One of the most popular — but meaningless — excrescences in current culture is the explosion of Top 10 and Top 5 lists. They are everywhere, on the internet, in magazines and newspapers, and on TV.

When I took an early buyout from my newspaper a decade ago, it was largely because, as a feature writer, I was increasingly asked to provide what are artlessly called “listicles,” that is, newspaper articles in the form of lists: “Five things to do in Sedona,” “Five best pancake toppings,” “Top five wines from Indiana.”

The direction the newspaper was going was to avoid any actual writing of prose and substitute a quick list — easy to put together, popular with readers, and completely and utterly devoid of substance. I could see the handwriting on the wall, and decided it must be time to leave the profession.

Of course, I am guilty of making such lists, too. We all are. For this blog I have written several lists, including the ultimate lists of the 50 greatest lists of all times (link here). My list of the Top 10 films of all time has at least 40 movies on it. Heck, my list of best foreign films counts 100 of them (link here). But I am now doing penance for my sins.

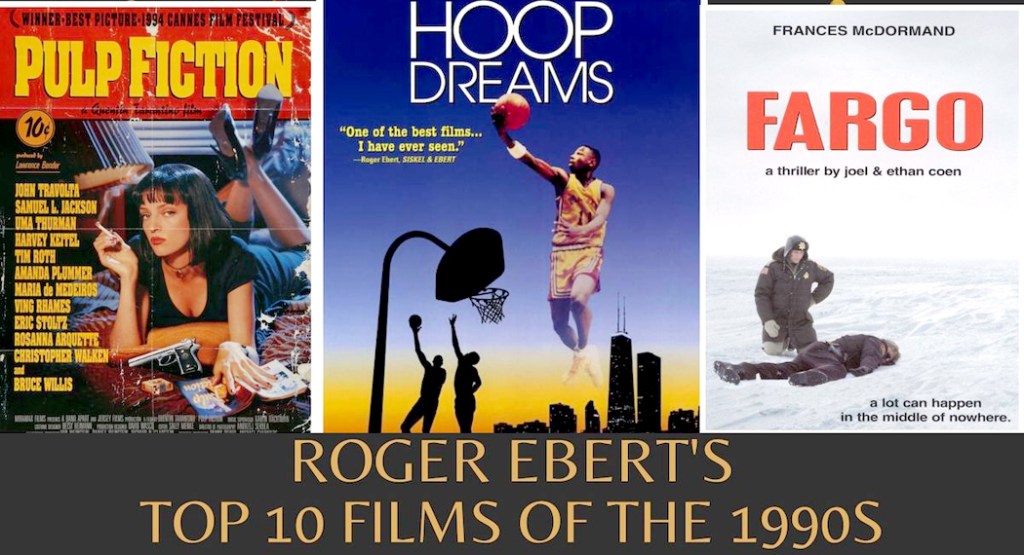

Top 10 lists, such as the year-end lists by movie critics, are only just a record of the taste and opportunity of the critic in question: No critic has actually seen all the movies released in a given year, and the final choices depend entirely on the likes and dislikes of the reviewer. There is usually some overlap, but no two critics will offer quite the same list. Such lists are fun to read, and may be a vague guide to what films might be worth seeing, but as an ultimate judgment of quality and ranking, the lists are just smoke to blow away with time.

There is no actual, objective, outside omniscient and divine judge to parse differences between, say The Godfather and The Godfather Part II. Above a certain level, it is all cream.

