If you’re reading this, and read blogs, it suggests you are a reader, and probably love books as much as I do. In fact, you may be a bookaholic, or have gone over the edge to become a bibliopath. Books are a central foundation of who I am, who I used to be and who I am still becaming. How can it be otherwise for anyone with a pennyweight of curiosity about people and about the world?

I’ve written about books in my life in many blog entries, and one of the most often-read is the piece I posted on Oct. 10, 2020, called “Shelf life,” in which I chose a single rung of a bookshelf in the house and discussed all the volumes resting on it. We are, at least in part, what we read: The books become internalized. And so, as I wrote then, I wanted: “to search for myself among my books.” I decided to take a single shelf from a single bookcase, “to see if they were in any way a mirror in which I could discover my own physiognomy.”

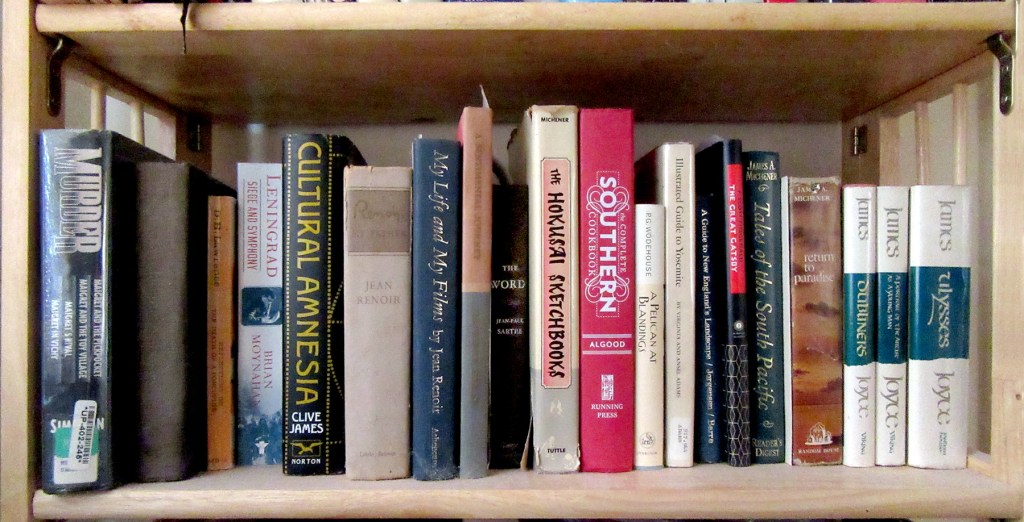

I didn’t want to pick a neatly organized shelf, but one where books were randomly scattered, left uncatalogued after casually unpacking after a move, or after re-reading, or just was too lazy to put back where it made sense. The bookcase next to the bed seemed the proper choice.

And so, I thought I might do so a second time. I looked at the shelf above the one I wrote about and it also seemed to be a mirror: That was me, there, in those pages, however jumbled it seemed to be.

What surprised me the most was how many of these books have been with me for most of my life — books I read when young that still take up space in my brain and on my shelf. And also how many were only recently bought and opened.

