Buddhism has its Noble Eightfold Path, and I have my list of Seven Noble Violin Concertos.

There are two basic varieties of concerto in the Western tradition. In one, the purpose is to be pleasing, either through beautiful and graceful melody or by entertaining the audience with the soloist’s virtuosity.

But the other path — what I’m calling the “noble concerto” is more symphonic in conception, where an estimable composer uses the concerto form to express some deep or profound feelings and the solo instrument is just a means to do so.

This is not to disparage the first type of concerto. Two of the greatest and most popular violin concertos fall into this group: the Mendelssohn concerto (certainly one of the most beautiful ever and perhaps the only one that could be called “perfect.”) and the Tchaikovsky, which, although it is difficult for the performer, cannot be said to plumb the emotional depths. Doesn’t mean it isn’t a great concerto, but its emotional qualities tend to be melodramatic rather than profound.

The concertos of Paganini are tuneful, also, but mainly exist to show off his digital gymnastics. The concertos of Vieuxtemps, Viotti, and Wieniawski are all adequate but shallow works. Don’t get me started on Ludwig Spohr. Even Mozart’s concertos for violin are more pleasing than profound. It’s all they were ever meant to be, and we shouldn’t ask for them to be more.

Some of these concertos are among my favorites. Beyond the Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky, I adore the Korngold, the Barber, both Prokofievs and the Stravinsky. I even love both Philip Glass goes at the genre (has he written a third while I wasn’t looking?) I listen to all of them over and over, with great pleasure and satisfaction. So I am not writing them off simply because they don’t make my list of noble concertos.

The noble concerto doesn’t seek to ingratiate itself. It is not written with the audience in mind, but rather to express the thoughts and emotions common to humanity. They bear a seriousness of purpose. They may seem more austere, less immediately appealing, but in the long run, they reward a lifetime of listening, and in multiple interpretations. You learn about yourself by listening to them.

I am not including concertos earlier than Beethoven, which means, no Bach, no Vivaldi, Tartini, Locatelli or Corelli. In their day, “noble” simply meant a spot in the social hierarchy, a position of privilege unearned but born into. Beethoven changed that, claiming a place for an earned nobility of purpose and ability.

“Prince,” he told his patron, Prince Lichnowsky, “what you are, you are through chance and birth; what I am, I am through my own labor. There are many princes and there will continue to be thousands more, but there is only one Beethoven.” Which would sound like boasting, if he didn’t have the walk to back up the talk.

Nobility of the kind Beethoven meant was defined in Samuel Johnson’s dictionary as, “a scorn of meanness,” or low intention and an embrace of moral and ethical excellence and personal integrity.

I call these seven concertos “noble,” but that is a word well out of fashion these days, when anything elevated, whether nobility or heroism or honor, is suspect. The facile use of such words by fascists and totalitarians have made them stink to the mind. Yet, the truths of them are still there, and can be found in words, actions, art and literature. And in these seven concertos.

It’s not that I want to listen to these seven to the exclusion of the others. They each have their place, their purpose and their virtues. But these seven are just more, what — serious. They make more demands on the listener, and provide greater rewards for the effort. A seriousness of purpose.

—Let’s take them in historical order, beginning with the obvious first choice, the Beethoven Violin Concerto in D, op. 61, from 1806.

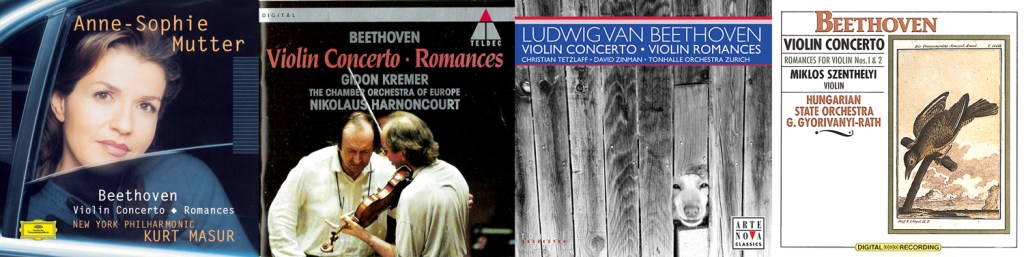

At one time, I owned more than 40 recordings of the Beethoven concerto, which I listened to and studied with the score, and so, I am quite familiar with most of these CDs. I got rid of almost all of them when I moved from Arizona to North Carolina, along with three-quarters of all my classical music collection (now, I’m reduced to little more than 2500 CDs. Weep for me.)

