“Postmodernism” is a catchall word that seems to have lost all meaning, especially because it hardly seems “post-“ at all. In the popular mind — if it thinks about such art-historical buzzwords at all — it means paintings of “Donald Duck Crossing the Delaware,” a mashup of pop culture and the history of fine art.

But such things are hardly new. In fact, rejiggering the past has been a central tenet of Modernism for more than a century. Old wine in new bottles. It could be argued that remaking the old is central to all art for as long as it has existed. Virgil remade Homer and Milton remade them both, and Derek Walcott’s Omeros does it all over again. And even the Iliad is the result of its previous oral tellings and retellings. Churn and rechurn.

This is true in music, also. Not just the parody masses of the 15th century, or all those Baroque composers “borrowing” tunes from themselves or their contemporaries, or the many recomposings of La Folie, but more recently, Tchaikovsky rescoring Mozart and Glazunov turning Chopin into the ballet Les Sylphides.

Of course, all the arts build on previous, if not through quoting or re-use, but at the very least just by existing in a continuum of culture. You could not have had the Renaissance without Classical Rome, or Hedda Gabler without As You Like It. All one forward surge.

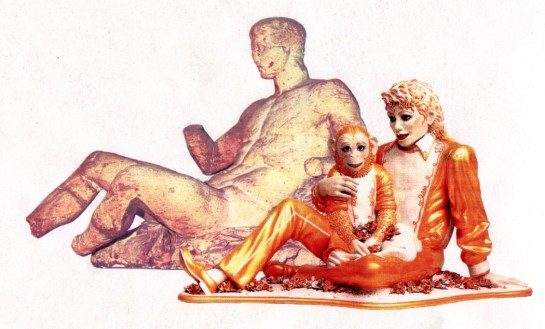

All art is, on one level, a conversation with the past. Even Jeff Koons’ sculptural portrait of Michael Jackson and Bubbles is a gloss on Pheidias’ statue of Dionysos from the east pediment of the Parthenon from the Fifth Century BCE.

Or, take Manet’s Olympia, which ironically quotes Titan’s Venus of Urbino. (I wrote an exhaustive essay in “Meme and Variations,” from this blog in 2014. Link Here)

Manet was tweaking his nose at the Renaissance painting, and in 1920, Igor Stravinsky was doing something similar to what he assumed was the music of Giovanni Pergolesi, in his ballet score, Pulcinella.

In 21 movements, he rebuilt and re-orchestrated the 18th-century music and made it sound utterly Stravinskian. “Uncle Igor’s Asymmetry Machine,” as Leonard Bernstein called it. Catchy tunes and astringent orchestration. (The fact that the source-music wasn’t Pergolesi but mostly keyboard music by Milanese composer Carlo Ignazio Monza and trio sonatas by Domenico Gallo, a lesser known Venetian composer, both of whose works were sometimes bootlegged under the more salable name of Pergolesi. A YouTube video with the original compositions is available. Link here)

It’s surprising how little Stravinsky changed his originals, except by a little nipping and tucking, and using brilliant and cheeky orchestration.

But this habit of updating ancient music was a frequent technique among composers, especially in the 20th century. Stravinsky himself applied the spice to Tchaikovsky in Le Baiser de la Fée (“The Fairy’s Kiss”) from 1928.

When I was a young recent college graduate, with little or no money in my pocket, I found a battered LP in a castaway bin of a local bookstore. It was on an Eastern European recording label, perhaps a Soviet one, lost to time and my ancient loss of memory. It cost 98 cents and contained William Walton’s The Wise Virgins on one side and Domenico Tomassini’s The Good Humored Ladies on the other. That LP’s fate is lost to 60 years of peregrination, and I only recently found a CD with these works on it. I was emotionally transported to another time and place.

The Walton was a re-orchestration and revamp of work by Johann Sebastian Bach, and the Tomassini did the same with music by Domenico Scarlatti. Both were designed as ballet scores.

(Scarlatti’s keyboard sonatas were first orchestrated in 1743 by English Baroque composer Charles Avison in 12 Concerti Grossi After Scarlatti, but Avison did the opposite of Stravinsky: He smoothed over Scarlatti’s pungent harmonies and expressive dissonances, to make them “pretty.” Avison did the same for a dozen violin sonatas by Francesco Geminiani.)

All this piqued my interest, and I spent the past week listening to recordings of all the refurbished music I could find, and there is a lot of it. Two people, in particular, are the source for a great deal of it.