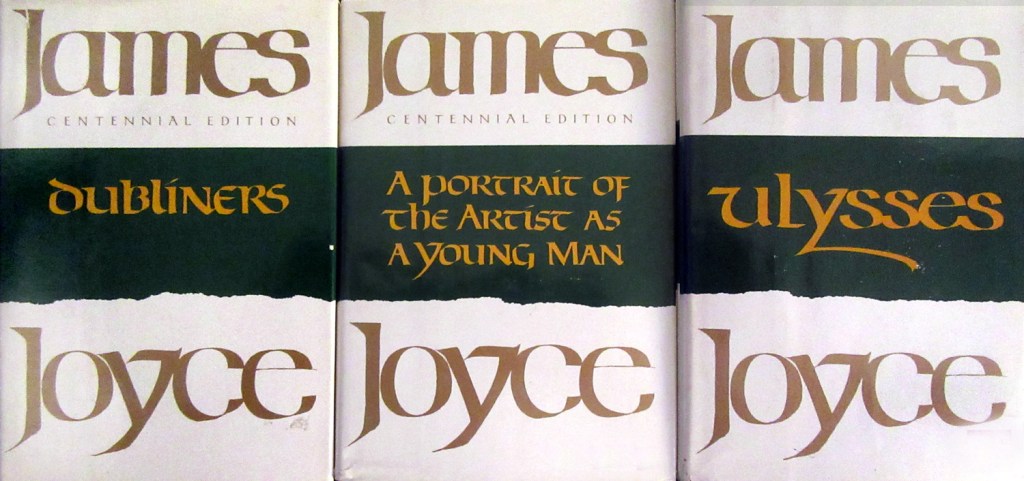

I should start with the three matched volumes at the right of the shelf: James Joyce’s Dubliners, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and Ulysses. This handsome set replaced the many earlier versions I have owned in various editions. (I still have at least four other Ulysses on various shelves in the house, including a very special cheapie pirated paperback printed by Collectors Publications, a publisher most known for printing porn — which I suppose Ulysses was thought of when this version was published — ads at the back of the book offer The Incestual Triangle, Four Way Swappers, and All Male Nudes, among other things.)

I first read Portrait of the Artist when I was in eighth grade, in the dark green paperback Viking Compass Book edition. I’m not sure how much I could have comprehended reading it at the age of 13, but I knew I loved the way the words looked and sounded: “Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo …” There was the mud of the rugby field, the great hellfire of the sermon, and the “forged in the smithy of my soul.”

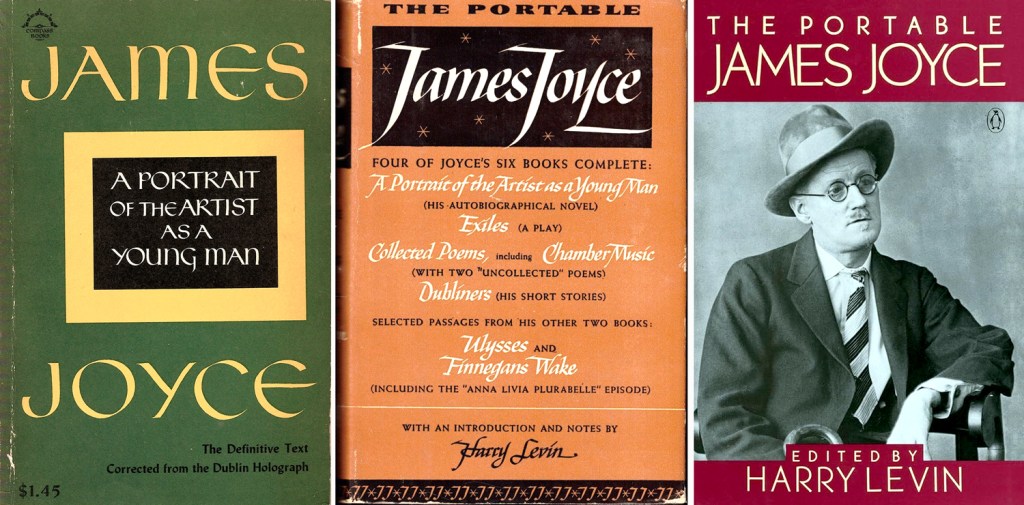

I reread the book every four or five years, and every time, it hits the spot. In the habit readers always have, I soon jumped on all the other Joyce I could find. I bought a copy of Viking’s A Portable James Joyce, and have given up or lost several versions over the years, but still have one, a hardcover one, now in a library binding — in fact, it sits on a lower shelf of this selfsame bookcase I’m writing about. I tackled the play, the poetry, Stephen Hero, the essays — even Finnegan, although, at the age of 76, I am still defeated by the whirl of the whorl of the world of Finnegan. I will leave it to the next life.

Ulysses was a harder nut to crack after Dubliners, when I was a scrub-faced kid; Ulysses problems were verbal; Dubliners was harder to understand because of the complexity of the human emotions written about. You have to have some life pushing behind you to grasp the complexities of human experience and emotions written about in those short stories. As a teenager, I knew pimples better than I knew people. I re-read Dubliners last year and was blown away, especially by the final “The Dead.” It broke my heart.

