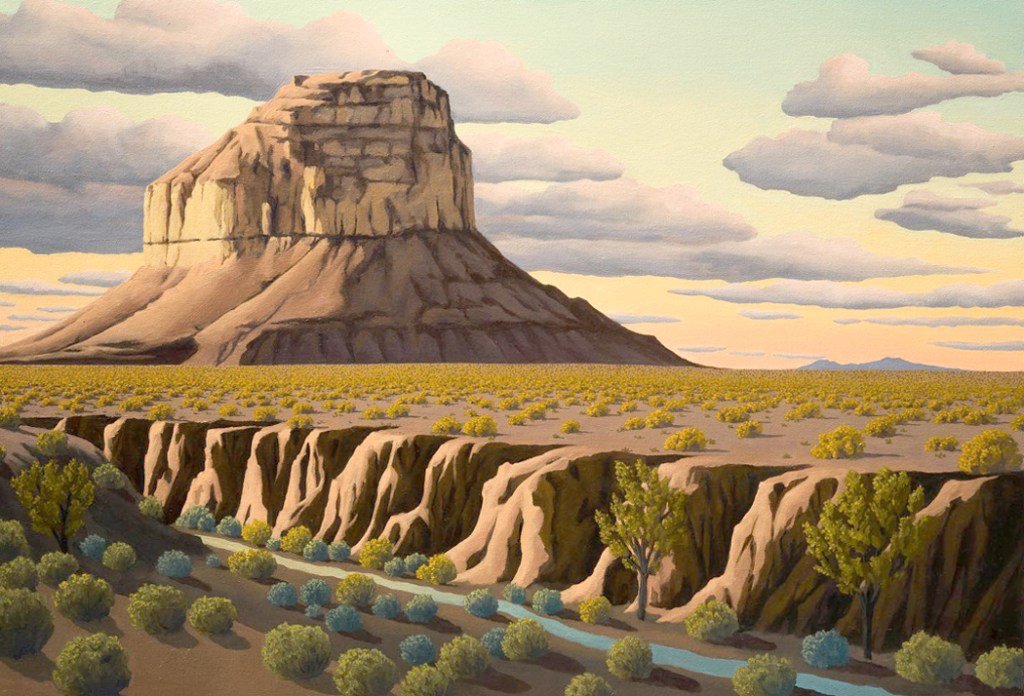

The American Southwest is the landscape of John Ford Westerns, Roadrunner cartoons and, of course George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. It is a landscape I know very well, writing about it often for The Arizona Republic when wearing my hat as travel writer. And while I can’t say I miss big-city Phoenix, I do sometimes feel quite homesick for the desert and the canyons. There is a special sense of space there, of horizons bordered not by trees or homes, but by the curve of the earth.

But there was a time before that landscape and I became intimate, when my wife and I were teachers in Virginia and first planned a summer vacation trip to the half of the country on the other side of the Mississippi River. We were unprepared, back in 1981, for what we found, having been conditioned primarily by movies, television and the occasional Arizona Highways magazine Christmas edition.

Driving west on I-40 across the Panhandle of Texas, through Amarillo, the earth was as flat as a billiard table, but at the exact border between Texas and New Mexico, the bottom dropped out of the land and the highway sloped down onto a landscape with buttes and mesas. This is the West, we thought. Finally here.

On the border between Texas and New Mexico

Carole had always been interested in Indians, and one of the goals of the trip was to visit Canyon de Chelly in the Navajo Reservation. In our Eastern ignorance, we pictured the canyon as these steep walls of rock rising up from the land on either side of us. At least, that’s what the photographs looked like.

Canyon de Chelly by Edward S. Curtis, 1904

But we had it backwards. Canyons are not cliffs rising up, but great holes dug below the surface.