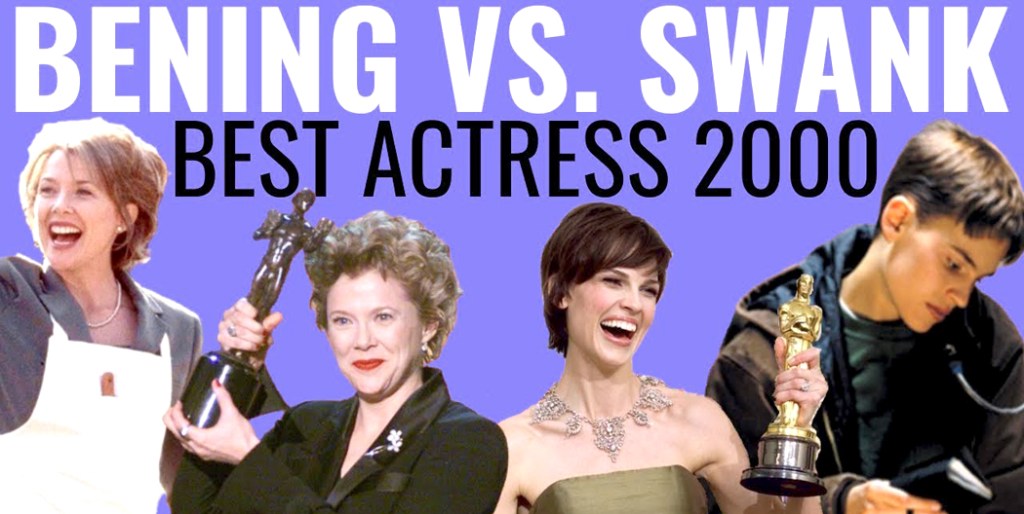

Many of the artists who show up on such lists, whether actors or directors or costume designers, know full well that art is not a competition, and that comparing a great tragedy and a great comedy is worse than apples and oranges. Hilary Swank was voted best actress in 2000 for her role in Boys Don’t Cry, and it was a powerful and moving performance, no doubt. But was she quantifiably better than Annette Bening, Janet McTeer, Julianne Moore and Meryl Streep? They were all good — as were a passel of actors who had films out that year who weren’t even nominated. Should Moore consider herself a failure because Swank came out on top? Silly, of course.

People working at that high a level of accomplishment are all beyond mere ranking.

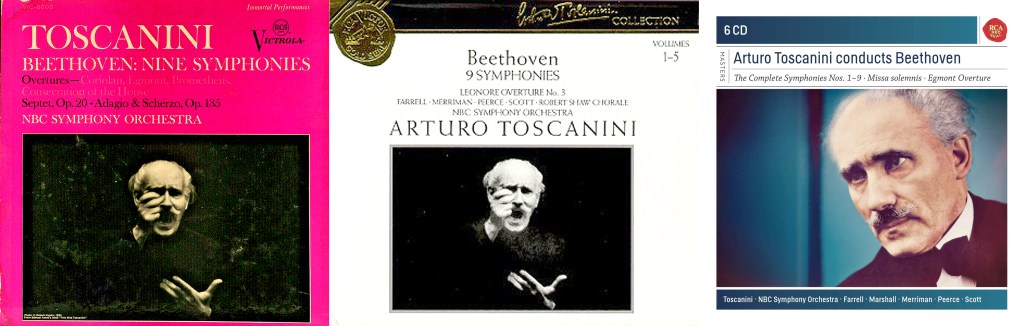

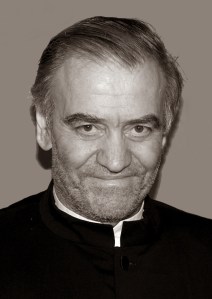

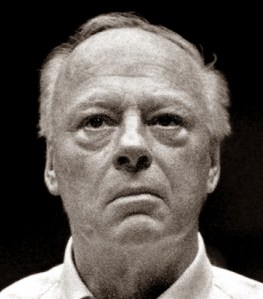

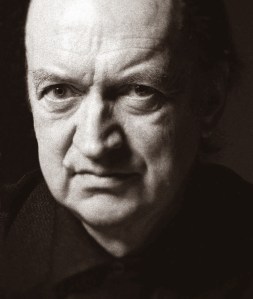

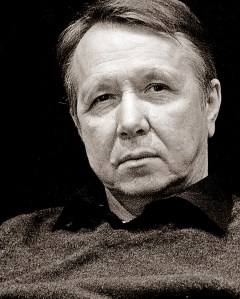

This came flooding back on me because lately, I’ve been immersing myself in recordings of Beethoven symphonies. When I first began listening to them, more than 50 years ago, I had the Toscanini set on LP, which I played on one of those ancient drop-front Sears Silvertone record players, and as a mere youth, thought Toscanini was the greatest conductor ever in the history of the universe anywhere. When you are young, you are prone to rash and categorical judgments. (I have always owned a set of Toscaninis, in its various release permutations and remasterings. I’m not ready to toss him overboard just because I have found others who also do well.)

