“You’ve gone all mellow,” Annie said, teasing me.

In the past, I have had some rather unforgiving opinions about the poetry I was force-fed as a youngster — you know, the Victorian stuff about the light brigade, or Barbara Frietchie. And now, I was reading it again. On purpose.

At college, I foolishly took a Victorian Lit course and hated every second-hand tick of the classroom clock. Turgid, sentimental, maudlin, and unbearably prolix. (I had been primed to hate the stuff since the time I was forced to read Oliver Twist in eighth grade and hated every word of that — I still can’t read Dickens. I know: My loss. But you shouldn’t be forced to read stuff before you are ready for it.)

In that Vic Lit course, I found Browning asphyxiating, Tennyson hollow, Christina Rossetti cloying. I could see no difference in the verse of these hallowed poets from the mewlings of Ella Wheeler Wilcox or Edgar Guest. It was all a smear of treacle and oh-so-earnest goo.

“I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul.” Who came up with this stuff?

Now, Anne is reminding me, I am waxing enthusiastic about the selfsame verse to her, quoting lines and rhymes with affection. I have gone mellow. But what has changed?

I grew up in a time of ascending Modernism, an era of “less is more,” of irony sidelining sentiment and of skepticism in place of belief. When I was just on the cusp of turning adolescent, Modern art was still widely dismissed as something “my kid could do.” And in the eternal wheel of generations, I was signing on to the new version and leaving the old to such fuddy-duddies as my parents and teachers.

(At least, I saw it that way. In reality, my parents were as much a product of Modernism as I was — my father was born the same year that the Bauhaus was founded and that Marcel Duchamp painted a mustache on the Mona Lisa. But the Modernism that affected his life was one of wars, electrification, washing machines and radio. Artistic matters mattered not at all to the solid, middle-class parental units.)

And, like all such newly-awakened youths, I saw through the lies and hypocrisies of the elder generations while surpassingly blind to my own. My generation was going to fix all the botches those fools had made of the past.

I read all the most current novels, ate up contemporary poetry (and all that written after Prufrock), regularly made my pilgrimage to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and preached to all near and far the supremacy of the new.

In short, the modern was true; the old was a lie. A pretty lie, perhaps, but a lie nonetheless. As H.L. Mencken put it, “it’s essential character lies in its bold flouting of what every reflective adult knows to be the truth.”

And all that verse: Mencken really had it in for poetry. He said, roundly including everything written from Chaucer to e.e. cummings, “Poetry represents imagination’s bold effort to escape from the cold and clammy facts that hedge us in — too soothe the wrinkled and fevered brow with beautiful balderdash.”

That certainly summed up my take on Tennyson: “balderdash.”

H.L. was not one to hedge his opinions. He went on to call poetry, “a series of ideas, false in themselves, that offer a means of emotional and imaginative escape from the harsh realities of everyday. In brief, poetry is a comforting piece of fiction set to more or less lascivious music.”

But it is that “lascivious music” that caught me short. No doubt Mencken rather misses the point, but it is the music of the old poetry, the poetry I so despised, that has brought me back to it. Let me explain — and apologize.

