Artist Mel Steele turned 85 recently. I have known Mel for nearly five decades, through the motorcycle years, the goat-herding years, the gun collecting years, the opera years. He is my brother-in-law and a friend. And I love his recent paintings as much as I’ve loved any art I’ve seen in person. So, I thought I might write a little something about his work.

I made my living as an art critic, and during my time as a journalist, I made it a practice never to write about the art of any of my friends, both because I feared insulting them through misunderstanding, but mostly because I wanted to avoid the charge of favoritism. (There were artists I wrote about who later became friends, but that was different.)

But I have been retired now for a dozen years, and I would not write anything about Mel’s paintings that I have not said to him face-to-face.

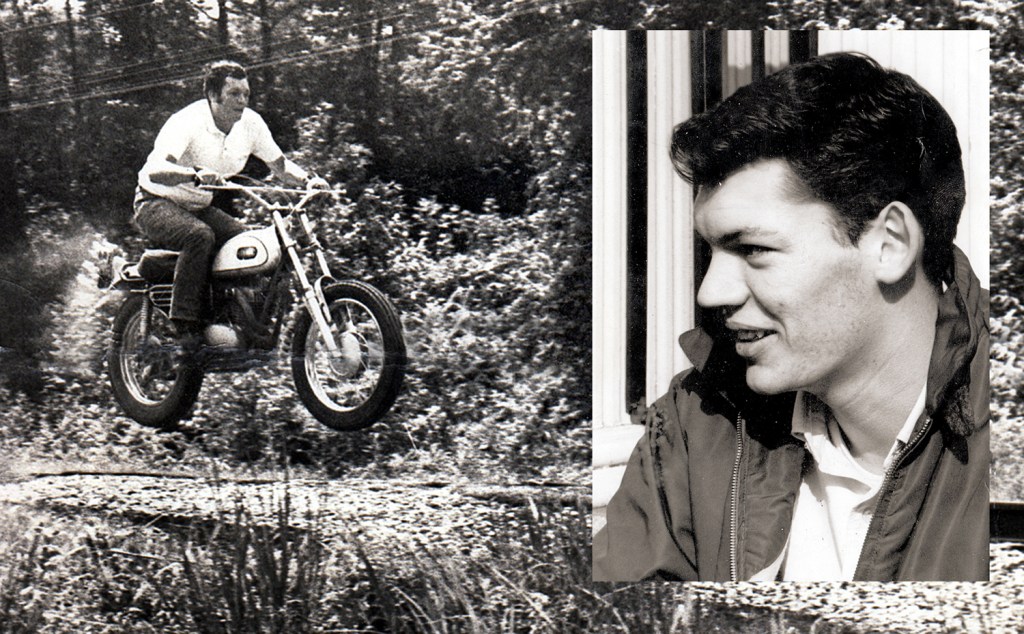

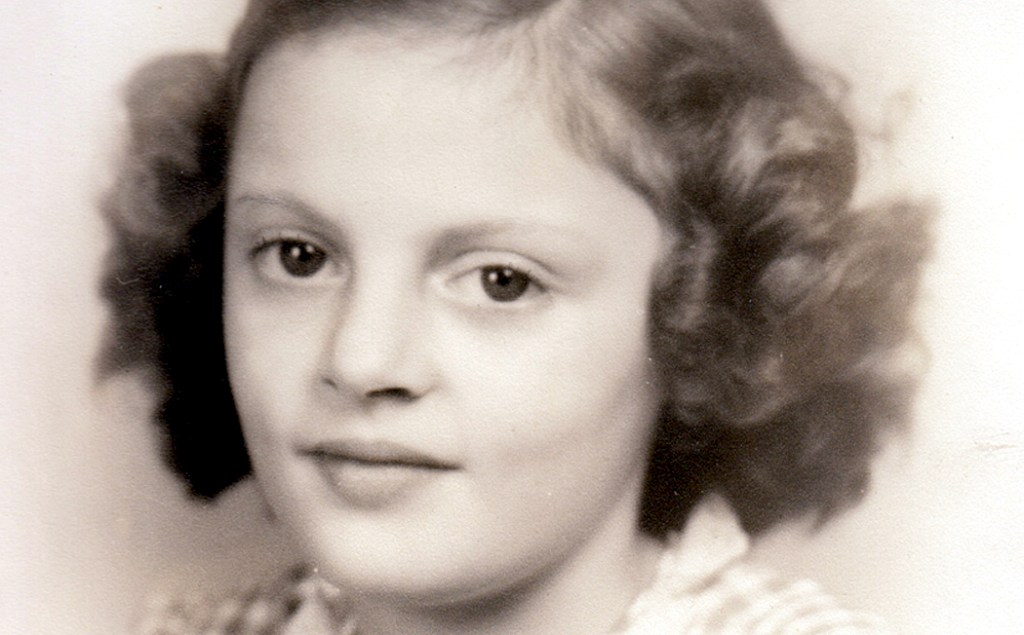

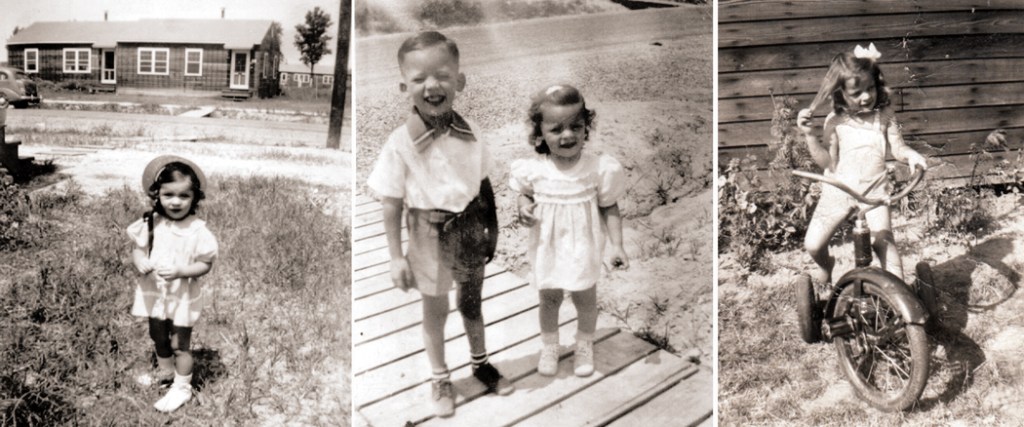

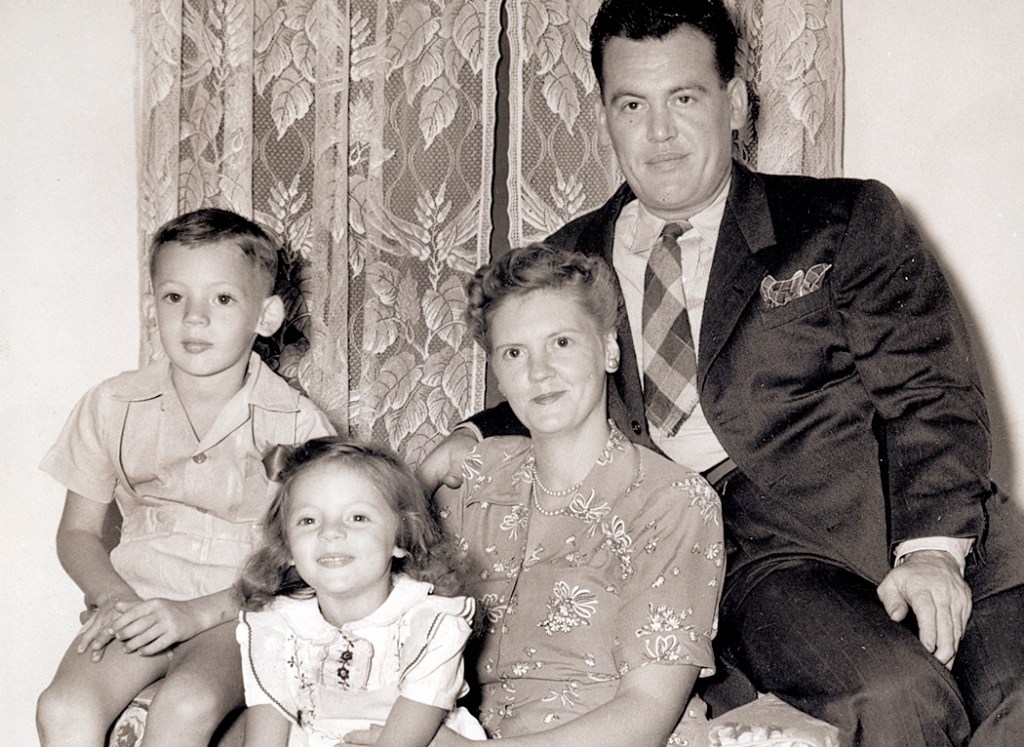

Mel Steele was born two years before America joined World War II, and was raised in Madison, N.C., about 30 miles north of Greensboro, and I doubt there was any question about what he would be when he grew up. From childhood, he had a brilliant talent for draftsmanship. I remember seeing a small painting of a rooster head he made when a schoolboy and it was as fully finished as any professional illustrator could have managed — almost photographic in its detail.