There have been more than a hundred notable recordings of the Beethoven concerto, from the time of acoustic recording to our streaming present.

I count five distinct ages of recorded music. The first from the era of the 78 rpm record, where concertos and symphonies had to be spread out onto many discs, with odd breaks in between. This was an age of giants, of Fritz Kreisler, Mischa Elman, of Bronislaw Huberman, Albert Sammons, Efrem Zimbalist, Adolf Busch, and, crossing over eras, Jascha Heifetz.

The second era was that of the LP, both mono and stereo. This was the golden age of classical music recordings, where established stars of an earlier age got to show off their stuff in hi-fidelity, and newer star performers made their names.

This was followed by the digital era, beginning in the 1980s, with the introduction of CDs. A few conductors and orchestras dominated the market — Herbert von Karajan re-recorded everything he had previously done in 78s and on LPs, and not always to the better.

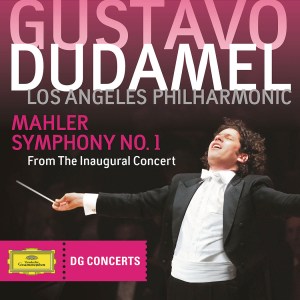

The new century has been marked by an entire new generation of soloists, better trained and technically more perfectly accomplished than most of the great old names, and they have made some astonishing recordings. What I sometimes suspect is that they lack the understanding and commitment to what the music means, intellectually. Facile and beautiful and technically perfect, but not always as deep.

And now, we live in an age that overlaps that, of historically informed performance, in which everything is played lighter, faster and punchier — and all the nobility is squeezed out as suspect and as fogeyism.

From the first era, we have two recordings by Kreisler, from 1926 with Leo Blech conducting and a second from 1936 under the baton of John Barbirolli. You might think the later recording was in better sound, but they are pretty equal in that way. Clearly they are old scratchy recordings, but the brilliance of Kreisler shines through anyway. In many ways, these are my favorite recordings of all. Kreisler has a warmth, a beauty of phrasing and a nobility that is exceptional.

There is also the Bronislaw Huberman with George Szell from 1934 in surprisingly good sound, and by Jascha Heifetz with Arturo Toscanini from 1940 that some prefer over his later LP one with Charles Munch.

From the second era, there were many great performances. Four I would never do without are my favorite in good sound, Yehudi Menuhin and Wilhelm Furtwangler from 1953; the second Heifetz recording, from 1955 with Munch; the one that is a consensus reference recording, Wolfgang Schneiderhan with Eugen Jochum, from 1962; and for utter beauty of tone, Zino Francescatti with Bruno Walter, from 1961.

Also, later in the LP era, some big names with some big sounds: Isaac Stern with Leonard Bernstein (1959); Itzhak Perlman with Carlo Maria Giulini (1981); Pinchas Zuckerman with Daniel Barenboim (1977); and Anne-Sophie Mutter with Karajan in her first recording of the work (1979). Any of these is a first rank performance in good sound, and define what the Beethoven Violin Concerto should be.

Among the younger violinists, there is plenty of good playing, but fewer deep dives. You still find the old grandeur with Hilary Hahn and David Zinman; and clean musicianship with Vadim Repin and Riccardo Muti; and Kyung Wha Chung and Simon Rattle; and Leonidas Kavakos conducting and playing.

All the famous fiddlers of the golden age made multiple recordings of the concerto, the Oistrakhs, the Milsteins, the Sterns, the Perlmans and Grumiauxs and Szeryngs. And mostly, they were consistent across performances, with different orchestras and conductors. But Anne-Sophie Mutter re-recorded the concerto with very different results. In 2002, she played it with Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic and gave us a complete re-interpretation of the concerto. Some loved it; some hated it; few were indifferent. I love it.

It is one of several outliers among interpretations. You can always count on Niklaus Harnoncourt (aka “the Wild Man of Borneo”) to be wayward, and his recording with Gidon Kremer is peculiar by including a piano in the first-movement cadenza. Why? Beethoven didn’t write a cadenza for his violin concerto, but he did write one for his piano transcription of the work, and Kremer used the piano version to reverse-engineer a version for violin, but left in a supporting piano (and tympani part). That still doesn’t answer a “why.”

