When I was a boy, in the 1950s, in an era not far removed from the Second World War, when Army surplus stores were common and provided much of the hardware we kids used for our play — helmet liners, canteens, mess kits, ammo boxes — we divided up into “good guys” and “bad guys,” just as we divided into cowboys and Indians. The good guys were American, of course, and the villains were “Japs” and Nazis. Usually Nazis.

But as boys, we pronounced the word as if it were pure American English: “Nah-zees,” where the first syllable had the “A” sound in “nap.” Nazees. It was only years later that we realized that in German, the word was closer to “Not-sees.”

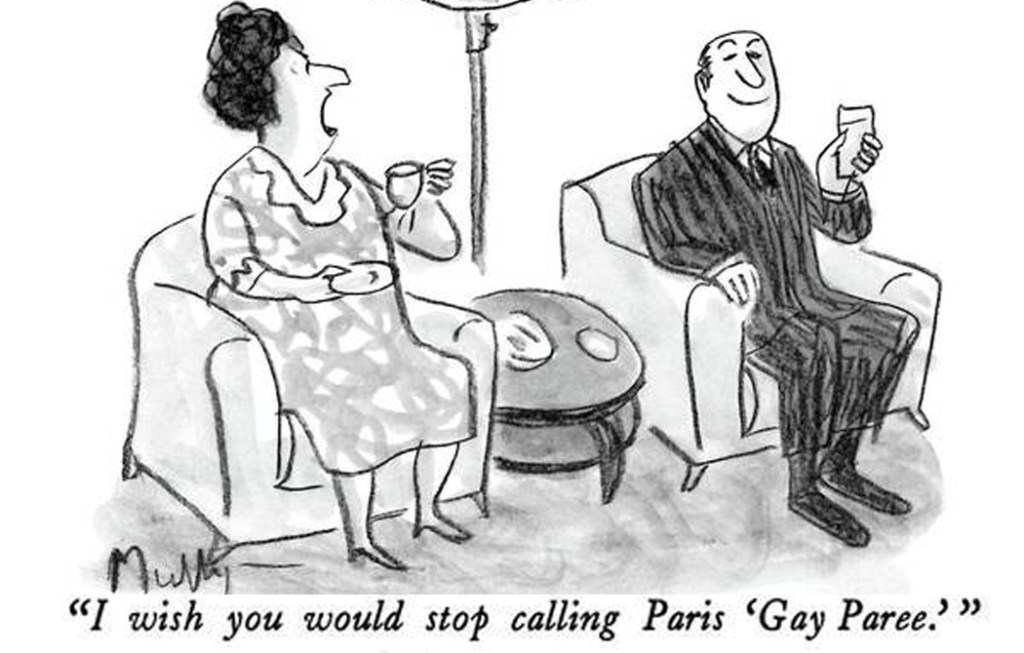

And ever since, I have been fascinated by the way foreign words and names tend to get naturalized into something familiar on the tongue. We say “Paris,” and not “Paree.” “Moscow,” not “Muskva.” Cuba as “Kew-buh,” not “Koo-ba.”

I came across a piece recently by linguist Geoff Lindsey about this tendency, and the range of possibilities, and how the British and Americans tend to vary in the attempt. And also, how the Americans have lately tended to attempt to “un-nativize” foreign words and names — to varying degrees of success. Something we might call “collateral decolonization.”

Think of the automobile called the Jaguar. The English have subsumed the name into the habits of British English and say “Jag-you-are.” (Sounds a little like Yoda-speak.) The Americans go halfway and say “Jag-war.” The word originates in a native Brazilian language, where it was pronounced “Yag-wara” (“iaguara.”) The initial “I” gets transliterated by the conquering Portuguese as a “J,” and thereafter acquires the “dz” sound.

The Brits give us “Nick-uh-RAG-yoo-ah,” also, while in the U.S., we still mostly say “Nick-uh-ROG-wa.” Over the pond, the Brits put the “past” in “pasta,” where we soften the “A” into something closer to “pahstuh.”

Which is the better solution? You pays your money and takes your choice. Sometimes one is better, sometimes the other. In America, now richly influenced by Spanish, we tend to indiscriminately use the Latino vowel sounds we know from the Spanish we pick up in restaurants, even if we’re trying to say French or German words. Many Spanish words have become common in the U.S., and so we tend to sound them out better than Londoners, who shove a “tack” in “taco,” and a “dill” in “quesadilla.”