He has always drawn and painted animals.

But what do you become when you are an enormously talented child? There is not a lot of expectation for a rural North Carolina boy to become a famous painter. He could have grown up to become a plumber, like his father, and perhaps doodled on his customer’s bills.

He wound up going to the Richmond Professional Institute (now Virginia Commonwealth University) at age 20 and became a commercial artist, graduating from talented amateur to knowing professional. Commercial art seemed like the only meaningful way to use his gifts. Selling paintings in art galleries is an iffy prospect; a paid job is more dependable. As fashion-photographer great Richard Avedon once said about his own choice, “You can’t really make a living photographing trees.”

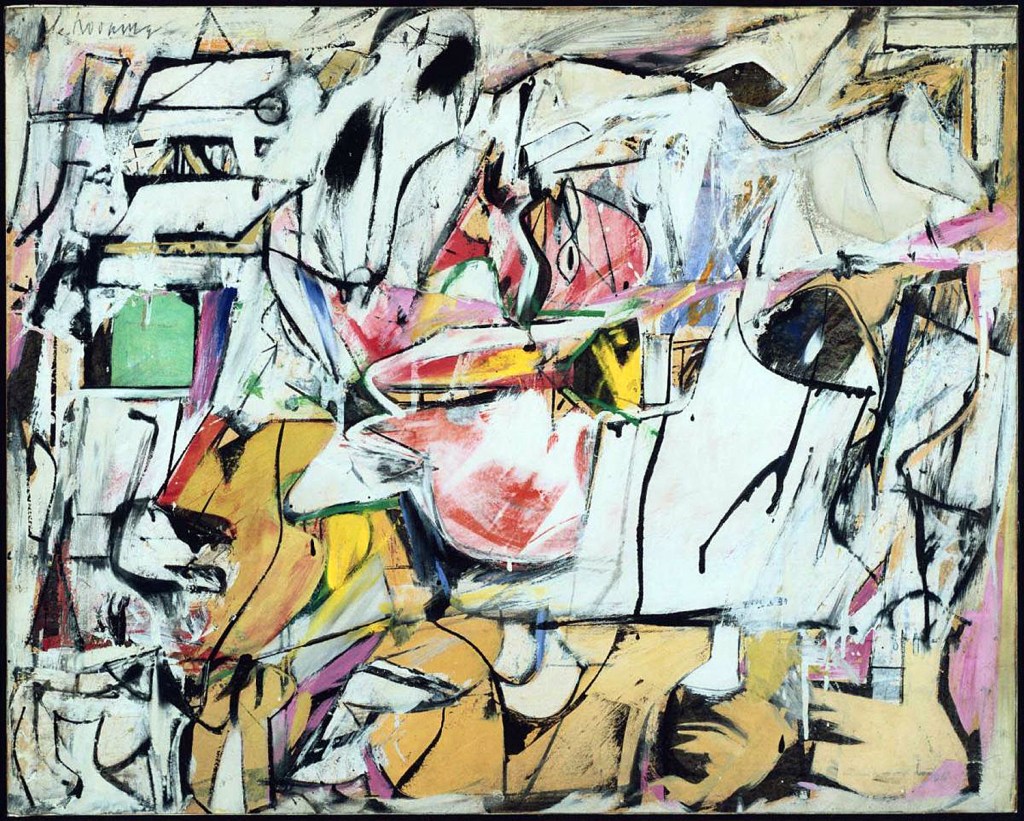

Yet, at school, Mel was introduced to the larger world of contemporary art. It was 1959, and New York had become the world center for art, with the buzz of abstract painting at the center.

Mel entered school wanting to paint like Norman Rockwell, but, as he says, “Most of the leading guys weren’t teaching just the standard way; they were teaching what was going on right now.” And that meant Willem de Kooning, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg. Mel loved the new work.

