David Attenborough on Desert Island Discs with host Kirsty Young in 2012

One of the longest running radio shows is Desert Island Discs, which has been on the BBC since 1942. It is often said to be the second longest-running radio show after the Grand Ole Opry, which cranked up in 1925, although a few critics have discovered some obscure programs in foreign climes that may have been on longer, and there’s also the British Shipping Forecast which began in 1861, before radio was even invented, and first disseminated via telegraph before switching to radio in 1924.

On Desert Island Discs, prominent people, whether politicians, entertainers, sports stars or academics, are asked to choose eight recordings they would take with them to the proverbial desert island, and place them in the context of their lives. Since the 1950s, they have also been asked to name a book, other than the Bible or Shakespeare, they would also take, and later still, adding on a “luxury item” they couldn’t live without.

Nearly 4,000 episodes have been broadcast, with some predictable results. The music most often mentioned is Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and the luxury item most chosen is pen and paper, or “writing materials,” although Tom Hanks specifically mentioned “a Hermes 3000 manual typewriter and paper.”

Many of the archived broadcasts can be heard from various online sources, and you can learn, for instance, that Alfred Hitchcock’s book choice was Mrs. Beeton’s Household Management, and his luxury item was “a continental railway timetable.” Some of the choices were equally eccentric. Oliver Reed wanted Winnie-the-Pooh to read and “an inflatable rubber woman.” Actress Janet Suzman wanted a “mink-lined hammock,” and Hugh Laurie asked for an encyclopedia and “a double set of throwing knives.” His long-time double-act partner Stephen Fry wanted a PG Wodehouse anthology and a “suicide pill.”

My favorite, so far, is John Cleese, who asked for Vincent Price’s cookery book and “a life-size statue of Margaret Thatcher and a baseball bat.”

One of the inevitable by-products of such a format is the urge to create your own list. And so, I have my own.

I grew up in New Jersey in a family largely indifferent to music. What music there was came on TV in such variety shows as Perry Como or Dinah Shore. When I was little, there was a small portable record-player on which I played children’s songs, but I don’t count any of that. “Fire, fire, fire, raging all about. Here come the firemen to put the fire out.”

My musical education began in high school when my first serious girlfriend played music on the phonograph while we spooned on the sofa in her parents’ house. She went on to become a professional bassoonist and was studying at the time with Loren Glickman, who played the difficult opening bassoon solo on Igor Stravinsky’s recording of his Rite of Spring. I hadn’t known such music existed. It was mesmerizing. Who knew it was great make-out music? And so, that is my first choice for my desert island disc.

There have been hundreds of other recordings of that music, and a few, perhaps, more exciting or primitive than the composer’s own, but that recording has never been out of print and comes in many versions, from LP to 8-Track to CD and now, streaming. As an introduction to classical music, I could hardly have done better — dive into the deep end.

When I got to college in North Carolina, I made the acquaintance of Alexander Barker, who has remained my best friend for 60 years. He was as enthusiastic about classical music as I was and we spent hours in our dorm rooms spinning LPs and introducing each other to music that was our favorites. We were, of course, very serious about great music, as only college students can be, but we knew Beethoven’s string quartets were as serious as you could get. I bought a budget-line set of the quartets, by the Fine Arts Quartet on the off-brand Murray Hill label, and one evening, we started with Opus 18, No. 1 and played through all 16 of them, plus the Grosse Fuge, in one marathon session. (We later attempted the same thing with the piano sonatas, but gave up in exhaustion and the need for sleep by the time we hit the Hammerklavier.)

I have not been able to find a CD version of the Fine Arts Quartet set, but I found much better-played versions later on. I have owned a half-dozen or so complete sets of the Beethoven quartets, and as many of just the late quartets, but on the desert island, I would take the original mono versions by the Budapest String Quartet. They redid them later in stereo, but I like the earlier set better. I could have chosen the Guarneri, or the Tokyo or the Emerson, but I still think the Budapest have the measure of them best.

If you have the earnest seriousness of youth, you will eventually get into Wagner. After college and after a failed first marriage, I was living in North Carolina with my favorite redhead, scratching by on subsistence jobs, and I managed to save enough money to finally buy the Solti Ring. Something like 16 hours of music subsuming four operas, it opened up a world of myth and raw musical power. Now in retirement, I own five Ring cycles on CD and another two on DVD. And I’ve attended two complete live Ring cycles (not a patch on my late friend Dimitri Drobatschewsky, who went to Bayreuth 16 times beginning just after World War II.) But the Solti Ring of the Nibelungs is still my go-to set. And with it, I must also take the Deryck Cooke explication of the cycle, An Introduction to “Der Ring des Nibelungen.” Can’t have one without the other; they’re a set.