Ulysses I did get into years later, and it is now my favorite novel of all, although, to be fair, I don’t always read it cover to cover, but rather, read again and again the bits that I most love. It astounds me: It is filled with some of the most beautiful prose I have ever encountered. No, I take that back: The most beautiful prose.

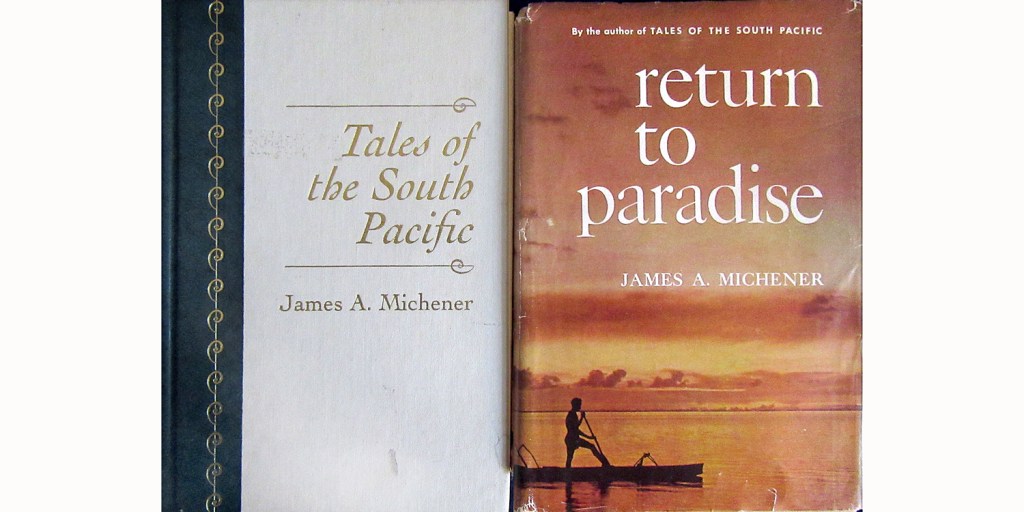

Next to Joyce on the shelf is James Michener: Tales of the South Pacific, and Return to Paradise. I remember, in my 30s and still something of a snob, looking down my nose at Michener as a best-selling author of doorstop bricks. But one day, in a book store, I picked up a copy of Tales and thought I would read a page, maybe two, to catch the flavor of Michener’s prose. It was 30 pages later I was standing there ready to flip the next page. This was a special kind of talent: to make you need to find out “what happens next.”

The prose was simply not the point. It was invisible; you read through the words as if looking through glass. This was story-telling, and Michener really has a value I had failed to understand. I’m not saying he didn’t eventually turn into an industrial manufactory, but in his first book, he made magic. It was also nothing like the South Pacific musical I had expected. Rather it gave me a real sense of what the war in the Pacific must have been like for those who experienced it.

A few years ago, after re-reading it, I found a copy of its sequel, Return to Paradise. I got through a few of the stories, maybe a third of the way in, but lost interest. The magic had gone. It was OK — it wasn’t just junk — but it didn’t grab me the way the first book did. It was more like a book of short stories that a short story writer might write. Something, perhaps, that a publisher might request after a best-seller. The two sit together on the shelf nonetheless.

I’m going out of sequence on the shelf to mention the other Michener book sitting there. In 1958, Michener published The Hokusai Sketch-Books: Selections from the Manga. Hokusai, of course, was the famous Japanese 18th-19th century artist. In 1814, he published a multi-volume sketchbook, called manga, in which he drew everything he saw in the world around him: people, plants, animals, ghosts, architecture. It was an encyclopedic venture. Michener selected enough of these drawings to fill out a thick book. I have owned it since college. It is one of my holy-of-holies.

From high-school days, I was fascinated with all things Asian; I read books on Zen Buddhism, listened to Noh Plays, took my girlfriend to restaurants with hibachis. There were Kurosawa movies and sumi ink paintings, which I attempted with my own shizuri and brush.

The non-Western way of looking at the world opened my world view and I have been looking beyond the horizon ever since.

Next on the shelf some The Great Gatsby and nothing proves how little youth knows, than what I made of the book — or didn’t make of it — when I was required to read it in eighth grade. I never then figured out who this Gatsby guy was; I thought the book was about Nick Carraway; and what the heck was all that about green light?