“Asheville” Willem de Kooning, 1948

But there was still that need to make a living, and when he graduated, he worked in advertising, employed initially for Belk department stores. Later, he opened up his own agency in Charlotte, N.C. He was good at what he was doing, enough so that he could pick and choose his clients. And move out of the city to a farmhouse in Rockingham County, N.C., where he and his wife, Deborah Ballington, took up raising goats and chickens.

This is when I first came to know Mel and Deborah, when my wife — Mel’s sister, Carole —and I would visit and get fed goat meat (absolutely fabulous) and perhaps do a bit of target shooting in the yard. (I was introduced to the .45 caliber Browning semi-automatic pistol, which had the kick of an angry horse and could knock a tree stump off its feet.)

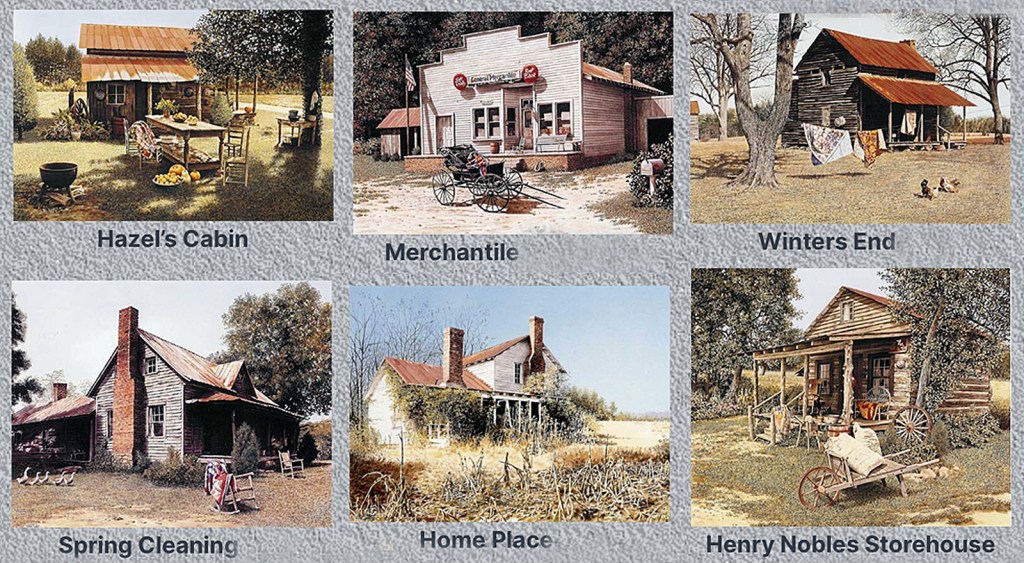

And by then, Mel had begun selling what are euphemistically called “limited edition prints” of rural scenes. These were essentially “posters” made from painted originals, printed up in volume and given evocative titles, like Down East or Wentworth Winter.

Most regions of the U.S. have some populist art tradition that sells well commercially. In Maryland, it is pictures of skipjacks on Chesapeake Bay; in Maine, it is lobstering; in Arizona, it is cactus or Indians; in Texas, cowboys. In North Carolina, it was barns. Mel painted barns and farming scenes and became known statewide for his paintings and the prints made from them.

He did well with these, enough he could buy some land in the woods outside of Reidsville, N.C., and design and build a new house and studio. And his prints were popular enough, he could begin selling not just the prints, but the original paintings.

Mel would sometimes cynically denigrate the art he was making, thinking of it as hack work. But it put food on his table and motorcycles in his garage. In retrospect, these images were better than they needed to be. They often had some edge to them, such as the print of a fox skulking near a barn, titled Thief, and presumably looking for chickens to grab.

Thief

Or, more graphically, a dead rabbit, run over in the road.

