When you have ideas where your ears should be, you can be such a self-righteous moron. My Tchaikovsky problem is a case in point. I wasted years not listening to his music. What I thought closed my ears to what I might hear.

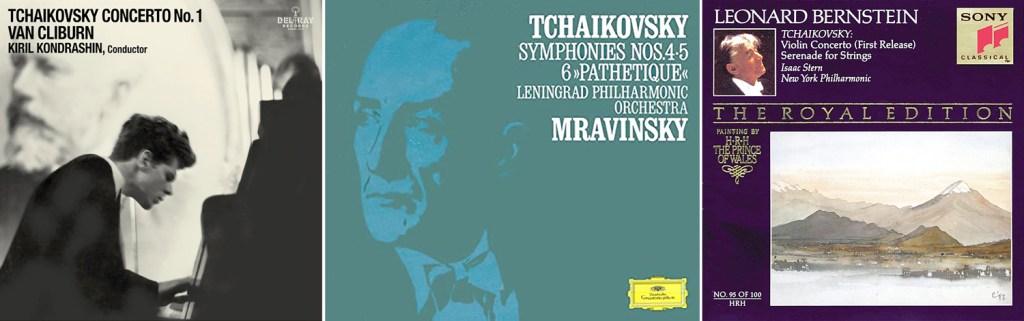

When I was a boy, longer ago than even your parents can remember, the music of Tchaikovsky was easy to love — all those sweeping tunes and swelling fiddles. His music was, in that antediluvian age, pretty well ubiquitous. Concert halls played his symphonies, pianists conquered the Soviet Union playing his piano concerto, and supermarkets offered LP specials for 49 cents with grocery purchases. And that is where I was first exposed to the Nutcracker Suite, played by an anonymous orchestra and conductor (Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite was on the “B” side).

My parents bought successive volumes from the supermarket and I became exposed to “The World’s Greatest Music,” including Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, the Brahms Second, the Sorcerer’s Apprentice and all of those now-familiar war horses a friend of mine used to call “The Loud Classics.”

A few years on, as puberty hit, it was music like Tchaikovsky’s that spoke to me, with its pile-driven emotional excess and immediacy. My insides swelled with powerful feelings. That sort of “heart-on-sleeve” thrum speaks to those newly activated hormones.

But then, unfortunately, I became smarter, learned more, read what critics had written. I discovered that such music was trivial, shallow, showy and unserious and learned how wrong I had been. My taste turned to Beethoven’s late quartets and Bach’s unaccompanied violin works. That was serious music.

This is something that happens to many of us when we are becoming adults and presume to take on more grown-up tastes, pretending to understand more than we actually can. Ideas about the music supersedes what we actually hear.

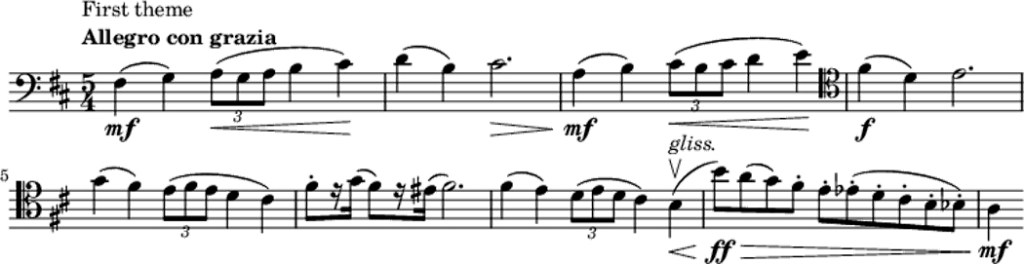

And so, for the next 40 years or so, I disdained listening to much Tchaikovsky. Occasionally I would spin the Pathetique on the record player. It, after all, had a second movement in 5/4 time. Like Dave Brubeck.

Looking back, I realize that the musical culture was traveling much the same route as I was taking. Music that had been pilloried for being too “modern” and “dissonant” became more mainstream. One could hear Bartok or Stravinsky in the concert halls, played alongside Beethoven and Sibelius. And musicians and conductors, grown up in the same era as I did, shared much of my taste. Tchaikovsky slowly became out of fashion. Astringent drowned out lush.

It was still played, of course, but less frequently, and by orchestras and conductors more simpatico with Modernist esthetics than the tired old Romanticism. Stravinsky had stated, in no uncertain terms “Music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all.” And Toscanini has said Beethoven’s Eroica was not about heroism, but about “E-flat.” (Neither man actually believed their own words, and their music and music-making prove that, but their words proved highly influential).

Toscanini also said, “Tradition is only the last bad performance.” But tradition is the very heart of any classical music — music handed down from one generation of masters to a younger generation. Whether it is Indian classical music, Japanese Noh flute playing, or Pablo Casals teaching Bernard Greenhouse (of the Beaux Arts Trio) and Greenhouse teaching Paul Katz, onetime cellist of the Cleveland Quartet) it is tradition that defines it.

Orchestras and conductors who had learned their art before the 20th century and continued the traditions up through, perhaps 1970 or so, had the music in their old bones, understood how it was meant to go, and how the musical arguments played out in the notes. But the older musicians died out and the younger generation taking charge had a more “objective” view of the music. A tradition was dying.

