My brother-in-law, Mel Steele, is a painter whose work I not only admire, but truly enjoy. They give my eyes great pleasure.

We visit Mel and his wife, Deborah, a few times each year and usually I bring along a big bag of DVDs, mostly art or foreign films. Mel and I share a common taste for such things.

Indeed, our tastes match up surprisingly well, not only in movies, but in music and art as well. We love the more difficult music, like Bartok quartets or 20th century operas, and for all that we get along admirably.

But there is a sticking point, a point of contention that we have never been able to resolve. There is a movie he hates and I love; and one I cannot stand that he adores. And I see no way of settling the dispute.

Mel grew up in Madison, N.C., in the 1940s and ’50s and only a block from his house was the local movie theater. He and his sister went to the movies at least once a week growing up. They saw all the usual Hollywood offerings, with Burt Lancaster, Greer Garson, Veronica Lake, Dorothy Lamour, Kirk Douglas — you get the picture.

I am a few years younger than Mel and since there was no movie house where I grew up, my film education came via television — old movies packaged by studios for rebroadcast on fledgling TV channels, such as WOR-TV from New York and its Million Dollar Movie. I was fed a lot of films from the 1930s, and, of course, all those marvelous-awful sci-fi films made for a pittance with Richard Carlson or Sonny Tufts.

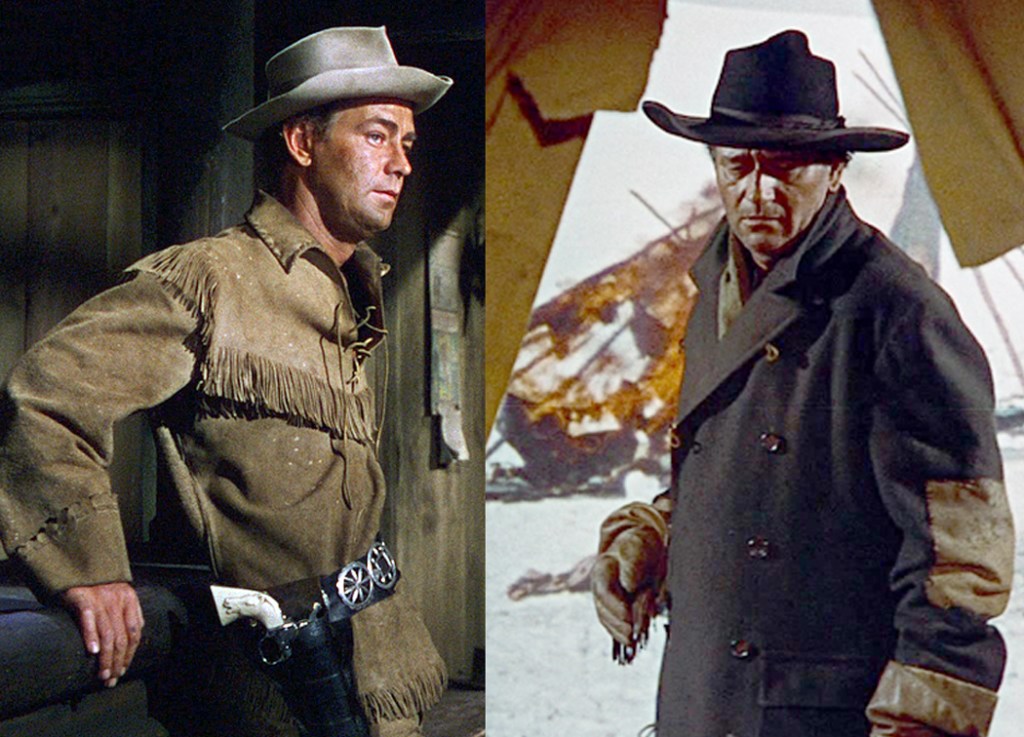

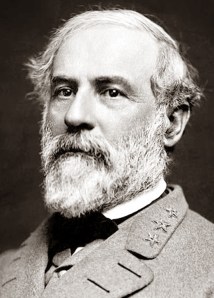

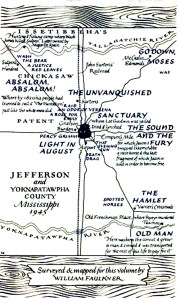

I don’t know if our different childhoods made the difference, or what, but that sticking point revolves around the best Western (not the motel chain). I mentioned once that I love The Searchers from 1956, a film in which John Wayne shows that he can actually act. It is a tough film, in which Wayne is an unsympathetic character, a bigot returned from the Civil War, having fought for the Confederacy. For my money, it is the best Western ever made, highlighting the shadings of culture clash and personality.