Highway 704

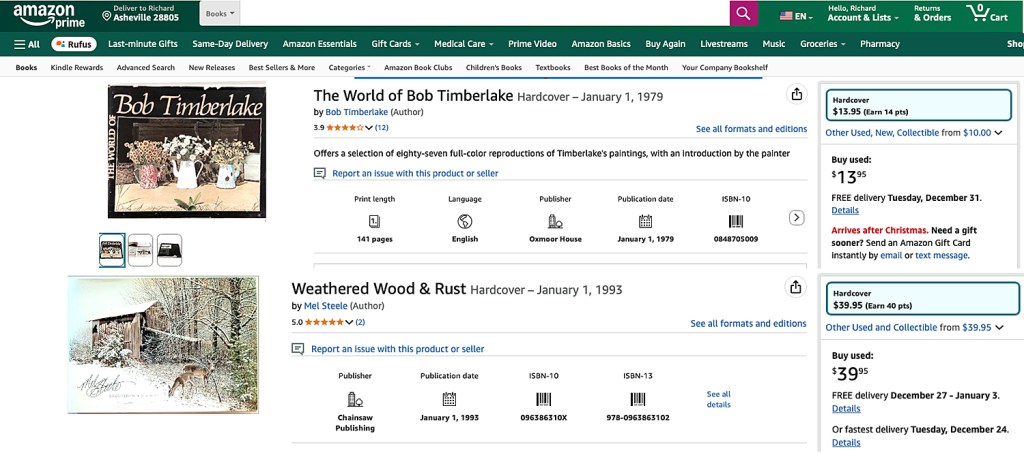

I say these prints were made better than they needed to be, and compared with many of the regional prints from around the country, they were. The most famous in North Carolina is Bob Timberlake, who has turned his talent into a marketing juggernaut, selling prints and furniture from his gallery in Lexington, N.C. But compared with Mel’s paintings, Timberlake’s are simplified and verge on the cartoonish. And they traffic in a greeting-card sort of nostalgia.

“Boyd’s Creek” Bob Timberlake

There is a long tradition of such sentimental fluff. People have always longed for a past they remember as better than it was. Victorian genre painting is full of such stuff. And artists, such as Paul Detlefsen, made a career out of sentimental Americana, painted for calendars and nowadays reproduced on jigsaw puzzles. Happy ragamuffin farmboys with fishin’ poles, covered bridges, horse-drawn wagons.

By Paul Detlefsen

The point is, the artists who make these images never actually lived such lives — Detlefsen was born in Denmark. It is a fictional history they proffer, a mythologized lie.

“Old School On the Hill” P. Buckley Moss

I don’t know if P. Buckley Moss had any real talent — she didn’t really need it for the kind of work she did, cartoonish prints of Mennonite farmers in northern Virginia — but Mel put some solid effort into his prints.

Of course such prints all play on a kind of sentimental nostalgia, but the nostalgia in Mel’s prints is earned: He and his sister did live for a while in a log cabin growing up. They did know the houses and barns that show up in his prints. And rather than knock off simplified versions, he worked hard on detail and finish.

“The Thicket’s Edge” Mel Steele

Not that there wasn’t some tacky marketing involved. Mel knew his audience and often played to them. When he thought he could sell three prints instead of a single one, he tried making “trilogies,” such as the “Quilt Trilogy” — three prints featuring old-timey quilts in them.

Or, discovering that he could charge more if his prints were “remarqued” — that is, a small detail from the image could be repainted in miniature on the border in actual paint — he began doing just that. You got a tiny bit of genuine painting along with your photomechanical print of the main picture. There should be no forgetting this was a commercial endeavor.

Timberlake had published a coffee-table book to market his prints and Mel did the same, in a 1993 book called Weathered Wood & Rust. The text is godawful and smarmy — they hired a writer to come up with some cliché-filled pabulum — but the images were beautifully made.

Marketing was an essential part of the limited-edition print business. But such things could get out of hand. I remember visiting the Moss studio in Virginia and seeing a framed print for sale with added “value” for having three signatures. First, on the original painting, which was then photographed and printed in large-number editions, with each prints given a second signature. And third, after the prints was framed, the glass was given an extra John Hancock, with gold ink. I don’t remember Mel ever going that far.

I’ve spent a long time on this part of Mel’s career. I believe he often felt sheepish about courting popular fandom when what he was really interested in was more serious art. I have been telling him for years that he has nothing to be ashamed of for those populist prints. They really were often so much better than they needed to be.

I’ve pointed out that his subjects, while they may have had an aura of nostalgia about them, were nevertheless genuine to his life and upbringing. I believe he felt genuine emotion toward them — even if he might have expressed a knowing disdain for what might have been taken as “cornball.” His professional training led him in one direction; his life experience informed another.

I want to discuss two prints in particular. The first is Mitchell’s Mercantile, a gouache from 1980, that is just an old chair on a store’s front porch.

