The most distinctive feature of Shamrock, Texas, in 1980 was the old Conoco gas station downtown. I don’t know if it is still there. But that is not what I remember best about the tiny town in the Texas Panhandle.

My wife and I were driving across country for the first time. Neither of us had ever been west of the Appalachian Mountains and we had romantic ideas about the West. We dreamed of mesas and buttes, of cactus and coyotes, Navajos and the Pacific Ocean. And so we had set off in our old Chevy Citation during Carole’s summer school vacation planning to make the grand circuit. We were camping most of the way as our budget was economy size.

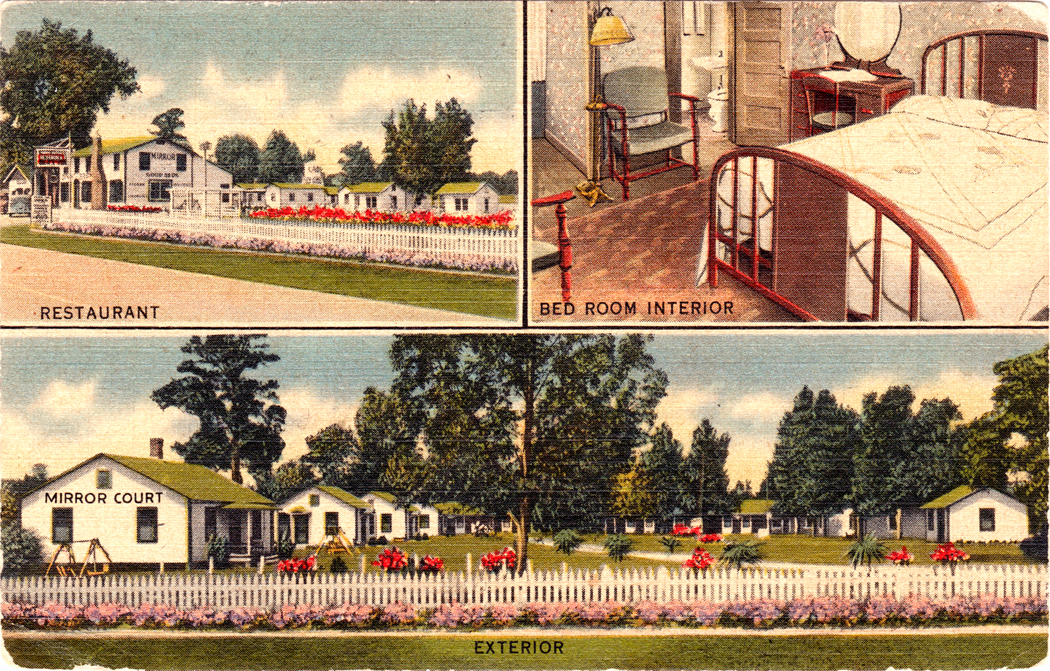

It was perhaps the third night we were out, and we found a KOA campground in Shamrock. The sites each had a concrete picnic table under a tin awning. In the center of the camp was a low brick building with the office and camp store.

As we were pitching our tent, a neighbor camper came over and told us that two days before a tornado had struck a few miles away. “No real damage,” he said. “There’s not much out there to hurt.” But he wanted to let us know, he said, because the weather forecast was iffy.

We had driven that day through some rough weather already, with dark, louring clouds, a heavy rain — the kind the windshield wipers only made mad. At one point, we had to pull off the road and wait for the heavens to calm.

But by the time we got to Shamrock, the skies were clear again. And we tucked in for the night in our sleeping bags, with the tent zipped tight and cozy.

Then, about 1 a.m., we woke to find ourselves, tent and all, floating on several inches of water. It felt very like a waterbed, except that the rain made such a racket on the tent-sides. The wind luffed the fabric and lightning grew almost constant. We both began to worry.

The only sane course of action was to leave the tent and head for the brick office. Carole went ahead of me, while I attempted to strike the tent against a howling wind. But the wind yanked it from my grip and I had to chase it until it caught on the picnic table. The tent had a tubular frame, which kept it in full shape. I grabbed the top crease and the wind took umbrage at my effrontery and tried to lift me airborne, with the tent as a kite and me as the kite tail. I fought it over my head, holding on for dear life. Finally the tent caught in the tin awning and held steady enough for me to de-tentpole the thing and collapse the kite into a smart bundle, soggy and dripping, which I put into the car before heading to the office and Carole.

