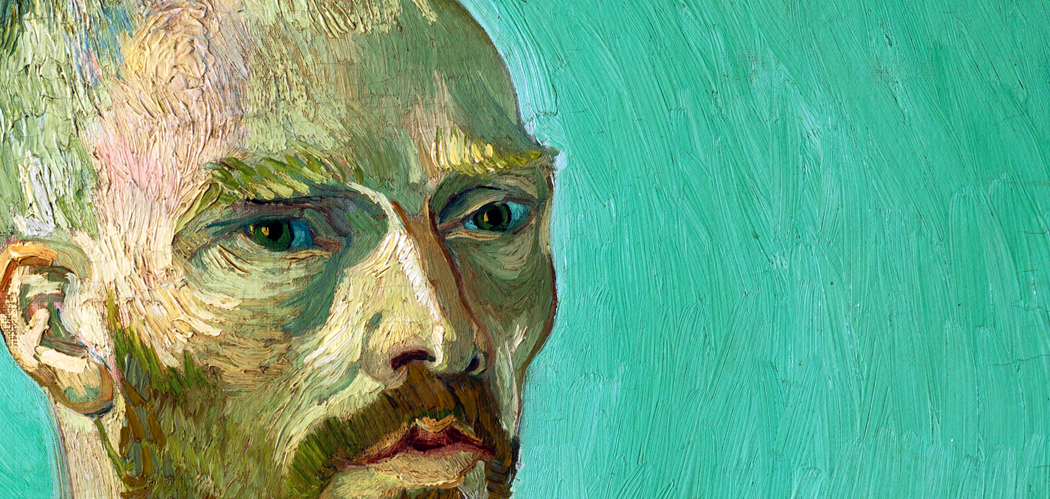

Take two of the most famous paintings in the Louvre. Most of us first experienced them in pictures in a book, perhaps Janson’s History of Art in an art history class. Or, projected onto a screen in the darkened classroom while the teacher pointed out details of the iconography. But these are images, not paintings.

Often, today, we confuse the two, seeing pixels on a cellphone or iPad, and can easily believe we know the art because we can recognize the familiar shapes and colors. That is why so many people remark, on visiting the museum in Paris, about how “small” the Mona Lisa is.

It’s not that small, of course. It’s a fairly normal size for a Renaissance portrait, but the fact is that separated out, as it is, for display, it takes up precious little wall space. Really, most people hadn’t given any thought to the actual size of the painting when seeing the reproduction in a book. It’s just an image, an icon, familiar not only in its regular shape, but also parodied to death in comic take-offs.

You could look at the caption next to the printed image in your book, and see that there is a bunch of information in parenthesis beyond the identification of artist and title. It will often give you the date, in which museum collection it resides, and the size of the painting. In the case of the Mona Lisa, 21-by-30 inches.

But then, perhaps you wander into the gallery with Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa. You’ve seen it in your Janson and think you know it. You don’t. It is 16-by-23 feet — the size of a billboard.

You see them as images, and they are adjusted to the size of the page and you can have no sense of their relative sizes.

But walk through the Louvre and it is quite different.

I remember when I was a teenager and going to the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan and seeing Picasso’s Guernica, which stretched out across its own wall. You could see it from afar, stepping out of the elevator and looking to your right, several galleries away. Just under 12 feet high and 26 feet across, it was more than a painting and more than an image. It was a presence.

And that was part of its meaning. It was made in outrage over the 1937 German bombing of the Basque down in Spain and if it had been made to display comfortably on a gallery wall, it would have been just another painting for sale. But at size, it forces you to consider the suffering and death. Its size means you cannot just look away.

The world we live in is increasingly a virtual one. The TV screen, the computer screen, the cellphone screen, the tablet and even the wristwatch screen have become so normal to our daily lives it has become easy to mistake what we see there as real. It is not.

You cannot have the personal experience of Guernica from a photographic reproduction or a pixel image. You can memorize its iconography and discuss its provenance and the biography of its creator, but you will not have the gut-level experience of it I had visiting it at MoMA.