Since then, I have heard the music uncounted times in concert and even more often on recordings. For many years, in the middle of my time on earth, I foreswore them, having — as I believed — worn out my ability to hear them as anything but background music. I knew them too well; they were too often programmed at concerts. Another Beethoven Fifth? God help us.

But after taking a 30-year break (outside of the concerts I attended or reviewed), I have come back to them and can hear them all again with fresh ears. And they are a marvel. There is always something fresh to hear.

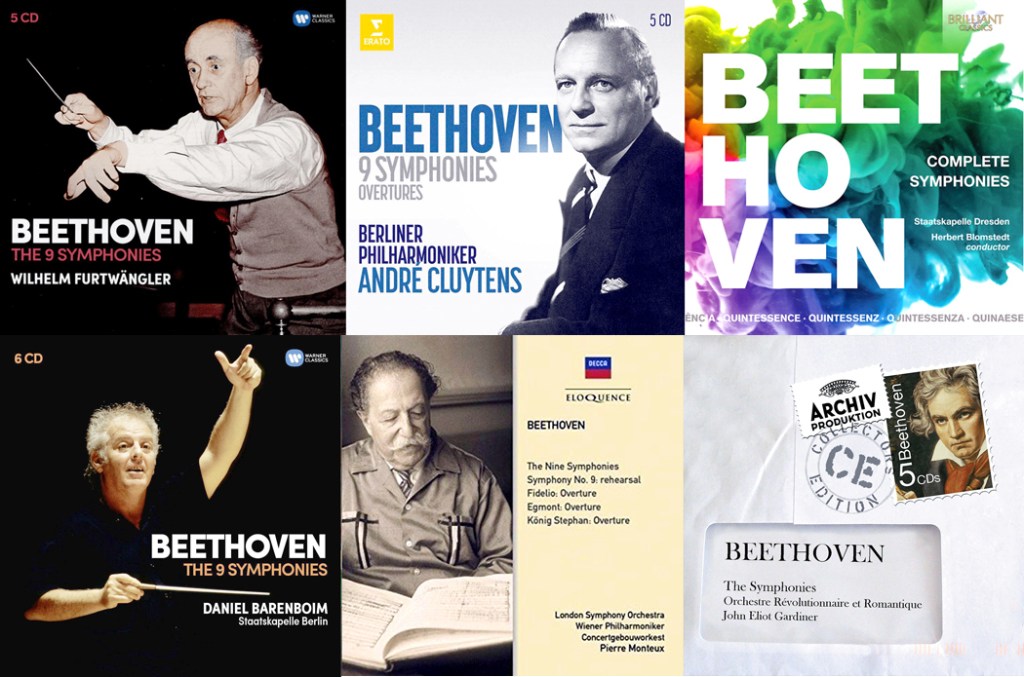

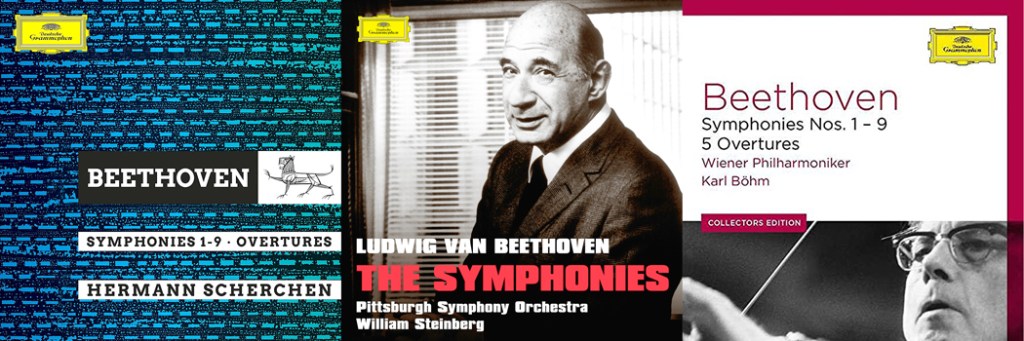

I currently possess 26 full sets of the Beethoven symphonies, ranging from the historical (Mengelberg) to the historically informed (Gardiner) and when I listen to them, yes, I have my favorites, and could (if paid) produce a list ranking the top 10. But they would merely be the ones I, personally, like the best. If I am fair, I have to say that pretty much all of them deliver the goods.