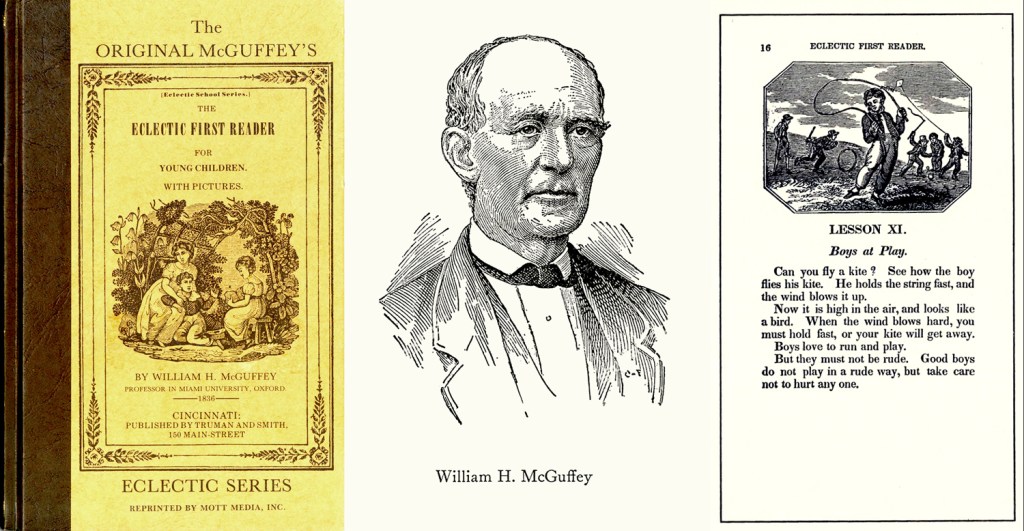

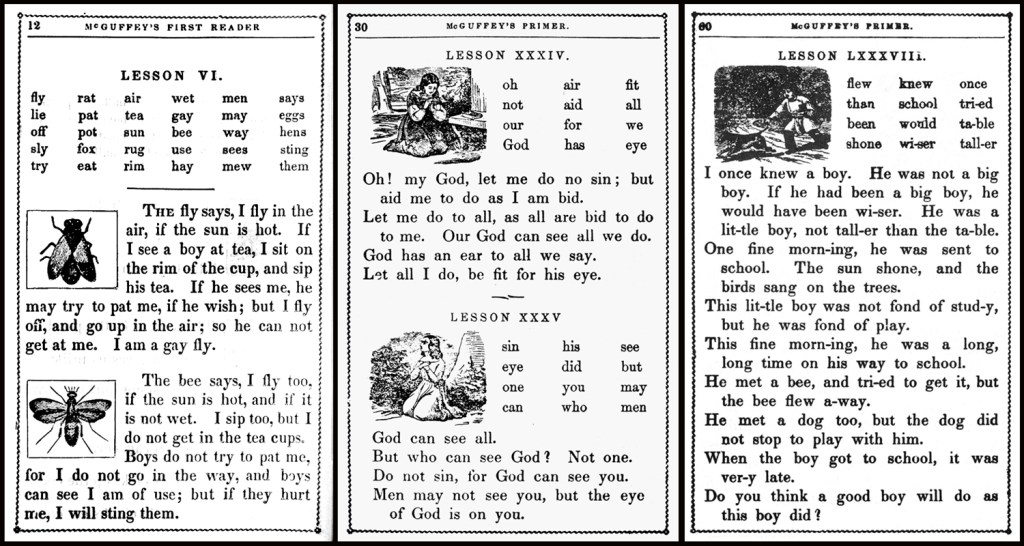

It started when I recently came across a set of McGuffey’s Eclectic Readers, compiled beginning in the 1830s by William Holmes McGuffey. The books were the most common grade-school texts for nearly a century, and are still the preferred books for many current home-schoolers.

They are popular now because of the unrelenting Victorian religiosity of them for Christian home-schoolers. Every lesson seems to have some biblical homily to teach, training youngsters to be pious, faithful, honest, loyal, earnest, frugal and industrious. McGuffey, himself, was a preacher, in addition to being an educator and college president.

But what is often lost in the haze of piety, is just how progressive McGuffey was for his time. Most education was then mere rote memorization enforced with the rod; McGuffey thought that instead of just giving kids lists of words to master, it would work better if the words were embedded in stories, and that new words in one story would crop up again for reinforcement in later stories. He taught an early version of phonics, to parse out the sounds of written words, and followed each story-lesson with a short set of questions to test comprehension.

Really, aside from the heavy Jesus-ness of it all, it was really very forward-looking.

I valued the reprints I own for their classic typography, for the quaint illustrations that go with the stories, and for the insight the whole gives me into that formidable century.