And it isn’t just the size. Seeing art in person means you can see the pigments used, the brushstrokes, the opacity or transparency of the paint, whether it is on panel or canvas — a whole range of physical properties not apparent in a reproduction, and all of it — in addition to its physical dimensions — are essential to its meaning.

And by meaning, I don’t refer to its symbology. That is language. I mean the experience of it. Vermilion or ultramarine are experiences not conveyed in ink or pixel, and that experience is meaning.

If you walk through the Louvre, another famous art history painting you find will be Veronese’s The Wedding at Cana. Another wallop in the gut. It is 22 feet high and 33 feet from side to side.

If you think of it as a biblical subject, and believe you are “getting” the painting by naming the people pictured, you have missed the central experience of the work.

Even more ordinary size paintings depend, in part, on their dimensions and how you relate to them. A life-size portrait can mimic meeting the person himself. In the Renaissance, one ideal was that a painting should be like a window through which you are looking, and so a window-size canvas was part of the experience.

A giant head is another thing altogether, like the famous head of Emperor Constantine or one of the Olmec colossal stone heads from Mexico. Their size makes you take notice. The same shape, but the size of a cantaloupe, would hardly carry the power of these monuments. I remember the first time, as a boy, I saw the Olmec head at the American Museum of Natural History in New York; the memory of it stuck to my psyche for decades after. Still does.

The same for the huge portrait heads of Chuck Close.

The word often used to describe such larger-than-life art is “heroic.” They have an effect very like that of Achilles in the Iliad or Ahab in Moby Dick. It is a word often used to describe the large paintings of the Abstract Expressionists of the late 1940s and through the 1950s. These were painters of utter seriousness of intent. The last gasp of a non-ironic age, after which came the deluge of meta.

There are artists who use mere size to impart meaning to their work, Anish Kapoor, for instance, in his huge shiny bean called Cloudgate, or the rusted steel curtains by Richard Serra that are best experienced by walking through. But notice that the giant bean is also ironic. It’s a bean, after all, raised to heroic proportions.

But those cigarette-smoking, heavy-drinking and blue-collar wearing guys at mid-century were dead serious. Jackson Pollock painted his first large painting, called Mural, in the mid-’40s. It is 8 feet by 20 feet and meant to be installed in the apartment of Peggy Guggenheim. It led to the later drip paintings that made Pollock famous — in 1949, Life magazine asked “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”

Pollock made paintings in various sizes, but it is his large canvases that hold the emotional power that still resonates today. I visited the huge Pollock retrospective at MoMA in 1998 and was blown away by the variety of the paintings, and got a chance, finally, to see Blue Poles, a large 1952 canvas sold to a gallery in Australia in 1973 and unavailable to American audiences since then. It was given pride of place in the exhibition and deserved it, in the center of the room, on a wall of its own. It was lit like a jewel, but a jewel 16 feet across.

Most of the Abstract Expressionist gang trafficked in scale. Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Willem de Kooning, Clyfford Still — all found now in museums taking up whole walls by themselves.

In the 1970s, I wandered through commercial galleries in New York and came across a back room storage of Newman paintings, being arranged for a show, and a group of them were almost two stories tall — monumental. These men (and they were almost all men) took their heroic calling seriously.

After them, the deluge. Even Motherwell turned to irony; the self-importance of the first generation could not be sustained, or even taken seriously anymore. And although Robert Rauschenberg is sometimes classed among the Abstract Expressionists, his work always played with irony.

All that was left after that was Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons. Art took a different turn.

When the Getty Center opened in Los Angeles in 1997, I was an art critic in Phoenix, Ariz., and given the assignment of covering the event. I met with Robert Irwin, who designed the landscaping for the Getty, and had a concurrent museum show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in LA. In a hallway, away from the main work in the exhibit, were a series of early paintings he made. Irwin was a thoughtful artist and his eyes glistened as he discussed those small, early canvases.

“I was thinking about the heroic nature of those Abstract Expressionist paintings,” he said. “And I wondered if they could still work if they were small.” And so, he painted a line of tiny canvases, usually no more than a foot square, with similar abstract imagery on them. Did they work? Were they still heroic? Do you have to ask?

Click on any image to enlarge