Mitchell’s Mercantile

One of the things you notice in Bob Timberlake’s prints is their general lack of shadow. They are “cartoonish” in the sense that their subjects are simplified and usually portrayed in an overall wash of light. In Mel’s pictures, real objects tend to throw real shadows. Also, in the popular prints of other artists, objects — buildings, people, animals — are generalized, sketchy and not particular. But this chair on this porch is not just a chair, it is this chair. It is almost photographic; Mel has spent time and effort to look and to pay attention to the world. This is not some generalized metal chair.

Paying attention is the unacknowledged secret of fine art. That is true of abstract art as well as naturalistic art. Nothing is glossed over or ignored. And so, the very exact angle that the chair’s seat leans back is paid attention to. The quotidian is afforded dignity. It is the idea behind the German expression “Ding an Sich.” The Thing in Itself.

One does not need to get all academic over it. But look at the chair, the wood floor, the rusted Coke sign and the light that plays out over it all, from a distinct direction and shaping the images and recognize that Mel Steele has looked with care and internalized each millimeter of his picture.

The other print is my favorite of all of them, and that is for entirely personal reasons. When Carole and I moved in together in the early 1980s, we lived in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, along the New River in Ashe County and many of the hills were cleared for cattle, and other hills were natural “balds.”

West Jefferson

Mel made a painting of this bare and unprepossessing landscape. It resonated strongly for me. I know this landscape and no one I know has better caught its sense of isolation and innigkeit — of being alone in an expansive space. I am convinced Mel made this picture because he felt something genuine in it. Surely it could never have been one of his more popular sellers. (In fact, Deborah tells me it was never made for sale, but as a Christmas gift for several valued regular collectors of his work.)

So, there are two directions I sense Mel has always been pulled in. On one hand, as a professional and commercial artist, he knows his public and is able to aim his work at that market. But on the other hand, he truly wants to make something worth more than mere dollars, and so even making commercial work, puts an extra effort into it — and something personal — that lifts it above its mere purpose.

I shouldn’t overstate my case here. Mel has made his share of purely pandering images, and often they are not as well crafted, and maybe a little more quickly tossed off. The buying public is looking for rural nostalgia and Mel could give it to them. But in his best prints, he has invested himself and his life experience.

His success in the print world meant that he could also sell original paintings in art galleries, and accept commissions. And he made quite a few paintings for himself. Landscapes,

