When faced with some difficult problem of geometry or algebra, I usually just throw up my hands and say, “Don’t look at me, I was an English major.” I’ve noticed, however, that Anne will always phrase that a little differently. She say would shrug and say, “I’m an English major.”

The difference in tense speaks to how we each view ourselves and our place in the world. When it comes to things such as grammar or usage, I tend to be more flexible while Anne has more in common with a British sergeant-major. For her, there is right and there is wrong.

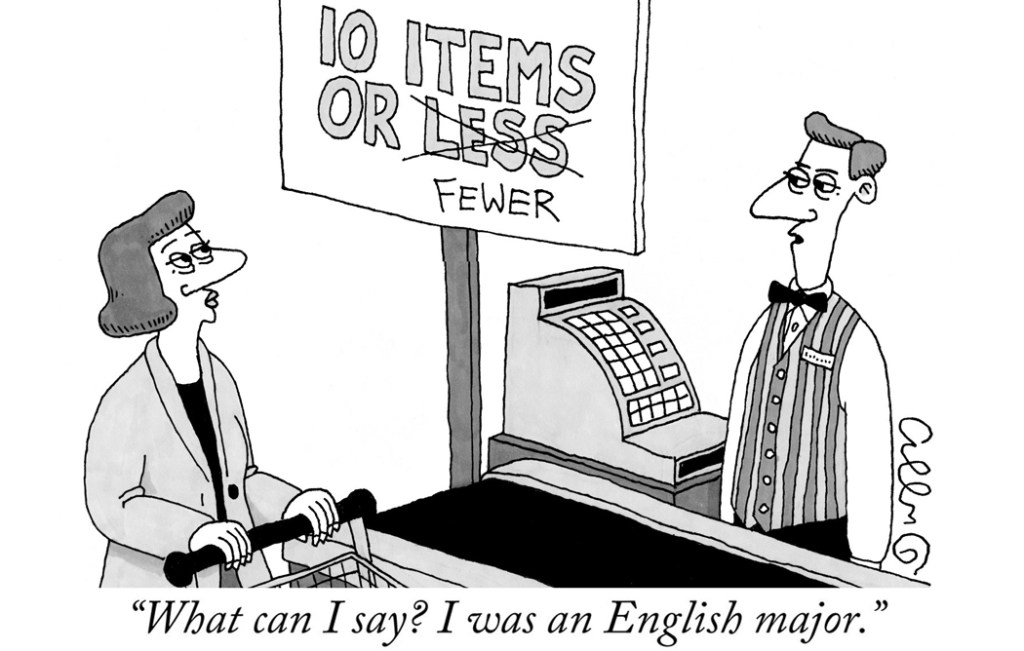

Of course, there are those more lax than I am and some more unbending than Anne. It is a spectrum. I have many peeves about poor usage, and especially misused words. I admit the definitions of such words as “enormity” and “disinterested” are changing and in the future they will mean whatever their speakers intend them to mean. But for now, it gives me hives when I hear a newscaster say, “There are less people having babies now.” Drives me nuts. But for Anne, this is not so much fighting a rear-guard action against change, as building a fortress against incoherence. “Things mean what they mean; illiteracy is no excuse.”

To gauge where you fall in the spectrum, consider a simple sentence: “Who did you give the book to?” There are two things “wrong” with this sentence, but how you intend to fix it, or fix it at all, may help you decide.

If you are one of those people who still believe that a sentence should not end with a preposition, then you will change it to, “To who did you give the book?” But that sounds all wrong. No one would actually say that.

And that’s because of the other problem — “who” should be “whom.” And so it becomes “To whom did you give the book?” But that can sound pedantic. So, you choose one mistake over the other and wind up with, “Whom did you give the book to?”

So, you pick your poison. Of course, in reality, you wouldn’t say any of these. What you would actually say is “Hooja give the book to?” And language is filled with hoojas.

We don’t speak word-by-word, but in phrases, and those phrases become units all their own. “Jeet jet?” Did you eat yet? “I’m gonna sell the old Ford.” “I dunno what is correct.” Sometimes these vocal elisions make it back into print. How many times have you seen “I would of gone” instead of “I would have gone?” But, of course, this isn’t so much an illiteracy but a back-transference from spoken language. You say, “I would’ve gone.” If that’s what you hear, you might very well think you’ve heard “would of” and then use it in your Tweet.

These back-transferences now often make it into print, mostly in dialog in fiction, to make the speech sound more natural. Ultimately, these have a chance to become standard English, and in the same way that “a nuncle” became “an uncle” by printing what the ear heard. At some point in the future, it will be in the Chicago Manual of Style to write, “We’re gonna study alot of stuff we dunno much about.”

That brings up “a lot,” which is one of the main bugbears for Anne. She yells at the page when she comes across “alot.” The word bothers me, too, but not as much as it rankles her. And I have to admit that at some point in the not-too-distant future, it will be common in dictionaries.

