Now that I am past-ripe and a wizened old man, what do I spend my time thinking about? Certainly not the things I thought, or cared about when I was in my 20s or even my 40s. Gone is any career ambition, or the delights of sex or ownership or the esteem of my peers.

I am not the same person I was when I was young. I can’t feel bad about who I was, or feel guilt about the stupid things I thought or did. That was then and cannot be changed. And one of the most important lessons I have grown into is the realization that I can effect very little change or improvement on the world. It will always be joyful and cruel, intelligent and mind-numbingly dumb, individual and collegial, important and inconsequential. I can attempt to reduce my contribution to the cruel, dumb and evil.

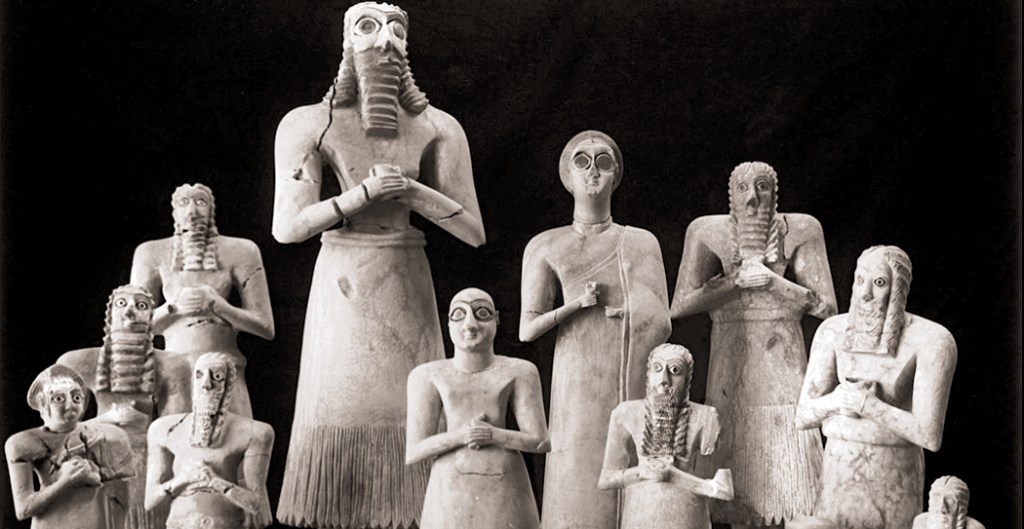

I think also the related thought that while I am an infinitesimal mote in the cosmic history, and count for absolutely nothing in the big picture, that so much of the world can fill me with afflatus and pleasure. And how much meaning such things afford me.

Beyond that, I think about the experience of being alive, in the sense of paying attention to the physical world around me. I don’t mean “mindfulness,” which is a repellent and trendy buzzword. To say, “being in the moment” is not quite it. The moment doesn’t much count, but what does is the fact of paying attention, and feeling a part of it all. Me and the universe, a single thing. My emotional connection is a silken thread in the weft of an immense fabric.

And so, I concern myself instead with whether I am a good person, whether I have atoned for the foolish, selfish or hurtful things I may have done or been in the past. Do I listen? Am I generous, especially in spontaneous fashion? Do I try to make others happy?

Then, I think of death. Not in any romanticized Sorrows of Young Werther way, but rather the recognition that extinction is within touching distance. Blankness, non-existence, evaporation. I never think that I have existence beyond the body that generates my consciousness. When I die, my spirit will not hover in some afterlife; rather, I will cease being created, moment by moment. Gone. This is not something I spend much time fearing, but rather a speculation I attempt in cool realization of fact.

Death is now always sitting on the front steps waiting for me to answer the door. And not only my own death. Not even principally my own.

I cannot avoid experiencing grief. I don’t mean sadness, but gut-hollowing grief and the universal experience of loss. There are two such experiences that humanity gets to share and the irony is that although it is common to all, to each it feels as if we are the only and first ever to feel it. Those two things are love and later, grief. It can be sympathized with, when someone you care about goes through it, but it cannot be shared. It is the most personal intimate thing I have ever been through. You may think that granite is real, but you don’t know real until you know grief.

These are all some of the things that occupy my brain throughout the day.

They are not all cosmic. Just as much a taker-up of my brain power, is language. How can it work? Why can I understand a thick Brooklyn accent and an Appalachian twang although the sounds they generate have little to do with each other? Why we think language corresponds to experience when it clearly refers primarily to itself. It is a parallel universe. Yet, we believe it describes reality. Why?

What does not much concern me is politics. I have my own beliefs, of course. And I vote. But as I wrote some 40 years ago, “Politics answers no question worth asking.” It may make life possible, but does not explain why we should live.

