I remember the Before Times. It’s different now.

On September 27 the remnants of Hurricane Helene turned Asheville, N.C., into a post-apocalyptic landscape. Fallen trees blocked streets and roads were turned into creek beds. Power lines were downed everywhere and the two rivers of the region carried whole houses downstream. Bridges are gone. City water lines destroyed. The buildings that remain in the lower areas of Buncombe County are larded with a foot-deep layer of toxic mud. People died.

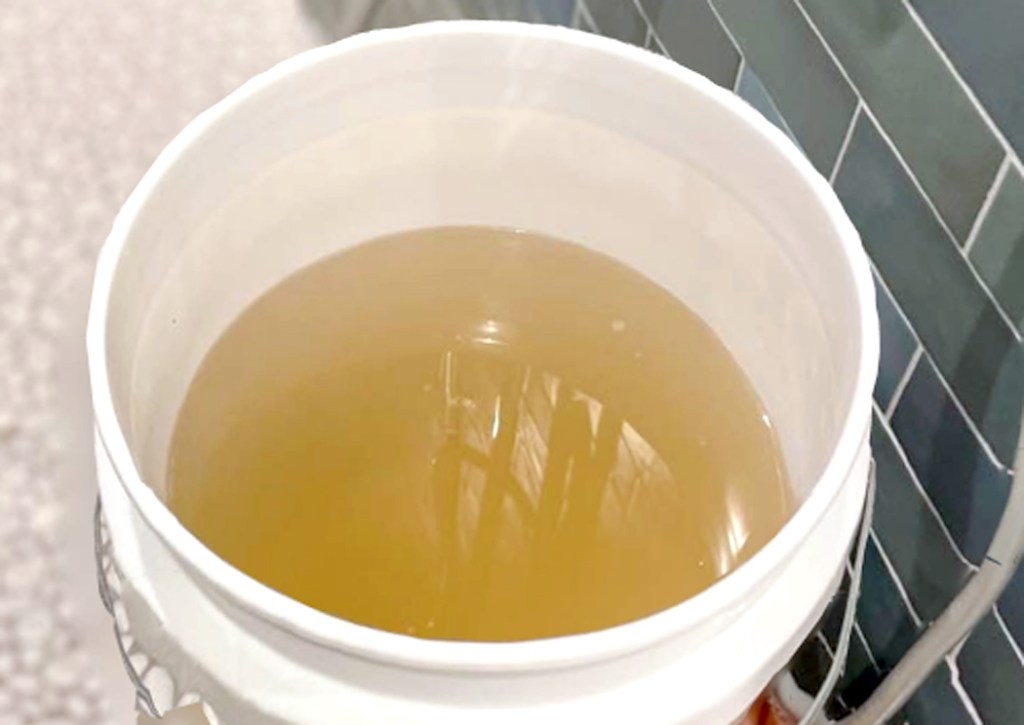

It has been a month since the storm and there are still many roads closed, homes without power, and the city water is unfit to drink. We have to boil it even to wash dishes. And what comes out of the tap is a cloudy, rust-colored fluid.

It has been so bad, left so many people stranded or homeless, that Jose Andres’ World Central Kitchen has come to feed those in need.

At our house, we were otherwise lucky. Our neighborhood had fewer fallen trees than others and we were high enough in elevation that we avoided the flooding. Outside our little neighborhood, though, it looked very, very much like the devastation of Katrina.

Damage in Swannanoa

The first week after the storm was hellacious. No power; no water; no phone; no wifi; no cable; no AC. Dark at 7 and no lights anywhere. The fridge and freezer silent. On the fourth day, we had to throw out all the food in both and scrub the interiors with bleach to kill the faint smell of mold.

With no water, we could not flush the toilets and, being unable to stop the physiology of the human body, we had to go somewhere. The commodes were becoming rank.

This was a problem that everyone shared, and so, by the second full day, neighbors had pulled together and set up a tent on the street corner where we could go, share stories, rumors and advice, and by the third day, they had food and bottled water to hand out to those who needed it. One neighbor had a swimming pool, and if you had a bucket, you could dip it in the pool for water to flush toilets.

Across the street from us, Dorothy, a retiree like us, and her grown son, Anthony, brought us a bucket so we could go down the street and dip it in the pool. Because we are old and five gallons of water is heavy, Anthony carried the water himself. That afforded us one flush a day. By the fourth day, Anthony had found a children’s wagon and was delivering flush water around the neighborhood. It was still once-a-day, though.

Neighbors helped neighbors. Some went house to house to check on them. Two fresh-faced young women knocked on our door. They had weak cell-phone coverage and had received a text message from my granddaughter in New York, a former schoolmate, asking them to check on grandpa. They sent a text back to her telling her that we were OK.

The street-corner tent set up a message-board where people could ask for supplies they needed, or to offer what they had. Our next-door neighbor, who had just moved in, had no food and we collected a few non-perishables and brought them over. Others came to us and gave us boxes of cereal or, in one case, an entire box of cellophane-wrapped brownies.

But it seemed as if we survived that first week eating little but apples and Fritos. I had a case of bottled water and some soft drinks.

“This is how are ancestors must have lived,” Anne said. “Except, they had water.” Dark all night, light for reading in the daytime. We read an average of a book a day during that first week, with little else to do but sit and wait. At night, we had candles burning on the piano — but not like Liberace: They were squat votive candles. And we would continue to read in the dark with flashlights.