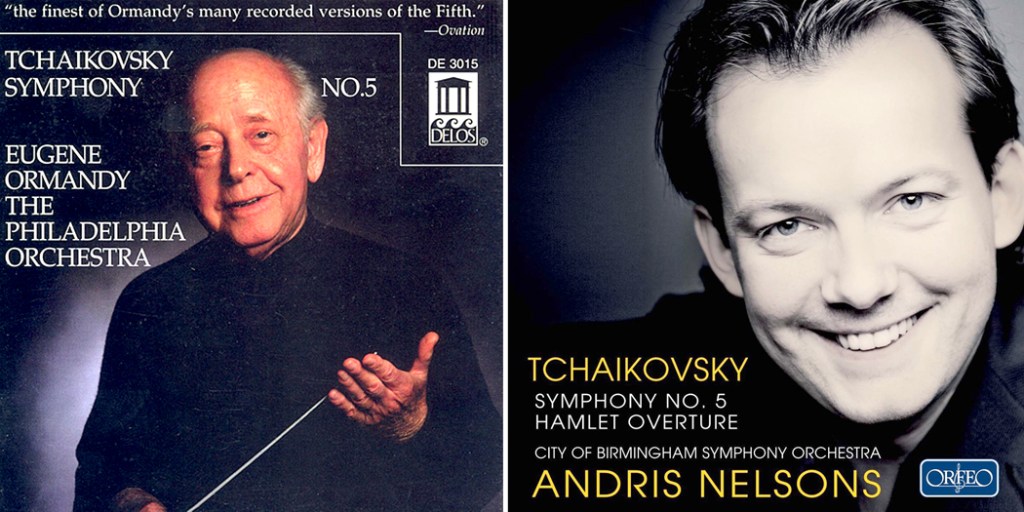

You can hear this by comparing any Tchaikovsky symphony recorded by Eugene Ormandy (1899-1985) or Yevgeny Mravinsky (1903-1988) with the same performed by Andris Nelsons (b. 1978) or Vladimir Jurowski (b. 1972). The younger players play the notes clearly and cleanly, even with excellent musicianship, but notes and music are different things. The younger generation grew up with Stravinsky or Prokofiev and had no problem with their complex scores. It was a shift in sensibilities. Younger musicians can breeze through Le Sacre du Printemps perfectly, while many old recordings show esteemed conductors fumbling through, missing accents and here and there. It’s a new tradition. (And I’m not even talking about “historically informed performance practice.”)

But in the 19th century music, the older conductors knew much the younger generation had no grasp of. They knew how the music “went.” What it was saying.

The true divide between the old and new were the World Wars and millions of dead. And especially after the genocide of the Second World War, it was no longer possible to believe in such old ideas as nobility or heroism. And music about such things no longer rang true. Listen to the version of Franz Liszt’s Les Preludes performed by Kurt Masur and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, from 1978 and you hear all the notes, and certainly there is excitement. But listen then to the 1929 performance by the Amsterdam Concertgebouw and Willem Mengelberg, and you hear music that believes what it is saying. There is an earnestness to it, a fervor, that feels second-hand in the Masur recording. The difference between a hero and an actor playing a hero.

And so, I and the generations that grew up with me and after me no longer had the stomach to hear such “universal” emotions as Tchaikovsky tried to evoke in his music. Nothing universal could be trusted anymore, and the grand statements of fate and tradition were dumped.

I remember when teaching, a student pushed back on something I had said. “It’s all relative,” she said. “Nothing is true. It is your truth or my truth, but nothing is universally true.” It was a common belief for her generation. And given the “truths” espoused by various institutions that were shown to be mere self-serving hypocrisy after Watergate, after “I did not have sex with that woman,” and most of all, after Auschwitz, it was hard to fault her.

But I replied: “There is one truth that is universal. You will die. I will die. All living things will die.” That, I said, is the starting point for all art. After that, we look for anything else that we may make art from. Second truth follows from the first: The people you love will die, and many of those will die before you and you will suffer loss. How do you react to that loss? Yes, some Victorian pieties seem like sentimental claptrap to us now, but the impulse behind them is very real, and we can react to that reality.

And so, when I hear Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique, I feel deeply in my psyche the sense of death and loss inherent in the harmonies and melodies, and I am moved. Deeply moved. If the stylistic idiosyncrasies of his age are not ours, the underlying emotions are.

It is incumbent upon us, as listeners (and readers, and theater audiences) not to be deaf to the content of art. Yes, some music is meant only as divertissement, as Mozart serenades or Schubert ländler, but the more ambitious pieces — symphonies, operas, even ballets — are responses to the larger questions. Not only death or loss, but the subsequent propositions built from those original two: What is happiness, what is narrative, what is rhythm and physical movement and how does it all reflect the experience of being alive?

If you listen to Tchaikovsky’s music with ears instead of ideas, you hear not only emotions both bright and dark, but extraordinary melody and harmony, often rather advanced for its time, and unparalleled brilliance of orchestration.

Even so minor a piece as his Nutcracker ballet is built from absolute crystal gems of sound combinations. Pure genius.

The disdain so many now feel for the music of Tchaikovsky, or, for that matter, Rachmaninoff, or others of their era, is, as far as I am concerned, unearned, and merely an expression of ignorance. One should never cut oneself off from such delight, pleasure, and the emotions evoked. One should never close off one’s ears to music, or let ideas about the music take charge.