so compelling.

This hasn’t been my list of the Top 10 (or 12) silent films. Such a list would have to include Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans; Greed; City Lights; The Big Parade; Pandora’s Box; The Last Laugh; Flesh and the Devil; Cabiria — and a host of other contenders. Nor are these just my favorite films. I have others among the silents, including The Lost World or Hell’s Hinges.

Nor have I listed any of the many silent short comedies — especially missing: the films of Chaplin, Arbuckle, Lloyd, Keaton, the Keystone Cops or Laurel and Hardy. They are familiar enough and require no special pleading from me.

But I have hoped to make the case for an entire era of cinema, and that it is its own artform, and not merely film manqué, waiting quietly to be perfected by Al Jolson.

Click on any image to enlarge