Christian Tezlaff recorded a version with Zinman and the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich that, while on modern instruments, comes highly inflected by the original instrument ethos. It is beautiful in its way, but it is fast and zippy.

I also include a personal favorite with little circulation: A budget-label recording by the Hungarian violinist Miklos Szenthelyi. I saw him live and I’ve never seen anyone with such perfect posture or so fine a tone. I can’t recommend it for everyone (and it probably isn’t available anymore, anyway), but I have a soft spot in my heart for it.

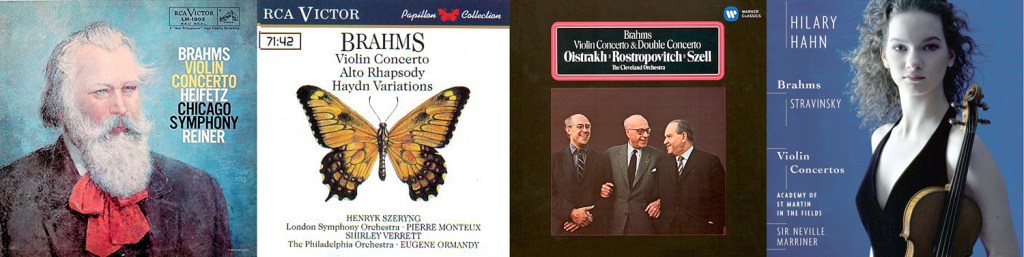

—The next big concerto comes some seven decades later with Brahms Violin Concerto in D, op. 77 from 1878. Brahms was clearly modeling his concerto and its mood on Beethoven’s. He wrote it for his friend, Joseph Joachim, who was also the violinist who popularized Beethoven’s concerto after years of neglect.

The Brahms concerto is more genial and has always been popular with audiences. There are as many recordings of it as there are of its predecessor, including a version by Fritz Kreisler that is still worth listening to, through the scratches and clicks of a recording made in 1936.

Of all of them, these are my favorites, that I listen to over and over, and from all the different eras of recording.

The Heifetz is quick, dead-on, energetic and exciting. He is sometimes thought of as cool and unemotional, but I think instead that it is white-hot. The Szeryng recording is the one I’ve had the longest and listen to the most — it’s my go-to recording, but that may just be that I’m so used to it, it has imprinted on my mind. The polar opposite of Heifetz is Oistrakh, which is rich and warm, with Szell providing the secure setting for the jewel violin. Of more recent recordings, Hilary Hahn is utterly gorgeous. It gives lie to the myth that only “historical” recordings are great.

—Chronologically, the next in line is Sibelius’ Violin Concerto in D-minor, op. 47 from 1905. If ever music required the ice of Heifetz, it is Sibelius’ concerto, which sounds like a blast from the Arctic. His recording, from 1959 is riveting. But so is the warmer version with Isaac Stern and Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra from 1969. We may forget what a stunning and brilliant violinist Stern was, if we only knew him from his later years, when his intonation went south. In Sibelius, he is one of the great ones.

Of the modern era, Perlman with Andre Previn, from 1979, has all of Perlman’s grand personality and character, with technical perfection. But the one I listen to most, and with total love, is by Anne-Sophie Mutter, also with Previn, from 1995.

I need to note, somewhere in this rundown, that the list of dependable fiddle stars are just that — dependable. If Mutter is my favorite here, that doesn’t mean that you aren’t getting the goods from Oistrakh, Vengerov, Hahn, Mullova, Bell, Chang, or Zuckerman. Whether it is Beethoven or Bartok, you will not likely be disappointed. I am here listing just my own favorites. My own taste.

—And my own taste runs strongly to the Elgar Violin Concerto in B-minor, op. 61 from 1910. This is a testament to my own growth and change. There was a time when I wouldn’t touch Elgar with a 10-foot phonograph stylus. I found him stuffy and boring. But that was because I hadn’t really heard much of his music. Then, I heard Steven Moeckel play it with the Phoenix Symphony and was swept away. I discussed the concerto with Moeckel and he advocated for it with devotion — indeed, it was his insistence that the the Phoenix Symphony tackle it that made the performance happen. (Moeckel also has a CD out with the Elgar violin sonata that makes a case for it, too.)