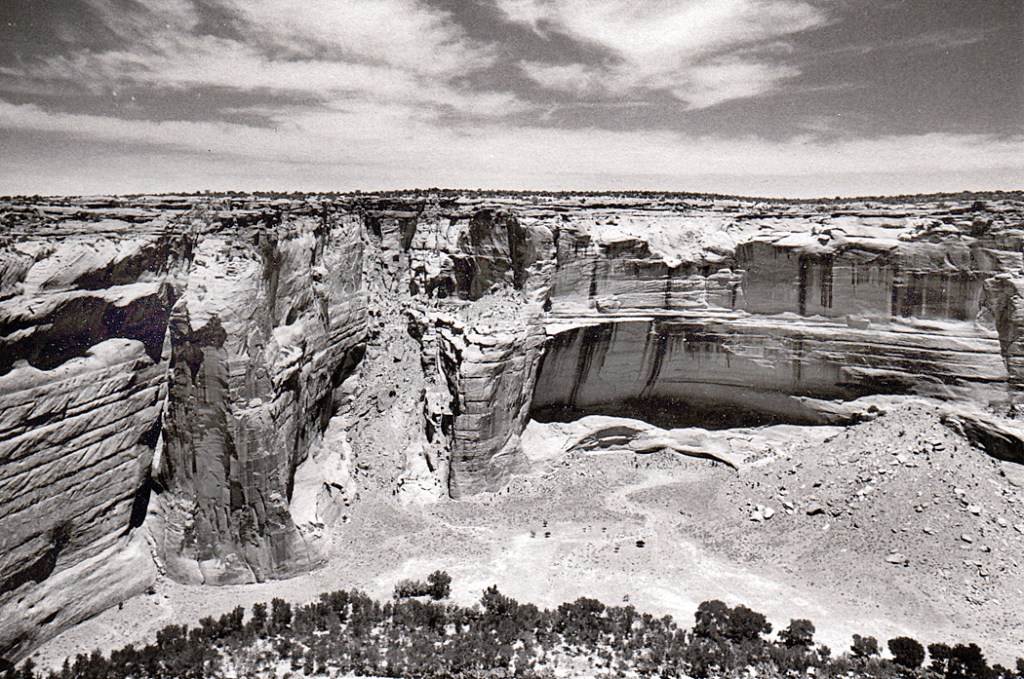

We were lucky, we approached Canyon de Chelly from the east. Most people arrive through the town of Chinle, to the immediate west of the canyon. Chinle is a tourist trap of motels and souvenirs. But coming to it, as we did, there was nothing but pine covered mountains and rocky wilderness. We drove in on an unpaved road — Navajo Route 7 through Sawmill — from New Mexico and coming up to an unmarked fork in the road, we saw a Navajo man sitting next to his pickup truck, which was piled with firewood. We asked him the way to the canyon. He said nothing but turned his head and lifted his chin to point the way. We continued down a wooded hill into a low scrub land, looking across the plain, and I noticed a darker spot in the sun-splashed land. When we pulled over and parked and walked to that spot, it was 400 feet straight down to the bottom of the canyon. It was somewhat like viewing a negative instead of a photograph: It was all backward. It was down, not up. It was Bat Canyon, one of the side shoots of Monument Canyon, one of the many side canyons to the main event.

Of course, we slapped our foreheads (figuratively), because, of course, a canyon is an empty space, not a mountain range. Later as we continued on and found Chinle, and a motel for the night, we realized also how lucky we were to have found the canyon for ourselves, and not through the tourist muck. We had that side canyon all to ourselves. We sat alone on the rim looking down into the abyss for hours, listening to the breeze and the birds, before another car even drove by.