There was a constant whirr and buzz, even through the night, of workmen chainsawing fallen trees and power crews trying to reattach downed lines. We saw trucks from out of state driving in caravans through the neighborhood, cleaning up and repairing 24 hours a day. Overhead there were helicopters and airplanes; hardly 10 minutes would go by before another one — or two at a time — skitted across the sky. It reminded me of film from Vietnam, except there were also drones.

And it was a huge military operation. National Guard and Marines, search-and-rescue operations looking for people cut off from roads or stranded on roofs, or dog teams looking for bodies in the debris. I have since heard ignorant people spout conspiracy theories about the failures of FEMA or the government in general, but those trolls weren’t there. I have never been so impressed at the seriousness and effectiveness of everyone, government or civilian working to recover. The lies being spouted are reprehensible. Actually, evil.

The Asheville airport was covered with military planes and scores of copters. The only way into the area for the first days was by air. I-40, the main highway, was cut off on both ends by landslides. The bridges along I-26 were washed out. All roads in and out of Buncombe County were blocked and closed. If we had wanted to leave, we couldn’t.

By Day 6, the mudslides blocking I-40 East had been provisionally cleared and road traffic could be resumed, and trucks with relief provisions could climb up the Blue Ridge into Asheville. Power had come back to our neighborhood (although many others remained dark). There was still no running water and all of our food had been ruined, except for those canned goods. We hadn’t had a shower in a week.

The problem for us was that the car had almost no gas left and no gas stations were open. But on Day 6, we got word from Anthony that a station in Fairmont — about six miles away — had reopened. We drove and miraculously, there was no line. We tanked up. We could leave.

Our first thought was to take a few days’ clothes and head to a motel in the flatlands, where the storm damage was less, and spend a couple of days getting cleaned and eating some hot food. We drove to Hickory, about a hour away, but found the motels were full. Outside of Hickory, we found one that had a single opening — the Presidential Suite for $180 a night — and we took it. The motels were not full of tourists; they were full of construction crews and aid workers: wiry, grizzled men with hard hats and leather-tanned faces who were commuting to Asheville to restore power or dig out debris. Their trucks filled the parking lot.

But we did get a hot shower and across the street there was a Mexican restaurant where we got a hot meal.

For the next two and a half weeks, we stayed with my brother- and sister-in-law in Reidsville, N.C., where they fed us and caught us up on all the events of the outside world we had missed. It would have felt like a vacation except for the hollow knot of anxiety in my gut. We drove home on Monday to find the house had not burned down, been burglarized or taken over by raccoons.

But there was still the problem of water. We are under a boil-water notice, which mandates — not suggests — that we boil the tap water for 1 minute before using it. It is still so cloudy that even after disinfecting it is not drinkable.

Blue Ridge Parkway damage

The storm was prodigious. Official reports note that 2,300 structures were destroyed completely or made uninhabitable. That’s homes, stores, and other businesses. The Blue Ridge Parkway was closed for its entire length in North Carolina and its director said that some 10,000 trees had fallen into the roadway. Parts of the Parkway were covered in landslide mud and other parts had their pavement washed away entirely. In several places the North Fork Swannanoa River has carved new courses, leaving at least one bridge over dry land and the water a hundred yards to the west.

Official death count for Western North Carolina totaled 96 (subject to revision as new data arrives), with 42 of them in Buncombe County alone. The NC total was nearly half of all deaths from Helene in the U.S.

There are reasons Western North Carolina was so hard hit. While the storm made landfall in Florida, and traveled north across Georgia and South Carolina before tailing out in Tennessee, those states suffered from hurricane and tropical storm damage alone — bad enough. But in Western North Carolina, the meteorological and geological circumstances doubled down on the effects.

I-40 Before and after

First, the area had already had days of rain soaking the ground before Helene. Second, the storm brought an enormous amount of water vapor — twice as much as the previous record from the 2004 double whammy of hurricanes Frances and Ivan. Third, the counterclockwise spin of the storm meant that its high winds struck the Blue Ridge escarpment head on, forcing the water-soaked air upwards, with both the Venturi effect speeding up the winds, and the adiabatic cooling that squeezed all that water out of the clouds, with Mt. Mitchell recording 24 inches and the Asheville airport getting 20 inches. One Forest Service weather station measured 31.33 inches of rain from September 25 to 27, piling Ossa on Pelion.

That’s bad enough. In flatter terrain, that would account for two feet of water over a wide landscape. But in the mountains, all that water gets funneled down into the valleys, where it collects in raging torrents, wiping away whole towns. Consider, say, five square miles of land, hit with two feet of water and condensing that water into a hundred-yard wide channel.

River Arts District, Asheville

That’s what happened along the Swannanoa River in the community of Swannanoa, along U.S. 70, where mountains both north and south dumped their drainage. Or along the French Broad River south of downtown Asheville, where the old industrial district, turned River Arts District, was wiped out. Or the narrow 14-mile Hickory Nut Gorge, which drops about 1,800 feet between the town of Gerton and Lake Lure, where much of the road is now reduced to a rocky creek bed.

There used to be a road here, Hickory Nut Creek

Estimates for the damage are currently set at $53 billion, although that is subject to revision. That is a North Carolina record.

I have concentrated on Asheville and Buncombe County because that is where I live. And I can see the destruction first-hand as I drive around. But it is much of Western North Carolina that shares the calamity.

French Broad River, Asheville

There is no guess as to when this part of the country will return to normal — although that will be a new normal, not the old one. Probably a year, at least. But people are all working hard to get there, individuals, civic officials, volunteer help and federal government. Some things have come back sooner than expected.

But so far, we are eating on paper plates and drinking from disposable cups and eating frozen Stouffer dinners and hoping with crossed fingers that our tap water will at sometime run clear again.