It’s not that I didn’t enjoy the book then, but that I had no clue about its depths. I bought an excellent edition three years ago and reread it for maybe the third or fourth time and loved every second of it. It is a deep, rich book, with prose that is delectable.

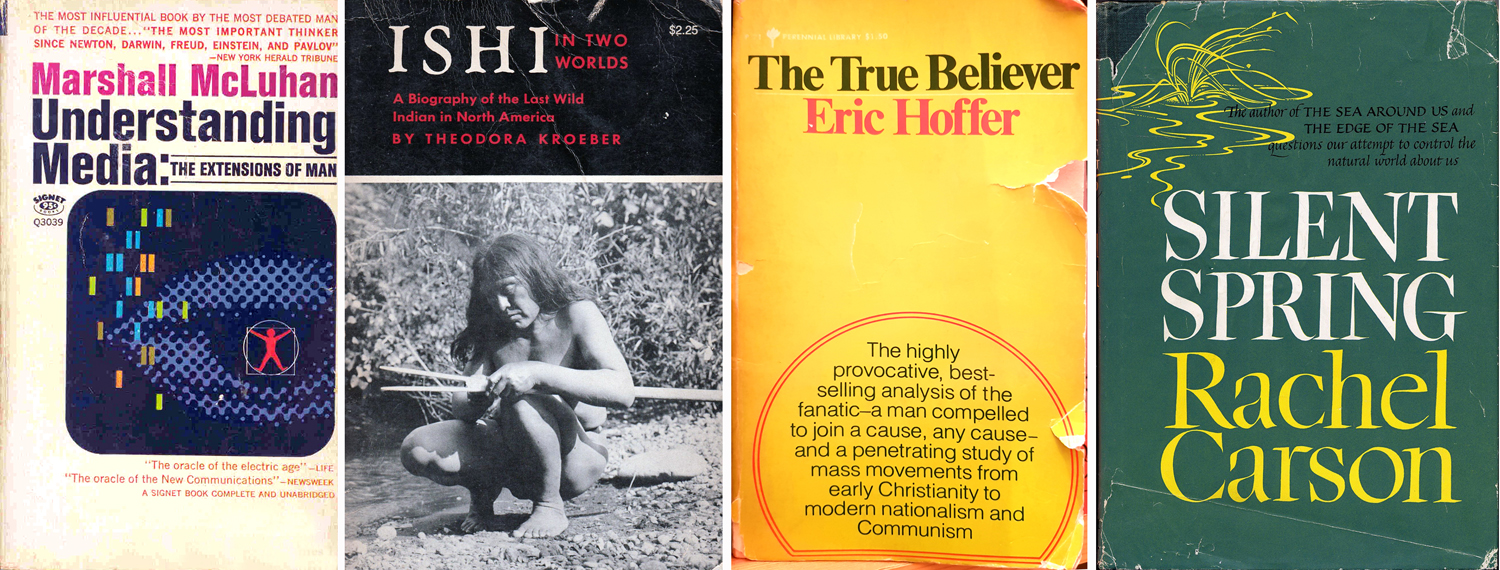

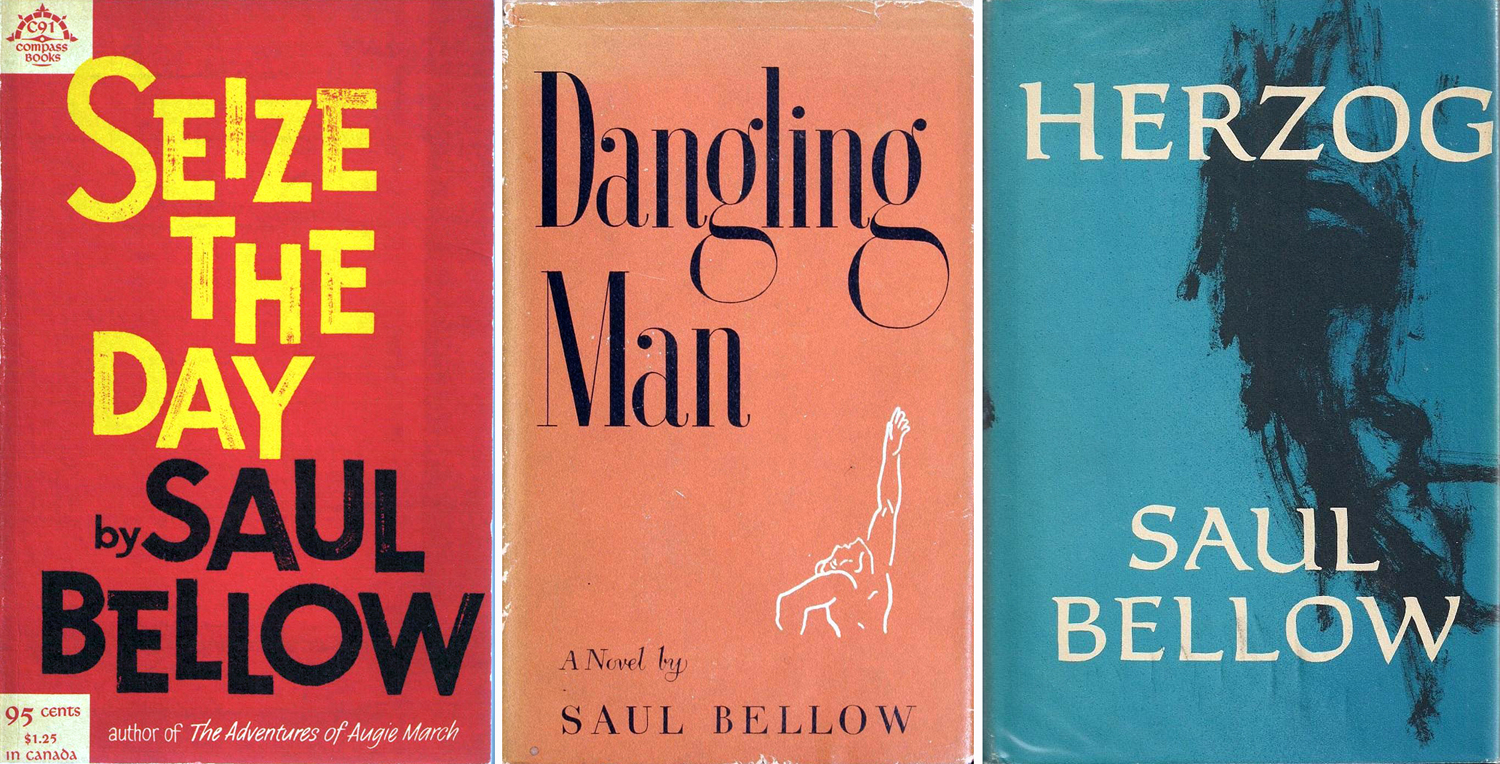

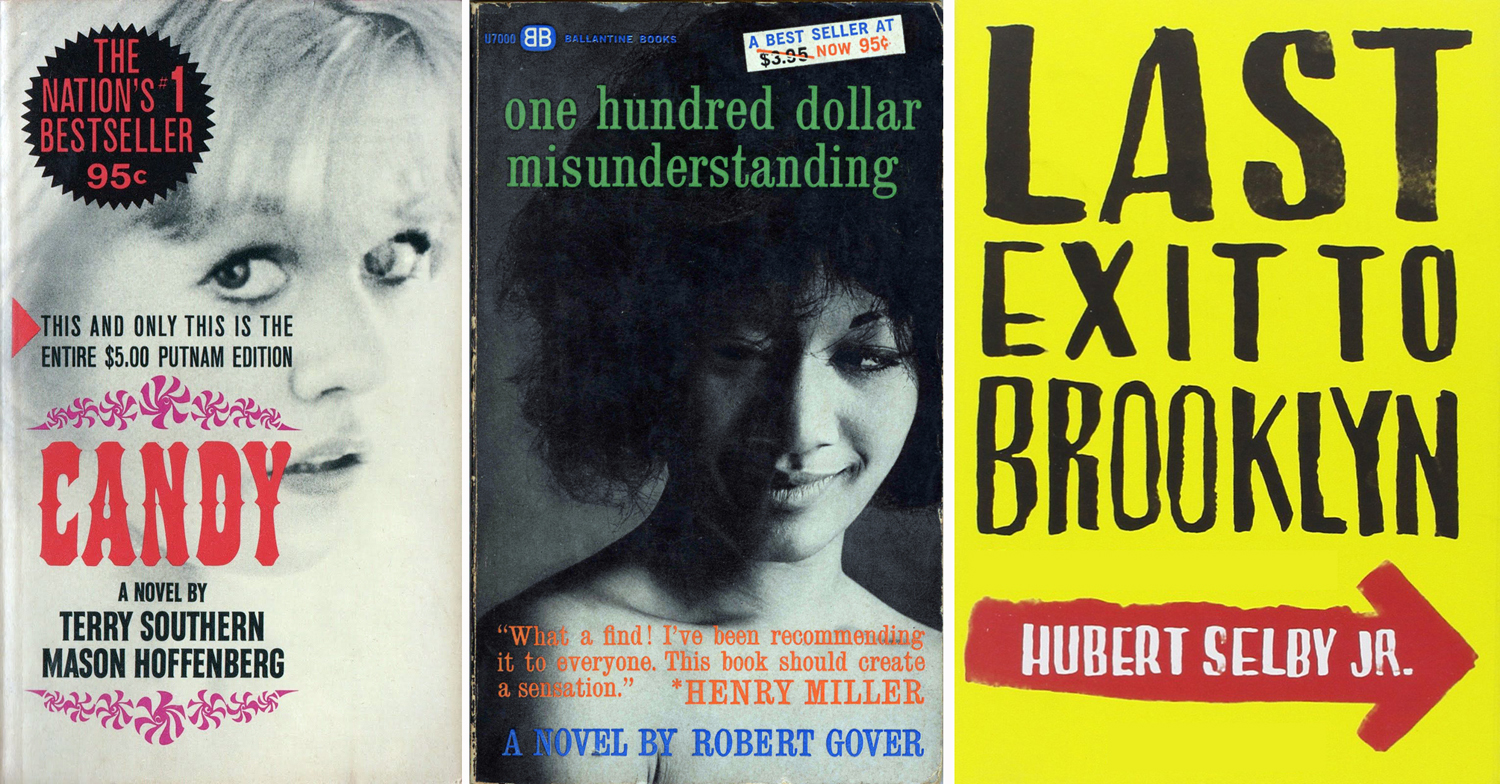

I believe for most young readers with a ripe curiosity, we tend to want to read beyond our abilities. We believe, as teenagers, we are grown-ups and want to partake of the adult world. And so we — and I — took to reading much that we had no business attempting. I read Saul Bellow, Henry Miller, John Updike, Jack Kerouac, Thomas Pynchon, James Purdy — a whole host of writers that I thought proved I was now in the company of the heavyweights.