still lifes,

portraits

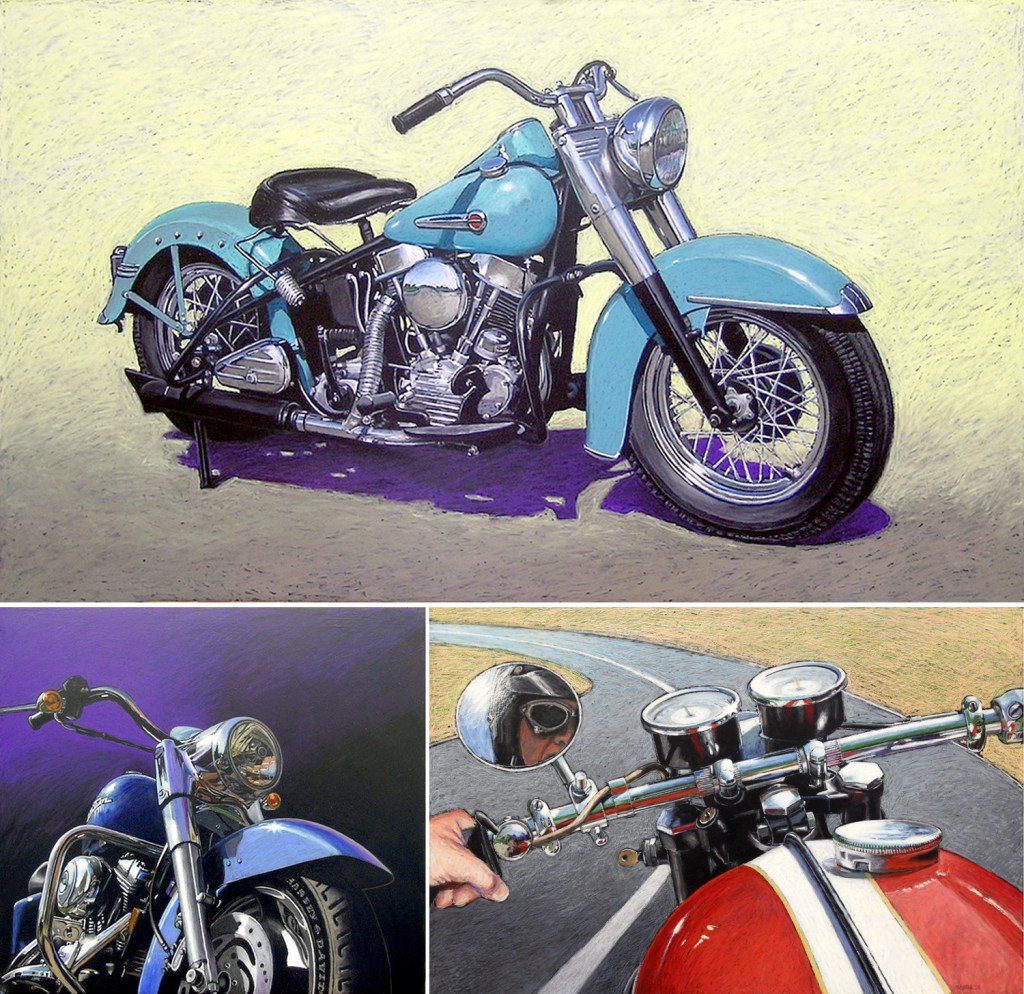

— even the motorcycles he loved and collected (he had been a big motocross fan as a young man

Which showed up in a series of motorcycle paintings

He experimented with a series of paintings made from little squares with letters, numbers of text in them, such as the red pepper. A detail shows how the picture is made up of tiny glyphs.

He made another series of copies of famous paintings, usually in oil crayon, but always he made little “improvements” in them (as he called them), like this copy of Edward Hopper’s Chop Suey.

Mel could take on any style of art. His popular prints were photorealistic. But he could also do impressionistic

Or primitive

Or design work

Or even sculpture

Mel can tackle pretty much any style or genre. Yet, what he really wanted to do, since his early days at art school, was the abstract painting he discovered there.

It sometimes needs to be pointed out that abstract painting isn’t necessarily easier or faster than detailed realism. In fact, quality in any variety of art depends on careful attention to color, line, design, mass, balance, and a sense of depth (or lack of, when that is the point). A successful photo-realist scene will only work as art if all its parts work in harmony. A good abstract painting is the same as a good realistic painting, except without a subject matter you can name — like a barn or owl.

Believe me, as an art critic (often asked to judge local art shows and give out blue ribbons), I saw a deplorable boatload of bad abstract painting, and almost always, the problem was that the artist really just threw some colors on the canvas in a haphazard fashion. Bad abstract art is a dime-a-dozen.

Bad, indifferent, tossed haphazardly

It isn’t just the public, but too often the artists themselves, that think an abstract is made by energetically slathering paint on the canvas, and that the energy of its creation will be conveyed to the appreciative viewer. Das ist schlamperei. Sloppy; lazy; careless.

Sometimes a painting can give the appearance of spontaneity, but such doesn’t happen through accident. One may look at an abstract painting by Mel’s hero, Willem de Kooning, and believe he tosses them off in a fit of athletic frenzy, but there is film of the artist painting and mostly he stands back from his easel by about 10 feet and looks at the canvas for two or three minutes and then approaches with his brush and adds a few strokes and steps back again to look. It is a slow accumulation of careful decisions made through a lot of just looking and thinking.

I have watched paintings by Mel in the process of being “builded.” He likes to work alone, but I have snuck into his studio in off hours and seen paintings change slowly over days until he gets the final version he is happy with. Whole quarters of the canvas may be covered over and repainted; new details added or others scrubbed out.

Subtle differences in three states of the same work

When the famous Japanese Ikiyo-e artist, Hokusai, turned 80 he said, “I have drawn things since I was six. All that I made before the age of 65 is not worth counting. At 73, I began to understand the true construction of animals, plants, trees, birds, fishes, and insects. At 90 I will enter into the secret of things. At 110, everything — every dot, every dash — will live.”

Mediocre artists will find a “style” and stick with it. Better artists continue to grow their whole lives. You can follow the growing maturity of Mel’s abstract work from his early canvases to his most recent.

His early abstracts suffer from the rigorous training he got at art school. His abstract paintings are notably careful, well-lined, almost as if he were making photorealist versions of abstract paintings. When architects attempt to make gallery art, they often make this sort of deracinated art — more design-y than resonant. It’s what I have always called “architect’s art.”