And in amongst the stories of boot-blacks making good, mothers dying, little orphans learning the virtues of truthfulness and the importance of being generous to the poor, McGuffey included many old poems. Some are just versifications of Bible passages, but others are the old standards that I once made fun of.

For instance, in McGuffey’s Eclectic Third Reader, I came across an old chestnut I had not encountered since I was a boy: The Moss Covered Bucket, by Samuel Woodworth. It’s one of those that most people have some vague recollection of, but perhaps not where the lines come from or what they mean.

“The old oaken bucket, the iron-bound bucket, the moss-covered bucket, which hung in the well.”

But as I began reading it, I found two very surprising virtues. The first was how much sense-memory there was in the poem — the noticing of small physical things that connect us with the world and that readers can almost feel, taste, or smell as they read the lines.

It is a poem about remembering the things of youth, and there is a scent of sentimentality to it, but the memories evoked feel genuine. Sometimes, reading a pile of “O thou art…” poetry you wonder if a poet has ever actually seen a nightingale, let alone a “knight with burning brand,” but have merely read about such things in other poems. But here, I believe Woodworth really knew “the orchard, the meadow, the deep tangled wild wood… the wide spreading pond, and the mill which stood by it; the bridge and the rock where the cataract fell; the cot of my father, the dairy house nigh it, and even the rude bucket which hung in the well.”

Noticing — as I have often repeated — is essential to art. To life.

But the second thing I found in the poem was the “lascivious melody.” Woodworth’s prosody was finished and refined, the meter and rhyme made the lines sing. Maybe not quite the level of Milton, but a danged good ditty.

He describes coming in from working in the field and dropping the bucket down into the well “to the white pebbled bottom it fell,” and then how “dripping with coolness,” it rose from the well. “How sweet from the green mossy brim to receive it, and posed on the curb it inclined to my lips! Not a full blushing goblet could tempt me to leave it, though filled with the nectar that Jupiter sips.”

It moves with a forward-thrusting momentum hied on by the meter.

I’m not trying to make too great a case for the old oaken bucket. It is not earth-shaking poetry. But it does afford a moment of pleasure as you read it, the way you get pleasure from a memorable tune.

There were other poems in the Reader that now sang to me in ways I had formerly ignored. Byron’s “The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold, and his cohorts were gleaming with purple and gold…”

In the Eclectic Fifth Reader, compiled some years later by McGuffey’s brother, Alexander Hamilton McGuffey, you find the familiar, “Under the spreading chestnut tree the village smithy stands; the smith, a mighty man is he, with large and sinewy hands; and the muscles of his brawny arms are strong as iron bands.”

There is through all of the Readers a level of maudlin sentimentality that cannot be overlooked, but if you can wade through that, there are some true gems to enjoy, if primarily for their lascivious music.