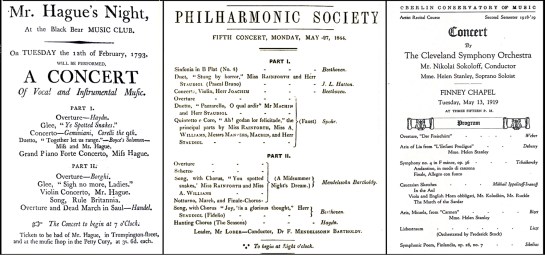

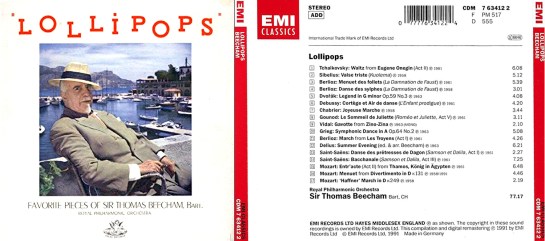

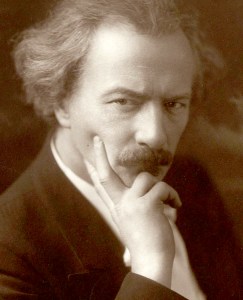

The conductor Thomas Beecham performed the music of Handel back in the early 20th century when Baroque music was practically unheard, outside of the annual Messiah productions. But Beecham not only recorded whole Handel operas and oratorios, he brought excerpts of them into ballet scores he compiled, with his own modern re-orchestrations of them, but often played bits in his concerts.

The best known is probably Love in Bath, a ballet score made from arias, choruses and sinfonias from various Handel works, in rescorings much less snarky than Stravinsky’s, and entirely pleasant on the ear.

He began with The Gods Go a’Begging in 1928, then The Origin of Design (1932), The Faithful Shepherd (1940), Amaryllis (1944), The Great Elopement (1945) and finally, Love in Bath (1956). They often varied each time he presented them, changing suite movements according to his pleasure each time they were programmed.

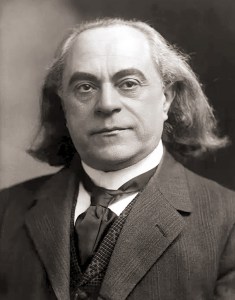

The other popular champion of ancient music was Ottorino Respighi, who made popular hits out of Renaissance and Baroque lute and keyboard music, most famously in his three suites of Antiche danze ed arie (“Ancient Airs and Dances”) which he wrote from 1917 to 1931. They remain popular in concert and have often been recorded. It’s hard not to love them and whistle the tunes for the rest of the day.

Then, there’s Gli Uccelli (“The Birds”) from 1928, in which Respighi orchestrated keyboard pieces by early (mostly) Italian composers from the 17th and 18th centuries. And Vetrate di chiesa (“Church Windows”) from 1926, based on Gregorian chant and plainsong.

Richard Strauss wrote two suites updating and orchestrating keyboard music by François Couperin. First, Tanzsuite (“Dance Suite”) from 1923, consisting of eight movements, and then Divertimento, from 1942, with 25 keyboard pieces arranged in eight movements.

In 1935, Francis Poulenc wrote a suite for wind band, called Suite Français, using the tunes of 16th century composer Claude Gervaise.

And among the most popular pieces from the 20th century was a four-movement guitar concerto, based on six compositions by the 17th century Spanish composer Gaspar Sanz. It was written in 1954 by Joaquin Rodrigo and titled Fantasia para un Gentilhomo (“Fantasy for a Gentleman”) Dozens of guitarists have recorded it.

Rodrigo also put together an eight movement suite called Soleriana, orchestrating the harpsichord music of 18th century composer Antonio Soler. I had a hard time tracking down a recording, but I found one and have to say it was just as catchy and memorable as the Fantasia.

Finally, among works of this kind, I should mention Peter Warlock’s Capriol Suite, built, according to the composer, on tunes in Thoinot Arbeau’s Orchésographie, a manual of Renaissance dances.

But all this rewriting and modernized orchestration wasn’t only applied to antique music. There’s plenty of 19th century music that gets reworked, usually to accompany a ballet. And a lot of them get named some form of “ianna.” Like Mozartiana, Rossiniana, Paganiniana, Soleriana, and Offenbachiana. (Not to mention Bachianas Brasileiras, but that’s another thing.)

Gioachino Rossini wrote 39 hugely profitable operas by the age of 39. Then, in 1832, he retired to live comfortably for the next 40 years. But starting in or about 1857, he began writing short pieces, songs, piano works, choral works — some 150 of them — meant for friends and family and never intended for public performance. He called them his Péchés de vieillesse – “sins of old age.”

In 1918, Respighi orchestrated nine of these “sins” for a ballet, La Boutique Fantasque. It remains enormously popular with dozens of recordings. Later, in 1925, he dove back into the collection to “freely orchestrate” his Rossiniana.

Benjamin Britten used bits from Rossini’s late works for his Soirées Musicales from 1937, and later, his Matinées Musicales from 1941.

Strangely by default, French composer Manuel Rosenthal was tasked with selecting and orchestrating music by operetta champion Jacques Offenbach for a Massine ballet, Gaité Parisienne, in 1938. It remains popular in concert. Then, in 1953, he dipped once more into the well for Offenbachiana.