That’s how languages go. What is an ugly and ignorant solecism in one age becomes propriety in the next. Garish new money becomes respectable old money when the billionaire entrepreneur is knighted.

So, language changes, but almost never by fiat. Suggestions can be made. They may catch on, they may not.

One of the most successful came with Noah Webster’s desire to create a “more American” spelling. His 1806 Compendious Dictionary of the English Language sought to simplify spelling. Eventually, his changes caught on and we now spell “color” without a superfluous “u,” and “theater” with the “e” in its functional place.

Among British language reformers were George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, Alfred Tennyson, and Charles Dickens. A Simplified Spelling Society was created in 1908 (currently, the English Spelling Society). America had its own Simplified Spelling Board, begun two years earlier, with a grant from Andrew Carnegie. President Theodore Roosevelt issued an order for all federal documents to adopt the suggested new spellings. That lasted short while. The old spellings were soon re-instated. The Louisville Courier-Journal published an article ridiculing him, which stated: “Nuthing escapes Mr. Rucevelt. No subject is tu hi fr him to takl, nor tu lo for him to notis.”

But if these things can’t be imposed from above, they can take hold from below. Consider the effect of Twitter and the Internet on language: “R U There?” Texting language now occasionally shows up in print. Expect more of it.

Language changes because there is a need, or because the newer versions seem simpler, or get adopted because technology or culture changes.

There are those who want to invent new pronouns to accommodate the rising awareness of gender fluidity. Some new words have been floated, such as “xe,” “xyr,” “em,” or “fae.” None has caught on. Given time, one of these may win out and may become normal. I don’t count on it. But the use of a so-called “singular they,” has long infiltrated common usage: “Everyone should take their hat off.” Solves an awkward problem (“his or her” is just cumbersome) and has actually been hiding in the language for centuries, no matter what edicts are handed down from hide-bound grammarians.

The last time a new gender-bound word has successfully entered the language was “Ms.” It is now used by almost everyone, and by many who don’t even know it was lobbied for in the 1970s when Ms. magazine first began publication. (And first proposed as far back as 1901). It is just a normal part of our vocabulary now, although those of us who remember when it was new can recall the angry backlash that came from the stodgier sections of our society.

Another group wants to get rid of apostrophes in contractions. Dont need them, they say. Context makes the meaning clear. “What Id like to study is the human id.” “Dont eat the yellow snow.” There are very few places where the meaning isnt clear, and even with the apostrophes, there is plenty of confusion in the language.

Linguist Geoff Lindsey points out that in spoken language, we don’t really ever hear the “t” in such words as “can’t.” That when we speak them, the difference between “can” and “can’t” isn’t in the “t” but in the vowel. If you say, “I can’t do it,” you actually say, “I can’ do it.” But you pronounce the “a” as the “a” in “bad,” while when you say “I can do it,” the vowel goes like “ken” — “I ken do it.”

So perhaps we don’t need the “t” — or perhaps we can just take out the apostrophe and say “cant.” And then write “ken” when we mean the opposite.

I’m not sure eliminating such apostrophes would make up for the number of supererogatory apostrophes added to create plurals. This is an ugliness that leaves me feeling like King Canute before the sea. It makes me hiccup every time I see it, but I am powerless to stop the rising tide. Perhaps in 40 or 50 years, even the Chicago Manual of Style will accept it as standard.

There are many normal progressions in the history of languages, expected simplifications and sometimes added complexities. Words that used to be two words became hyphenated expressions and then turned into compound words. Cellphone used to be cell phone; webpage was once web page, then, briefly web-page; hotdog was hot dog. English moves in the direction of eliding these words back down to one.

It has been pointed out that the perfect tense in English is fading. Where we once said “Have you finished yet” we often say instead, “Did you finish yet.”

Irregular verbs are being replaced by regularized versions. I remember when I was a journalist and required to use Associated Press style, we had to used “burned” instead of “burnt,” or “dived” instead of “dove.” I liked the older words with more taste in the mouth. But the direction of our language is toward regularization, at least in words less seldom used. We now sneaked instead of snuck; pleaded instead of pled; dreamed instead of dreamt. Maybe at some point “I did it,” will become “I dood it.”

Also, as we head into the soft middle years of the new century, borrowings from Spanish will become more common. They’ve always been there, from rodeo to hoosegow, but newer ones will proliferate. English has always been promiscuous and up to 80 percent of our vocabulary has been acquired from other languages (depending on your starting point — where was English first English and not related at all to what we speak now?).

And speech is the important issue. English has had a relatively quiescent period for the past several hundred years, as the language has been held steady by print. But as electronic media take over, spoken language is becoming more central, whether spoken on television or radio, or mimicked in texting and tweeting. Before print, English spelling varied widely. It looks like that Wild West of orthography could be our future.

And if so, then the hoojas will take over the tongue. And the didjas, the woodjas, the havyas and canyas.