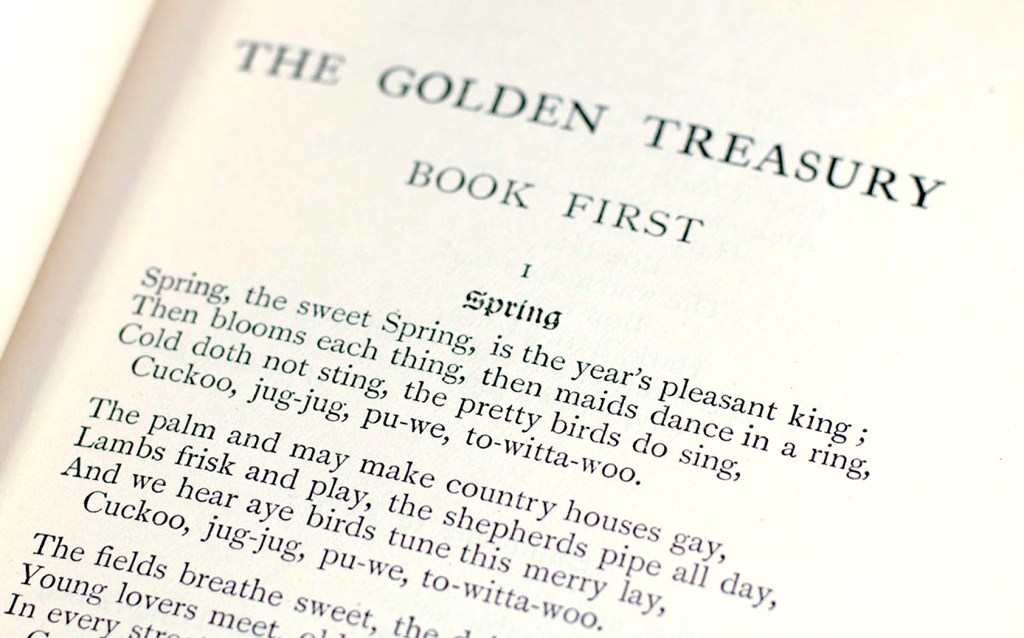

This discovery led me to another old book, one I have owned since I was a boy, but had hardly looked at in 60 years: Francis Turner Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of English Verse. First published in 1861, the book was an anthology of “the best English songs and lyrics,” and included Palgrave’s selection of verse written by poets of the past — his past; Palgrave made the decision not to include any poetry written by living poets, so, no Tennyson, no Browning.

The book was originally divided into four “books,” one each per century from the Elizabethan era to the 19th century. There is a good deal of Shakespeare and an equal measure of Wordsworth, but all the usual names are included, and some that have largely been forgotten. Thomas Grey, William Cowper, Thomas Wyatt, Josuah Sylvester (no, that’s not misspelled).

Having put aside my McGuffeys, I took up my Palgrave and read it from cover to cover. I found myself enjoying page after page, for the music of it more than for the sense. A good deal of the early verse is highly conventional in sentiment. Everyone had a version of “carpe diem,” many birds are extolled — I haven’t counted the skylarks, but there be many — many women described with coral lips and alabaster skin. It all gets a bit thick.

But listen to the music instead. “Whenas in silks my Julia goes Then, then (methinks) how sweetly flows That liquifaction of her clothes.

“Next, when I cast mine eyes and see That brave vibration each way free; O how that glittering taketh me!”

There is a perfection in the meter, rhythm and rhyme to Herrick’s little stanzas. Felix Mendelssohn wrote “Songs Without Words,” but Herrick has turned that around and written a song without the sheet music.

Throughout my Palgrave, I came across piece after piece like that, with a flow of words as natural in metrical expression as a stream rushing over its rocky bed.

“The curfew tolls the knell of parting day, The lowing herd winds slowly o’er the lea, The plowman homeward plods his weary way, And leaves the world to darkness and to me.”

“A chieftain to the Highlands bound Cries, ‘Boatman, do not tarry! And I’ll give thee a silver pound To row us o’er the ferry!’ ‘Now who be ye, would cross Lochgyle, This dark and stormy water?’ O I’m the chief of Ulva’s isle, And this, Lord Ullin’s daughter.”

The marriage of word and rhythm, with the fulfilled expectation of rhyme make these verses trot along like a tune sung well in time.

It is the pleasure of tennis being played with a net.

One listens to music for the pleasure it brings. Yes, there are mighty symphonies and Wagnerian music dramas meant to express deep emotional and philosophical things, but most, like a Mozart serenade or a Cole Porter tune, are meant to delight, devoid of any extra-musical sense. And that is what I am finding in this old verse I once so roundly denounced.

If you don’t need to have profound thoughts as you read the words, then you can find the melody for its own sake and revel in the ear and craftsmanship of the poet.

Yes, I’ve gone mellow in my senescence, and there is a touch of sentimental remembrance for the poetry I was fed when a boy. I guess I share that with those horrible Victorians. That is my apology.

Click on any image to enlarge