This is the longest concerto on my list, but also one that I have to listen to with complete attention from beginning to end. It speaks to me with a directness that I recognize. It is rich to overflowing and absolutely tears my heart out.

My go-to recording is also the oldest, by English violinist Alfred Sammons, made in 1929 with Henry Wood conducting. It has the greatest breadth and depth of any I have heard, in sound that is not as bad as its birth year would imply. A famous early recording was made with Yehudi Menuhin under the baton of the composer, that should show us how the composer meant it to go — if only Elgar were a better conductor.

The concerto kind of disappeared after that, until the young fiddler Kennedy (he went by only one name back then) came out with a best-selling version in 1984 with Vernon Handley and the London Phil. It is still Kennedy’s best recording (he went pop soon after).

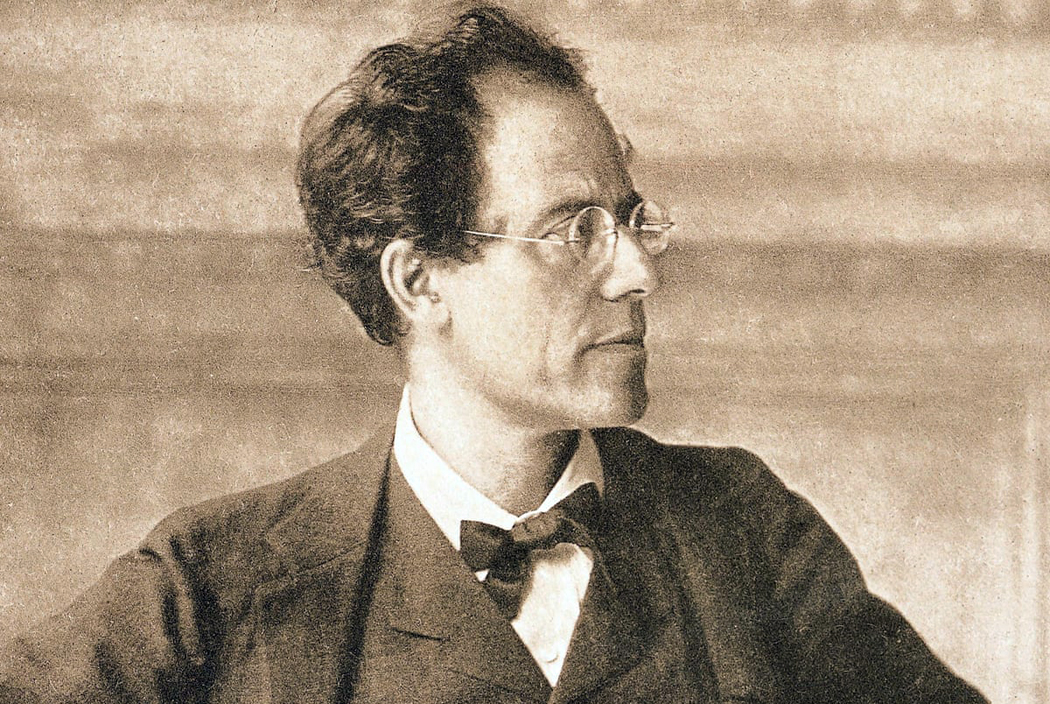

But my favorite remains Hilary Hahn and the London Symphony with Colin Davis. Rich, warm, and in truly modern sound, it breaks my heart every time.

