I once made a list of my Top Ten Films and the list had 40 movies on it. What is more, if I had made the list a year before, or a year later, the 40 movies might have been quite different. One cannot really pick a permanent set.

So, when Classics Today executive editor David Hurwitz published his list of “12 Operas I Cannot Live Without,” and challenged his audience to come up with their own lists, the same problem popped up. “You mean the dozen I cannot live without today?”

While I love opera, like Hurwitz, I have to admit I am not an opera nut. That’s a different breed. Opera does seem to attract the crazies — the ones who swear by a 1948 barely audible recording, made over a telephone line, of Maria Callas singing La Sonnambula — in the unauthorized 1848 edition only performed once, in Belfast, Ireland in 1873. You know, the one with the interpolated aria in Act 2. Yes, crazy like that.

I have been listening to classical music for more than 60 years, and am a classical music generalist: I love it all, from pianists to chamber music to symphonic and vocal music — and, of course, opera. But opera has no special place for me. Opera people care who the tenor is; I am more interested in the composer, which means I’m not included in the opera inner circle.

So, my list is not made up of the usual names: Verdi, Bellini, Puccini, and doesn’t automatically include the ABCs of opera popularity — Aida, Boheme, Carmen. It’s not that I dislike them, but I have seen them enough times that I don’t need to experience them yet again. They will always sell enough tickets, even without my attendance.

These are the works that I choose when I want to hear opera, to enjoy the music in them and the emotions they arouse. I could list more than 12, but Hurwitz’s assignment limits the number — although I might cheat a bit.

1. Handel: Rodelinda

The first opera I ever attended was in 1966 when the Handel Society of New York staged Rodelinda at Carnegie Hall with Teresa Stich-Randall and Maureen Forrester with a pick-up pit orchestra conducted by Brian Priestman. I couldn’t stop humming the tunes.

Years later, I found a three-disk LP album of the opera in a smooshed-up box in a thrift store. I don’t remember who performed it, probably some Eastern Europe company on a back-water label no one’s ever heard of. I played it over and over. The familiar melodies were comforting.

The same year I saw Rodelinda, the same group also performed Xerxes and I saw that, too. Since, I have seen Giulio Cesare live and a truly brilliant staging of Semele by the Arizona Opera Company, but it is Rodelinda that sticks.

2. Mozart: Don Giovanni

The opera I have seen most, and that I love as music as well as theater, is Don Giovanni. I’ve seen it more often than any other live opera (except the infinite Bohemes and Carmens I saw through duty as my newspaper’s opera critic).

Most operas, even the really good ones, can not be defended on the basis of their plots, which are, at best, nonsensical and goofy. But Don Giovanni has a story with action, believable characterizations, and psychological subtlety. To say nothing of some really great tunes.

And it is a truly revolutionary work, written at a revolutionary moment in history. I love when the partygoers at the end of the first act just kind of stop everything and belt out the words, “Viva la Libertad!” And also that, at the end, the Don has the courage to refuse to repent. He may be the villain of the piece, but he is also the hero.

I’ve owned a half-dozen versions of the piece on LP and now CD, but my go-to performance is the oddly cinematic, opened-up film staging with Cesare Siepi as the Don, and conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler, available on DVD.

3. Mozart: Nozze di Figaro

On his list, Hurwitz permits only one opera per composer, but I can’t do that, because the three operas I love most, and can listen to over and over, are all by Mozart. Years ago, I wrote about what I was calling the “perfect” operas — that is, those with no longueurs, boring parts, added and unnecessary show-off arias to highlight the tenor or soprano. These are operas with plots that are defensible, if not great, pacing that doesn’t drag, and some level of human reality in them.

By any of those standards La Nozze di Figaro tops the list. These are all real people doing real people things, hurting like real people, loving like real people, and most importantly, forgiving like real people. And, all the the perfectly psychologically apt music of Mozart. If I were to choose the best opera ever written, this would be it.

4. Mozart: Zauberflöte

Talk of silly plots: Just about the worst story in opera is found in one of the most popular works. Everything about the story in The Magic Flute is preposterous. But the music is so infectious, you give up and don’t care.

Especially if you get to see the staging by Julie Taymor with its giant bunraku puppets. It is stage magic along with great music. It is a slightly abridged version and sung in English, but it is so good, and so much fun, you really have to watch it.

Or there’s Ingmar Bergman’s film version, sung in Swedish, which captures all the fairy-tale flavor of the thing. But really, there are dozens of recorded versions, both on CD for listening and DVD or Blu-Ray for watching.

5. Berlioz: Le Damnation de Faust

I hadn’t ever thought of it as an opera, but I saw the Metropolitan Opera staging of it in 2009 and was persuaded: It works really well in that Postmodern presentation. Actually thrilling.

