No, classical music doesn’t all sound the same. In fact, sometimes it’s hard to find any relationship at all between the far corners of the field. What do Gregorian Chant and Karlheinz Stockhausen have in common?

When someone complains that “it all sounds the same,” you can be pretty sure that the reason is simply lack of exposure. A sample group too small to generalize from. So, I thought, as a followup to my previous blog entry about classical music, I should try to stretch the boundaries of the subject, to stretch out the definition tightly from end to end to see how far it spreads.

If you listen to the items on this catalog, you will find music so different as to be hard to assign a common category.

In the previous blog entry, I attempted to move from one suggestion to the next in the most contrasting way, from, say, Renaissance polyphony to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring — a clear jerk from one mode of hearing to the other.

This time, I hope to provide some framework to see how what we call classical music, or art music, developed over time. You may object that about half of the music comes from the 20th- and 21st-centuries, but that is only being fair: You should remember that the Rite of Spring — which is the traditional mark for the beginning of Modernism in music — is actually closer in time to the death of Haydn than it is to us today. Twentieth Century music is no longer new — it is classical.

(I’ve chosen a single piece from each of the large clumps of music history, varying both style and genre, including keyboard, chamber, vocal, choral and symphonic. From each period, I have supplemented the examples with two contrasting pieces for further listening.) Beginning with:

Vivaldi: Gloria in D Major, RV 589

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) wrote at least three settings for the Gloria, but this one is the version everyone remembers, with its chugging motoric drive and its brassy fanfares. It is built from 12 short movements split between choral numbers, solos and a duet for soprano and contralto.

Its catchy opening “one-TWO-three-four, one-TWO-three-four” with its octave leaps, returns later to unify the work. The Baroque era ran from roughly 1600 to 1750, although styles evolve slowly and overlap. It’s not like everyone stops writing one way and begins writing the new way. This piece, from 1715 lasts about 30 minutes and exemplifies the energetic forward motion of the Baroque.

Alternates:

J.S. Bach (1685-1750), The Goldberg Variations (1714), a set of 30 variations on a repeating bass line, for keyboard; and George Friedrich Handel (1685-1759), Musick for the Royal Fireworks (1749), a suite for a large band of wind instruments, for outdoor performance during a famous fireworks display meant to celebrate the end of the War of Austrian Succession. The crowd loved the music, but the fireworks caused a building to burn down, blinded a soldier and injured several others. Later performances often added strings to the wind band, with no further reported injuries.

Haydn: Quartet in D major, op. 64, no. 5 “The Lark”

It is often said that Joseph Haydn and Mozart wrote music in the classical style (roughly 1750-1828), but in fact, they created the classical style. If Haydn didn’t singlehandedly invent the symphony, he made it what we think of today; and he did the same for the string quartet — music for two violins, viola and cello.

This is music generally less cluttered or fussy than the earlier Baroque, and seeks a kind of modest tastefulness, along with, in Haydn’s case, a witty sense of humor, as in the imitation bird calls at the start of this quartet, which was written in 1790 and has the usual four movements: an opening allegro, a dance movement, a slow movement and a jaunty finale.

Alternates:

W.A. Mozart (1756-1791) Serenade No. 10 for 13 Winds in B-Flat, known as the Gran Partita (1781), which, in Peter Shaffer’s play, Amadeus, he has Antonio Salieri react by saying, “It seemed to me that I was hearing the voice of God.” Or Franz Schubert’s (1797-1828) Symphony No. 5 in B-Flat (1816), which is a really tuneful symphony built on Haydn’s model.