The office was not very big for the 30 or 40 people herded into it. There were crying babies, frightened grown-ups. One man explained that the weather service had confirmed a tornado in the vicinity. A husband and wife were yelling at each other, each blaming the storm on the other. The wind blew outside, hurling detritus past the door. It all finally calmed down after 20 minutes or so and the wind subsided and the rain gave up its anger and turned into a normal rainshower.

But there was no way we could set the tent back up. Our campsite was a pond and the tent itself was a crumpled mess. We got into the car and thought perhaps we could make through the night sitting up.

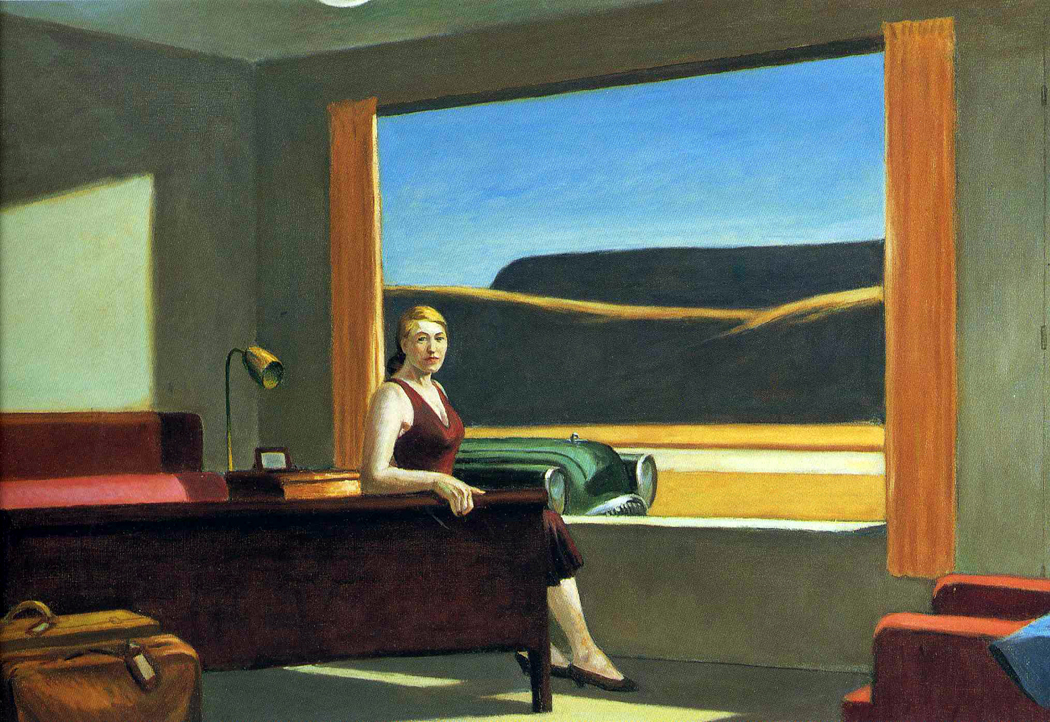

I remembered, though, we had passed a motel in town. Maybe we should drive back into Shamrock and see if we could get a room. And so we did.

When I entered the motel office — now it was well past 2 a.m. — the office was dark, but a woman came out and got us a room.

I got back in the car and told Carole, “I’m not sure about this.” The office was choked with the aroma of curry — something I normally love, but this felt more like chemical warfare. We found our room at the back of the motel complex. It had that musty smell of old cigarettes, this time mixed with the vestige of curry. The window looked out into the tool shed.

But the prize was the carpet. It was a sickly blue-green shag rug and it ran up the walls like wainscotting, and around the bottom of the bed as a kind of dust ruffle.

This would have been the worst motel experience we had, except that we had already spent a night in Forrest City, Ark., in a motel where we were bitten all night by fleas, and the toilet had a “sanitized for your protection paper band under which was a floating cigarette butt.

Still, our Shamrock motel gave us a chance to sleep and calm our nerves from the storm.

The next day, we set off west again, and finally reached Glen Rio, on the border between Texas and New Mexico, where the bottom dropped out of the flat Panhandle and we drove down into a new landscape filled with the mesas and buttes we had imagined.

We had to laugh at ourselves years later, after living in Arizona for 25 years, at the naive glee we felt at seeing the tiny, unprepossessing hills we first passed in New Mexico, which would hardly merit the notice of anyone used to such things. But they were the first hintings of the sense that the American West was entirely alien to anything we had known in tidewater Virginia, where we were living back then.

It was as if the Western movies I grew up with in New Jersey had come to life. We gawked at everything for the remainder of that first trip West, through Arizona, up California, through Oregon, Wyoming, Montana and all the states in between. We put 10,000 miles on the odometer that summer.