As with so much of Berlioz, its reach much exceeds its grasp. Since the composer couldn’t include everything from even Part 1 of Goethe’s Faust, he chose to pick episodes to put to music, making a rather choppy story. Still, the music can be overwhelming when performed with the right belief and energy.

6. Wagner: Der Ring des Nibelungen

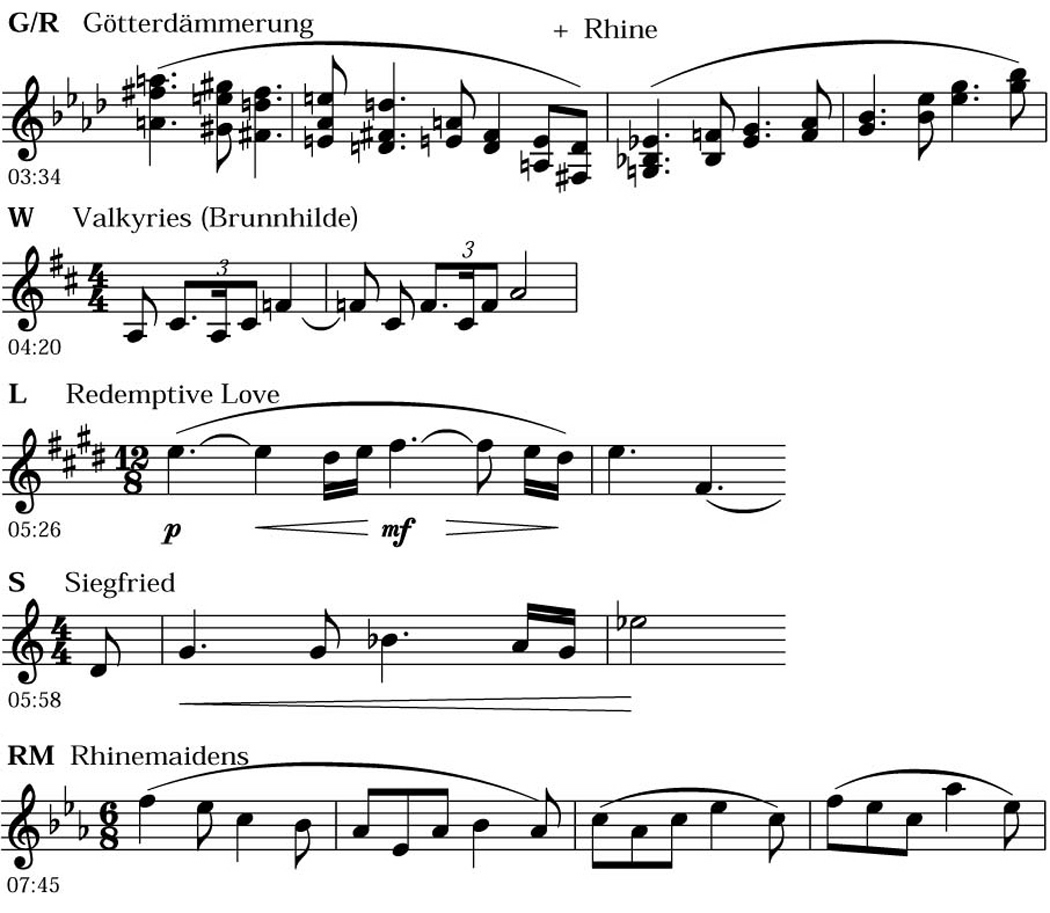

I’ve attended two live Ring cycles, which were quite magnificent (although I am humbled by the fact my dear friend, the late Dimitri Drobatschewsky went to Bayreuth 16 times). But I have to admit this four-opera trilogy (yes, that’s an oxymoron) is best heard on recordings. Not so much because with the great voices of the past, the singing is better (although that is true), but because the action in these “music dramas” is so mythic, and so German Romantic, that no scenery or stage machinery can adequately portray the Rhine maidens singing underwater, the valkyries riding their horses in the air, the gods crossing a rainbow bridge, or the Rhine river overflowing its banks to quench the fire that has set alight the entire world and ended the reign of the gods. Watching it onstage can seem a little tawdry.

But listening to the recording with your eyes closed and imagining the rocky crags, the dark forests, the ring of fire on the mountain top, is so much more convincing as theater of the mind. I say with eyes closed, but you really also need to read the libretto as you listen. Or not libretto — that sounds too much like opera — Wagner doesn’t have a libretto; he has a text.