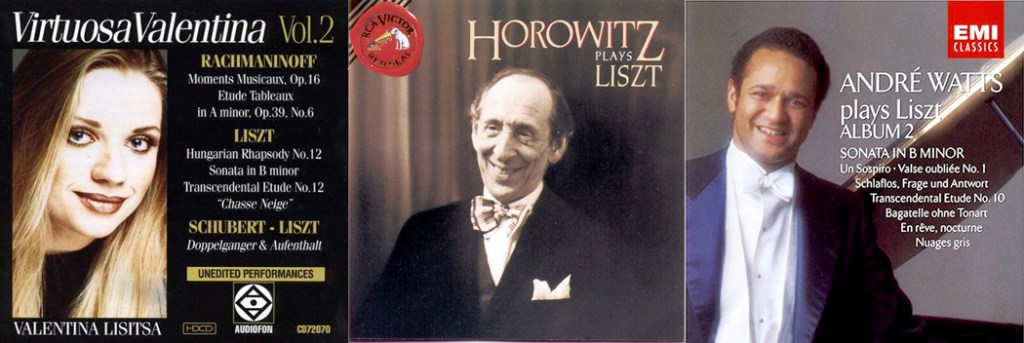

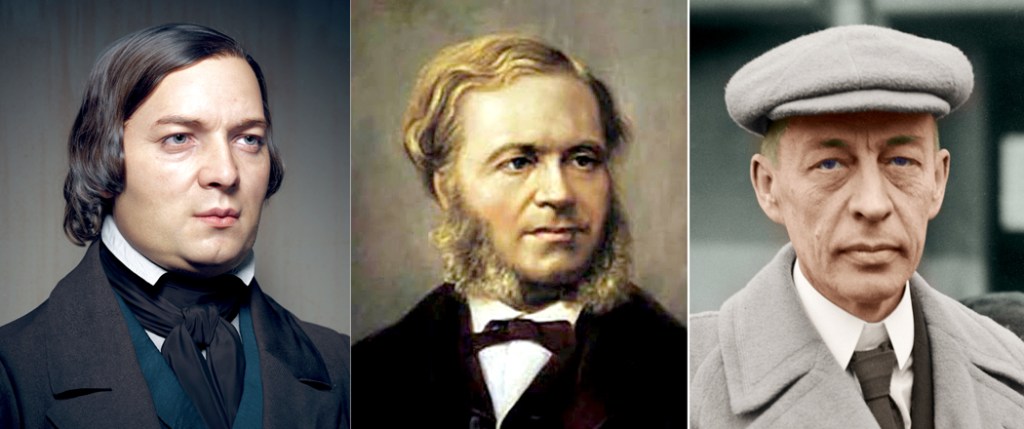

Liszt: Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-Flat

Franz Liszt (1811-1886) is the perfect Romantic composer, the greatest piano virtuoso of his time, and a matinee idol that all the ladies were in love with — something of which he took great advantage. His music, as in this 1855 concerto, is filled with all the wild emotion that the classical era avoided: over the top, loud, brash, and with a solo part for the triangle — it scandalized its first audiences. The jangle of the triangle was considered bad taste — but bad taste is the goal of much Romanticism. Audiences loved being scandalized.

Alternates:

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) wrote a cycle of songs, telling a sad love story, called the Dichterliebe, or “A Poet’s Love,” in 1840, and includes a song claiming over and over, “I’m not angry,” to some of the angriest music ever. Clever. Or Bedrich Smetana’s (1824-1884) Moldau, an orchestral portrait of the Czech river (now usually called the Vlatva or Voltava), which is a perfect example of the Romantic Nationalism that swept over Europe. Great tunes.

Debussy: Images for Piano, Book II

In the late 19th century and the 20th century before the First World War, music went through several changes. One of them is a rejection of Romantic excess, and the French composer Claude Debussy (1862-1918) came up with his own style — usually called Impressionism — of ambiguous tonality, exotic scales, and an approach to the piano that was soft and non-percussive.

He wrote a great deal of piano music, including the famous Clair de Lune, but I’m offering the three pieces in his Images, second series (1907): Cloches à travers les feuilles (“Bells through the leaves”); Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut (“And the moon descends on the temple that was”); and Poissons d’or (“Golden fish”).

Alternates:

Some composers went in the opposite direction, with larger orchestras, more chromatic harmonies of profound longing, in what is often called Late Romanticism, or Post-Romanticism. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) often added voices to his orchestral music, or wrote orchestral song cycles, such as his Songs of a Wayfarer (1885). Richard Strauss (1864-1949) used huge orchestras and explodes out of the gate with Don Juan (1889), a musical version of a Don Juan more idealistic than lecherous. It is an avalanche of sound, with a huge six-horn signature that, in live performance, you feel through you fundament as much as hear with your ear.

Janáček: Sinfonietta

Now we are ripe in the 20th Century, and Leos Janáček’s Sinfonietta (1926), a five-movement piece for huge orchestra, including 25 brass instruments. The first movement has 10 trumpets alone, playing a hair-raising fanfare.

All five movements are built from catchy tune-bits, extended and repeated. And although the music is clearly modernist, I’ve never come across anyone who didn’t instantly love the Sinfonietta.

Alternates:

French composer Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) was imprisoned by Nazis during World War II, and in prison camp, wrote his Quartet for the End of Time, for piano, clarinet, violin and cello (the instruments available in the camp). It is a hugely idiosyncratic piece, written to Messiaen’s own music theories, but can be overwhelmingly emotional in a good performance. And for the double-dip experience of atonal music, try Alban Berg’s (1885-1935) Three Pieces for Orchestra (1914), for something like what people used to call “modern music.”