One has to remember how Lord Byron once rhymed the Guadalquivir river in the lines: “Don Juan’s parents lived beside the river,/ A noble stream, and call’d the Guadalquivir.” And, of course “Don Juan” was “Don Joo-un,” which he rhymes with “true one.”

But it isn’t only Spanish. The U.K. also has a hard time with French — or perhaps not a hard time so much as a natural and historical antipathy to all things Gallic — and can truly butcher French words. Americans don’t have an easier time with French vowels, either, but we tend to put the accent on the final syllables of French borrowings, to sound more French, such as “garage” and “massage,” while the English say “GAR-idge” and “MASS-ahdge.” They do the same to “salon” and “cafe,” with first syllable emphasis.

It isn’t just English, of course. Other languages face similar problems, when sounds that are common in one language are absent in the other. There is no “H” in Russian, for instance, and so they transliterate “Harry Potter” into a Cyrillic “Gary Potter” (or “Гарри Поттер”). “Ze French” don’t do the “TH” sound, so they have a monster of a time with English. There is no good “J” sound in Norwegian. I remember visiting the port of Kristiansand with my distant relative Anders Vehus and looking up at the bow of a docked ship named “Southern Jester,” and trying over and over to get him to pronounce it and getting “So-tern Yestair.” I would mouth the “J” and he would repeat “Y.” Over and over. (I had long given up on the “TH.”)

And so, Puerto Ricans tend to say “New Jork.” Familiar sounds planted in unfamiliar soil. Many American towns and cities were named after foreign places, and been given new pronunciations. Sometimes it is only the local population that knows that Calais in Maine is “Ka-less” or that Newark, which in New Jersey is mostly pronounced “Nerk,” but in Delaware is “New-Ark.”

There are a whole host of examples: Lima, Ohio, is “Lie-ma;” Pierre, S.D., is “Peer;” Cairo, Ill., is “Kayro” just like the syrup; in Illinois and Kentucky, they say “Athens” like the letter “A-thins;” Milan, Tenn., is “My-lin;” Versailles, Ky., and Ill., are “Ver-Sayles;” New Madrid, Mo., is “New MAD-drid.” There are others.

I particularly marvel at Pompeii, Mich., which is said as “Pom-pay-eye,” to account for the double letter “I” at the end. And, of course what is Houston in Texas, is a street in Manhattan called “How-ston.” And although it seems to be changing, old-timers Down East know that Mt. Desert Isle is “Mount Dessert.”

Most such locales were named in previous centuries, when people didn’t get around as much and awareness of different languages was scant. And so, in a more aware world, many Americans are trying to be more sensitive to names in other cultures. On the whole, this is undoubtedly a good thing.

But there are words and names that are buried deep in language history that are no longer foreign words, but naturalized English versions of them. We are not likely to start calling the French capital “Paree.” It’s not a French word. “Paris” is established English. Same with “Germany” rather than “Deutschland.” (Or “Alemania” in Spanish or “Niemcy” in Polish, “Tedesco” in Italian, or “Tyskland” in Swedish.