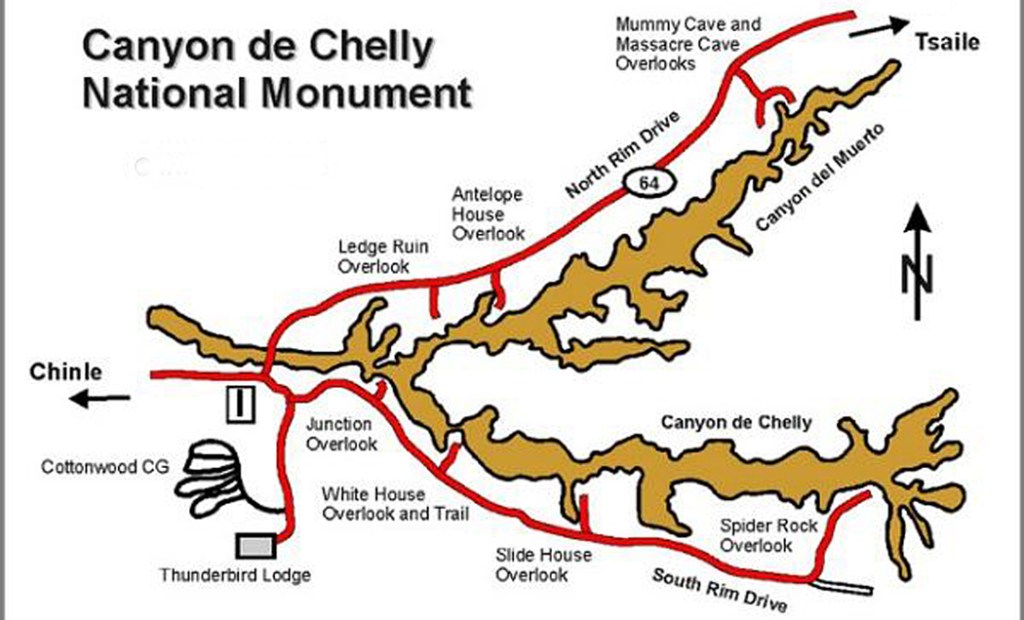

Canyon de Chelly National Monument covers 131 square miles in northeastern Arizona on the Navajo Indian Reservation. Seen from the air or on a map, it is a chicken-foot shape of multiple canyon systems that runs for about 24 miles toward the east and the Chuska Mountains.

Most tourists in Arizona head straight for the Grand Canyon, which is vastly larger and more immediately impressive. “Most famous places are always at least a little disappointing when you finally get there,” my brother once said, “but not the Grand Canyon. You just gawk at it, bigger than you had ever imagined.”

But some of us love the human size of Canyon de Chelly even more than the Grand Canyon. Many days you can pick a corner and have it all to yourself.

We went back many times, after we moved to Arizona, and Canyon de Chelly became a kind of talisman for us. One summer, probably 1998, we decided to hire a Native guide and ride horses into the canyon’s further reaches. We found Dave Wilson, who arranged for us to go up Canyon del Muerto on horses. His teen sons Delbert and Delmar came along, too.

Canyon de Chelly National Monument is divided into two main forks, the southerly one is Canyon de Chelly itself, the more northern is Canyon del Muerto. The national monument’s name is a redundancy, like “Table Mesa” or “Glendale,” since its name derives from the Navajo word for “canyon” — Tsegi — turned by quasi-French transliteration into Chelly, pronounced “Shay.” (There is also a Tsegi Canyon on the Navajo Reservation, near Kayenta, further complicating matters).

Mummy Cave

Canyon de Muerto, or “Canyon of the Dead” got its name in 1882, when topographical engineer James Stevenson discovered two prehistoric mummified bodies in a rock shelter ruin, now known as Mummy Cave, and then named the north branch of the place Canyon de los Muertos, now shortened to Canyon del Muerto.