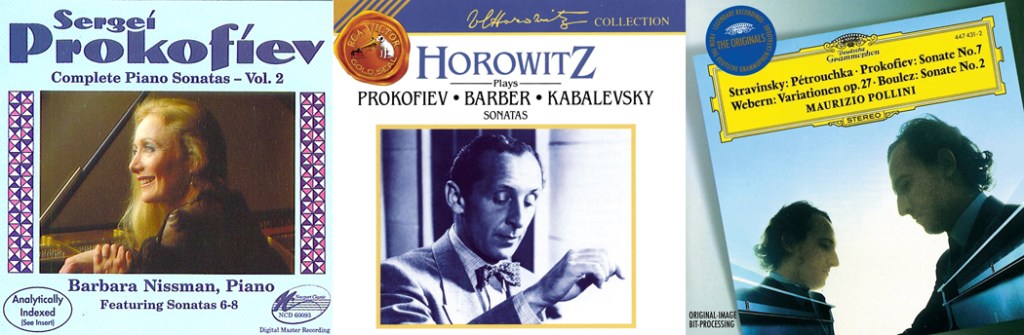

Penderecki: Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima

Classical music, or art music, is still being written, and responds to life in the current world. We live in a post-Hiroshima age, and Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki (1933-2020) summarized the feeling in his 1961 string-orchestra piece, Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima, although you may have some difficulty recognizing it as string music made by violins, violas, cellos and double basses. It shrieks of the horror.

It masses its 52 string players in tone clusters and dissonances, various vibratos and odd bowings, for 8 and a half minutes, that is not meant to be beautiful, but to evoke intense emotions. It is, nevertheless, beautiful. (Remembering Tom Robbins notion: “The ugly may be beautiful; the pretty, never.”)

Alternates:

Minimalist composer Philip Glass (b. 1937) also reacts to the modern world in his film score for the Godfrey Reggio film, Koyaanisqatsi (1982). The modern world is a crazy world, as the film and music underline, but with quite a variety of minimalist techniques. The horrors of war fill Henryk Gorecki’s (1933-2010) Third Symphony (The Symphony of Sorrowful Songs) (1976), in which a soprano sings Catholic laments and words by victims of the Nazis, all to music so slow and so inexorable as to be almost a force of nature. Its 1991 recording by the London Sinfonietta sold more than a million copies. Gorecki, surprised at the popularity of such a sorrowful piece of music said, “perhaps people find something they need in this piece of music…. something they were missing. Something, somewhere had been lost to them.”

Epilogue

Of course, this diversity is among the European tradition of art or concert music. Most cultures have their own classical musics, such as the sitar or sarod music of India, the Chinese opera music, and Japanese flute music. Each is a tradition handed down from master to student and carried forth, with development and variation. That is what makes it classical.

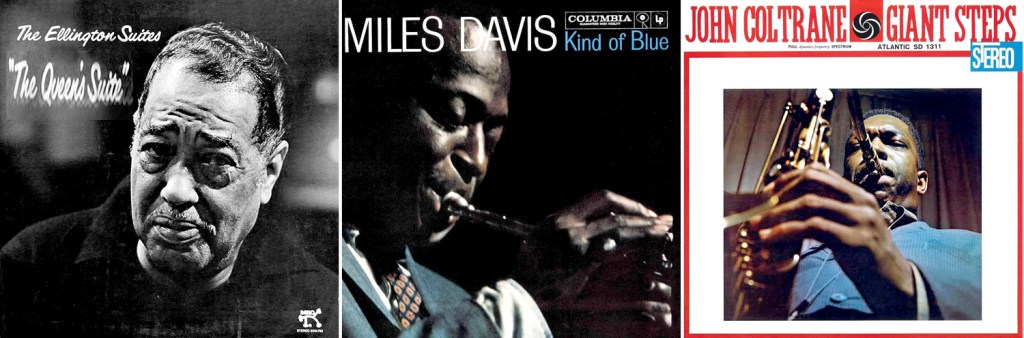

If I were to think of a purely American classical music, it would be jazz. It, likewise, has a wide range of styles and sounds, from Louis Armstrong through Duke Ellington and down through Ornette Coleman.

But it is what we call classical music in the West that I am best familiar with and love. And writing this has given me the chance to listen once more to each of the pieces I’ve written about, and more joy me.