When the redhead and I split up, after seven years, I moved to Seattle and began working at the zoo, where I met a zookeeper whose hair was as blond as the sun. I fell. She had been a professional swing dancer at one time, and she played me old swing records on her Wurlitzer jukebox, which she had at her home. I had a whole new universe of music to learn about. But the one who stuck was the jazz musician closest to writing classical music, Duke Ellington.

I still have about 50 CDs of Ellington’s recordings. There are counted several epochs of Ellington’s career, beginning with the “jungle music” of the 1920s and going through his rebirth at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1956. But most count the high point of his band and music to be those years in the early 1940s when Ben Webster was his tenor sax man and Jimmie Blanton was his string bass player. A collection of their recordings has been issued several times as “The Blanton-Webster Band.” It was the era of Take the A Train, Ko-Ko, Harlem Airshaft, and Perdido.

But then, neither can I do without The Queen’s Suite, which he wrote with Billy Strayhorn in 1971, and is his most completely classically composed work. I love it. And so, I’m adding it to my Ellington entry.

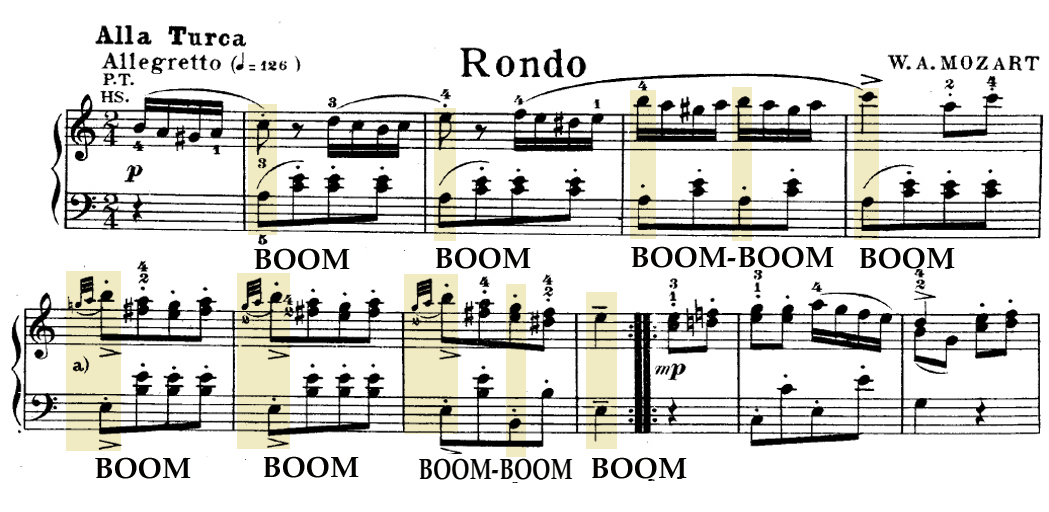

The zookeeper dumped me and I moved back to North Carolina. A few years later, I met Carole, who I married and lived with for 35 years, until her death in 2017. Marriage humanized me, and the most human composer is Mozart and the most humanistic of conductors was Bruno Walter. It was the the last years of the LP era, in 1980, and before digital took over, I found the last six symphonies of Mozart played by Walter and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra (a pickup ensemble, mostly of musicians from the New York Philharmonic).

Walter’s Mozart remains the most humane and beautiful version of these works, which are now buried under historical-performance rhetoric and bounce along at a jog-trot, mechanistic pace. But one can still find the echt-Mozart, songful, emotional, and velvety rich, under Walter’s baton. Like all of my choices for the desert island, it has never been out of print.

Carole and I moved to Arizona in 1987, where she took up teaching art to elementary pupils, and I began writing for The Arizona Republic as its art critic (later also its classical music critic).

When we moved to a house at the foot of Camelback Mountain, it was a 20 to 30 minute drive (depending on traffic) to the Republic office downtown, and I found the perfect drive-time music, playing a Haydn symphony each way. I eventually went through all 104 symphonies, driving back and forth, three times, and absorbed their spirit from the Austro-Hungarian Haydn Orchestra and Adam Fischer. They have become my go-to performers for this music. I also have the earlier Antal Dorati version, which sometimes sounds like a quick read-through, and later was sent a review copy of the Dennis Russel Davies versions on Sony, which proved to be the most utterly humorless Haydn possible and I had to give them away. How can anyone misunderstand this music so thoroughly?