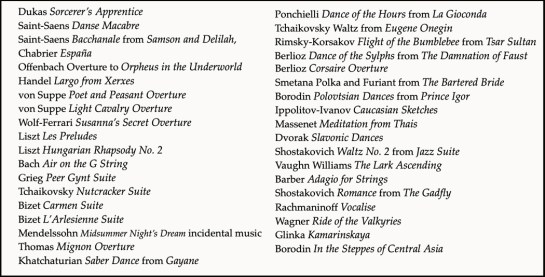

But let’s face it, this becomes a rabbit hole: There are endless workings and reworkings of music, turning piano pieces into orchestral showpieces, or chamber works into ballets. I should mention just a few of the most famous or popular.

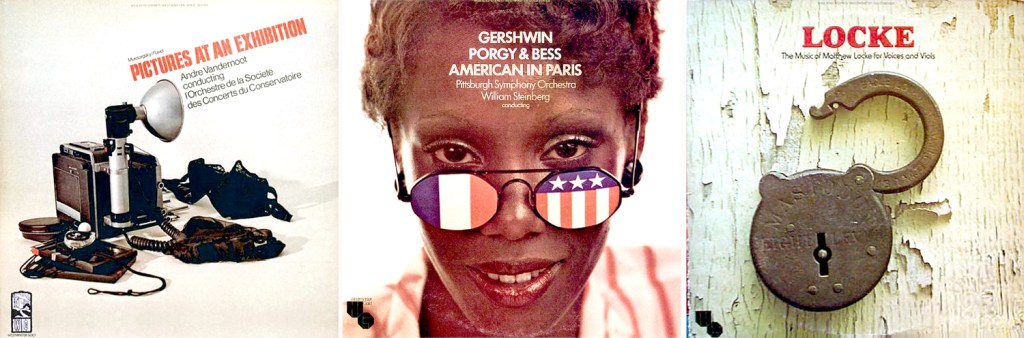

Maurice Ravel took Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition and did such a number on those short keyboard works, that some people are shocked to discover they weren’t originally written for the orchestra.

Leopold Stokowski made a career of turning Bach organ works into hyper-lush symphonic showpieces. (He was also not shy about changing around, cutting, or adding cymbals or tam-tam crashes to established symphonies.)

Arnold Schoenberg decided to orchestrate Brahms’ G-minor piano quartet because, he said, “1. I like the piece; 2. It is seldom played; and 3. It is always very badly played, because the better the pianist, the louder he plays, and you hear nothing from the strings. I wanted once to hear everything, and this I achieved.” He was also commissioned to do it by L.A. Phil conductor Otto Klemperer, where it was first played in 1937.

And finally, I should mention Duke Ellington, who recorded his jazz-orchestra versions of both Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite, and Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite. Both hugely fun.

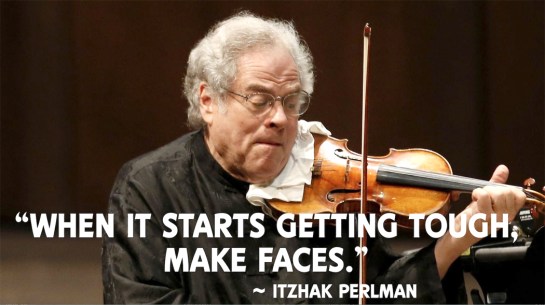

It never ends. Kismet, a broadway musical with songs borrowing tunes by Borodin. A nearly infinite number of variations by a nearly infinite number of composers on Paganini’s 24th Caprice for solo violin. All those “Reminiscences” of various operas for solo piano by Franz Liszt. Charles Gounod’s Ave Maria built on top of Bach’s C-major prelude from the Well Tempered Clavier. Franz Waxman’s Carmen Fantasie. Paul Hindemith’s Symphonic Metamorphoses on Themes by Weber.

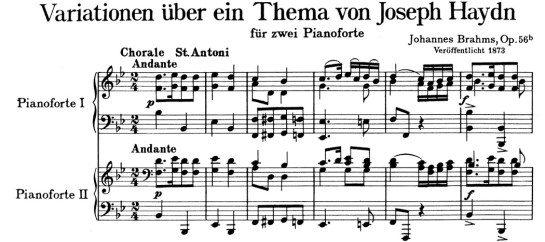

And let’s not leave out Brahms’ Variations on a Theme by Haydn, which was on a theme Haydn had borrowed in the first place. He didn’t write it.

A quick check of Wikipedia lists hundreds, perhaps thousands (too many for me to count and still have a life) of “variations on” or “hommage to” or quotations from or transcriptions of orchestral music for home piano, or vice versa, piano music turned orchestral. No Haydn, no Beethoven, no Beethoven no Wagner, no Wagner, no Schoenberg, no Schoenberg, no Lutosławski. Piles on piles.

So, this idea that anything Postmodern is new needs to be chucked out the window. Postmodernism is a catchall phrase, with rather more meaning in architecture than in art or music. After all, we’ve been feeding on the past since the beginning.