(The only two exceptions are a set I no longer own — the Roger Norrington set — which is pure ordure in a garden of blooms. I threw it away; and the recordings of Sergiu Celibidache, which are perverse, and which I keep, mostly as a party record, to play for friends as a joke).

But I can put on a Pastoral by Josef Krips, or an Eroica by George Szell, and I am hearing Beethoven. The wayward rubatos of Furtwangler or the strict disco beat of John Eliot Gardiner both bring me worthy Beethovens.

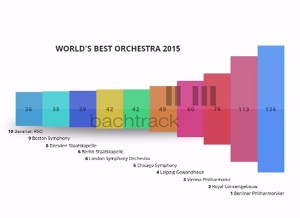

The fact is, while you may absolutely detest the oozy legato strings of Herbert von Karajan, or the granitic tempos of Otto Klemperer, they are all excellent performances, and if you only owned one set (heaven forfend) you could be completely satisfied. Monteux, Chailly, Zinman, Bernstein, Leinsdorf, MTT, Harnoncourt — any of them — all give excellent, if different performances of the symphonies. You can have your favorite, but you have to admit, none of them is negligible, and all have something to say.

It is like having to choose between Rembrandt and Vermeer. Is one of the better? Stupid question. Is Titian a better painter than Monet? What is the greatest novel? War and Peace? Don Quixote? Madame Bovary? Ulysses? Á la recherche du temps perdu? C’mon, man, rankings are idiotic.

As an art critic for 25 years, I got to visit hundreds of art shows, from major international exhibits in New York, Chicago or LA, down to children’s art in grade school, and it is not that I am saying it was all wonderful — some art is certainly more accomplished than other art — but that universal approbation is no indicator of value.

Yes, Jeff Koons or Kara Walker may be the names on trendy lips, and we may think of them as among the leading artists of our times, but I saw work by local artists that, given the right breaks, could be just as famous and lauded. There are tons of artists — painters, actors, musicians — just as good as some of our most praised, but who either lacked the vaulting ambition for publicity, or never had the dumb luck to have been discovered by some influential critic.

Is there any reason that David Hockney is ubiquitous and that Jim Waid is not? Waid is clearly as good a painter, and his canvases as original and distinctive, yet Hockney jet sets, and Waid paints in his studio in Tucson, Ariz. (I don’t mean to imply that Waid has no reputation — he does nationally — but nothing like the magazine-cover familiarity of Hockney). And I could find a dozen artists from any of the United States whose work would be as worthy.

Sports may seem easier to listify, as we can always quantify the ten highest batting averages for any season or for career, although any real baseball fan knows that batting average doesn’t tell the whole story. And while we might compile a list of the greatest pitchers of all time, and there might be some agreement on the names, ranking them from the best on down will depend on one’s team allegiance or the era in which you most closely watched the game. Walter Johnson on top? Nolan Ryan? Bob Gibson? Sandy Koufax? Mad Dog Greg Maddux? Again, at that level, it’s all just opinion.

Top 10 presidents? Again, there is cream at the top, and some sludge sinking to the bottom — and a fair consensus for top and bottom, even if the vast middle ground is murky, but how do we rank them all? Was Polk a better president than Hayes? Does Grover Cleveland get two spots on the list? Or just one, combined?

List making is addicting, perhaps, but it is also empty calories. When I go scrounging through YouTube offerings, I am besieged by lists. They are click-bait and I have long ago learned to ignore them. Who was the worst mass-murdering tyrant in history? Who was the best defensive player in basketball? What are the Harry Potter books listed from best to worst? I don’t care. If you have something substantive to say about Hitler or Genghis Khan, about Bill Russell, or about the philosopher’s stone, then write something meaningful. Lists are an easy way to avoid engaging with actual thought.

And I’ve made a list of them…