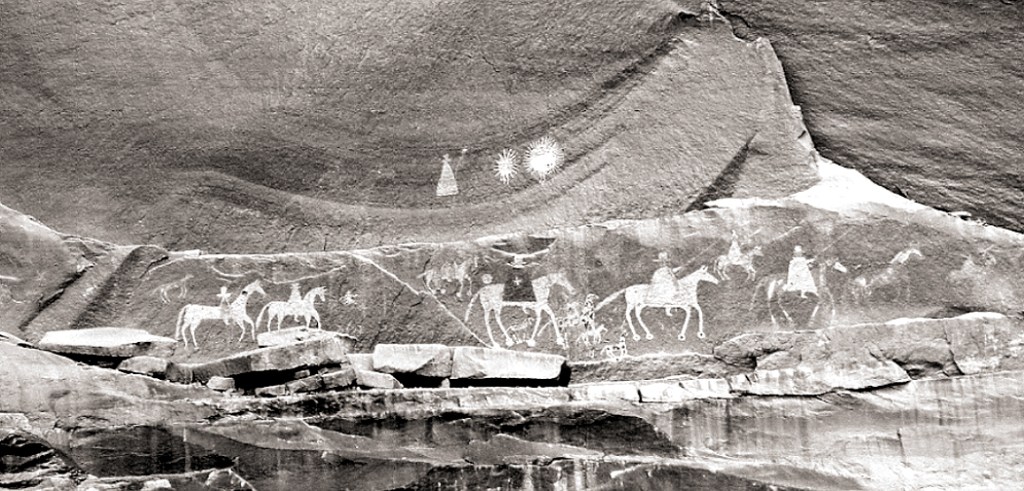

It could have been named for other reasons. Humans have lived in Canyon de Chelly for about 5,000 years. Long before the Navajo arrived, the prehistoric Anasazi peoples lived in the area and in Canyon de Chelly had built cliff dwellings to protect them from various warring groups. Those ruins are still to be seen in the canyons. And even after the Athabascan-speaking peoples, now called Navajo, arrived, sometime around 1700, the canyon continued to provide shelter from raids and wars with other tribes. It’s a long history of wars, battles and skirmishes, but two occasions stand out more recently.

First, in 1805, Spanish forces, under Antonio Narbona trapped about 150 Navajo in a cave high on the walls of the canyon. In his report Narbona stated “They entrenched themselves in an almost inaccessible spot, and fortified beforehand, we succeeded after having battled all day long with the greatest ardor and effort, in taking it the morning after and that our arms had the result of 90 dead warriors, 25 women and children and as prisoners three warriors, eight women and 22 boys and girls.” That cave is now called Massacre Cave.

Massacre Cave

Then, in 1863, the American Army began an attempt to bring the Navajo to a new reservation at Bosque Redondo in New Mexico, and Col. Christopher (“Kit”) Carson was tasked with rounding the Indians up to march them 300 miles to their new home. He had been given orders to destroy their crops and livestock, and the famous peach orchards of Canyon de Chelly. By March of 1864, some 2,400 Navajo had been collected and marched to New Mexico in the “Long Walk.” Thousands followed in later roundups.

And so, there has been plenty of muerto in Canyon del Muertos.

It might be a good place here to discuss Navajo superstitions and taboos. The canyon is filled with Anasazi ruins — good sturdy brick homes that just need a bit of sprucing up and new roofs. But taboos keep the Navajo from using them, or even entering them. Death is a principle taboo. A person’s name who has died should not be uttered. If someone dies in a hogan, traditionally, you move out and no one ever lives in it again.

There are many more — a list of them could make a book. One online posting names more than 200 such superstitions. Do not look at lightning in a mirror or it will strike your hogan. Do not watch clouds moving in the sky or you will become a slow runner. If you see a shooting star, you have to blow at it or you will receive bad luck. Do not put salt on a piñon nut or it will snow. Do not kill grasshoppers or it will give you a nosebleed.

We already encountered one, when the Navajo man with the pickup indicated the road to take by pointing with his chin and pooched lips. Pointing with a finger is considered aggressive.