And among those books was Jean Paul Sartre’s The Words, his autobiography. I knew he was an existentialist and that all the most intellectual people (this was the mid-1960s) were hot on existentialism. Not that I knew what that meant (I’m not sure anyone really does — it encompasses so many different things, but back then, it pretty much meant berets and espresso). But I read it, enjoyed it, thought I understood it, and flashed a few words around to let anyone know. I got a subscription to Les Temps Moderne, although I couldn’t read French (and also a subscription to The Evergreen Review — I was one hip 16-year-old). I re-read Les Mots last year and it’s a fine enough autobiography, but not exactly world-shaking.

Getting back on track along the bookshelf: In the 1970s, I was living with a redhead and we wanted to travel. We hiked a good portion of the Appalachian Trail, and drove, amongst other destinations, to Maine and New England. I was fascinated by geology and I had a book by Neil Jorgensen called A Guide to New England’s Landscape. I had by then, an interest in all things under the heading of “Nature.” I had a raft of Peterson Guides, could name dozens of plants and birds by their scientific names (“Know-atia Dudiflorum,” my wife teased me), collected rock samples, and could name dozens of constellations in the night sky.

The Jorgensen book accompanied us as we drove past monadnocks and till, varved clays and drumlins. I admit I haven’t read the book since then, but I still have it, as a memento of meaningful times.