I have five Ring cycles on CD (Barenboim, Böhm, Furtwängler, Janowski and Solti) and another two on DVD (Boulez and Levine). Is that a little nuts? I suppose. The one I listen too over and over is Solti, which was specifically designed to be played on speakers, with various sound effects added to it by producer John Culshaw.

And yes, I’m counting all 15 hours of the Ring as a single entry.

7. Offenbach: Les Contes d’Hoffmann

If the Ring is too serious, The Tales of Hoffmann counters with frivolity. I love this mini-trilogy (in four parts), especially when all three heroines are sung by the same soprano.

It has some of the chunky episodic feeling of the Berlioz, (compare the Chanson de Kleinzach tavern song here with Mephistopheles’ Song of the Flea in Damnation. Both completely extrinsic to the story, but a chance for the composers to interpolate a great bit of ditty.

The opera is a bit of a mess, as Offenbach never settled on a final version. But any version is a delight.

8. Strauss: Salome

I’ve seen several versions of Richard Strauss’ first opera, and it always seems to work on stage. It’s a short one, in a single act and tells of King Herod, his wife and daughter — Salome — and the prisoner John the Baptist, who Salome has a “thing” for. The prophet rejects her advances and she dances a striptease and has her daddy behead the prophet, whereupon she kisses the severed head. Grand Guignol, for sure, but great music and a surefire staging.

If the Ring fares best on recording, this opera needs to be seen live (or at least on DVD). It is as much theater as music.

9. Bartok: Bluebeard’s Castle

Another short, one-act work of psycho-sexual complexity, Bela Bartok’s early work, which seems to take place entirely in the nation of Allegory, tells the story of Duke Bluebeard and his new wife, who can’t seem to let alone the secrets of her husband’s previous marriages. She forces the secrets out and winds up prisoned with all of them. All very Freudian.

Those secrets are hidden behind doors, and as she opens each door, she finds a world of shimmering music and deadly horrors. There are only two singers/actors in this story, one who wants to uncover the past, and the other who begs her to let them lie. But it is the impressionistic score that makes this work so irresistible.

10. Berg: Wozzeck

There is a second “perfect” opera, after The Marriage of Figaro, one with no unnecessary bits, and everything leading to a single inescapable and shattering climax. It is written in a sort of atonal, 12-tone style (purely Berg’s own version) and is both musically inevitable, and emotionally devastating. Too many people avoid this work, fearing the music will be too dissonant, but every note serves a purpose, and even those fearing to enter the opera house will likely leave knowing they have experienced a work of utter genius.

I claim Wozzeck as my favorite opera of all. There are many versions on disc. This is another one, like Salome, where it is so well designed for performance that almost any version will do, and it’s amazing how many versions there are on Amazon. A serial opera that is actually popular!

11. Adams: Nixon in China

Initially, I thought this piece by John Adams was a gimmick, but I saw it performed in concert by the Phoenix Symphony under Michael Christie and it blew me away. As no other contemporary work for the opera stage, this has joined the repertoire. (Did anyone else notice how the showstopping aria, “I am the wife of Mao Tse Tung” is a gloss on the“Tuba Mirum” section of Mozart’s Requiem?)

No other figure in recent American history figures as so deeply mythic as Richard Nixon — a version of Nixon he seems to have bought into himself (check out the opening line of his autobiography: “I was born in the house my father built.” Can’t get much more Jungian.)

12. Golijov: Ainadamar

Christie also brought Dawn Upshaw to Phoenix to perform Osvaldo Golijov’s Postmodern take on the death of Spanish poet Garcia Lorca. With its mix of musical styles and bouncy, infectious score, it tells of the Spanish actress Margarita Xirgu, who recounts the life and execution of her friend Lorca.

Like all great tragedies, it is both depressing at emotionally exhilarating at the same time. To say nothing of it now being an uncomfortably historical warning about fascist governments.

There seems to be only a single recording of the opera, but with Upshaw in the lead role. The opera led me to seek out other music by Golijov, and I have loved all of it.

Postlude

You may wonder, where is Verdi? Rossini? Puccini? Are they not worthy? Of course they are, and I love them, too. And how can I have omitted Rosenkavalier, which I love to pieces? There is so much more that could have been included, from Monteverdi’s Orfeo to Weill’s Dreigroschenoper.

But this is a list of operas I can’t live without, the ones closest to my heart. The one’s that will make me actually buy tickets. Your list will be different, but if my selection prompts you to try something new, so much the better.

And, finally, seeing opera (with one exception, noted above) is always better than just hearing it. Live is best of all, but DVDs will do in a pinch, and many movie theaters present showings of operas live on their screens, most famously the Metropolitan Opera. Check with your local theaters to see where such performances might be scheduled.