In 1993, I went to visit famous Navajo painter Jimmy Toddy in his home in Wide Ruins, on the Reservation. Unlike the hogans he had grown up in, or the ranch houses that pass for government housing on the Reservation, in 1947, he built a two-story frame house with a stone foundation. I parked in the dust of his front yard and entered through a front door that was off its hinges. “I never fixed it,” he told me. “There are bees that made a hive there and it would bring bad luck if I didn’t let them fly anywhere inside or outside.”

At the newspaper where I worked, I became friends with Betty Reid, a Navajo reporter. She asked me to help her copy edit a proposal for a book she was planning.

“Yuhzhee is my Navajo name,” she said. “It means ‘short,’ or ‘small’ in English.” She spoke only Navajo until she was seven and her family, who raised sheep, lived near the edge of the Grand Canyon at a place called Bii Daa. “I’m a middle-age journalist who walked away from a traditional life to write for newspapers,” she said. “The two worlds are very different.”

I once asked her about the superstitions. “Yes, we are very superstitious.” “Do you believe in them still?” I asked. “Oh, no. Very few younger Navajos still hold on to such things. They make no sense.”

She paused a beat. “I still do them, though.”

But back to 1998. My wife, Carole, had been fascinated by Indians and Indian culture since she was a little girl and collected arrowheads turned up by North Carolina farmers plowing their fields. She had always wanted to ride horses with Indians, and now she was getting her chance with Dave Wilson.

We drove to his home, on a bluff just above the entrance to the canyons. His wife invited us in as Dave got the horses ready. It seemed like a very ordinary ranch house with modest furnishings, except that it had a dirt floor and just by the front door was a TV console with its tube removed, letting it serve as a home for a few chickens.

I had never ridden a horse before, if you don’t count a pony ride at the state fair when I was a little boy. Dave assured us his horses were used to beginners and it would be easy. Just follow him.

We mounted the horses and followed Dave and his two sons, each on his own horse. He didn’t lead us down a road, but straight down the side of the hill, at a precipitous angle. I had to lean back so far in the saddle, my head rested on my horse’s rump. Luckily, the horse knew what he was doing. I certainly didn’t. Their hooves slid and kicked up gravel the whole way down.

At the bottom of the hill, it flattened out and we rode into the canyon mouth, turning left into Canyon del Muerto. My horse was balking. It lagged behind the rest and they had to stop so I could catch up. At one point the horse, apparently impatient, began to trot after the others and I feared I would fall off. New Jersey boys make poor cowboys.

What can I say? Not only was I a poor equestrian, but my body was not built for the saddle. One sees bow-legged cowpokes in the movies, who have long acclimatized to the barrel-shaped body of a horse, but my straight legs were agonizingly twisted to the stirrups, feeling like my knee cartilage was being torn sideways from my leg bones. It was a form of Medieval torture. Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.

Carole, on the other hand, was in horse heaven. I tried to last through the first few miles, but eventually, I had to get off and let my legs assume their normal lines. I limped around my sturdy mount, trying to regain the use of my knee joints.

Dave had, no doubt, come across such greenhorns before and kindly offered to continue our tour of the canyon by car, and sent one of his sons back out of the canyon to bring back his station wagon. About 20 minutes later, it arrived and we all got in and began the tour again. The older son led the horses back home.

But then, the car got a flat tire. Neither Dave, nor his remaining son, Delbert, cussed or fumed, but acted as if this were just a normal course of events. We got out and waited. Dave took out the spare, but it was flat, too. He never expressed any emotion about it all. It’s just normal.