I was by then active a photographer, and so I had another guidebook: Illustrated Guide to Yosemite, by Ansel Adams and his wife, Virginia Best Adams. I so wanted to visit Yosemite, but never had at those years the time or money for such a long trip. The book is loaded with Adams images, and so, it functioned more as a picture book than a useful guide. It was only many years later that my wife and I drove up the east slope of the Sierra Nevada along the Tioga Road and got to see the stunning Valley. The book is another that I’ve owned for 50 years and is a piece of me.

If I could choose to write like anyone, it would be James Joyce, but if I couldn’t have that, I would want to write like P.G. Wodehouse. He is magic with words, although of a more comic variety. I have bunches of Wodehouse lying around, but three years ago, I bought a new edition of A Pelican at Blandings, mostly because these new hardback versions, by Overlook Press, were so seductively handsome. If I had the money, I would buy all the volumes in this set, but this one will have to do.

All the Blandings books are a hoot. He may be most famous for his Jeeves stories, but I like Lord Emsworth and his pig and his sister Connie, just as much as Jeeves and Wooster. This is the kind of book I read when I just want to have fun.

The Complete Southern Cookbook, by Tammy Algood is not one I bought. It was a gift from my daughter. I seldom use cookbooks. And when I do want one to check on some Southern specialty, I head for the old standby, Henrietta Dull’s Southern Cooking, originally published in 1928.

I was born in New Jersey, but left there when I was 17. I’ve lived in four corners of the country, with 25 years in Arizona, and a year in Seattle, but the longest soujourn has been in the South, in North Carolina and Virginia, where my years add up to 33. I feel like an adopted Southerner.

And while I still miss the foods I grew up with, such as a good pastrami on rye, real pizza, or a kaiser roll, I have to admit that I’ve come to love those things a Yankee will never understand, like greens, pulled pork, or fried okra. I count on Mrs. Dull for those (although, to be honest, no one uses a recipe for such things).

The funniest book I have ever read is Laurence Sterne’s Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. It is one of the few I find myself actually laughing out loud at. So, thought I, perhaps his other book, A Sentimental Journey, must we worth looking into. It is much more straightforward, less surreal, and while it has its moments, doesn’t quite catch fire for me. The edition I have is however quite handsome to look at.

The next two books are by Jean Renoir. Renoir is probably my favorite filmmaker. His films are so genuinely humane and wise. Nick Carraway, from Gatsby, relays that his father gave him advice to live by: “Remember that not everyone has had the advantages you have had.” That’s all well and fine, but the words that most illuminate my life are from Renoir’s Rules of the Game, when Octave, played by Renoir himself, says “The awful thing about life is this: Everybody has their reasons.” It isn’t usually malice or conspiracy that mucks things up, but rather, “Everybody has their reasons.” You learn to be less judgmental from that.

He wrote about his work in My Life and My Films, from 1974. It is filled with anecdotes and pictures, and the quiet acceptance that is the core of his being. But even better is the biography he wrote about his father, Renoir. I was never a big fan of Pierre-Auguste Renoir. I find his paintings a little blowsy. He is the least of the major Impressionists. But, as his son writes about him, he comes off as one of the kindest, sweetest, most understanding and generous of men. I came to love old Pierre-Auguste not through his art, but through his biography.

I said we readers have a tendency to find authors we like and then plow through the whole corpus willy-nilly. About five years ago, I came across Clive James, the late Australian-English writer and critic. I tore through everything, including his poetry. And when I found his book Cultural Amnesia, I couldn’t stop myself. Subtitled Necessary Memories from History and the Arts, it makes the case that too much important history has been forgotten, ignored, or misrepresented, and that if we need an understanding of the past to navigate the future, then the men and women he writes about in this book, deserve to be remembered.

He writes about more than a hundred of them, in alphabetic order from Anna Akhmatova to Stephan Zweig. Some are hardly obscure, like Charlie Chaplin or Leo Tolstoy, but he brings to mind aspects that may have more cultural impact than you might remember, or other facets to their work.

I love the grim joy of Dimitri Shostakovich; his music speaks volumes about misery and dictatorship. His Seventh Symphony, the “Leningrad Symphony” was partly written and later first performed in that city during the 900-day siege by the German Wehrmacht during World War II. It is a sprawling work, lasting well over an hour, and its first movement has a grinding passacaglia representing the jackboots of oppression.