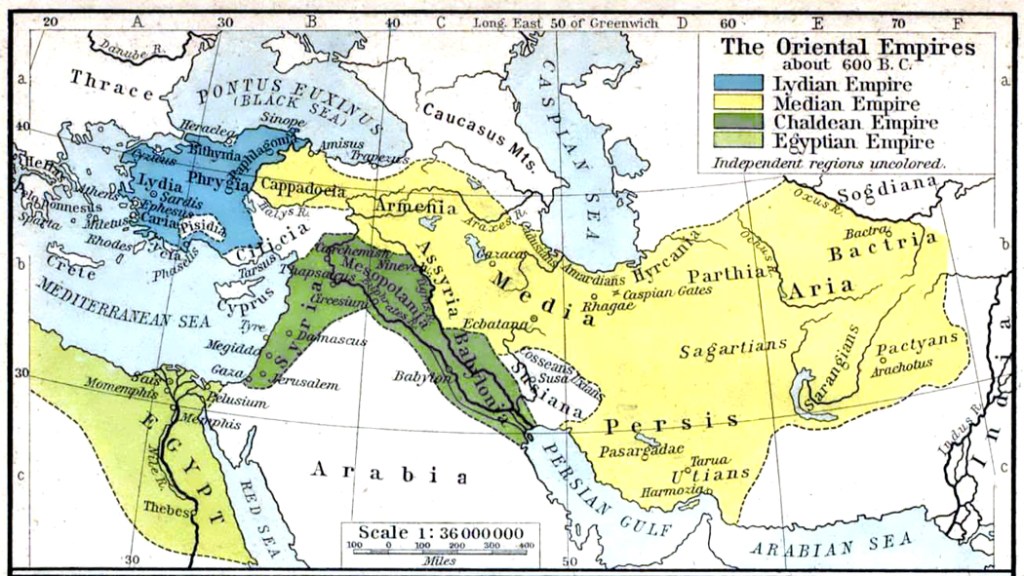

In English, we have hordes of such legacy names, unused in their native lands. Exonyms (what we call them) and endonyms (what they call themselves) are a common feature around the world. In English a selection includes: China for Zhōngguó; Egypt for Masr; we say “Japan,” they say “Nihon;” South Korea is Hanguk; Norway is Norge to the Norsk; Russia is Rossiya to Ivan; Spain is España; and many others. Among cities: Vienna is Wien; Copenhagen is København; Bangkok is Krung Thep; Florence is Firenze; Cologne is Köln; And in English, Roma will always be Rome.

There have been changes, or attempts at change. Some have taken, others haven’t. We are asked to use Myanmar instead of Burma; India has recently attempted to be called Bharat; we used to habitually call Ukraine, “the Ukraine,” just as Argentina used to be “the Argentine” — and still is in most Spanish usages — “l’Argentina”; there was a time when Cambodia asked us to call it Kampuchea, which it still is to itself; What was Kiev is now Kyiv; Mumbai was once Bombay in English.

China is a special problem, being a toned language and many regional dialects. Over time, what we now call Beijing has been “Peking,” Pekin,” “Peiping,” “Pei-p’ing,” “Beiping,” and “Pequim.” All various attempts at using the Roman alphabet for sounds that just don’t exist in Romance or Germanic languages. The Chinese government declared, in 1958, that the then-new Pinyin system of should be official, and since diplomatic normalization between mainland China and the U.S., in 1979, it has become almost universally adopted. And so, now, we all write “Beijing.” However, we still order Peking duck at the restaurant.

Sometimes, this sensitivity to other languages can go overboard, and we fix things that need no fixing. Called “hyperforeignism,” this is trying to sound more French than the French. We sometimes do it jokingly, like when we shop at “Tar-zhay.” But sometimes it slips by un-ironically, as when we say “Vishy-swa” when we mean “Vichyssoise. Taking that final “S” off the end sounds more French — I guess.

It can be quite comic. Striking a “coup de grâce” should end with an “S” sound. But if we want to sound sophisticated, we say “Koo-de-grah,” which, of course, actually means, in French (coup de gras) “Blow the fat.”

I once heard a college radio announcer tell us we were about to hear a symphony by “Gus-TAV Mah-LAY.” And sometimes you hear Hector “Bairly-O.” Overcorrection.

Because many Spanish words include the letter “Ñ,” sometimes Americans will add that tilde where one doesn’t belong, as saying the chile called the Habanero as if it were “Hab-an-nyair-o.” Sometimes we also add the tilde to “empanada” or conversely, take it away from “jalapeño.” (The British pronunciation rather combines both tendencies: “hala-peen-yo.”)

The desire to be “correct” can make you seem either pretentious or, perhaps a bit dippy. I remember watching my local newscaster, back in 1990, with the electoral overthrow of the Sandanistas, give us the news from “Nee-ha-RAH-wa,” which jumped uncomfortably out of his mouth in the middle of otherwise normal English wordage, with even a tiny hesitation as he shifted his mouth from English to his version of Spanish, and back. It was clear he was showing off, but it seemed quite offputting. Remember, “Nicaragua” is an English word, with a long habitation in our tongue.

It is a cultural battle, fought over centuries, between not wanting to sound like a rube, on one hand, nor to come across as too “Frenchified” and trying to be something you’re not. The line between the two extremes is constantly shifting, and has for centuries, and where it winds up in, say, 50 years, is impossible to predict. Language is fluid.