To be truly alive is to pay attention. Engagement. Being aware.

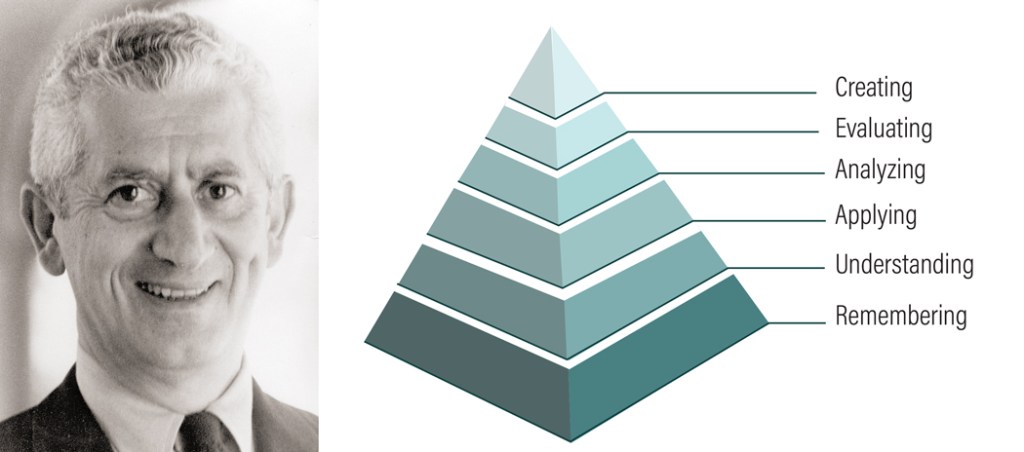

When I was a callow college student brilliant at giving a professor what he or she wanted, taking it all in, and giving it all back. But then, one of them shocked me awake by giving me a D grade for doing just that. He didn’t want me to give him what he wanted. Regurgitation isn’t learning. He wanted me to engage with the material, directly. Not words about the material. And he made me do actual work, no more coasting on cleverness. He prevented me from settling for glib. It was one of the most important lessons I ever got. “Engage with the subject.” I have been forever grateful for that. It has been my guiding principle.

A famous British comedian has reckoned, in a serious moment, that the most important human emotion is gratitude. He called it the “mother of all virtues.”

Others, like love or hate, may be more immediate in power, but love, for instance, is of little use without the recognition of it gained through gratitude. And as I look back over a long life, I feel gratitude for so much.

The first is an impersonal gratitude for the mere fact of the spark of consciousness between two infinite darknesses. And the awareness of that gives me not the unreflective “thanks for that,” but a deep and pervasive gratitude for just breathing, and being aware that I am breathing.

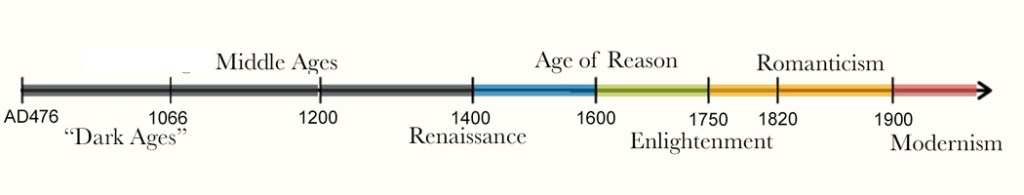

The fact that I was born in an unprecedented era — one of relative peace after two disastrous world wars, and an era of modern medicine, booming economy, wide education, increasing social justice (though far from perfect) — has not gone unnoticed. All are to be grateful for.

Other gratitude is more focused on people. Primarily I am grateful for the 35 years my late wife, Carole, was willing to share with me. She, and those years, made me who I became more than anything else — and I include the parents who raised me and the DNA that governed much of the happenstance of existence. No, she was most responsible. I cannot thank her enough and always feel unworthy of the love she offered me. She died seven years ago. I grieve for her every day.

I do, however, recognize what my parents gave me and wish I could, now that they are gone, share my gratitude with them. I cannot say they were exceptional parents, but they gave me a sense of security, a sense of fair-mindedness, of tolerance. And there was never any doubt from them that I would be college educated and set off on a successful life. I am grateful for the fact they never forced a religious orthodoxy on me. And that they made sure we traveled and saw a wider sense of life.

I once made a list of all the people I feel gratitude toward. It went on for pages. I can’t include them all here, and you wouldn’t know who they were, anyway. But they were important to me. You surely have your own cast of characters and your own gratefulness. None of us grows purely on our own.

And so, aiming into year 77, I can admit such a welling of gratitude that the thought of the non-being shortly ahead of me seems more like a fine rounding-off than a horrible cheat.