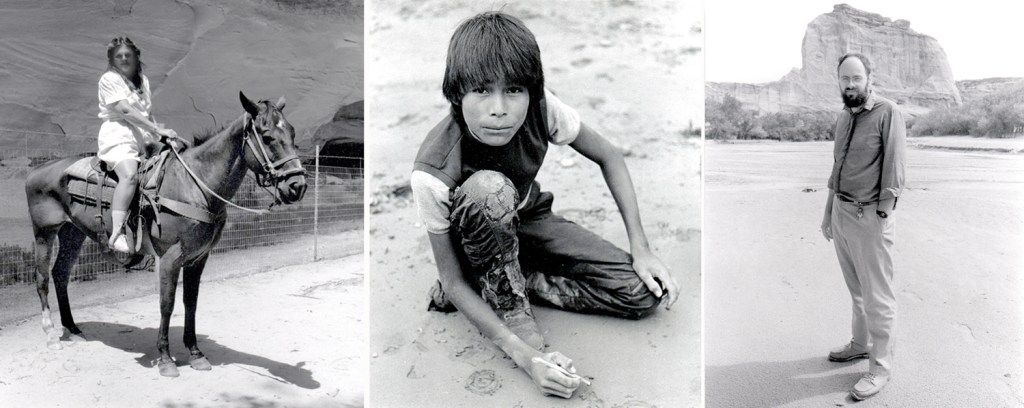

Carole on horseback; Delbert Wilson drawing; me, standing

Other tour cars passed us, other horse tours. But Dave never said a word to any of them, never asked for help. We sat in the sand for perhaps two hours. Delbert began drawing in the wet sand with a stick, to the delight of Carole, who was an art teacher. The sun went behind the canyon walls and it began to darken.

It must have been about 7 p.m. when another car arrived, driven by Dave’s wife. We all got in and drove back out the canyon and up to Dave’s house (taking the road this time), where they apologized for the cock-up. They offered to feed us supper, but Carole wanted to get back to our motel. Dave’s wife gave Carole a gift of a small necklace and we all smiled and thanked one another.

The impassivity that Dave showed with the problems we faced, we came to know as one of the cultural characteristics of the Navajo — which we learned over time with the many other Navajos we came to know and become friends with. I don’t know what Dave was feeling inside, but outwardly, it was all the same to him.

When we got back to Phoenix, we mailed a box of presents up to the Wilsons.