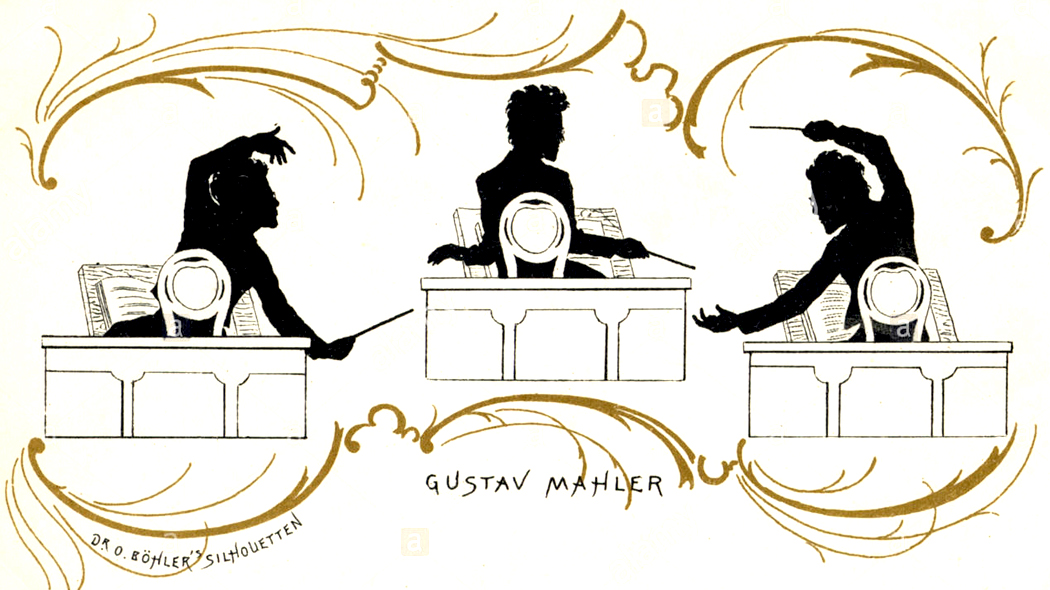

—Speaking of broken hearts, there is no more personal utterance than Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto from 1935. Subtitled, “To the memory of an angel,” it commemorates the death of 18-year-old Manon Gropius, daughter of Alma Mahler and Walter Gropius. It is also the most listener-friendly piece of 12-tone music ever written, as Berg managed to cross atonality with tonal music in a way so clever that doctoral dissertations are still being written about it.

In two movements, it is blood-curdling in parts, and soul-soothing in others. Every emotion in it seems authentic, and not conventional. It is one of those piece of music you cannot ever just put on in the background — you have to listen and you have to invest yourself in it completely.

It was commissioned by violinist Louis Krasner and we have a performance by him conducted by Berg’s colleague Anton Webern, from 1936, which should demonstrate the most bona fides, despite the poor sound quality.

I first learned the piece listening to Arthur Grumiaux and it is still one of my favorites. Yehudi Menuhin played it with Pierre Boulez, who brings his own authority to Second Vienna School music.

But the one I listen to now, over and over, is Mutter, with James Levine and the Chicago Symphony. This is serious music for the serious listener.

—At roughly the same time, Bela Bartok wrote his Violin Concerto No. 2, from 1938. In three movements, it was commissioned by Zoltan Szekely and first recorded by him with Willem Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra. It is a recording of the world premiere and has authority for that reason alone, other than that it’s a great performance, although hampered by horrible sound.

Much better sounding, and one of the great recordings, is by Menuhin and Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Philharmonia, from 1954. It has always been my reference recording. Good sound for the era and great performance.

Isaac Stern is also great, with Bernstein, and his performance is usually paired with Bartok’s lesser-known and seldom-performed first concerto, which is youthful and unashamedly beautiful.

And I wouldn’t be without Mutter’s version, with Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony.

—It would be hard to choose which is Dimitri Shostakovich’s best work, but my vote goes for his Violin Concerto No. 1, in A-minor, op. 99 from 1948, coincidentally, the year I was born. As personal as the Berg concerto, but with a powerful overlay of the political, and written under the oppression of Stalin, this is the most monumental violin concerto, probably, since Beethoven. When well-played (and it is difficult), it drains you of all the psychic energy you can muster.

It is the bottom line on all seven of these concertos that we are meant to listen to them with the same beginning-to-end concentration that we would spend on poetry or defusing a bomb. They are not “put it on while I do the dishes” music, but life-and-death music.

And that is what you get with David Oistrakh, who was the originator of the concerto and a friend of Shostakovich. He recorded it multiple times, but the first, with Dimitri Mitropoulos and the New York Phil, from 1956 is still the greatest one, the most committed. It is the one I listen to when I want to really dive deeply into what the music means, and come away shattered with the realization of all the horror of the 20th century.

Performances by Lydia Mordkovitch and Dmitry Sitkovetsky are in modern sound and also brilliant. Hahn is especially well-recorded, with Marek Janowski and the Oslo Philharmonic.

But the Oistrakh. If the concerto was personal to the composer, it was to the violinist, too. They both had known it all, seen it all, suffered it all.

And so, these seven concertos — seven sisters — seem a notch above the rest, in terms of seriousness and execution. You should have all of them in performances that express all the humanity that is packed into them. These are my suggestions; you may have your own.

Click on any image to enlarge