Even in this early work, you can see some through-lines to the later. Unlike many abstract paintings, which may as well be wall-paper, Mel tends to situate shapes against a background. Often the background is a tiny sliver at the top of the canvas, sometimes the shapes occupy a spot at the center like a vase of flowers on a table.

You see that in the early paintings and in more recent ones.

This gives Mel’s abstracts a solid sense of structure. Squiggles don’t just run off the edge of the frame.

He also uses the size of shapes and their colors to create a sense of near-and-far, a sense of depth in the painting, so you can look at it as if you were gazing at a landscape. (I don’t want to get caught up here in an argument about Clement Greenberg, the influential mid-century critic who claimed that painting should be flat and that two-dimensionality was its essential fact and that to attempt the illusion of depth was somehow anti-art. That was always pure balderdash and if he had had eyes instead of theories, he would have seen that.)

Some shapes cover up parts of other shapes. Cool colors and darker shades can recede while warmer colors and brighter ones can appear more forward. It isn’t all just a great bowl of oatmeal. There is visual structure available to those who take the time to immerse themselves in the art. Art takes time to look at and the longer you look, the more complex the painting, and the more intense the emotions that may be evoked.

I mentioned that in his more commercial prints, at least in the best of them, Mel found ways to put his own life into them. Unlike some popular print artists, who present a nostalgic world that never actually existed, Mel’s barns and farm houses are part of the life he’s actually lived — at least in his childhood, and after a city life in Charlotte, once again in his life back in rural Rockingham County.

When I have gone to visit Mel and Deborah in Reidsville, as I drive north from Winston-Salem on U.S. 158, I pass many tobacco barns like the ones in his prints. They are still there, and there is often a damaged barbed-wire fence around them. Nostalgia-mongers love white picket fences; there’s little quite so warm and fuzzy about barbed wire. Yet, it’s that detail that makes Mel’s print carry a weight greeting-card art never even attempts.

Softer art likes flowers; Mel’s best paintings show weeds.

And I think there is something similar in the abstract paintings. In most of them, there is a recurring detail of zebra stripes. A shape, either large or small, will be crossed with black-and-white stripes. I’ve asked Mel why and he doesn’t have a thought-out answer. “I just like it,” he says. But Mel grew up in a house in Madison, N.C., just across the street from a railroad grade crossing. I suspect that this detail has lodged in his consciousness and shows up as an emotional nexus in work that is otherwise non-figurative.

After all, the front door of his studio-home is striped also, and a spooky mask that sits on his wall. You can find these stripes all around his house, including on throw pillows on his sofa.

Like many creative people, Mel doesn’t seem to want to look too deeply into, or talk about the wellsprings of his work. Many artists I’ve talked to are afraid if they look too closely, their inspiration might dry up.

One should always be wary of claiming to know what is going on in another person’s noggin. And I may have completely misunderstood Mel’s muse. If so, I’m sorry. It is only a guess, from watching from the outside.

But over a very long work life, Mel has seemed to avoid talking about anything too deep in his art, while at the same time putting great effort into its making, even when less care would have been enough.

For the past dozen years or so, Mel has painted landscapes on commission for certain collectors, mostly sold through his agent, and painted canvas after canvas working on his abstracts, using patches of color, on top or beneath each other, as if they were landscape paintings of imaginary shapes rather than trees and streams.

You can see the layout of shapes running through the middle of these canvases, with a clear patch — almost a sky — above and another patch, almost like a meadow, below. The fact that the middle is made up of a bustle of shapes and colors might stand in for a forest — except that they don’t need to. It is sufficient that they are tangible shapes.

It is the way some classical music has a “program” that tells you the story being depicted in the orchestra, but if you didn’t know the program, you would still be able to feel the movement of the music in a specific direction.

It is in this sense that I say Mel’s abstracts can be seen as quasi landscapes. Not that they are meant to be literally so, but that they display a visual form that mimics the mental idea we have of a landscape. Take away anything in a scene that has a name and this is what is left. Color, shape, form, space, frame.

I have included a passel of Mel’s artwork in the blog entry, but I have at least another 200 images I simply don’t have room for. Mel has been an extraordinarily prolific and various artist, using many styles and many media over the years — gouache, oil crayon, acrylic, pen-and-ink. There is almost no style, genre or medium he has not taken on over the past 60 years.

He is better than he lets on.

Click any image to enlarge