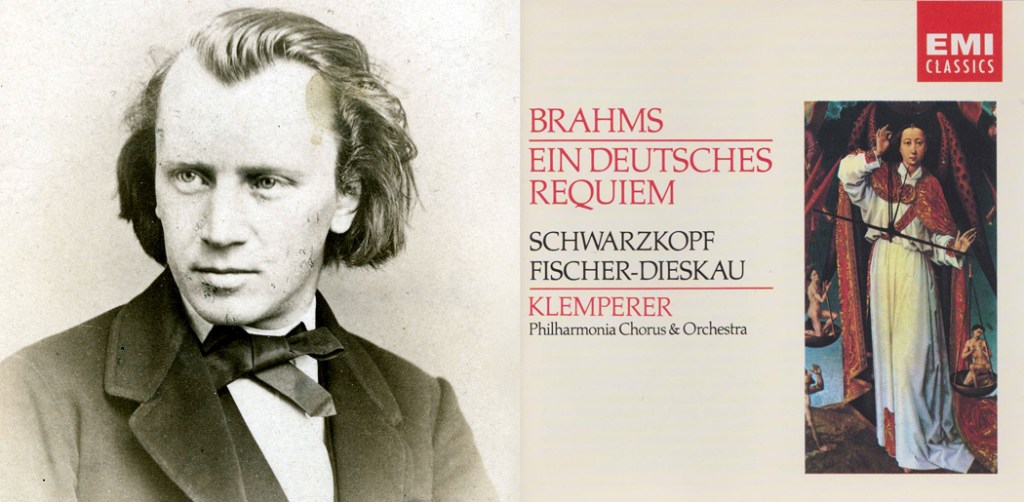

When Carole died, and I sunk into grief, from which I have never fully recovered, I found myself listening with my whole being to Brahms German Requiem. I have spent the anniversary of her death every year driving up the Blue Ridge Parkway to find an old fire road into the woods, and sit quietly to Bruno Walter’s recording of the German Requiem. It is the most sympathetic, consoling music ever written.

On Desert Island Discs, they also ask the guests to choose the one recording, above all, which they would take if everything else were not possible. And for me that is Johann Sebastian Bach’s Passion According to Saint Matthew, a three-hour musical retelling of the last days of Jesus and his death. I am not religious. (I am so not religious, I not even an atheist.) But every note of Bach’s music speaks to me on the deepest level of humanity. The opening chorus and the ending chorus are, for me, the greatest musical utterances ever penned. I’m keeping it with me.

There are many performances, and no one really does it badly, but most recordings now have been run through the historical performance wringer and the juice has been squeezed out. This is majestic and noble music, not something from a squeeze box. And the recording left behind by Otto Klemperer is the one I listen to over and over. He’s got the measure of this music.

That leaves us a book and a luxury. People value books for, usually, one of three reasons. Either for the information they gather, or for the stories that are told, or for the prose they are written in. I fall into the last camp. I thought about Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, which is an utter joy to read, whether you care about the factual history of Rome or not. I revel in its river of words. But I read it in short segments, ultimately filling up like a rich meal and need to wait some hours before hitting the table again. And, for all the wonderful writing, there is a sameness that can creep in.

Or I might have chosen a classic that somehow I’ve missed in 77 years of life. Many on Desert Island Discs have taken Marcel Proust’s Á la Recherche du Temps Perdu. But when it comes to monster works, I already put in my time, having gotten through The Gulag Archipelago. I no longer need to prove myself.

So, I have chosen Joyce’s Ulysses, the book I can read and re-read over and over, with such a variety of prose and method and such delicious words, that I don’t think I could ever tire of it.

As for a luxury item, I had some difficulty coming up with something, because I am not much for luxury. But I have always owned a pear-wood handled Opinel folding knife. The current one sits in the glove compartment of the car, ready for anything called for. A man needs his tools.

Of course, the whole exercise is entirely pointless. There is no desert island, and with a house full of books, CDs, musical scores, and art, I don’t need to choose so parsimoniously. The whole idea is merely a pleasant game to play.

But going through the process, and forcing myself to narrow the list arbitrarily, I come to see myself in a dusty mirror. And I surprise myself, looking back at me.