My wife gave me a copy of Leningrad: Siege and Symphony, subtitled “The Story of the Great City Terrorized by Stalin, Starved by Hitler, Immortalized by Shostakovich,” by Brian Moynahan. Its well-researched 500 pages cover everything one needs to know about the siege, the horrors, and its legacy. But, I confess, I have not read it. It sits there on the shelf, waiting. But I really feel I am told everything I need to by the music itself.

I went through a D.H. Lawrence period, where I read everything I could get my hands on. But not the novels or short stories. For some reason, they never much appealed to me. But his essays and travel writing, and his poetry, I adored. It’s the best travel writing I know, partly because it isn’t the usual version of the kind, but his personal, very idiosyncratic way of looking at the world.

Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine is an anthology of seven of his essays, including the title piece, which starts as thoughts on having to shoot a porcupine on his New Mexico ranch, and goes through the issue of all life dependent on devouring other life, and ends, in a disturbing turn that, for him, justifies “superior” existence having its way with “inferior.” Lawrence is capable of a good deal of piffle.

But it is the particularity of his observation that I love, the detail. Even crazy talk can be well written.

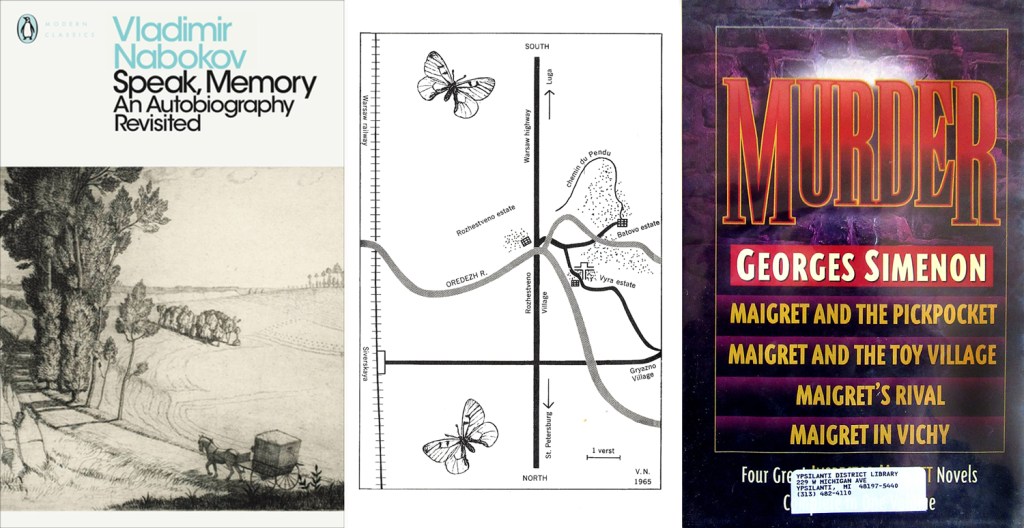

Next, the best writing, the most original use of word and sentence, since, at least Joyce, was penned by Vladimir Nabokov. Lolita is an absolute brilliance, despite is subject. And so I read Speak, Memory, his 1951 autobiography, which recounts his life in Russia, before leaving in 1940.

It begins, “The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.” So, you know you are not just getting a sequence of entertaining anecdotes. The book is a dialog, essentially, between existence and memory, the memory of a pre-Revolution Russia, as recalled by a child, and then a young man.

Finally, I have an omnibus edition of four Maigret novels by Georges Simenon. I have moments when I devour Simenon like chocolate-chip cookies, one after the other. But it can get expensive buying volume on volume, one at a time. This edition, once in the collection of the Ypsilanti District Library in Michigan, was bought used on Amazon, cost less than $5 and gave me four novels. I have read three. I am holding the fourth unread so far, in order to experience the delicious anticipation of reading it.

And so, with that shelf catalogued, I look at the books and think, do I see myself in their spines, lined up? I certainly see a bit, like seeing a face through partially opened Venetian blinds. It’s me, all right, but only a bit. I look at the book case from top to bottom and see more of the rest of me. I walk down the hall and into other rooms with other bookcases and the picture fills up. The oldest books among them all speak of the boy that remains in the core, the newest of the weary old man I am now that covers it all in wrinkles. It is that “brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.”