“Can’t stand the thing,” says Mel. “Can’t stand John Wayne.”

Indeed, it seems as if the presence of Wayne is the primary objection Mel has to the film. And I suspect that Mel’s dislike of Wayne has more to do with Wayne’s later right-wing politics — and the number of undistinguished star vehicles he made as an ever-paunchier alpha male — than with Wayne’s actual performance in The Searchers.

It is clear that Wayne didn’t always have to act, and could rely on nothing more than his screen persona in lesser films, such as North to Alaska, The Comancheros, McLintock!, Hatari, or The War Wagon. He seemed always to be playing a caricature of himself.

And then, there are those absolutely embarrassing moments in The Alamo or The Green Berets. Wayne’s shallow jingoism does not wear well. Nor does his support of the Vietnam War or Richard Nixon.

I used to share Mel’s disdain for John Wayne. The actor was pretty much a punchline. Really? Genghis Khan in The Conqueror? Gimme a break.

I first became acquainted with Wayne when I was a little kid, watching ancient Westerns on TV, where he was Stony Brook in the Three Mesquiteers films, or as “Singing Sandy” in a bunch of old Republic or Monogram Westerns. Compared with some of the old cowboys, Wayne had a graceful presence on screen, if no great acting chops.

Only as an adult, did I come across films in which Wayne played a character not merely himself. After seeing Howard Hawks’ Red River, director John Ford famously said, “Who knew the big lug could actually act?” Well, he could, even if he didn’t always feel the need to.

Then there are such films as The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, where he convincingly played a part 20 years older than he was at the time. And most of all, perhaps, his role as John Books in The Shootist, his final film, in when he seems to want to prove once and for all he can be an actor and not just a star.

Mel, of course, was having none of it. “Can’t stand the guy.”

In contrast, Mel proclaimed that the greatest Western ever is Shane, a movie I cannot abide. For me, it is the epitome of Hollywood phoniness. It is pure artifice, with not a believable moment in it.

Even its widescreen projection on release was fake: Paramount wanted something to compete with the then-new Cinemascope and Panavision — both anamorphic widescreen formats — and so they cropped the original Academy Ratio Shane at top and bottom to make a phony widescreen version.

“But it’s so beautiful,” Mel says. “Look at that landscape.” Yeah, I feel, a rip-off of Ansel Adams, with the Teton Mountains prominent in the background. It seems so self-consciously meaningful, so arty, so pretentiously “mythic,” that I cannot take it seriously. There is not a second in it that feels real — apart from the acting of Jean Arthur, who is the only fully human character in the film. These are not people but ideas moving around in the plot, as if they each wore a sign telling us what they signify. Again, only Arthur feels like a real person.

Allegory, for me, is always a tough sell.

I’ve never been able to warm to Alan Ladd. He is one of those movie stars from that era of Hollywood movie in which the dying studios made turkey after turkey.

Van Heflin always feels to me like someone the studios felt they could turn into a major star, but never managed to.

And Brandon deWilde is a blank-faced homunculus, as if that look of animal stupidity should be taken as the face of innocence. Actually the kid gives me the creeps.

The Searchers, in contrast, is filled with all the great character actors that John Ford used over and over. They are people, not cardboard cutouts.

Perhaps I have overstated my case. There are other great Westerns that may be as good as The Searchers. Ford probably made them. Modern Westerns tend to be more period-aware and historically better informed. And perhaps Shane isn’t the worst Western. There are plenty of hack Westerns with much less ambition than George Stevens brought to his work.

But the fact is, the comic disagreement Mel and I had was about these two films in particular. I was not able to persuade him; he was not able to persuade me. Let’s leave it at that.