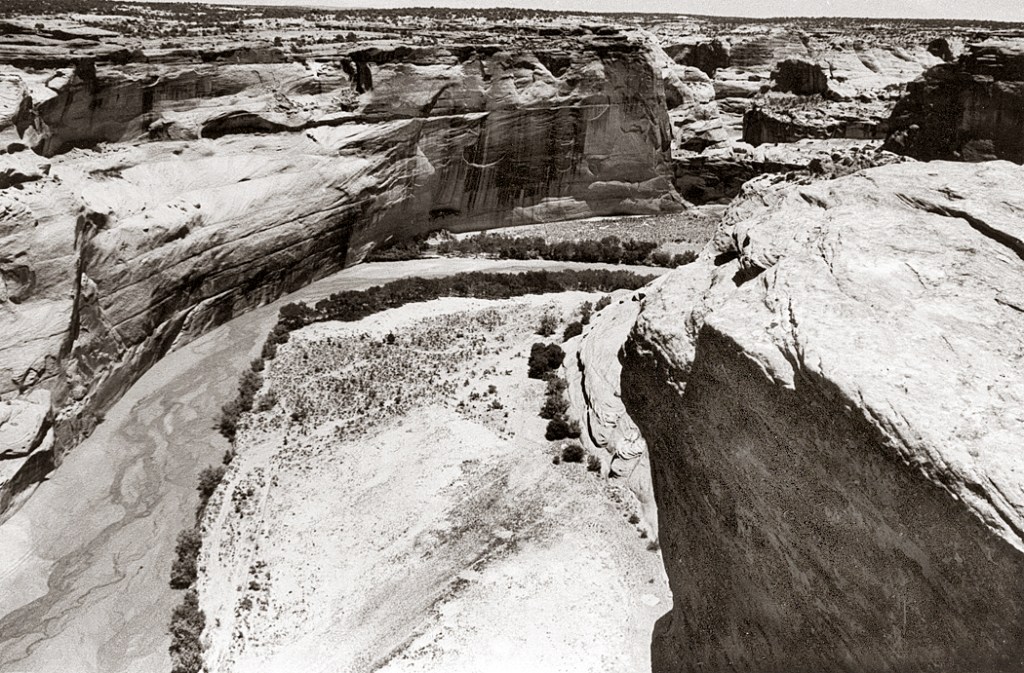

Canyon de Chelly National Monument is situated on land owned by the Navajo nation, and travel in the park is open only to tribal members or those accompanied by authorized Navajo guides, such as Dave Wilson. The only exception to that is a public trail from the cliff edge down to the White House Ruins, about five miles up from the canyon mouth. You walk down a steep path, 600 feet down through switchbacks and tunnels to the canyon floor. The trail is about 2.5 miles long and leaves you at the foot of White House Ruins, an Anasazi cliff dwelling, first built around A.D. 1060.

The pueblo originally had an estimated 80 rooms, on two levels, with some featuring a light plaster, which led to the Navajo name for the site, Kinii’ ni gai — which means “White House.”

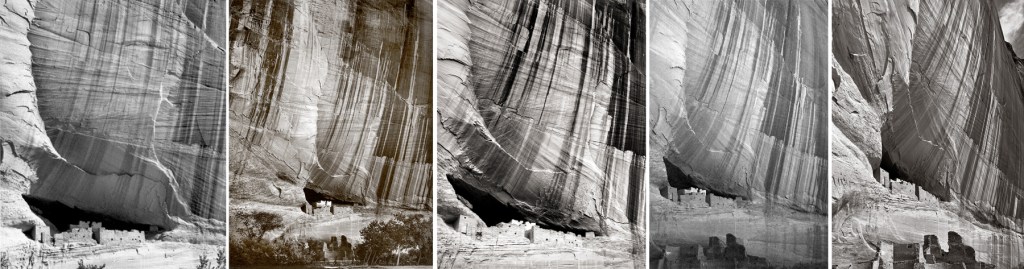

White House ruins by O’Sullivan, Gilpin, Adams, and me

The cliffs above the ruins are streaked with desert varnish, a mix of iron and manganese oxide, that makes a visual scene that is absolute catnip to photographers. The first photo of the ruins and the varnish was made in 1873 by Timothy O’Sullivan, but a parade of others have followed, including Laura Gilpin in 1930, Ansel Adams in 1950 (having made an almost identical photo in 1942), and me in 1981. Gilpin visited and studied the Navajos and the land they occupy and published, in 1968, the classic book, The Enduring Navajo. It is still in print.

The scene absolutely frames itself, which means that hosts of images are basically repeats.

Photos by Tad Nichols, 1931; Jerry Jacka, 1976; Don Whitebread, 2009; Patrick McBride, 2012; Richard Boutwell, 2017

It’s a highly tempting subject and I’m sure that many other tourists have made the same picture, now with their iPhones.

Without getting down into the canyon, you can drive along its rim, both along the south branch and the north, with overlooks at such famous vistas as Spider Rock and Massacre Cave.

You stand at the rim of Canyon de Chelly on the Navajo Reservation and look down to the braided stream at the bottom that scoured this great hole out of the sandstone and wonder how long it must have taken. Then you see the tiny Anasazi relics built into the walls of the rock and realize how long people have been living here, and then you see the sandstone itself an think about how much longer ago — exponentially longer — that ancient river deltas deposited the silt that later became that stone.

We visited Canyon de Chelly many times, and at one point, Carole applied for a teaching job on the Reservation. We drove up for an interview, but the terms of the employment contract would have made it difficult to ever afford to live there — the 10-month contract came with a 10-month lease on a home, meaning we would have to leave with all our belongings during the summer months. It was clear they would rather have a Navajo teacher than a bilagáana. We couldn’t begrudge them that.

Click on any image to enlarge